Pictures

Miguel Calderón

Born in Mexico City, Miguel Calderón produces antiformal, and anarchic, work that is distinctive within the Mexican art world of the last few decades.

Fall 2019 María Virginia JauaI remember a few days after the earthquake of September 19, 2017, I went to see Miguel Calderón at a space a friend had lent him. We tried to watch a few fragments of the video he had been working on about the life of Camaleón, its main character, a strange man who works by night as the bouncer at a bar and, by day, as a falconer. But I struggled to concentrate. I had arrived from Spain to Mexico just a few days prior and found myself in a state of shock on seeing the damage Mexico City had suffered.

I remember photographing the cracks in the walls of the house Calderon was using as a studio in the neighborhood of Condesa.

Calderon was born in 1971, in Mexico City, and produces work—antiformal, and a bit anarchic—that is distinctive within the Mexican art world of the last few decades. He often displays tremendous freedom when it comes to his choice of medium, working across installation, video, photography, painting, music, and writing. At first glance, Calderon seems to be an artist who avoids dealing with major themes such as politics, the economy, ecology, or colonialism. But upon close viewing, larger concerns emerge: one’s search for meaning in life, the relationships between power and work, the energy of living beings, and also the underlying power of things.

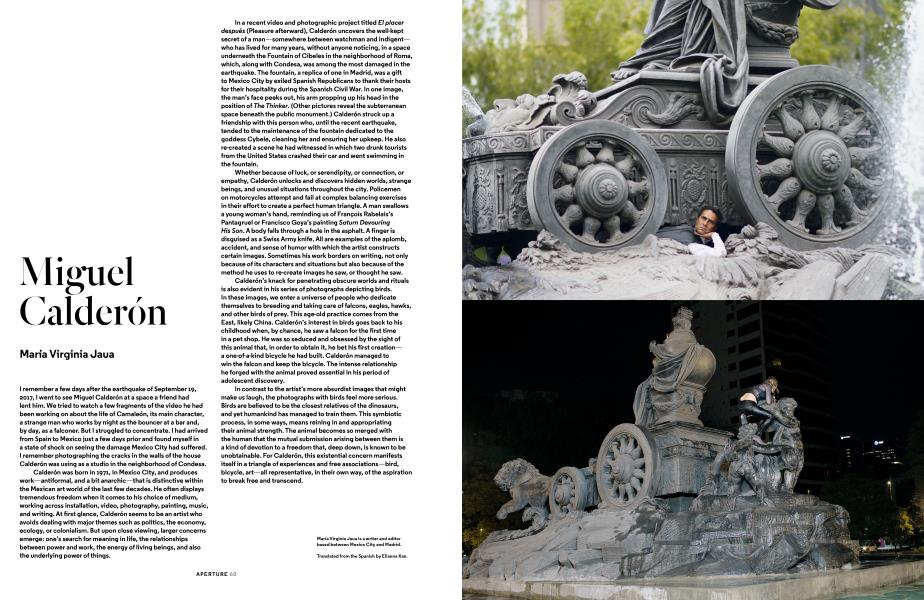

In a recent video and photographic project titled El placer despues (Pleasure afterward), Calderon uncovers the well-kept secret of a man—somewhere between watchman and indigent— who has lived for many years, without anyone noticing, in a space underneath the Fountain of Cibeles in the neighborhood of Roma, which, along with Condesa, was among the most damaged in the earthquake. The fountain, a replica of one in Madrid, was a gift to Mexico City by exiled Spanish Republicans to thank their hosts for their hospitality during the Spanish Civil War. In one image, the man’s face peeks out, his arm propping up his head in the position of The Thinker. (Other pictures reveal the subterranean space beneath the public monument.) Calderon struck up a friendship with this person who, until the recent earthquake, tended to the maintenance of the fountain dedicated to the goddess Cybele, cleaning her and ensuring her upkeep. He also re-created a scene he had witnessed in which two drunk tourists from the United States crashed their car and went swimming in the fountain.

Whether because of luck, or serendipity, or connection, or empathy, Calderon unlocks and discovers hidden worlds, strange beings, and unusual situations throughout the city. Policemen on motorcycles attempt and fail at complex balancing exercises in their effort to create a perfect human triangle. A man swallows a young woman’s hand, reminding us of Franpois Rabelais’s Pantagruel or Francisco Goya’s painting Saturn Devouring His Son. A body falls through a hole in the asphalt. A finger is disguised as a Swiss Army knife. All are examples of the aplomb, accident, and sense of humor with which the artist constructs certain images. Sometimes his work borders on writing, not only because of its characters and situations but also because of the method he uses to re-create images he saw, or thought he saw.

Calderon’s knack for penetrating obscure worlds and rituals is also evident in his series of photographs depicting birds.

In these images, we enter a universe of people who dedicate themselves to breeding and taking care of falcons, eagles, hawks, and other birds of prey. This age-old practice comes from the East, likely China. Calderon’s interest in birds goes back to his childhood when, by chance, he saw a falcon for the first time in a pet shop. He was so seduced and obsessed by the sight of this animal that, in order to obtain it, he bet his first creation— a one-of-a-kind bicycle he had built. Calderon managed to win the falcon and keep the bicycle. The intense relationship he forged with the animal proved essential in his period of adolescent discovery.

In contrast to the artist’s more absurdist images that might make us laugh, the photographs with birds feel more serious.

Birds are believed to be the closest relatives of the dinosaurs, and yet humankind has managed to train them. This symbiotic process, in some ways, means reining in and appropriating their animal strength. The animal becomes so merged with the human that the mutual submission arising between them is a kind of devotion to a freedom that, deep down, is known to be unobtainable. For Calderon, this existential concern manifests itself in a triangle of experiences and free associations—bird, bicycle, art—all representative, in their own way, of the aspiration to break free and transcend.

María Virginia Jaua is a writer and editor based between Mexico City and Madrid.

Translated from the Spanish by Elianna Kan.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

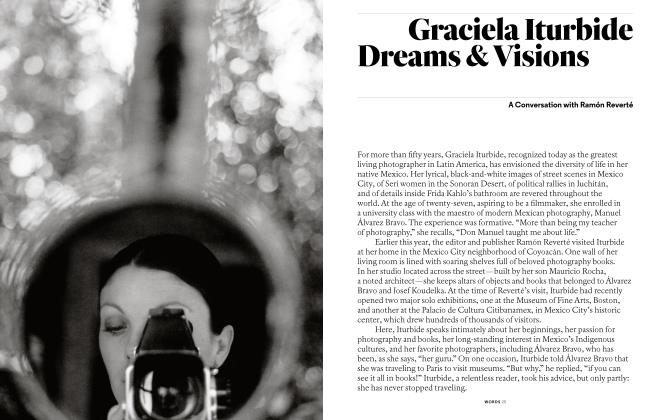

WordsGraciela Iturbide: Dreams & Visions

Fall 2019 By Ramón Reverté -

Words

WordsThe Shadow And The Flash

Fall 2019 By Iñaki Bonillas -

Words

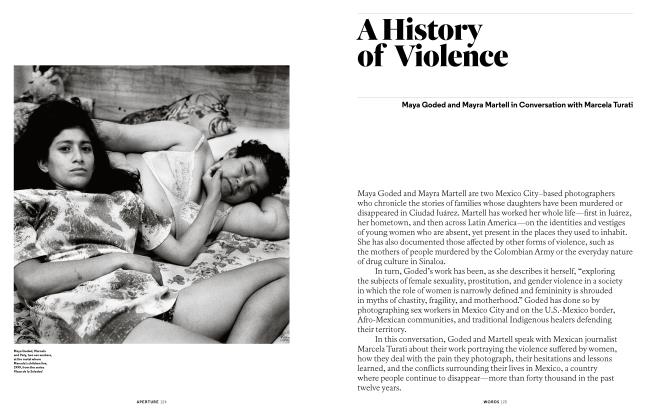

WordsA History Of Violence

Fall 2019 By Marcela Turati -

Words

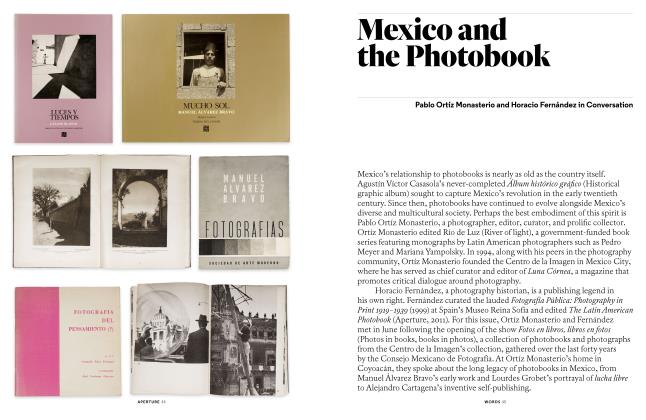

WordsMexico And The Photobook

Fall 2019 -

Words

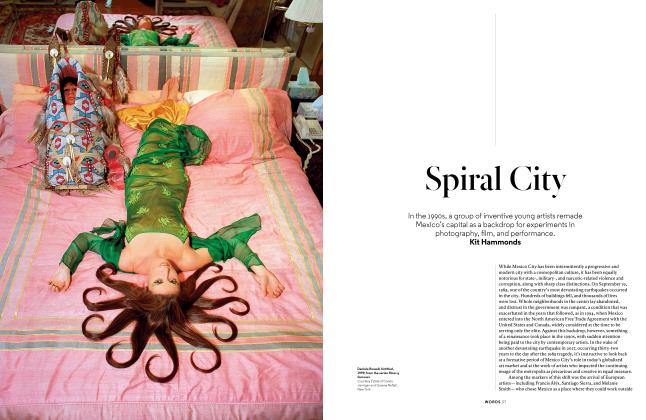

WordsSpiral City

Fall 2019 By Kit Hammonds -

Pictures

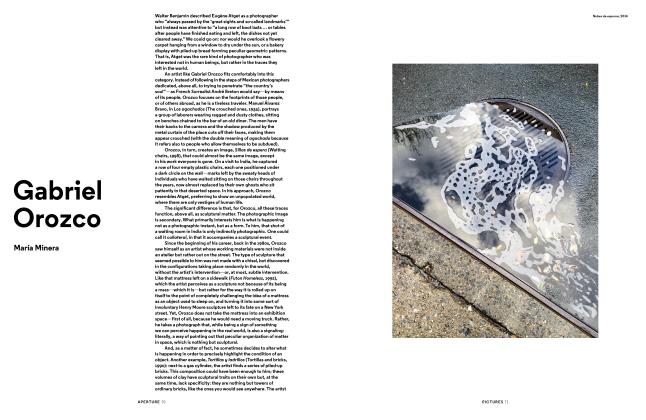

PicturesGabriel Orozco

Fall 2019

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Places

-

Words

WordsJohn Divola & Mark Ruwedel

Fall 2018 By Amanda Maddox -

Words

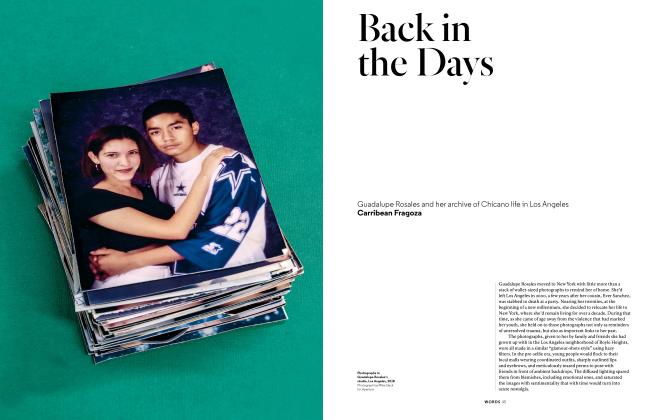

WordsBack In The Days

Fall 2018 By Carribean Fragoza -

Words

WordsThe Shadow And The Flash

Fall 2019 By Iñaki Bonillas -

Words

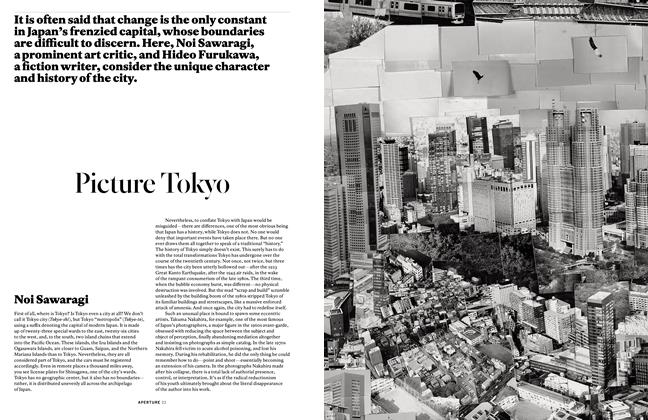

WordsPicture Tokyo

Summer 2015 By Noi Sawaragi, Hideo Furukawa -

Pictures

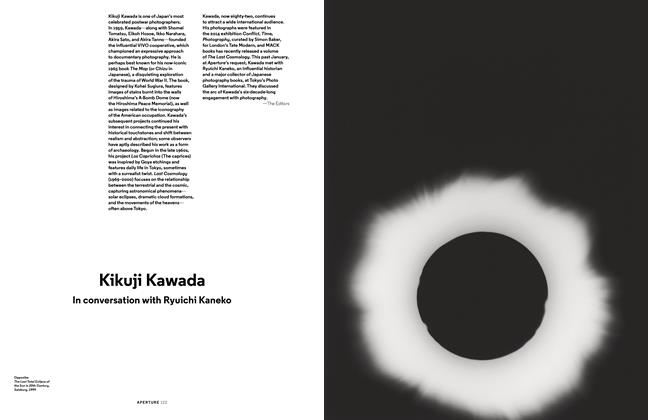

PicturesKikuji Kawada

Summer 2015 By Ryuichi Kaneko -

Pictures

PicturesTorbjørn Rødland: Into The Light

Fall 2018 By Travis Diehl