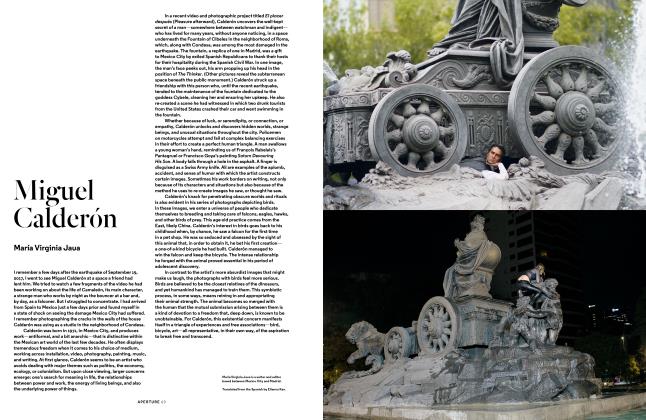

For more than fifty years, Graciela Iturbide, recognized today as the greatest living photographer in Latin America, has envisioned the diversity of life in her native Mexico. Her lyrical, black-and-white images of street scenes in Mexico City, of Seri women in the Sonoran Desert, of political rallies in Juchitán, and of details inside Frida Kahlo’s bathroom are revered throughout the world. At the age of twenty-seven, aspiring to be a filmmaker, she enrolled in a university class with the maestro of modern Mexican photography, Manuel Alvarez Bravo. The experience was formative. “More than being my teacher of photography,” she recalls, “Don Manuel taught me about life.”

Earlier this year, the editor and publisher Ramon Reverte visited Iturbide at her home in the Mexico City neighborhood of Coyoacán. One wall of her living room is lined with soaring shelves full of beloved photography books.

In her studio located across the street—built by her son Mauricio Rocha, a noted architect—she keeps altars of objects and books that belonged to Alvarez Bravo and Josef Koudelka. At the time of Reverte’s visit, Iturbide had recently opened two major solo exhibitions, one at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and another at the Palacio de Cultura Citibanamex, in Mexico City’s historic center, which drew hundreds of thousands of visitors.

Here, Iturbide speaks intimately about her beginnings, her passion for photography and books, her long-standing interest in Mexico’s Indigenous cultures, and her favorite photographers, including Alvarez Bravo, who has been, as she says, “her guru.” On one occasion, Iturbide told Alvarez Bravo that she was traveling to Paris to visit museums. “But why,” he replied, “if you can see it all in books!” Iturbide, a relentless reader, took his advice, but only partly: she has never stopped traveling.

My camera was a pretext for getting to know Mexico’s traditions and culture.

Ramón Reverté: I’d like to ask about the beginning of your career—I’m sure you’ve probably gotten the same question a thousand times—how did you come to photography? And I’m curious whether from an early age you enjoyed painting and photography, or is it an interest that was ignited as a result of your meeting Manuel Alvarez Bravo?

Graciela Iturbide: In my family, there wasn’t an affinity for any of those things. I wanted to be a writer from a young age. My father, who was very conservative, wouldn’t let me attend university because women were supposed to stay at home. I married very young. I quickly had three children. I wanted to study philosophy and literature, but I couldn’t because, with three children, I had no time.

At an early age, I had a camera, and I took photographs because my father was an amateur photographer. I loved to go into his closet and steal his photographs, which led to various punishments, but my father should have been proud I was stealing his photographs.

In 1969, when I was already married and twenty-seven years old, I heard on the radio that there was a university where you could study film, and I enrolled. It was very easy to get admitted; everyone got in because it was when the film school was just getting started. That’s where I met Manuel Alvarez Bravo, who was giving photography classes. I had the book he had published during the 1968 Olympics in Mexico and brought it to him so he could sign it. I asked if I could take his classes, and he said yes. No one went to his classes because everyone wanted to be film directors. After two days, he said, “Listen, I’d like you to be my achichincler and I said, “Of course.” An achichincle in Mexico is the person who assists the construction worker and does a bit of everything.

That’s how my life changed. We spoke a lot about painting.

We listened to a lot of music. It was my salvation in life because he had a very different way of thinking than my family. On one occasion, he told me, “You know what, Graciela, divorces help because one can start anew.” It was like he was opening me to life. Within a year, I was divorced, without any struggle, without any issue.

RR: Tell me about your parents. Did you go to exhibitions when you were little?

GI: Not so much to exhibitions, but we went to concerts, to the opera, to musical things. Sometimes my father would take us to the Cervantino Festival. I was very young then and was somewhat interested in cultural things. My parents’ parents had haciendas. With the revolution, and then under President Lazaro Cardenas, they lost everything. My father had to work from a young age to support his family. At the age of sixteen, he started working in Oaxaca with the archaeologist Alfonso Caso, strangely enough, as his assistant. He never had a formal profession. My mother played piano recitals when she was young, and she loved classical music. She also drew. She was more sensitive to those kinds of things.

But I wouldn’t say it was a cultured family. It was a bourgeois family.

RR: When you decided to study film, was it because you liked film, or because you saw some kind of escape? Was it a conscious decision?

GI: Yes, because I wanted to. I told myself, In film, there is a script, and I want to study literature, so I might as well study film and see what I can do from there. I did it out of my need to study something because I had never been allowed to. It was an urgent need within myself.

RR: So photography wasn’t an interest of yours at that time?

GI: I took photographs as a child because my father gave me a camera when I was eleven years old. But I took photographs of things like churches, from the bottom up, stranger things than my cousins and siblings photographed. I always saw my father taking photographs, and he did a bit of film, but just as a hobby.

RR: So it’s really Don Manuel who introduced you to the world of photography?

GI: More than being my teacher of photography, Don Manuel taught me about life. I was already developing my own film because I had taken some photography classes before taking lessons with Manuel. So one time I asked him, “Maestro, how do you properly develop a roll of black-and-white film?” And he responded, “You know, Graciela, go to the photography store, buy yourself a roll of film, read the instructions, and that’s how you do it.” He never told me whether my photographs were good or bad. Never. But he spoke to me a lot about painting. He spoke to me about literature. We listened to opera in the afternoons.

He made me see life in a different way than I had lived it as a child. When I lived with the father of my children, who was a more liberal man than others I had known, it also helped a bit in my development. In my time, it was unlikely for husbands to say, “Yes, yes, of course, go study.” It wasn’t very easy.

RR: How long were you working with Don Manuel?

GI: I worked with Don Manuel for about two years. But I stayed near him all my life, that’s why I live here. When I separated from my partner, I came to live here [the Coyoacan neighborhood of Mexico City] because Alvarez Bravo told me, “They’re selling a little plot of land over there, Graciela. Come here to Coyoacan.”

RR: Photography wasn’t an easy path to making a living.

GI: I’ve had money, I’ve had no money, but when I didn’t have money, there were rolls of film in my refrigerator. I’ve always been taking pictures. At the very beginning, and when I got divorced, the only work I had was for hire for magazines like Mundo medico (Medical world) and Medico moderno (Modern doctor) to go photograph operations.

RR: And what did you photograph?

GI: Births. Once I won an award for a cover that I shot. They paid me monthly. I didn’t have to be there the whole time, only when they commissioned things. It’s the only work I’ve ever had for hire, and I loved it.

RR: What was your first contact with the photography world? Was it at the INI [National Institute of Indigenous Peoples] that you first began?

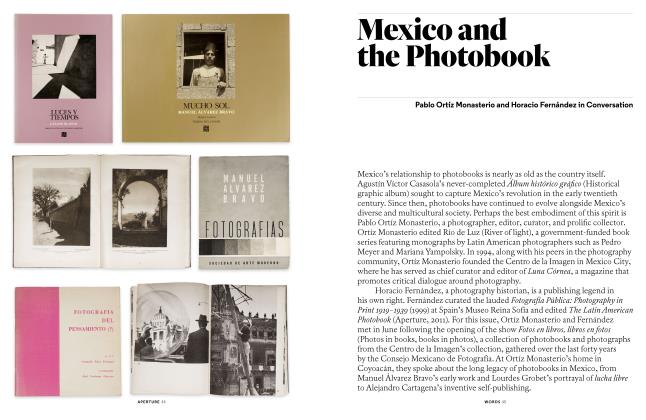

GI: I only did a project with the ethnographic archive at the INI. They made various films and published seven books about this archive under the direction of Pablo Ortiz Monasterio. It was my job to go to the desert with the Seri, and I was fascinated.

RR: The first exhibition you had was in Mexico, and then it traveled to New York.

GI: My first exhibition was at the Orozco Gallery with Paulina Lavista and Colette Alvarez Urbajtel. And then it traveled to New York, with a photographer named Larry Siegel, who had been my teacher here in Mexico before I went to study with Alvarez Bravo. He was the director of the gallery in New York.

RR: So that exhibition had nothing to do with Don Manuel?

GI: Yes, that exhibition came about thanks to Manuel because Larry spoke with him and Manuel decided that it should be three women: Paulina Lavista, Colette, and me. After that, I started to have solo exhibitions.

RR: How did you manage to maintain a family at such a complicated time, in addition to being a woman on your own, in that era in Mexico, with three children?

GI: At the beginning, I had the help of my husband, then I worked {or Medico moderno, and then I worked taking photographs of people who asked me to take photographs.

RR: Portraits?

GI: Lots of portraits, even weddings. I managed. I made money, but I never stopped taking my own photographs. I loved going to the country to be with Alvarez Bravo.

RR: You continually saw Manuel Alvarez Bravo?

GI: Always. Until the end. I always went to see him to speak with him, to listen to music. The thing is that I didn’t want to be his assistant anymore because I didn’t want him to influence me.

I had to cut the umbilical cord.

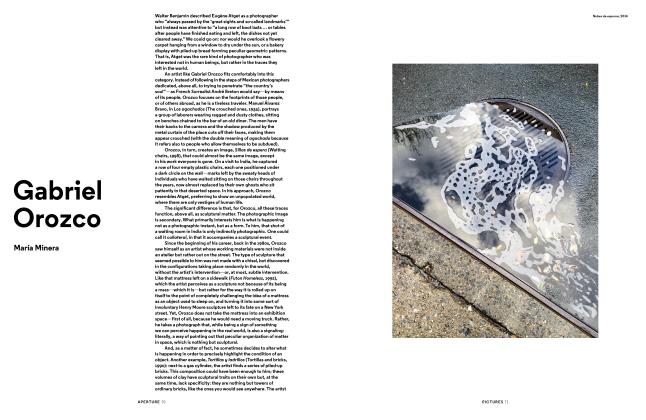

RR: Even though Don Manuel’s influence is present in your work, in the most positive sense, you had a personality all your own in your photography from the very beginning. What is it that truly moves you to take photographs? If you go somewhere now, what motivates you? What is it you want to photograph immediately?

GI: It’s never clear to me what I want to photograph. I always go out walking, even when I’m asked to go photograph something in particular. Surprise is what gets me to pull the trigger on the camera. If I say, “Ay! What a wonder!”—then I press the trigger.

RR: Do you take lots of photographs?

GI: A normal amount. I’m not like the people who came from Magnum. When I took them to Manuel’s house, they saw a dog on the rooftop and started to take a ton of photographs. Manuel always said to me, “Chaca chaca chaca chaca, why so much junk, Graciela? For what?” I learned a different way of taking photographs from Alvarez Bravo, because he always took one or two shots.

If, by chance, he took two, it was already too many. In my case, if I come across something and I like it, I could even take three or four photographs, but I’m not a compulsive photographer. Sometimes I’d take more than one shot in case the negative gets scratched. I always took photographs calmly and enthusiastically and with surprise.

RR: If I were to go with you to photograph for two days in Oaxaca, what would the process be like?

GI: I went to these villages with my camera so that people would know that I was a photographer, and I lived with them, which created solidarity. If I go to a festival where photography is allowed, then I take photographs because it’s allowed. If I see that it isn’t allowed, that people don’t want me to take photographs,

I don’t. I don’t have a telephoto lens, nor a tripod, nor flash.

It’s how I’ve always worked, with a handheld camera but always with people’s complicity. Sometimes, people ask me to take their photographs, like with Magnolia [the iconic photograph from the 1979-89 series Juchitan de lasMujeres]. I was at a cantina, and she was there, and she saw me with my camera and said,

“Ay, ay, my love, take my photo.” I went upstairs with him, or with her, to the room, he got dressed, he made himself up, and I went on taking photographs as he wished, exactly as he wished.

RR: It’s obvious that you share empathy with people.

GI: Yes, it’s beautiful when people ask you to take their photograph. When I go to Juchitan or when I am with the Seri, for me they are not “the other” because they also come to visit me at my house, the same with the Mayo [the people of Sinaloa] as with the Juchiteco. These are people of my country, just like me.

And yes, I have a capacity to feel empathy. I try not to hurt people. That’s why I just have a normal lens that allows me to come close to people, and somehow they accept me even if I don’t ask permission. In some way, with the camera, I am asking. There is an implicit permission.

RR: And have you always worked in 35mm?

GI: I started out with a 35mm camera, and then I had a Hasselblad. I work in two formats, in 6 by 6 and in 35mm. It depends above all if I’m photographing landscapes or objects, which is when I prefer to use a large-format camera.

RR: Do you prefer photographing the world of Indigenous people or the urban world?

GI: My camera was a pretext for getting to know Mexico’s traditions and culture. I also love taking photographs in other parts of the world: India, Panama, Italy. But, of course, my first photographs were in Mexico because it was a way to get to know my culture, which I didn’t have access to as a child because I lived in another world. That’s why I tell you that I owe everything to Alvarez Bravo. He opened my eyes to my country’s culture.

RR: In Mexico City, in addition to what you photographed in the beginning and the series El ba.no de Frida (Frida’s Bathroom, 2005), what other things have you photographed?

GI: My first job was in the historic center. It fascinated me. I love the Zocalo. I love the Templo Mayor. I love everything that goes on in the center of Mexico City. I have photographs from there—of the vendors with their serpents selling medicine, the pachuco, the woman of wax, the man with the frames who walks along the street, the circus—that I hadn’t published until the recent exhibition at the Palacio de Iturbide [Palacio de Cultura Citibanamex in Mexico City].

RR: Have you photographed Coyoacan, the neighborhood where you live?

GI: Now that I live here, no. Before, I would say yes. Now I give the people who live here a bit of respect, because they know I am a photographer. But when I didn’t live here, I would come with Alvarez Bravo to photograph the Barrio del Nino Jesus.

RR: Was Alvarez Bravo already living in Coyoacan? How did you work with him?

GI: Alvarez Bravo lived in Coyoacan since the day I met him until he died. Sometimes I would go with him to the centro because he liked taking photographs of the shopwindows, the mannequins, all of that. But I couldn’t take photographs with him because one day he said to me: “As it says in the Gospels, Graciela, copiaos los unos a los otros—copy one another,” which is to say, “Don’t even think about copying me.” He didn’t have to say it because I’ve never taken a photograph that someone else has taken, never; but it was lovely of him because he said it in a very elegant way.

On the weekends, we would go to the countryside to photograph landscapes. When I was photographing the killing of the goats in the Mixtec community in Oaxaca, if I had gone without my camera,

I wouldn’t have been able to tolerate it; the camera protects you. Imagination is something very important in photography. Someone said, and I think it has to do with Dante, that “the imagination is the well where fantasy rains down.” I was photographing the little goats, but I was also seeing the Bible—I’m not Catholic but there are things in the Bible that I love. I was being reminded of the sacrifice of Isaac. With that reading, I could interpret what I was photographing in my own way, with imagination. Without my camera, I could never have watched a little goat wail.

RR: Are you aware when you take a good photograph, or is it only after developing them that you say, Ah, how beautiful?

GI: Sometimes I’m aware, but I operate with surprise. When I don’t like something, I can’t take a photograph simply because it’s a good document. It has to be something that touches my heart in order for me to push the camera trigger. Besides, you’re always encountering things, it’s not difficult. You go here and you come across something wonderful, you go there and you find something wonderful. For me, it has a lot to do with the imagination. And with fantasy.

It’s interesting that it has to do with fantasy because the photographer is supposedly keeping a record and interpreting the world that she is seeing. Once when I was photographing Juchitan, someone said to me, “That isn’t Juchitan,” and I said, “No, of course this isn’t Juchitan, it is my Juchitan.”

RR: Is there work of yours that you like more than others, with which you are more content?

GI: No. You know, I don’t have a distance from, nor judgment about my work in Juchitan. I can tell you one of the places where I’ve been most happy is Juchitan because of the friendships that I had with people. I don’t have the ability to judge my work. It’s very difficult for me. Only when I have my contacts, and I see them, I once again begin to feel the excitement I’m telling you about. Henri Cartier-Bresson says that the decisive moment is when you take a photograph, but for me there are two decisive moments: one is when you take the photograph and the other is when you discover what it is that you actually photographed. I didn’t remember having photographed Mujer Angel, Desierto de Sonora (Angel Woman, Sonoran Desert, 1979) until I saw the contact sheets.

RR: So sometimes you do get surprised by a photograph you hadn’t thought was going to be very good?

GI: Exactly. That’s why I say that there are two moments for me— not just the moment that Cartier-Bresson describes, but also the decisive moment of having the eye to see what it is you’ve done. And to know to select the image, you have to feel some sort of surprise. One’s intelligence, eye, and heart must be present in equal measure.

RR: Something that surprises me when I speak with you is that you know so many photographers. You know William Eggleston, you know Josef Koudelka quite well, you knew Christer Stromholm, you know Japanese photographers like Eikoh Hosoe. How do you manage to live in a seemingly closed-off world, in your house, which is wonderful, in the middle of Coyoacan, and meet so many photographers in different parts of the world?

GI: When I travel I have the opportunity to meet people. I met Eikoh Hosoe when we were both working on a project for^4 Day in the Life of America (1986). The only one I wanted to meet in my life was Josef Koudelka, and I met him circumstantially in Cartier-Bresson’s house. And I met Cartier-Bresson with Alvarez Bravo. When we were in Paris, we went to see him, and we became very good friends. I met Stromholm in Sweden.

RR: Of the photographers you know, whom do you like the most?

GI: Koudelka, with whom I also have a very close relationship.

Every time I travel to Paris, I go to visit him at his studio. I really like Francesca Woodman, a woman who committed suicide very young, who made a great deal of self-portraits. I love Robert Frank.

I loved Diane Arbus. When I started I wanted to be like Diane Arbus. I would say, Now, that came out as beautiful as a Diane Arbus photograph.

RR: And William Eggleston?

GI: He’s a friend of mine. I’m going to tell you something. In the beginning, I didn’t understand his work. When I saw his first books, I wondered, What is going on with these photographs? It was only later that he began to fascinate me.

RR: And William Klein, by whom you have a number of books— does his work interest you?

GI: I met him in Paris with Cartier-Bresson, but I never ended up having a close relationship with him like I have with other photographers. I bought Klein’s book on New York when I was just beginning to be a photographer, and it’s one of my most prized books. I was enchanted by his way of photographing a city.

RR: Your library is impressive. Do you spend much time looking at photography books?

GI: Every night, I take a photography book, I look at it, I look at it again, I take another, and then I turn to literature, but I look at my photography books a lot, a lot. I love them. I always discover things I hadn’t seen before.

RR: From Latin America, who are your models in photography?

GI: Miguel Rio Branco. Of the first Latin American photographers I met, there was Raul Corrales and [Alberto] Korda in Cuba. The ultra-famous photograph of Che [Guevara], that oddly enough Korda himself did not choose—it had to be chosen by an Italian from his contact sheets. In 2017, I took part in the Colloquium of Latin American Photography and got to meet all of the photographers from Latin America.

RR: Do you identify in any way, for example, with Paz Errazuriz?

GI: She is my friend. I love her work. But do I identify myself with it? I don’t, because our work is utterly different.

RR: Right, they are different, but sometimes you touch on similar subjects.

GI: Perhaps, but I identify with Koudelka, though my work has nothing to do with his. Look, if I’ve fallen in love with the work of any photographer, it’s Koudelka.

RR: Have you met Claudia Andujar?

GI: Yes. I met her in Brazil.

RR: Why do you think there are so many talented photographers in Latin America who are female?

GI: I’ve always been asked if I’ve suffered in my work because I am a female photographer. Never. I want to tell you about a photographer called Maruch Santi'z. She is an Indigenous woman from San Juan Chamula. She photographed a series of rituals that have to do with everything her grandfather told her. Maruch continues to wear traditional clothing, but they don’t like her in Chiapas—her husband left her because she became famous, her parents too, and yet she persistently continues taking photographs.

RR: But in your case, becoming a photographer didn’t impact you.

GI: Well, studying film was an issue for my family. And becoming a photographer was an issue in my family. And getting a divorce was an issue in my family. It wasn’t that easy, now it’s easy, but it wasn’t so easy before. Mexico is very conservative.

RR: And from Mexico? Are there photographers who interest you?

GI: Nacho Lopez fascinates me. I love Rodrigo Moya. In Mexico, there are very good photographers, as much in journalism as in Conceptual art. It is a country that’s flourishing—that’s why I give you the example of Maruch, an Indigenous woman from Chiapas who takes a small course and becomes a tremendous photographer.

RR: Do you have color photographs?

GI: I have thousands of color slides, thousands, but I took them for work that I did for hire. I took a number of color photographs, but I see the world in black and white. When I’m photographing with my camera in black and white, I’m seeing in black and white. When I’m photographing in color, I have to see if yellow goes with purple or not.

RR: So you identify with black and white.

GI: Black and white is more abstract; there are more shadows. In my case, like Cartier-Bresson and Koudelka, if I took two or three color photographs, that’s a lot. As Octavio Paz said, apropos of Alvarez Bravo s photographs, “Reality is more real in black and white. And mind you, Alvarez Bravo also had color photographs.

For me there are two decisive moments: one is when you take the photograph and the other is when you discover what it is that you actually photographed.

RR: But his language is in black and white.

GI: You said what I should have said: my language is in black and white. And in film as well. What little film I’ve done has been in black and white. And the films I most love to watch are in black and white.

RR: What have you done in film?

GI: Right now, I’m editing a work about the life of the painter Jose Luis Cuevas. I started it when I was studying film in 1971.1 recently found the unfinished material. I salvaged it by accident. But if I had gone into film, I would have been a black-and-white filmmaker.

RR: Do you think film has influenced your work?

GI: Yes. My cinematic background and, above all, Italian neorealism. All those filmmakers in black and white. And also [Federico] Fellini, [Ingmar] Bergman.

RR: And Andrei Tarkovsky, about whom you’ve spoken to me once before.

GI: Tarkovsky! Of course! For me, if you ask me whom I’m jealous of in life within the artistic realm, it would be Tarkovsky and Piero della Francesca. Nostalghia (1983) begins with the Madonna in labor who opens, and birds come out. It can’t be! How wonderful!

Painting has also had a tremendous influence. As Alvarez Bravo used to say to me, “Graciela, you have to look at lots of paintings.”

He didn’t tell me you have to look at lots of photography. Once I told him, “I’m going to Paris, maestro.” “And for what?” he asked me. “To see museums.” “But why if you can see it all in books!” I loved that he said that to me. When you see lots of things that are of interest to many different disciplines, it emerges a bit in your work.

RR: In the end, everything is visual education.

GI: Everything.

RR: Is there something pending that you’re looking forward to photographing?

GI: I’m very interested in stones. And then I’d like to continue with air, water, and wind. I went to Japan, and I said to myself,

I’m going to photograph stones, and, of course, they didn’t end up interesting me. You have to become surprised and then become surprised again with the photographs in order to edit them afterward. It’s difficult. Sometimes, like Alvarez Bravo used to say—

I always talk about Alvarez Bravo, forgive me, but he’s like my guru—“Graciela, it’s just that the little shrews have already come,” the muses, right? So, I think it’s true, that all of a sudden there’s something that inspires you, and you begin to work. I’m the kind who photographs what I find. What comes my way. What falls from the sky.

Ramón Reverté is the editor in chief and creative director of Editorial RM, a publishing house based in Mexico and Spain.

Translated from the Spanish by Elianna Kan.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Places

-

Words

WordsJohn Divola & Mark Ruwedel

Fall 2018 By Amanda Maddox -

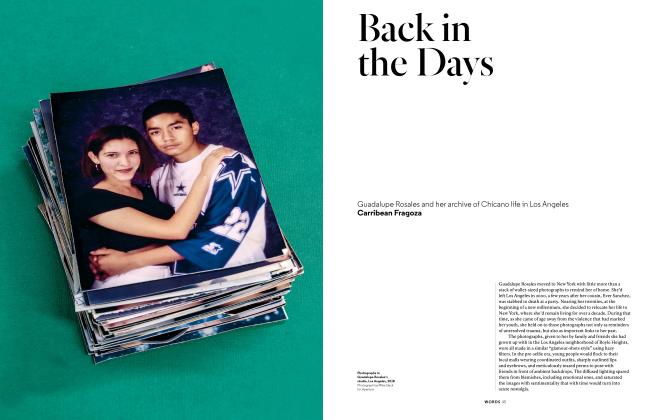

Words

WordsBack In The Days

Fall 2018 By Carribean Fragoza -

Pictures

PicturesRinko Kawauchi

Summer 2015 By Lesley A. Martin -

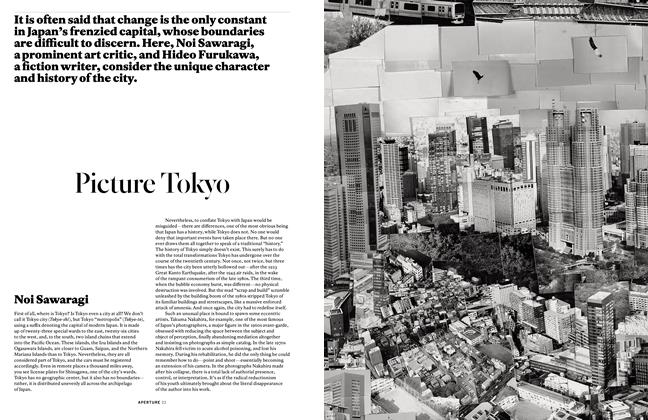

Words

WordsPicture Tokyo

Summer 2015 By Noi Sawaragi, Hideo Furukawa -

Pictures

PicturesKikuji Kawada

Summer 2015 By Ryuichi Kaneko -

Pictures

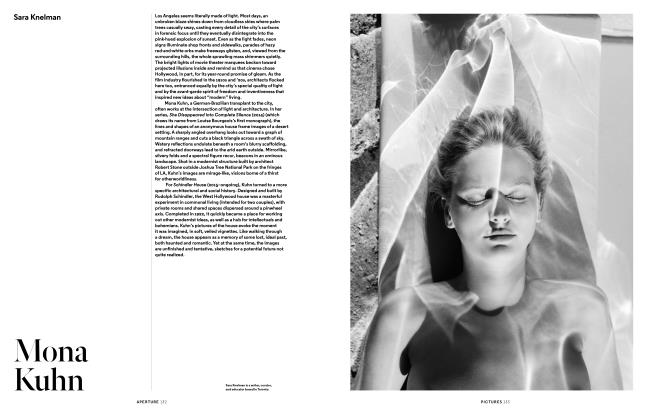

PicturesMona Kuhn

Fall 2018 By Sara Knelman