Words

The Shadow And The Flash

Iñaki Bonillas in Conversation with Iván Ruiz

Fall 2019 Iñaki Bonillas Iván RuizIn 2003, Iñaki Bonillas inherited a collection from his Basque grandfather, José Rodríguez Plaza, who had arrived in Mexico as an exile from Spain decades earlier. J. R. Plaza had an expansive imagination. He photographed himself dressed up as various characters from American Westerns and made business cards for jobs he never held. The J. R. Plaza archive would become an enduring long-term project for Bonillas, one of Mexico’s most insightful artists when it comes to transforming the field of photography. His rigorous, decidedly experimental methodology encompasses photography, video, installation, site-specific interventions, and artist’s books.

Bonillas, who in his youth worked as an “assistant to the assistant” in the photographer Carlos Somonte’s studio, has long been interested what he calls the “extra-photographic aspects of the medium.” In his deeply researched exhibition projects, from interventions inside Casa Luis Barragan to collaborations with bookbinders, he pushes beyond the two-dimensional to plumb private and collective memory. His work integrates photography in a creative process wherein reality, fiction, and the fluctuating worlds of word and image all coexist.

All of this was on display last year in Ya no, todavía no (No longer, not yet), his first solo exhibition at Kurimanzutto, in Mexico City, which drew upon the techniques and skills of analog photography and what the filmmaker Robert Bresson has referred to as “the intelligence of the hands.” “I am a curious, restless person,” Bonillas told Ivan Ruiz when they spoke recently at Bonillas’s studio in the Roma neighborhood of Mexico City. “I constantly feel the impulse to extend my research to other territories.”

I’m like a kind of attic photographer, someone who’s more attuned to the residue of what someone has forgotten in the darkroom.

Iván Ruiz: Inaki, you started your ascent in the world of photography very early. How do you situate yourself in relation to your precociousness?

Inaki Bonillas: I don’t know exactly why, but one day, when I was very young, I expressed to my mother that I had a certain interest in photography. This would have been in the early ’90s, when I was still in high school, and at that time, any kind of extracurricular activity was quite welcome in my home. My mother was a single mother, so having the kid occupied in the afternoons was a positive thing. We looked into possible photography courses to which I could apply. I studied at the Nacho Lopez Photography School very briefly—I never finished the course, but my interest in photography remained.

At the same time, in my high school, there was an older student who was already a precocious artist in his own right. He put his library, made up primarily of art history books, but with a specific focus on the so-called Conceptual art period, at my disposal.

Those were some of the first art history books to inspire me.

IR: What specifically sparked your curiosity about what we now call analog photography?

IB: From the moment I began studying photography, I had to study traditional analog methods. That being said, the digital era was already approaching. So, in a way, I began studying something that was already obsolete from the outset, something on the verge of dying out, or of transforming into something else. I started working with a medium that was already the memory of itself. Certainly, the work of artists like Jan Dibbets, Sol LeWitt, John Hilliard, Hanne Darboven, and John Baldessari, who incorporated photography into their practices, resonated with me. I also sensed that the majority of my colleagues who studied fine arts were always complaining that the colleges in those days, at least in Mexico, were very focused on traditions that were deeply rooted in the technical, and there wasn’t necessarily any intellectual development. So I thought I could skip that stage and not follow the path of all my academic colleagues.

IR: Another important part of your initial training was assisting photographers, one of whom was Carlos Somonte.

IB: Not only was Carlos Somonte a very well-known photographer, but he was also my uncle. I barely knew him when I was young, but my mother noticed that I was taking my studies in photography seriously and urged me to contact my uncle to see if I could take things a step further.

I was still in school, and every day after class, I would head straight to his studio, and that’s where I spent all my afternoons.

I was actually the assistant to the assistant, because I was still too young to have that much responsibility. But that’s where something important occurred for me. In a way, being the assistant to the assistant, you become responsible for all things peripheral to photography: you are the one who installs the lights, who prepares the cyclorama, the one who takes the film rolls to the lab, the one who comes back to the lab an hour later to see if the shots came out underexposed or overexposed. In short, you are the one who is in charge of preparing everything that’s needed in order to take a photograph, but you do not take the photograph yourself. This limit allowed me to begin to work in the margins of the notion of the photographic, and to become more interested in the extra-photographic aspects of the medium.

IR: In this country, at least since the founding of the Consejo Mexicano de Fotografia in the ’70s, there have been clearly defined boundaries between the practices of photojournalism, documentary, and artistic photography, but not so much the area of conceptual photography. Would you define yourself as a conceptual photographer?

IB: Much of my work has been tied to the photographic archive— a familial photographic archive that I tend to consult. All this has made me think that in reality I’m more like a kind of attic photographer, someone who’s more attuned to the residue of what someone has forgotten in the darkroom, of what someone has abandoned, of the things that are in disuse, or obsolete— that is, materials that have gone unnoticed, or have been left in a space lacking in the conditions necessary for their preservation, and that end up undergoing alterations, perhaps because of a moth, humidity, a fire. And this is the territory in which I feel I move best, the territory of the antiquarian, of the restorer.

In my work there is always this kind of secret conversation with a dead or anonymous person, with someone who underlined a book, for example, and left a series of annotations, or simply with solitary and forgotten images that have served as inspiration forme.

IR: Why do you think your work draws attention in the world of photography?

IB: I have the sense that as time has gone by, photography as a field has become more expanded and expandable, and in a certain sense that has been good for me, because now my work fits more naturally in the world of photography. Laszlo Moholy-Nagy mentions that the most surprising possibilities can be discovered in the photographic material in itself, and I couldn’t be more in agreement with him.

It is increasingly common for artists to work with images that were not necessarily originally produced by them, as I have almost always done, and these are no longer considered appropriations, but works in their own right. I get the feeling that before the distrust in these practices was generalized, but little by little that has changed. So, I imagine for all these reasons, my work has been shown, cited, and represented in this sphere of the art world called photography.

IR: Let’s go back to your background, to your intellectual biography and the texts that made an impression on you, which have a lot to do with conceptual photography and also with the relationship between photography and the visual arts in general.

IB: Well, in 2003, I inherited this collection from my family, an archive that I named J. R. Plaza, which was how my maternal grandfather used to abbreviate his own name. In working with this archive, I discovered a whole series of images where my grandfather appears dressed as a cowboy, seeming to imitate characters from American Westerns or in the style of the Marlboro Man. My grandmother gave me a small diary my grandfather kept in Wyoming during a three-month stay; I imagine he thought that going to spend a summer in Wyoming as a young man would allow him to fulfill his dream of becoming sort of a John Wayne, but instead of that, what one reads in the diary is a series of misfortunes, everything turning out badly. And it would seem that my grandfather had returned to Mexico City after the fact and had continued with his search for his identity, but now from the comfort of a photo studio, and so he created these sets much in the style of Cindy Sherman, where he would come up with an outfit, a costume, and ask his friends to pose, duplicating images from cowboy films. All this material gave rise to a work entitled The Shadow and the Flash, 2007, whose namesake is a short story written by Jack London about two childhood rivals who as adults compete to discover the secret of invisibility, or the way to disappear, as perhaps my grandfather had tried to do: in the whiteness of the pages of his diary first, and in the darkness of the photographic negatives afterward.

I spend a lot of time looking for traces of images that are hidden somewhere.

Subsequently, I also inherited from my grandfather a card wallet, in which he had accumulated all of the cards from the various jobs he had held over the course of his life. He was mainly an aluminum seller for a Canadian company called Alcan.

And in some of the empty slots left in this card holder that he had fashioned for himself, he had typed up cards with the names of jobs he would have liked to have had and that, in reality, he never had—like wood cutter, front-desk manager, model, mechanic. When I saw this card wallet, it occurred to me that there was one card my grandfather forgot to add: the card for self-portraitist, which was actually what he had dedicated his entire life to, an impossible job—who would hire you as a self-portraitist?

In order to certify that he had, in fact, been a self-portraitist,

I searched for a self-portrait for each of these fictitious cards and also played a bit with their opposites—a shepherd who sleeps on the grass and a representative who flies and travels all the time, and so on.

All this is to say that often in my work texts come first, and then I imagine the sort of images that should come along. So, it is not uncommon that a book, or a reading, is reflected in the photographic archive—and sometimes the opposite.

IR: I think of you not only as this photographer who’s behind the scenes, but also as this figure who is undercover in order to enact a detective-like search.

IB: Yes, I spend a lot of time looking for traces of images that are hidden somewhere. That is what I did at Casa Luis Barragan, with the project Secretos (Secrets, 2016), where the figure of the detective was very present. Back in 2003, I believe, I was part of a group exhibition at Casa Barragan. At that time, I decided to occupy a tiny abandoned nail in a wall with a photograph that represented solitude, quietness, and it went completely unnoticed, unseen. And that was the idea—to occupy a space with silence. So it surprised me to receive, after fourteen or fifteen years, an invitation from Estancia FEMSA to develop an investigation throughout the entire house.

For this second exploration—and hence the title—I thought about the so-called secrets that nuns in convents used to hide inside books, a practice that is not at all alien to the books we see in Casa Barragan: if one has the opportunity simply to view them from above, one can see they’re filled with all kinds of tiny papers, annotations, archived inside the books. But there is also a much more direct relationship with photography, which is that this house is, in my opinion, one of the most photogenic houses of the twentieth century; it is, in a way, a house made to be constantly photographed. But in order to maintain this visual appeal, this pristine quality, every element must be perpetually in its place, nothing out of order, and for this to happen there must be a negative of the house, a kind of second house inside the main one to accommodate things that would spoil the photograph and distort the discourse that Luis Barragan so carefully developed over the course of many years of practice within it. And for this reason,

I decided to intervene only in the hidden spaces throughout the house—inside wardrobes, closets, spaces behind doors.

There are nearly ninety doors in Casa Barragan, and one can’t help but ask oneself what is behind each of these doors. At one point when I was exploring the house, I was surprised to find, upon moving pieces of furniture that had been standing there for some forty, fifty years on the colored carpets of this house, that the imprints, the marks, were so deep, the traces so pronounced.

I thought, Surely, if we are to refer to the most exact floorplans of the house, these marks should be part of that drawing, because they are like hidden proto-photographs in the floor. So, what I did was photograph them and put the pictures inside the most appropriate place in the house: the file chest of drawers of the architect’s studio.

IR: I’m very interested in speaking more about the work you did with your grandfather’s archive. How many years from when you first inherited the archive did it take? What did it mean for you to inherit this archive, and what were the ways in which you reinvented your own practice?

IB: In 2002, I think, I started working with Galerie Greta Meert in Brussels, and the next year we planned an exhibition. I decided to move to Belgium for a year, and I decided—please don’t ask me why—to bring these thirty family albums, which I had recently... maybe not inherited, strictly speaking, but perhaps taken responsibility for.

I had no idea that I would spend the next twenty years occupied with this material.

Initially, of course, I had no idea that I would spend the next twenty years occupied with this material or that the work I was doing was considered in any way related to archival practices.

I just had to take something with me, and I took these albums, but I was so unclear about what to do with them that in the exhibition where I first included them, they went completely unnoticed. What I did, much to the gallery owners’ headache, was reorganize the entire gallery library. What was most within reach of the viewer were the thirty family albums with which I’d traveled from Mexico to Brussels, and then next were all of the dossiers of the artists represented by the gallery—another kind of family archive. Then, on the next step, which was a little further out of arm’s reach, I put all of the monographs of the artists represented by the gallery; then further up, all the catalogs of group exhibitions in which any of the artists of the gallery had participated; and then toward the top, where one could only reach with the help of a ladder, all the books that had no relation to the gallery’s artists. You could say this was my first intervention, if there was one: the simple fact of having transported the archive from one library—my grandfather also had these family albums interspersed with the books on his bookshelves— to another.

The next project I presented was called Pequena historia de la fotografia (Little history of photography, 2003), an homage to the essay of the same title by Walter Benjamin. And all I did was open this material to the light of day. What happens when you go through the pages of these albums, or any other image collection, is that you remember some images but then forget various others. My interest was to see what this material was made of, and to bring it to light without leaving anything forgotten. Using 4-by-5 slide film, I photographed each of the double spreads in the thirty albums and organized the slides in thirty light boxes—one box per album— and I put these light boxes on display on a giant table that ran the length of the space of the Antwerp Museum of Modern Art, where they were shown.

So, my work with the archive reflects the progression from the surface to the depth of the photographs that comprise it, a journey from the plural to the singular, one that first has more to do with the history of photography and then with the person who constructed this archive, my grandfather, who has almost become a fictional character. I often encounter viewers of my work who say, “There’s no way your grandfather could have done all this, it’s obvious you invented all.” So I think this has been the trajectory, more or less—going from putting the archive as it is on display and ending with what could be a kind of death of the archive, where what I do is photograph the marks that have been left behind by the photographs on the plastic protecting them. My grandfather was a compulsive smoker, and the amount of nicotine and dust that accumulated between the photographs and the plastic covers is infinite.

I could continue working eternally with this legacy, because for me it is a double of the world, with infinite possibilities, but I am a curious, restless person, and I constantly feel the impulse to extend my research to other territories.

IR: I’d like to go back to the first question, which had to do with precociousness. As opposed to other countries, in Mexico the market for photography is lacking a professional circuit; there are only a few galleries specializing in photography. You were represented early on by a gallery, and now you are newly represented by Kurimanzutto, a gallery with an international reputation—and locations in both Mexico City and New York— that has a rather significant circulation and impact. What exactly is your position as a young artist who entered the market fairly quickly and who is now globally positioned?

IB: There is an overpopulation of artists, and we can’t all exhibit at the same time in the same institutional venues. The space of a gallery and the particular ramifications that go along with it, like art fairs, have been convenient for developing my investigations— in the first place, because they tend to come with great support.

The gallerists that I work with have confidence in what I do and embrace my projects, and this allows me to develop my investigations with the pause and rhythm that my work requires. Some of my projects take years of work, from the readings I have to do to the process of trial and error I go through in order to define a work formally. So it is deeply gratifying, the freedom with which one can work in these types of art spaces. For me, fundamentally, there is little difference between presenting work in a fair, in a gallery, or in a museum, because what I do involves the same kind of research and studio, or archival, work.

IR: Perhaps to conclude, could you talk about your recent exhibition at Kurimanzutto, Ya no, todavia no (No longer, not yet, 2018)?

IB: It was a big show, where I presented more than twenty works, some photographic, some video works. It was called Ya no, todavia no because it had to do with techniques, processes, materials that are no longer as present and useful as they were, but not yet completely gone. So I tried to produce the whole show with the aid of these kinds of skills and approaches. One of the works, for example, is Luz de seguridad (Safelight, 2018), a sequence of photographic images of the process of lifting a piece of photographic paper from the developing tank. They were produced in a darkroom, something about to disappear, and then painted by hand—a technique even more obsolete—so as to give the impression of the typical red light used in the same darkroom. And I also did an homage to Daido Moriyama, a work with a title borrowed from him, Adios fotografia (Bye bye photography, 2018). Here I asked an actress to portray, with her hands only, a photographer in action. What we see is nothing but the gestures of the hands while taking a picture and the voids that form around those hands where a camera no longer is used—yet it is somehow still there.

Ivan Ruiz is a researcher of contemporary art and the director at the Institute of Aesthetic Research at the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico in Mexico City.

Translated from the Spanish by Elianna Kan.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

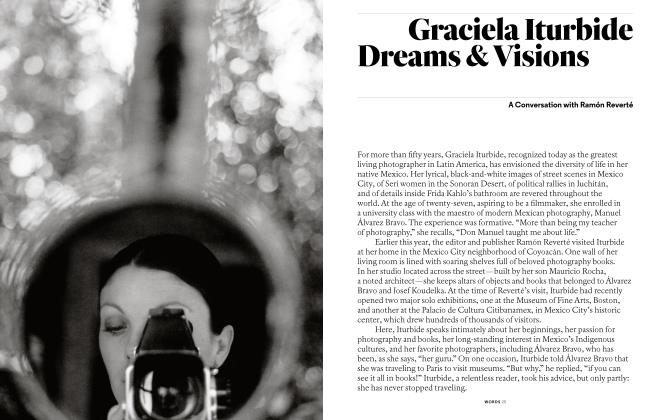

WordsGraciela Iturbide: Dreams & Visions

Fall 2019 By Ramón Reverté -

Pictures

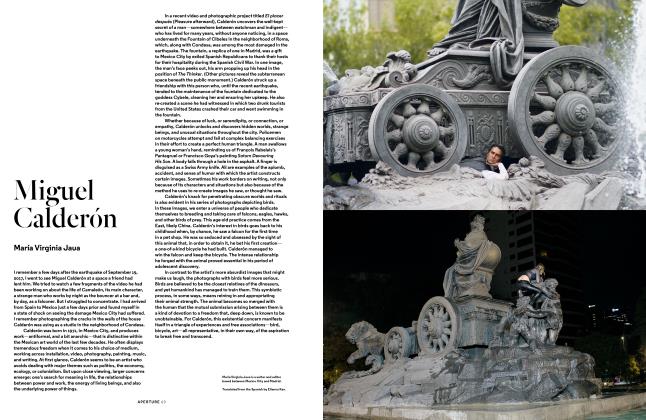

PicturesMiguel Calderón

Fall 2019 By María Virginia Jaua -

Words

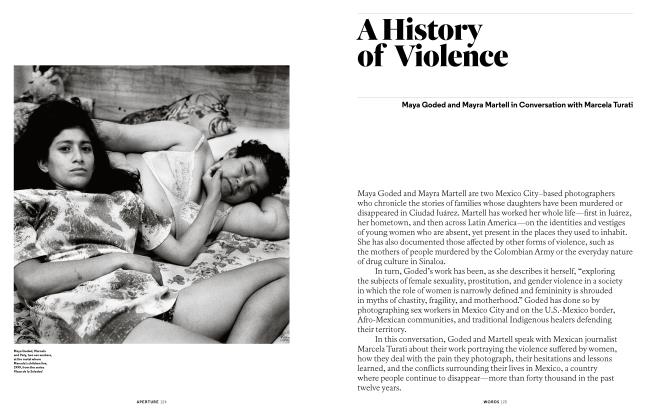

WordsA History Of Violence

Fall 2019 By Marcela Turati -

Words

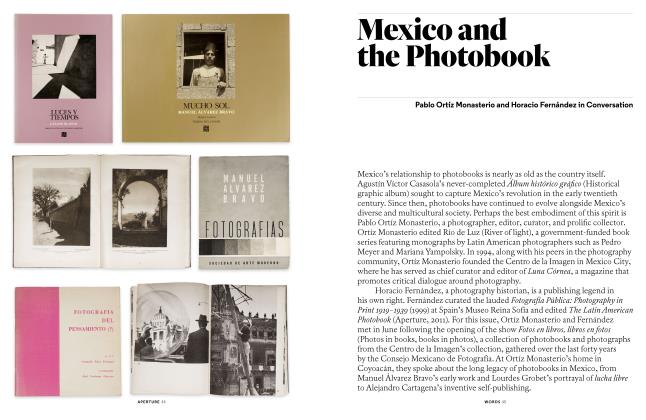

WordsMexico And The Photobook

Fall 2019 -

Words

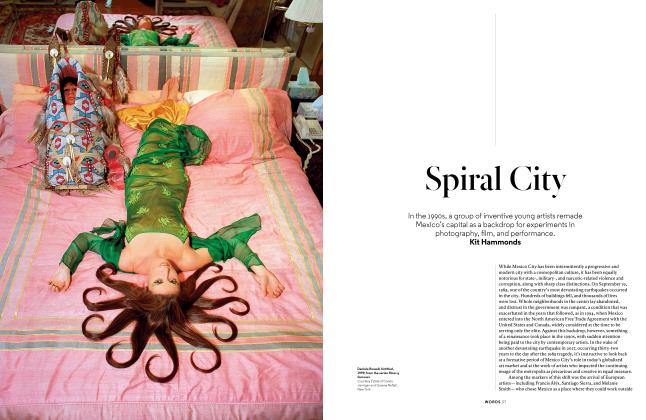

WordsSpiral City

Fall 2019 By Kit Hammonds -

Pictures

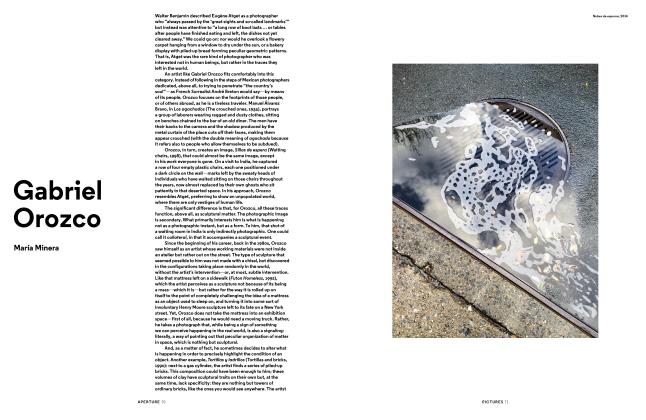

PicturesGabriel Orozco

Fall 2019

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Places

-

Words

WordsJohn Divola & Mark Ruwedel

Fall 2018 By Amanda Maddox -

Words

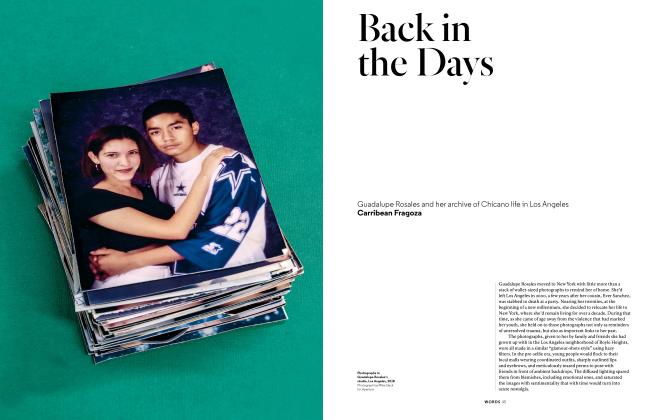

WordsBack In The Days

Fall 2018 By Carribean Fragoza -

Pictures

PicturesRinko Kawauchi

Summer 2015 By Lesley A. Martin -

Words

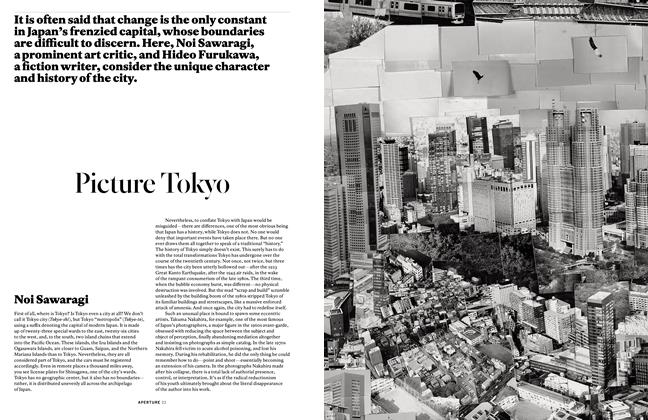

WordsPicture Tokyo

Summer 2015 By Noi Sawaragi, Hideo Furukawa -

Pictures

PicturesKikuji Kawada

Summer 2015 By Ryuichi Kaneko -

Pictures

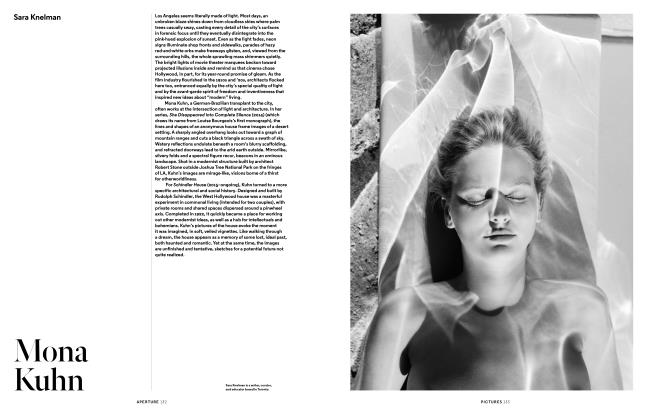

PicturesMona Kuhn

Fall 2018 By Sara Knelman

Words

-

Words

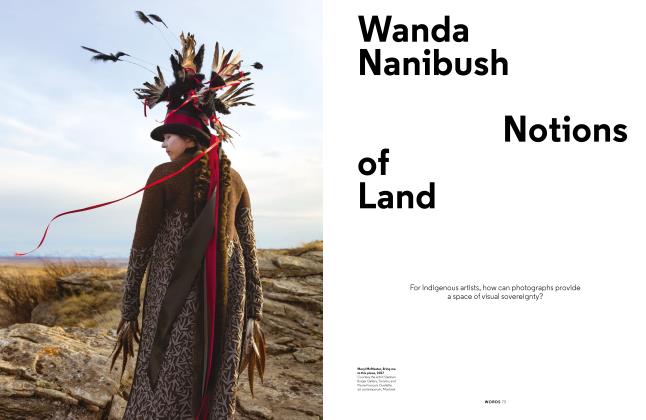

WordsWanda Nanibush Notions Of Land

Spring 2019 -

Words

WordsAnnabelle Selldorf

Spring 2020 -

Essay

EssayFrom Ecstasy To Agony: The Fashion Shoot In Cinema

Spring 2008 By David Campany -

Words

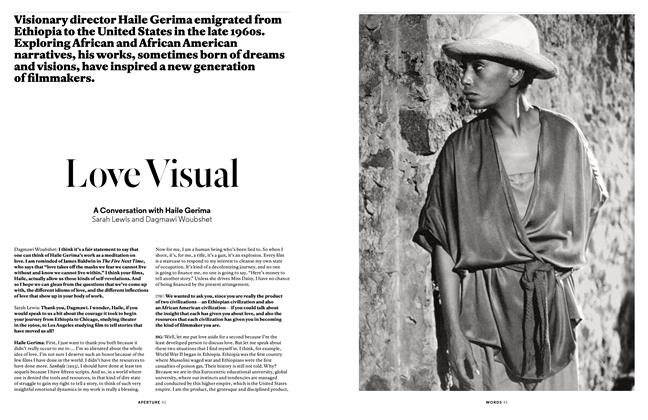

WordsLove Visual

Summer 2016 By Haile Gerima, Sarah Lewis, Dagmawi Woubshet -

Words

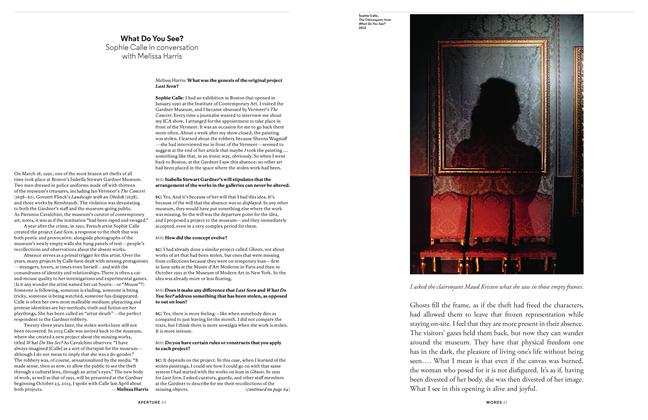

WordsWhat Do You See?

Fall 2013 By Melissa Harris -

Words

WordsThe Image World Is Flat

Spring 2013 By Penelope Umbrico