MINOR WHITE

MANIFESTATIONS

IAN BOURLAND

PICTURES

In the summer of 1970, in Aperture, Minor White published “an experiment in fiction” called “The Tale of Peter Rasun Gould,” a series of brief vignettes recounting the narrator’s encounters with the seer-like titular character. Part reminiscence, part paean, the story outlines Gould’s idiosyncratic vision.

It was quintessential White—a once-aspiring poet who turned to photography in the years before World War II. He spent his career experimenting not just with photographs, but with how photographs change in relation to each other, to a viewer, and to a moment in one’s life. His “sequences” used versions of thematic pictures in shifting combinations, subtly altering their meanings. In the 1970 piece, which anticipates the work of W. G. Sebald and Teju Cole, White uses image and text to recount his experiences with the eponymous, guru-like figure, whose approach to photography is much like his own.

“The Tale of Peter Rasun Gould” is arguably the most elegant distillation of White’s views on photography as he entered the final years of a life dedicated to the medium. Fittingly, the writing is suffused with a far-reaching spirituality. The title’s three-part name refers to a kind of trinity, which is unsurprising—White was raised Catholic in Minnesota and grappled with both his faith and his sexuality for much of his early life. But this trinity is a subjective one too. The narrator speaks of his subject in symbolic terms: Peter as the perceiver of the outside world, the eye/I as camera; Gould as the voice within, the mind’s eye that helps one, in the parlance of White’s teacher Edward Weston, to “see photographically”; and that middle name, Rasun, with its implications of luminosity, as something stranger still—it seems to be the flash of what White calls “resonance,” that which makes a photograph more than mere document.

An encounter with resonance not only elevates a photograph to the rarefied terrain of art, but allows it, at the same time, to reveal “a splinter of divinity” in the world. In one section, the narrator reflects that the “days that Gould counted the ’happy accidents,’ he realized that neither Gould nor Peter had made the imagic photographs. They were gifts.” If the artist bridged the outer world with inner vision, there remained still a third element, one that could not be conjured, only quietly prepared for.

As suffused with mysticism as it is, the Gould story was of a piece with White’s continuously evolving vision of “creative photography.” He spelled out a version of this idea in an unpublished manuscript, from 1957, in which he recounts photographs that seemed to “find themselves.” Already a virtuoso technician and teacher, White acknowledges his own hard-won “oneness” with the medium, describing his senses as inseparable from the lens, negative, or final print on the wall. The camera, according to White, was an extension of his very self. Yet, he also concluded that technical mastery—which he shared with Weston, Dorothea Lange, and Ansel Adams— was insufficient. It merely prepared him to go out in search of the “happy accident.”

Like an ace driver, White knew how to press on recklessly while avoiding outright catastrophe; but he knew, too, howto cultivate chance, that ineffable thing just beyond our control. White concludes his essay by suggesting that his role as photographer was to work competently, “without bungling,” so as to create a membrane on which “an outside (or inside) power may leave its thumbprint.” Certainly, his work from this period, like 72 N. Union Street, Rochester (i960), is mundane in content but seems to radiate ethereal energy.

Such thinking was, of course, at odds with the photographic avant-garde of the day. As early as 1947, Weston accused White in a letter of seeing things in his work that were not there— a reference to the latter’s ongoing interest in the photograph as an index of invisible forces, psychoanalytic or otherwise. And in the years after White cofounded Aperture, in 1952, advanced photography was rapidly sorting itself into a variety of camps: the formalism of modernism, the lyricism of abstraction, the immediacy of the city street, or the dry wit of the conceptual.

For his part, White continued to plumb the depths of mysticism, as evidenced by his correspondence and personal diary.

In the 1950s, after he left California for good, White worked to integrate his study of the unconscious and performance theory with a universalist spiritualism tracing back to the European theosophical circles of an earlier era. In a letter from 1958 to Arnold Gassan, with whom he ran creative photography workshops, he parsed the differences in the teachings of the Russian mystic G. I. Gurdjieff and his student P. D. Ouspensky, and noted that he preferred the clarity he found in Zen Buddhism (as evident in his i960 sequence The Sound of One Hand Clapping). Over the winter of 1964, he corresponded with the Edwardian-era photographer Alvin Langdon Coburn, then living in Wales; they traded notes not about the medium, but on various occult traditions. White appeared to be an early subscriber to the new-age journals published amid the countercultural currents sweeping both sides of the Atlantic.

Such metaphysical seeking might have been a matter of personal necessity for White, who, after years of relative freedom in San Francisco and Portland, Oregon, endured a quasi-monastic life back East, one he described as a “banquet of frustration.”

In many ways, he felt peace—and sexual equanimity—only on periodic trips to the sublime canyon lands of the West. While many of his pictures of the West veered into abstraction, others were more direct, as in his portrait William LaRue, Capitol Reef National Park, Utah (1961). By contrast, the long winters of Rochester, New York, and Cambridge, Massachusetts, were something of a proving ground, marked by repression and sublimation. Such monastic discipline also yielded an epic body of work, registered in both words and countless exposures. In becoming one with the camera, attuned to the “happy accidents,” he found a way to let the light in.

White’s framework for photography was a project of solidarity rather than solipsism. If anything, there is a humility, a suppleness in White’s approach that defied the swaggering machismo of the era. From the outset, White was a tireless educator and organizer of photographic clubs. Ultimately, his photography was a humane one—not a document of the world or an expression of transient feeling. Instead, White’s spiritually infused practice, like Gould’s, was a way of drawing people together on both sides of the lens, of cultivating openness to possibility, of feeling a resonance with something bigger than any one of us.

Ian Bourland is assistant professor of art history at Georgetown University and the author of Bloodflowers: Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Photography, and the 1980s (2019).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

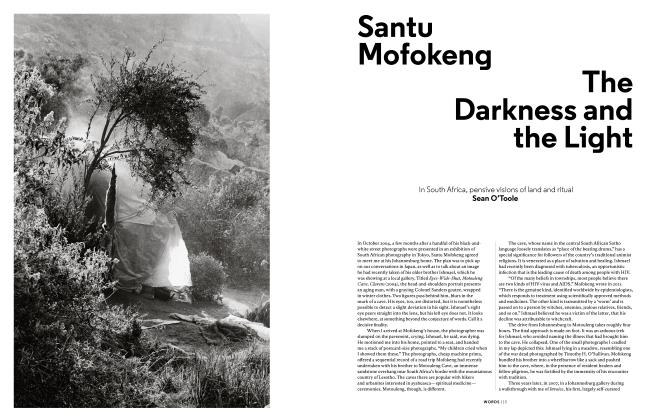

WordsSantu Mofokeng The Darkness And The Light

Winter 2019 -

Pictures

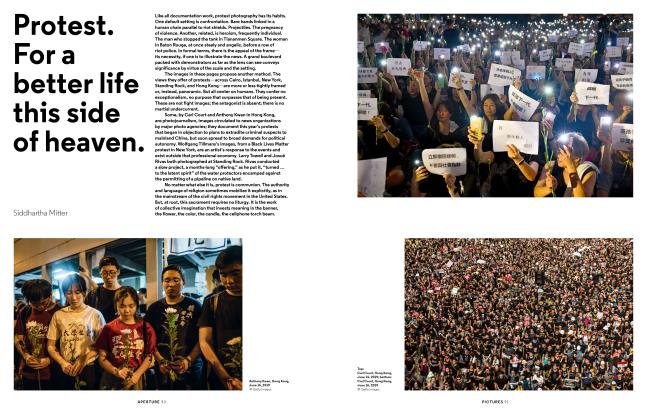

PicturesProtest. For A Better Life This Side Of Heaven.

Winter 2019 -

Pictures

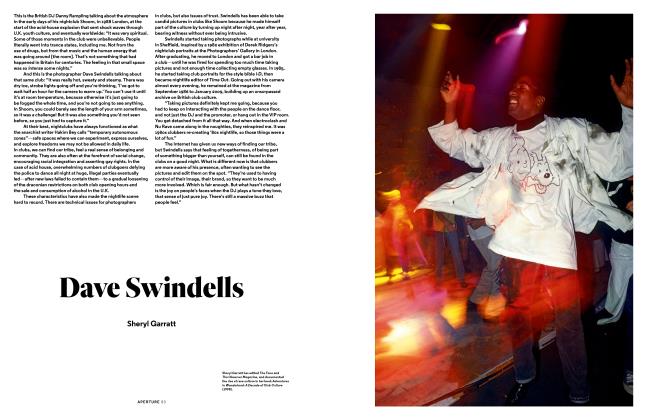

PicturesDave Swindells

Winter 2019 -

Pictures

PicturesHarit Srikhao

Winter 2019 -

Pictures

PicturesProject: Wolfgang Tillmans Are Photographs Words?

Winter 2019 -

Pictures

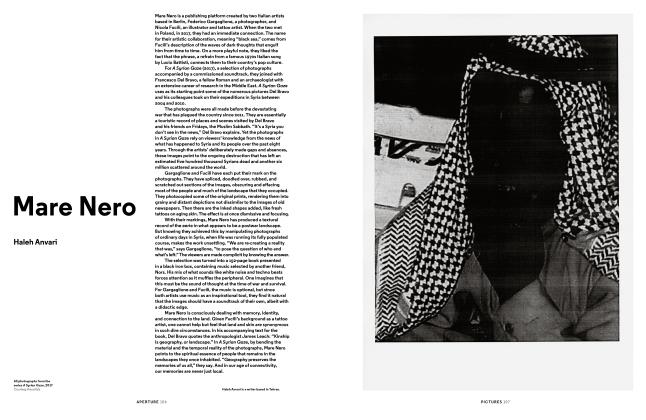

PicturesMare Nero

Winter 2019