Words

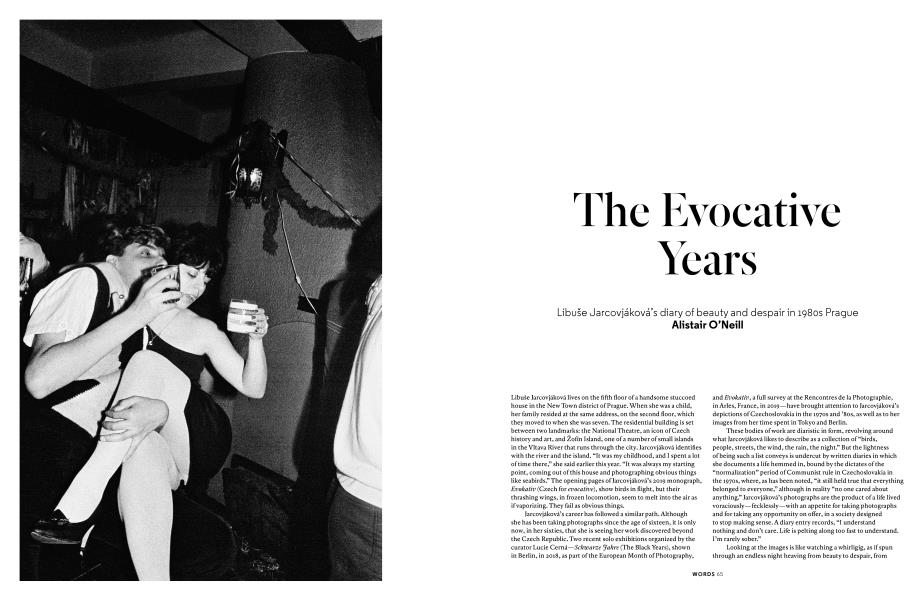

The Evocative Years

Libuše Jarcovjáková's diary of beauty and despair in 1980s Prague

Summer 2020 Alistair O’NeillLibuse Jarcovjáková lives on the fifth floor of a handsome stuccoed house in the New Town district of Prague. When she was a child, her family resided at the same address, on the second floor, which they moved to when she was seven. The residential building is set between two landmarks: the National Theatre, an icon of Czech history and art, and Žofín Island, one of a number of small islands in the Vltava River that runs through the city. Jarcovjakova identifies with the river and the island. “It was my childhood, and I spent a lot of time there,” she said earlier this year. “It was always my starting point, coming out of this house and photographing obvious things like seabirds.” The opening pages of Jarcovjakova’s 2019 monograph, Evokativ (Czech for evocative), show birds in flight, but their thrashing wings, in frozen locomotion, seem to melt into the air as if vaporizing. They fail as obvious things.

Jarcovjakova’s career has followed a similar path. Although she has been taking photographs since the age of sixteen, it is only now, in her sixties, that she is seeing her work discovered beyond the Czech Republic. Two recent solo exhibitions organized by the curator Lucie Cerna—Schwarze Jahre (The Black Years), shown in Berlin, in 2018, as part of the European Month of Photography, and Evokativ, a full survey at the Rencontres de la Photographic, in Arles, France, in 2019—have brought attention to Jarcovjakova’s depictions of Czechoslovakia in the 1970s and ’80s, as well as to her images from her time spent in Tokyo and Berlin.

These bodies of work are diaristic in form, revolving around what Jarcovjakova likes to describe as a collection of “birds, people, streets, the wind, the rain, the night.” But the lightness of being such a list conveys is undercut by written diaries in which she documents a life hemmed in, bound by the dictates of the “normalization” period of Communist rule in Czechoslovakia in the 1970s, where, as has been noted, “it still held true that everything belonged to everyone,” although in reality “no one cared about anything.” Jarcovjakova’s photographs are the product of a life lived voraciously—fecklessly—with an appetite for taking photographs and for taking any opportunity on offer, in a society designed to stop making sense. A diary entry records, “I understand nothing and don’t care. Life is pelting along too fast to understand. I’m rarely sober.”

Looking at the images is like watching a whirligig, as if spun through an endless night heaving from beauty to despair, from hedonism to dread. Diary entries for August 1980 read like a stream of consciousness:

WORDS

Warm developer in the bathroom, boiling water for tea, coffee, cigarette burning in an ashtray, and a second on the clock running and running. From 14:00 to 16:00 I want to enlarge the remaining photos of Homo Faber.

Sex, why so much? When I am with Franta, two or three times a day, do Mirek about once every fortnight and special occasions plus more, that means practically daily.

Grub. It is quantity, quantity, quantity.

The pint of wine I have in my head is a big hindrance to my sleep and also to making me feel better. Sunday. Binge at Mirek with a proper morning finish, Monday from midday with Standa until after midnight left home. Yesterday hangover, heart attacks.

Jarcovjakova fashioned for herself a world where photographs were a measure for a life without self-control. She was drawn to distraction, and found that taking photographs involved absenting herself from reality. Much of the work is born out of the interplay between being focused and being unfocused, as Jarcovjakova explains:

I am mostly observing something I feel, and I am really very happy to be with people but I am always a little bit absent.

I am there but with some small distance as I am not trying to describe the situation. I wrote in my diary in Tokyo that I am trying to document the world without doing documentary photography, without describing it. Somehow I atomize it.

The photographs have a loose, snapshot-like style, unafraid of harsh flash lighting, eyes half-closed, or heads cut off. But the longer you look, the more formal they become, with a sensitivity to surface texture, the shapes bodies can make, and the density of monochrome tones. Jarcovjakova regards a photograph not as a representation of a moment, but rather as a trace of something behind or above it. She has said that bringing an image into the world provides the “ability to find myself, where I am, who I am— to give the situation some sense.”

Jarcovjakova’s parents fostered her desire to train as a photographer. The family mixed in artist circles, and her father was a member of the Trasa 58 group. After high school, Jarcovjakova enrolled in a graphics course with the intention of going to university, but the Communist screening process identified her parents as “politically undesirable” rather than working-class— a label that barred her from continuing her studies. After being refused admission to the Film and TV School of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague, she decided to make her own way—

“to be accepted as a worker”—in a country that placed symbolic value on optimized physical labor in the workplace.

At the age of nineteen, Jarcovjakova entered a printing factory, working three shifts back-to-back in an atmosphere of noxious fumes until six in the morning, then drinking with her fellow workers in the downtime before the presses restarted at 10 AM.

The “very strange society” she found herself in made an absurdity of productivity; intoxication was as mechanical as the ink plates pressed into paper. Jarcovjakova recounts that in three weeks she was “completely dissolved.” It was only after a year of employment that she started to take photographs using a Pentacon Six mediumformat camera in a workplace she now found “very beautiful and visual.” The project was halted when a Communist Party representative visiting the factory saw Jarcovjakova taking pictures.

Still, it was a formative experience: “It was the first time I was able to approach people to take photographs of them without fear, and secondly, I saw where I was,” she says.

In 1977, on her fourth attempt, Jarcovjakova was finally admitted to the Academy of Performing Arts. By then, she was twenty-five among eighteen-year-olds, an outsider “who rarely came in before four in the morning.” Her photographs didn’t fit with the prevailing European documentary style taught, and she was discouraged from showing her work. However, she studied the history of photography with Vladimir Birgus, an influential professor in Prague, and through her father’s network she encountered the writer and curator Anna Farova, who had been fired from the academy in 1977 for signing the dissident public petition known as Charter 77. Visiting her privately, Jarcovjakova was allowed access to Farova’s personal library that held books unavailable or forbidden in their country. Here, she was introduced to members of the New York School of photography, such as Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand, Robert Frank, and Richard Avedon, as well as to Josef Sudek’s surviving archive, which Farova was engaged in preserving and cataloging.

Jarcovjáková regards a photograph not as a representation of a moment, but rather as a trace of something behind or above it.

Jarcovjakova began to take photographs of communities in Prague, finding herself drawn to visual difference and marginal status. She devised a three-shift schedule, always with “my camera around my neck”: in the morning, she taught Vietnamese and Cuban children the Czech language; in the afternoon, she visited Romani gypsies resettled by an integration program in residential apartments; and in the evening, she headed to the clandestine gay nightclub T-Club. As she recalls, she experienced “three worlds in one city, and everywhere I felt at home.” Yet the photographic work Jarcovjakova amassed differs from the documentary tradition, even though her subjects might not. There was “no opportunity to publish,” she says, “so it was very spontaneous and natural. It was a visual adventure—but I was not a researcher.”

Because photographs taken in a space like the T-Club could be used by the authorities as evidence against gay men and women, Jarcovjáková had to build trust with the patrons, brokered by friendships and relationships with the male and female clientele.

She decided “to use flash light in order to be seen. For me it was important, that I am taking photographs and I am taking them with your permission.” In exchange for being photographed, she would return the following night to gift a print to each of her subjects. (Jarcovjakova believes there are numerous vintage prints out there, still unaccounted for.) Her working records of this productive period are contact prints on document paper, a cheap photographic paper chiefly used at the time for reproducing samizdat—facsimiles of books banned by the authorities. This material bestows her images with an illicit quality that aligns Jarcovjáková’s work with the dissident ideal of freethinking: a setting down of frames of a life lived in poetic defiance.

While these projects offered a diversion to Jarcovjáková’s existence, and even though Farova included her photographs in two important exhibitions in Czechoslovakia, 9 x 9, in Plasy, in 1981, and 37—fotogmfu na Chmelnici (37 photographers at Chmelnici) in 1989, Jarcovjakova grew disillusioned with the containment of her life in Prague. She managed to broker trips to Japan working as a commercial photographer before she immigrated to Berlin in 1985, secured by a sham marriage to a man she soon lost sight of. When she arrived at Yokohama Port on her first visit to Japan, an official held aloft her passport photograph to inform her that the woman who had arranged her visit had been detained in a psychiatric hospital and had spent the money Jarcovjakova had sent in advance. The commercial fashion work she eventually secured in Tokyo, instigated by the accessories and fashion designer Katsuyuki Yoshida, often placed her in situations beyond her expertise. Jarcovjakova remembers arriving at a TV studio to do a fashion shoot with a “terrible Olympus camera with one lens,” where “the hairdressers and makeup artists had better cameras than I did.” All that remains in print form from this period is a beguiling set of portraits of Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garfons taken in 1986.

Because photographs taken in a space like the T-Club could be used as evidence against gay men and women, Jarcovjakova had to build trust with the patrons.

Her self-portraits are studies in isolation that speak of a morning that never comes, far from the term selfie that is now used to describe them.

In Berlin, unable to draw upon social benefits because she couldn’t speak adequate German, Jarcovjakova cleaned cinemas to earn a living. She found herself increasingly alienated and withdrawn. The fear she experienced prompted her to turn the camera on herself, looking for “a structure.” “I was definitely alone,” Jarcovjakova says. “I was thirty-two, and every experience from the past was useless.” Her self-portraits are studies in isolation that speak of a morning that never comes, far from the term selfie that is now used to describe them. In 1990, she formally returned to Prague, one year after the Velvet Revolution, which led to the fall of the Communist regime and, in 1993, to the establishment of the Czech Republic and Slovakia as two countries.

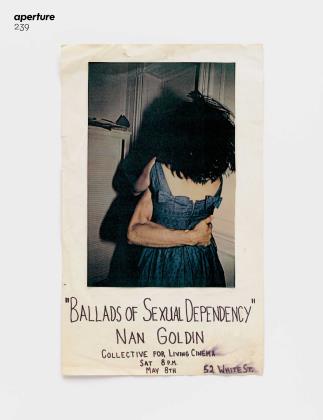

But Jarcovjakova resists the weight of history. While Czechoslovakia undoubtedly suffered some of the most extreme oppression and privation of any country under Communism, her photographs speak of lived experience in a way that differs from the historical record of Czech photography, an approach to representing the past that Jarcovjakova actively avoids. She recounts, for example, speaking to a Czech curator who advised her: “It is so important that you show the heaviness and the darkness.” Jarcovjakova’s decision to work with Cerna, who is from a younger generation that experienced the end of Communist rule only as children, is fundamental to an intended reading of the photographs. “Her work is not a document of an age,” Cerna writes, “it is an authentic record of the life of a photographer who experienced everything she shot.” It’s a viewpoint that connects Jarcovjakova’s work to that of Nan Goldin, although she only came across The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1983-2008) in 2012, having failed to see I’ll Be Your Mirror, an exhibition of Goldin’s work, when it toured to Prague in 1999. What both photographers share is the transcendence of the personal through their visceral, irrepressible conveyance of the human condition under duress.

Jarcovjakova chose the title of the publication, Evokativ, because she thought the project “should evoke something from the past: it is not a story, it is not a movie, it is not a documentary, it is not a diary, it is all of them together.” It makes sense to think of her photographs as flashes out of the darkness, from a time distant from the here and now, like a memory of something seen for the first time. Yet the word evoke has a secondary meaning, arising from the Latin word evocare, which translates as “to call forth,” or “to conjure spirits.” What is so striking about her many subjects is that you can recognize in the photographs a sense of their absence, a sense of their temporary release from daily stark realities. As if by being physically captured in a photograph, they reveal their psychological state as being elsewhere. There’s an unbearable lightness produced from the provisional state of throwing off circumstance, a spectral sense of joy.

Jarcovjakova’s life has now come full circle, returning her to the river and island of her childhood, but not necessarily to the obvious. Zoffn Island has a curious history, as it is where Andre Breton announced Surrealism to Czechoslovakia in 1935 at the Manes Gallery. It’s a visual strain that runs through Jarcovjakova’s work: she identifies with a type of realism skewed by the unordinary. Standing on Zoffn Island, Breton described Prague as “one of those cities that electively pin down poetic thought, which is always more or less adrift in space.” Jarcovjakova spent time in this city herself adrift, ingraining the things she pinned down with a poetry around what was imbibed along the way. Her photographs are a testament to the doggedness of individual will in the face of no reason. Breton ended his talk by expressing how Prague “carefully incubates all the delights of the past for the imagination.” Jarcovjakova’s great talent as a photographer is that she has delivered the city’s strangest and saddest time to the imagination as a troubling fascination and delight.

Alistair O’Neill is Professor of Fashion History and Theory at Central Saint Martins, London.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Pictures

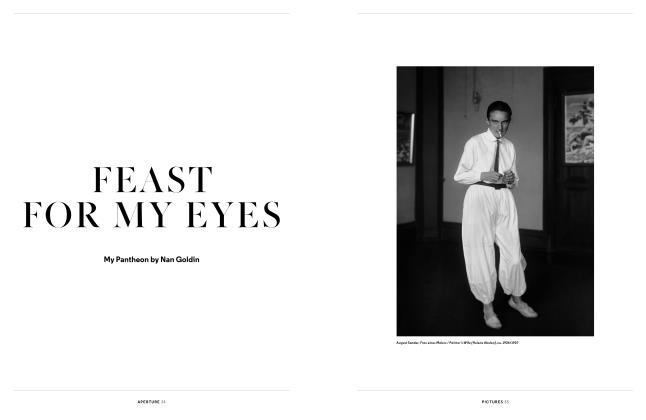

PicturesFeast For My Eyes

Summer 2020 By Nan Goldin -

Words

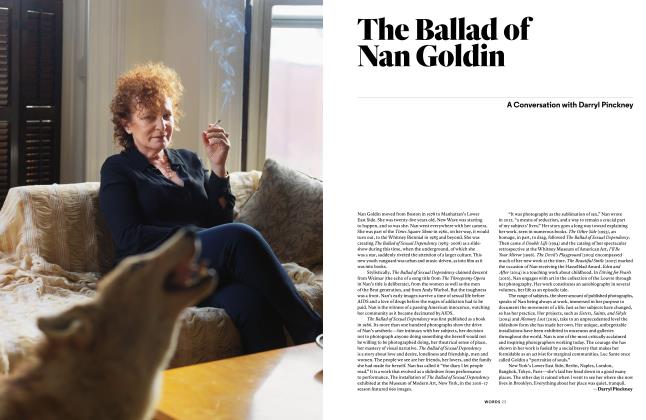

WordsThe Ballad Of Nan Goldin

Summer 2020 By Darryl Pinckney -

Pictures

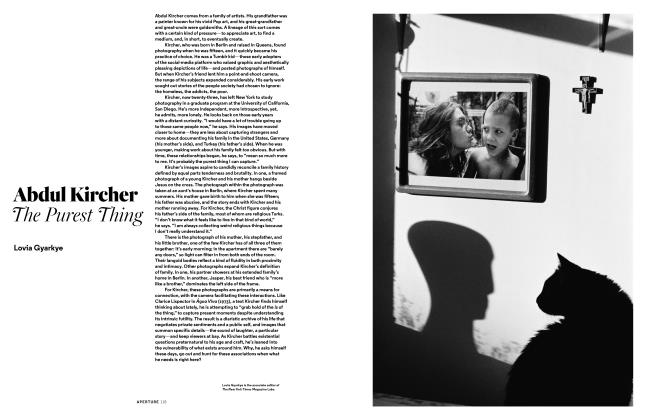

PicturesAbdul Kircher

Summer 2020 By Lovia Gyarkye -

Pictures

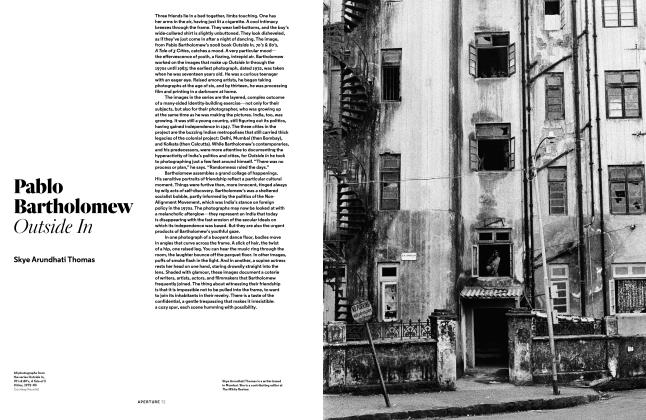

PicturesPablo Bartholomew

Summer 2020 By Skye Arundhati Thomas -

Pictures

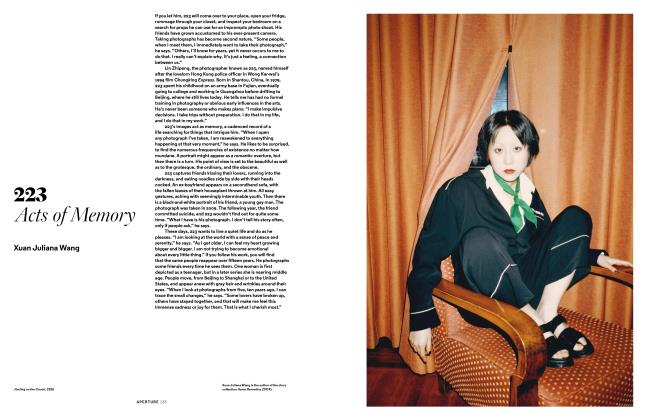

Pictures223

Summer 2020 By Xuan Juliana Wang -

Words

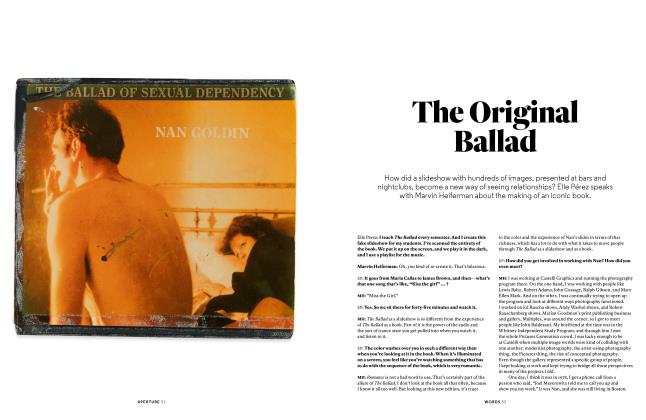

WordsThe Original Ballad

Summer 2020

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Alistair O’Neill

-

Words

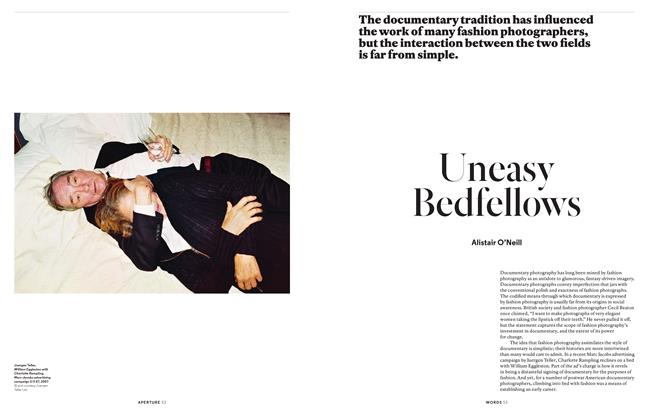

WordsUneasy Bedfellows

Fall 2014 By Alistair O’Neill -

Words

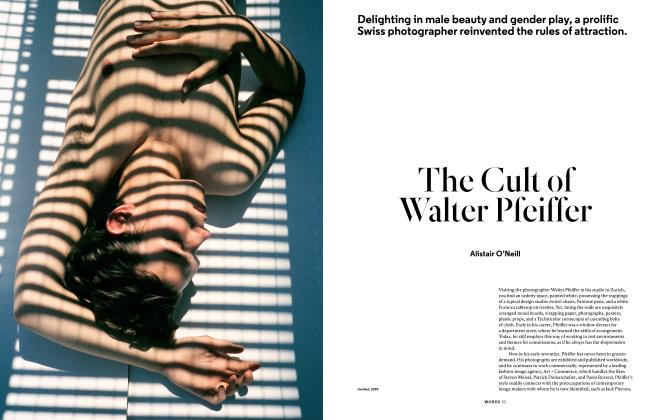

WordsThe Cult Of Walter Pfeiffer

Fall 2017 By Alistair O’Neill -

Redux

ReduxRediscovered Books And Writings

Fall 2018 By Alistair O’Neill -

Pictures

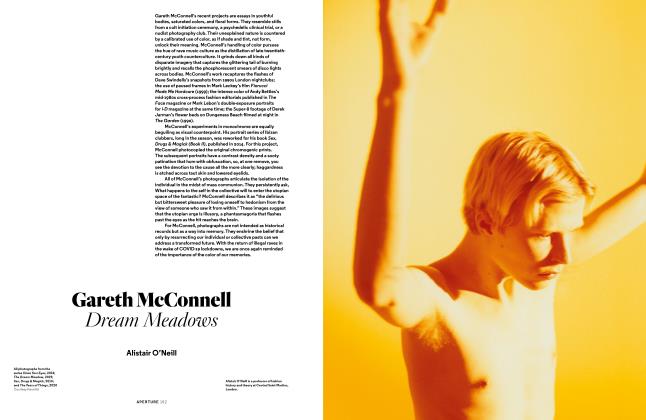

PicturesGareth McConnell

Winter 2020 By Alistair O’Neill -

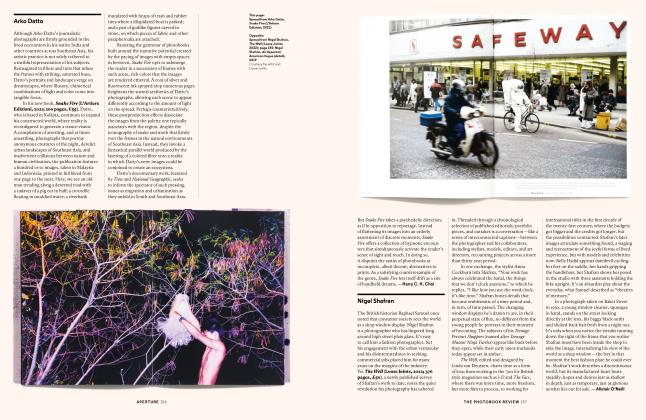

THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEW

THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEWNigel Shafran

FALL 2022 By Alistair O’Neill

Words

-

Words

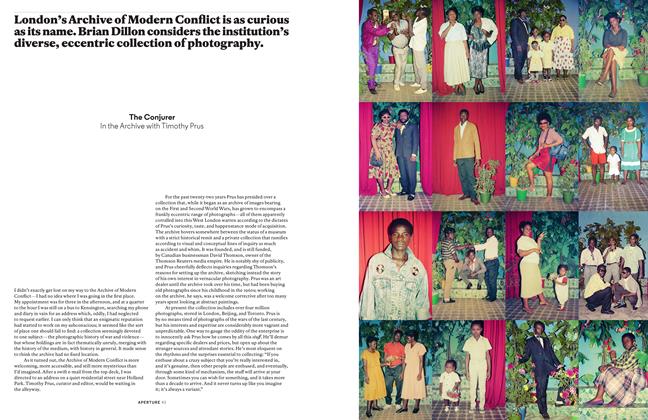

WordsThe Conjurer In The Archive With Timothy Prus

Winter 2013 By Brian Dillon -

Words

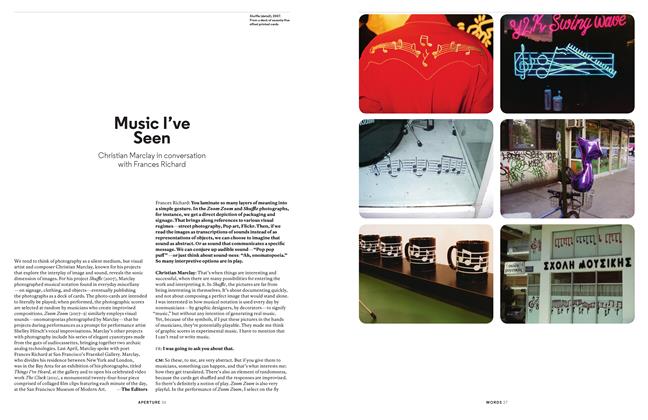

WordsMusic I've Seen

Fall 2013 By Frances Richard -

Words

WordsBeyond Binary

Winter 2016 By Julia Bryan-Wilson -

Essay

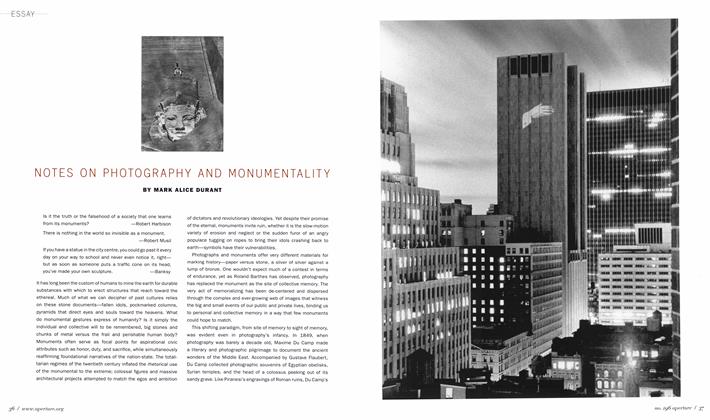

EssayNotes On Photography And Monumentality

Fall 2009 By Mark Alice Durant -

Words

WordsA Fold In Time

Summer 2020 By Olivia Laing -

Words

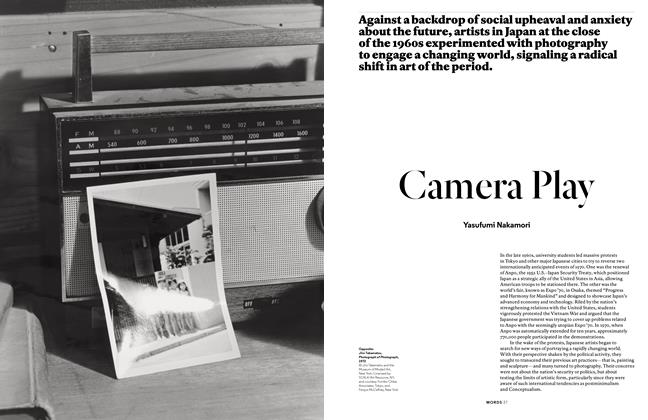

WordsCamera Play

Summer 2015 By Yasufumi Nakamori