The Mug Shot A Brief History

Shawn Michelle Smith

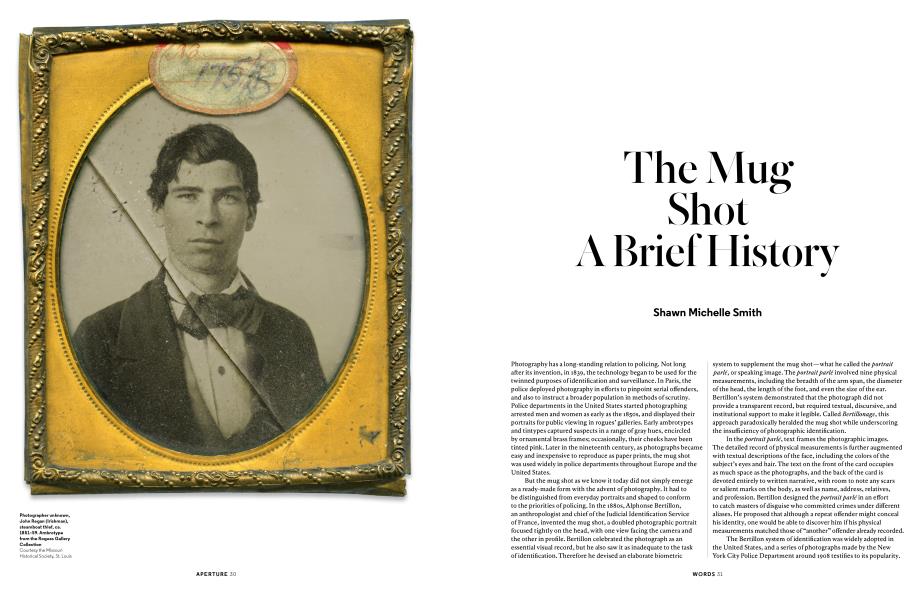

Photography has a long-standing relation to policing. Not long after its invention, in 1839, the technology began to be used for the twinned purposes of identification and surveillance. In Paris, the police deployed photography in efforts to pinpoint serial offenders, and also to instruct a broader population in methods of scrutiny. Police departments in the United States started photographing arrested men and women as early as the 1850s, and displayed their portraits for public viewing in rogues’ galleries. Early ambrotypes and tintypes captured suspects in a range of gray hues, encircled by ornamental brass frames; occasionally, their cheeks have been tinted pink. Later in the nineteenth century, as photographs became easy and inexpensive to reproduce as paper prints, the mug shot was used widely in police departments throughout Europe and the United States.

But the mug shot as we know it today did not simply emerge as a ready-made form with the advent of photography. It had to be distinguished from everyday portraits and shaped to conform to the priorities of policing. In the 1880s, Alphonse Bertillon, an anthropologist and chief of the Judicial Identification Service of France, invented the mug shot, a doubled photographic portrait focused tightly on the head, with one view facing the camera and the other in profile. Bertillon celebrated the photograph as an essential visual record, but he also saw it as inadequate to the task of identification. Therefore he devised an elaborate biometric system to supplement the mug shot—what he called the portrait parle, or speaking image. The portrait parle involved nine physical measurements, including the breadth of the arm span, the diameter of the head, the length of the foot, and even the size of the ear. Bertillon’s system demonstrated that the photograph did not provide a transparent record, but required textual, discursive, and institutional support to make it legible. Called Bertillonage, this approach paradoxically heralded the mug shot while underscoring the insufficiency of photographic identification.

In the portrait parle, text frames the photographic images.

The detailed record of physical measurements is further augmented with textual descriptions of the face, including the colors of the subject’s eyes and hair. The text on the front of the card occupies as much space as the photographs, and the back of the card is devoted entirely to written narrative, with room to note any scars or salient marks on the body, as well as name, address, relatives, and profession. Bertillon designed the portrait parle in an effort to catch masters of disguise who committed crimes under different aliases. He proposed that although a repeat offender might conceal his identity, one would be able to discover him if his physical measurements matched those of “another” offender already recorded.

The Bertillon system of identification was widely adopted in the United States, and a series of photographs made by the New York City Police Department around 1908 testifies to its popularity.

WORDS

Across the series, two white men, expertly framed and illuminated by flash, perform Bertillonage for the camera, demonstrating the technique and showing how each of the physical measurements should be made. One man, with a bushy mustache and short, slicked-back hair, plays the recording officer. He wears a bow tie and has carefully rolled up his shirtsleeves for the task at hand. His younger, slighter colleague plays the person under arrest.

In one striking image in the series, the man who plays the arrested subject looks directly at the camera as his counterpart presses close against him, stretching out his arms horizontally, to measure the man’s arm span. It is a notably intimate pose; the measurement requires the officer to extend his own body against the man under investigation. Such performative views show how an arrested individual is to be surveyed by the police, but they also imply a marked degree of compliance necessary on the part of the offender. Other images simulate people who refuse to sit for their mug shots and are wrestled into submission before the camera by multiple men, suggesting that not all subjects would be amenable to these extensive measurements.

Bertillonage is the epitome of an instrumentalized way of seeing, measuring, and recording the body. As such practices flourished, police stations in the United States also provided a parallel form of viewing for a broader public, the rogues’ gallery.

Mug shots were displayed for popular entertainment with the hope that public viewing would increase the number of investigative eyes on the ground. Another kind of popular rogues’ gallery was circulated in printed form: in 1886, Thomas Byrnes, chief detective of the New York City Police Department, published 204 photographs of legal offenders in his book Professional Criminals of America.

Byrnes departed from the strict form of Bertillonage in his published rogues’ gallery, presenting a single, numbered photograph of each subject, a notation of his or her multiple aliases, a physical description, and a detailed record of past crimes. For example, number 115, Ellen Clegg, alias Ellen Lee, also known as Mary Wilson, Mary Gray, and Mary Lane, is identified as a shoplifter, pickpocket, and handbag opener. Her photograph is described as “a pretty good one, taken in 1876,” and shows her turned slightly away from the camera, dressed in street clothes, including a coat and an elaborate hat. According to Byrnes, she weighs 145 pounds; stands five feet, five inches tall; and has brown hair, brown eyes, a light complexion, and large ears. The detective describes her as a clever woman, and an expert thief whose photograph graces several rogues’ galleries across the country. In his general discussion of pickpockets, Byrnes notes that they are not unusual in manner and dress and would not draw attention in a public place; Clegg’s photograph corroborates that statement. Professional Criminals of America subtly instructs readers to study the faces of the people it records, as well as those they encounter in daily life, encouraging viewers to be on the lookout for infamous repeat offenders.

One of the most notable aspects of Byrnes’s Professional Criminals of America is the apparent whiteness of its subjects.

None of the written descriptions paired with photographs identify men and women as “colored,” although at least one arresting officer is described as such. Instead, the text delineates different white ethnicities, including Irish, English, Scottish, German, and Jewish. Complexions are described as “florid,” “sallow,” “ruddy,” and “sandy,” and there are almost as many deemed “dark” as “light.”

But these are all considered different shades of white. Given the grossly disproportionate numbers of men and women of color incarcerated in the United States today, how might one understand the whiteness of the subjects represented in Byrnes’s 1886 text?

As Simone Browne has argued in Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (2015), beginning with slavery, the black body has been an object of surveillance in the United States, marked, literally and metaphorically, as property. Blackness is always already under scrutiny, while whiteness is defined by not being put on display; surveillance is a racialized optic. In this cultural context, the absence of men and women of color from Byrnes’s printed rogues’ gallery suggests that viewers did not need to learn to read the body of color since men and women of color were already under a racialized surveillance. The delineation of white subjects in Byrnes’s text suggests that viewers had to be trained and instructed to see white men and women as criminal and also to parse whiteness itself. Professional Criminals of America makes visible the notion of “variegated whiteness” that proliferated in the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Historian Matthew Frye Jacobson has discussed how, in response to increased European immigration, so-called Anglo-Saxon nativists sought to restrict the definition of “free white persons” eligible for naturalized citizenship according to the 1790 naturalization law. They did so by delineating a new hierarchy of “white races.”

Blackness is always already under scrutiny, while whiteness is defined by not being put on display; surveillance is a racialized optic.

In part, Byrnes’s text instructs viewers to distinguish Anglo-Saxons from “other” white races increasingly deemed suspect.

Today the mug shot remains a prevalent (paired) image, an instrumental photograph that continues to encourage popular practices of observation, inviting the public to police itself. What the history of the mug shot demonstrates is that such disciplinary ways of looking had to be learned; they were crafted, standardized, practiced, and taught. There is nothing transparent about these images or the way they present individuals, and despite their long legacy, their point of view can be challenged in order to generate alternative ways of seeing and representing incarcerated people.

Shawn Michelle Smith is Professor of Visual and Critical Studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the author of At the Edge of Sight: Photography and the Unseen (2013).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

WordsTruth & Reconciliation

Spring 2018 By Sarah Lewis -

Words

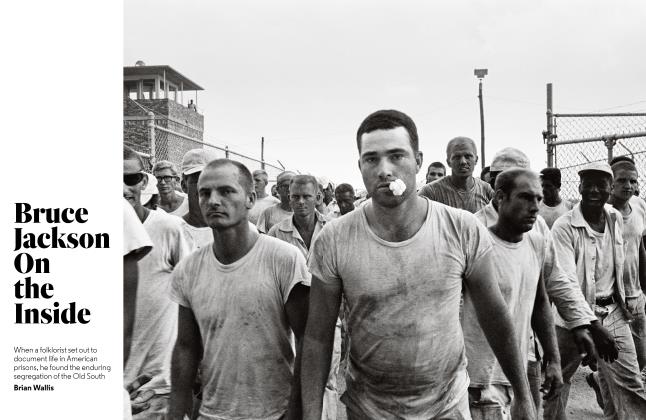

WordsBruce Jackson On The Inside

Spring 2018 By Brian Wallis -

Pictures

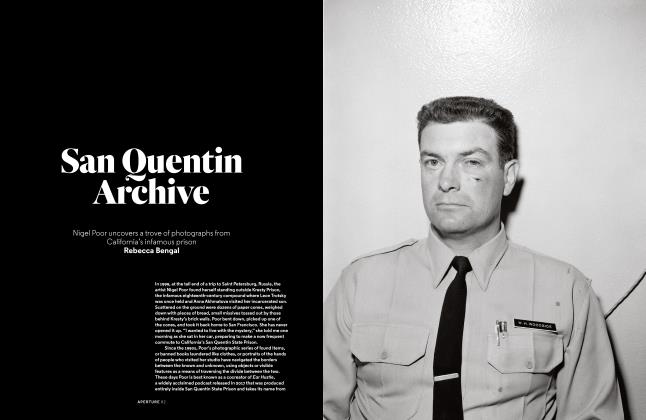

PicturesSan Quentin Archive

Spring 2018 By Rebecca Bengal -

Pictures

PicturesDeborah Luster

Spring 2018 By Zachary Lazar -

Pictures

PicturesStephen Tourlentes

Spring 2018 By Mabel O. Wilson -

Pictures

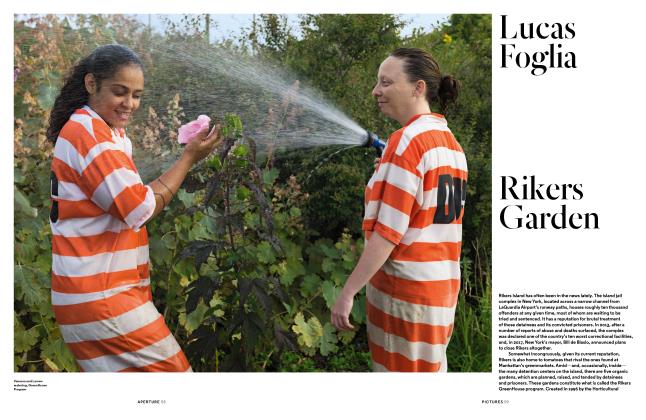

PicturesLucas Foglia

Spring 2018 By Jordan Kisner

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Words

-

Words

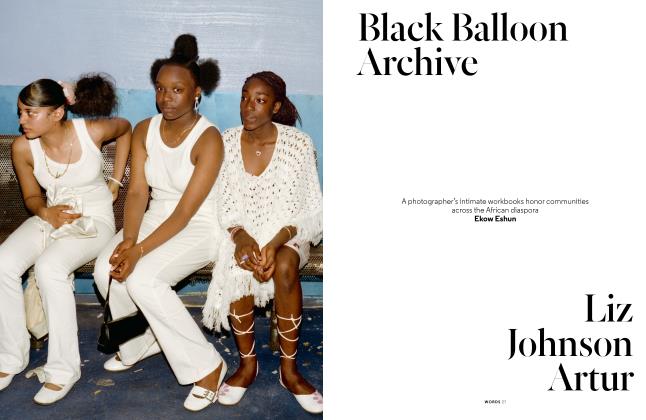

WordsBlack Balloon Archive Liz Johnson Artur

Winter 2018 By Ekow Eshun -

Words

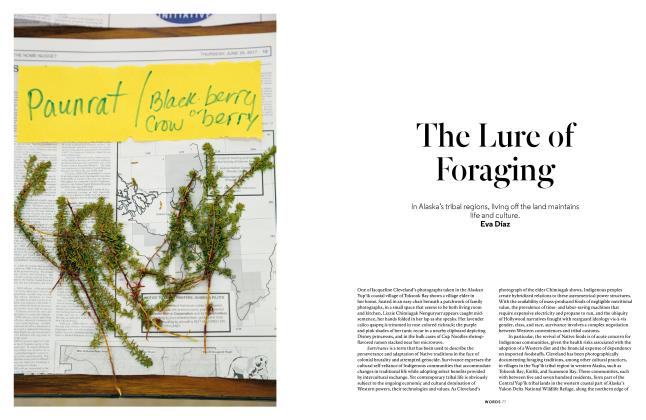

WordsThe Lure Of Foraging

Fall 2020 By Eva Díaz -

Words

WordsThe Feminist Avant-Garde

Winter 2016 By Nancy Princenthal -

Essay

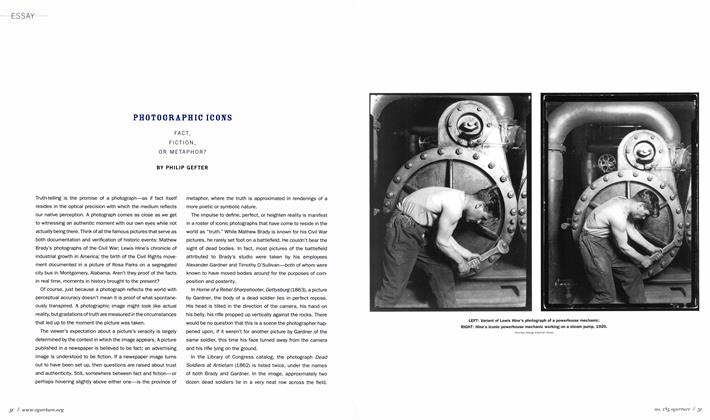

EssayPhotographic Icons

Winter 2006 By Philip Gefter -

Words

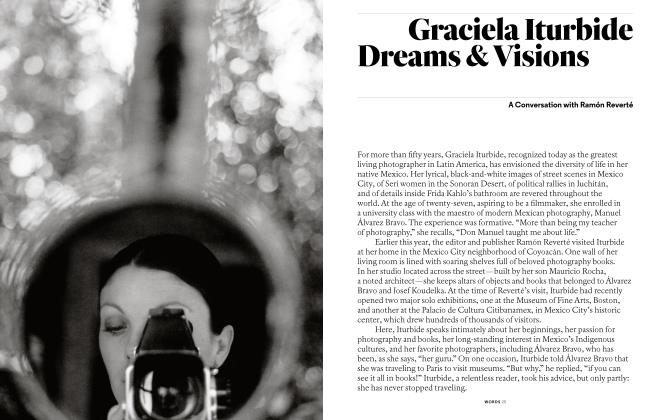

WordsGraciela Iturbide: Dreams & Visions

Fall 2019 By Ramón Reverté -

Words

WordsTruth Telling & High Fashion

Summer 2017 By Rita Potenza