Joseph Rodriguez

Reginald Dwayne Betts

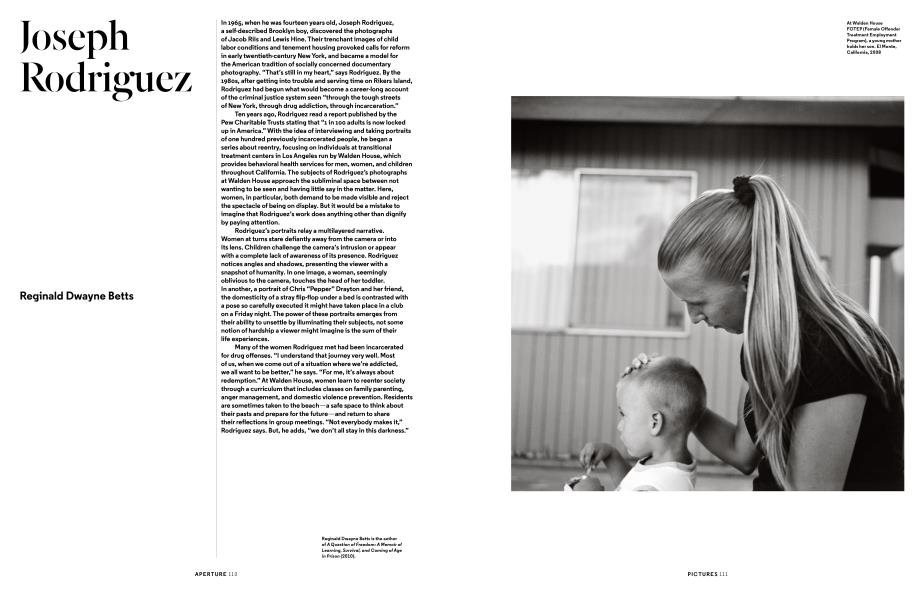

In 1965, when he was fourteen years old, Joseph Rodriguez, a self-described Brooklyn boy, discovered the photographs of Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine. Their trenchant images of child labor conditions and tenement housing provoked calls for reform in early twentieth-century New York, and became a model for the American tradition of socially concerned documentary photography. "That’s still in my heart,” says Rodriguez. By the 1980s, after getting into trouble and serving time on Rikers Island, Rodriguez had begun what would become a career-long account of the criminal justice system seen "through the tough streets of New York, through drug addiction, through incarceration.”

Ten years ago, Rodriguez read a report published by the Pew Charitable Trusts stating that "1 in 100 adults is now locked up in America.” With the idea of interviewing and taking portraits of one hundred previously incarcerated people, he began a series about reentry, focusing on individuals at transitional treatment centers in Los Angeles run by Walden House, which provides behavioral health services for men, women, and children throughout California. The subjects of Rodriguez’s photographs at Walden House approach the subliminal space between not wanting to be seen and having little say in the matter. Here, women, in particular, both demand to be made visible and reject the spectacle of being on display. But it would be a mistake to imagine that Rodriguez’s work does anything other than dignify by paying attention.

Rodriguez’s portraits relay a multilayered narrative.

Women at turns stare defiantly away from the camera or into its lens. Children challenge the camera’s intrusion or appear with a complete lack of awareness of its presence. Rodriguez notices angles and shadows, presenting the viewer with a snapshot of humanity. In one image, a woman, seemingly oblivious to the camera, touches the head of her toddler.

In another, a portrait of Chris "Pepper” Drayton and her friend, the domesticity of a stray flip-flop under a bed is contrasted with a pose so carefully executed it might have taken place in a club on a Friday night. The power of these portraits emerges from their ability to unsettle by illuminating their subjects, not some notion of hardship a viewer might imagine is the sum of their life experiences.

Many of the women Rodriguez met had been incarcerated for drug offenses. "I understand that journey very well. Most of us, when we come out of a situation where we’re addicted, we all want to be better,” he says. "For me, it’s always about redemption.” At Walden House, women learn to reenter society through a curriculum that includes classes on family parenting, anger management, and domestic violence prevention. Residents are sometimes taken to the beach—a safe space to think about their pasts and prepare for the future—and return to share their reflections in group meetings. "Not everybody makes it,” Rodriguez says. But, he adds, "we don’t all stay in this darkness.”

Reginald Dwayne Betts is the author of A Question of Freedom: A Memoir of Learning, Survival, and Coming of Age in Prison (2010).

PICTURES

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

WordsTruth & Reconciliation

Spring 2018 By Sarah Lewis -

Words

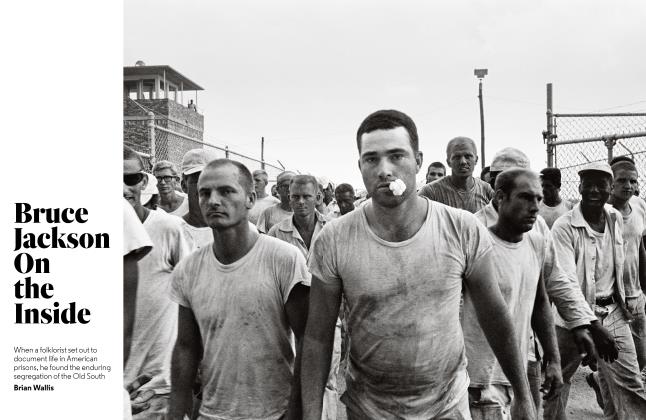

WordsBruce Jackson On The Inside

Spring 2018 By Brian Wallis -

Pictures

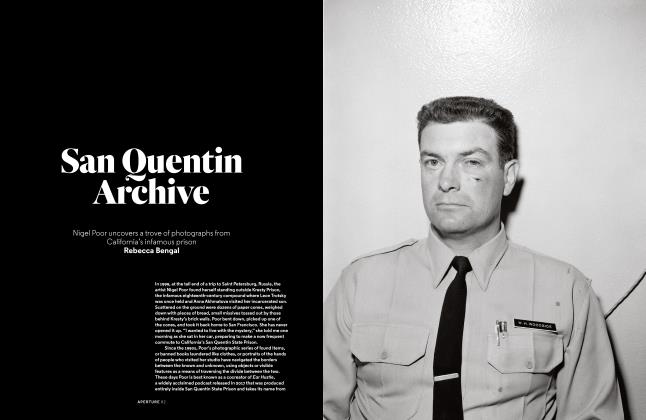

PicturesSan Quentin Archive

Spring 2018 By Rebecca Bengal -

Pictures

PicturesDeborah Luster

Spring 2018 By Zachary Lazar -

Pictures

PicturesStephen Tourlentes

Spring 2018 By Mabel O. Wilson -

Pictures

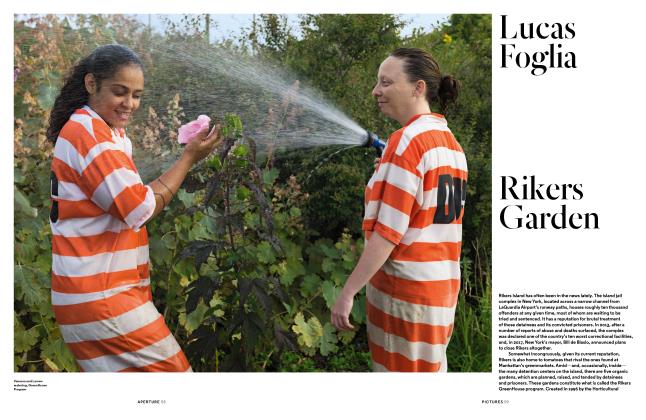

PicturesLucas Foglia

Spring 2018 By Jordan Kisner

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Pictures

-

Pictures

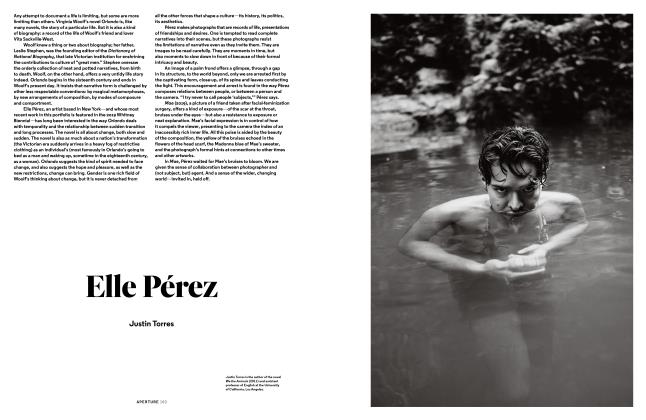

PicturesElle Pérez

Summer 2019 -

Pictures

PicturesJosephine Pryde

Winter 2016 By Alex Klein -

Pictures

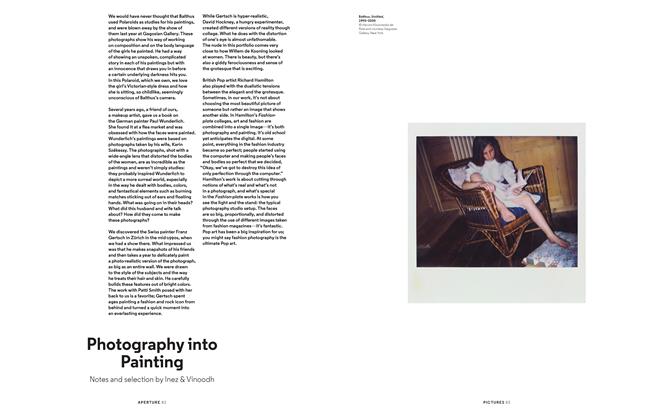

PicturesPhotography Into Painting

Fall 2014 By Inez -

Pictures

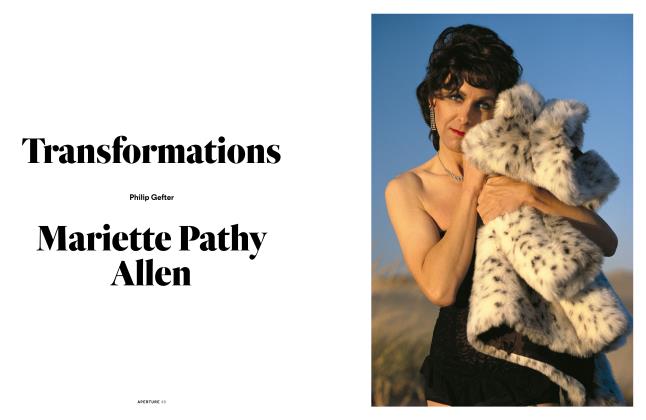

PicturesTransformations: Mariette Pathy Allen

Winter 2017 By Philip Gefter -

Pictures

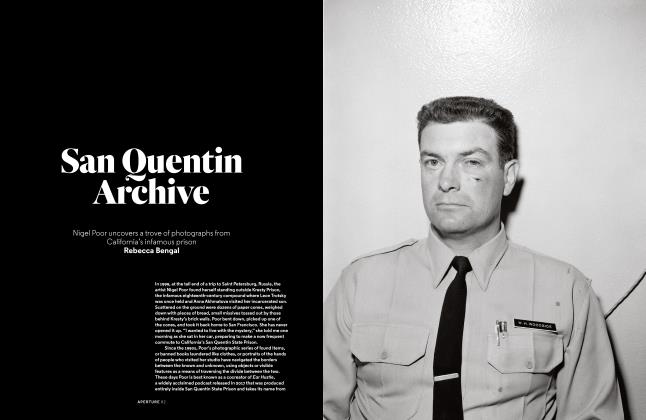

PicturesSan Quentin Archive

Spring 2018 By Rebecca Bengal -

Pictures

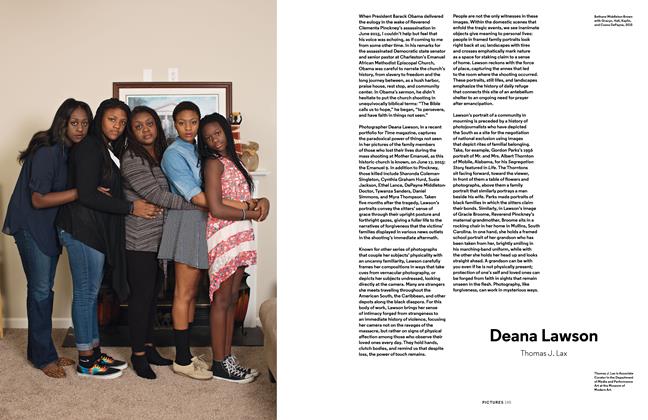

PicturesDeana Lawson

Summer 2016 By Thomas J. Lax