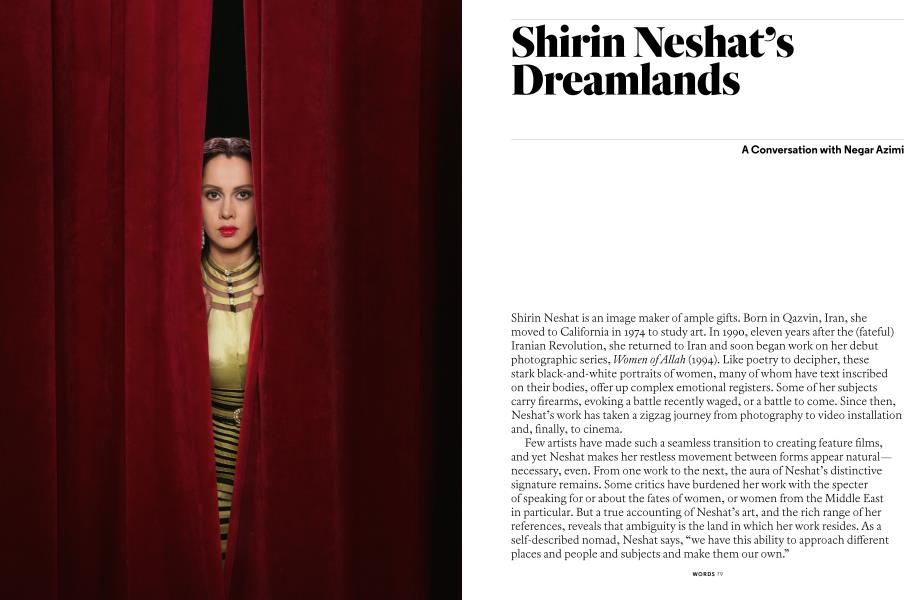

Shirin Neshat’s Dreamlands

Negar Azimi

Shirin Neshat is an image maker of ample gifts. Born in Qazvin, Iran, she moved to California in 1974 to study art. In 1990, eleven years after the (fateful) Iranian Revolution, she returned to Iran and soon began work on her debut photographic series, Women of Allah (1994). Like poetry to decipher, these stark black-and-white portraits of women, many of whom have text inscribed on their bodies, offer up complex emotional registers. Some of her subjects carry firearms, evoking a battle recently waged, or a battle to come. Since then, Neshat’s work has taken a zigzag journey from photography to video installation and, finally, to cinema.

Few artists have made such a seamless transition to creating feature films, and yet Neshat makes her restless movement between forms appear natural— necessary, even. From one work to the next, the aura of Neshat’s distinctive signature remains. Some critics have burdened her work with the specter of speaking for or about the fates of women, or women from the Middle East in particular. But a true accounting of Neshat’s art, and the rich range of her references, reveals that ambiguity is the land in which her work resides. As a self-described nomad, Neshat says, “we have this ability to approach different places and people and subjects and make them our own.”

WORDS

Negar Azimi: Shirin, as an artist you’ve brought images into the world that are burned into the mind. They’re literally stuck—certainly in my own. They’re images of such iconicity, of such jaw-dropping beauty and enigma. I’m thinking, for example, of the stark juxtaposition of the male and the female singer in Turbulent (1998). Or Rapture (1999), in which you see women marching defiantly into a murky sea. Your gift for composition is significant, and you’ve created a visual vocabulary that I think is all your own. Where do these images come from?

Shirin Neshat: I think that at root I’m an image maker and the images I’m drawn to are paradoxical, full of contradictions. Perhaps the only way I can explain it is that this is how I feel about everything around me. I feel like Fm full of contradictions, life is full of contradictions, and there’s a good and bad in everything. I never see anything in between.

NA: Your images are emotionally potent, but ambiguous too. Those women marching into the sea—are they running away from something? Or are they walking into the sea because they want to? Is the woman in the unforgettable first scene of Women Without Men (2009) flying, or is she in fact falling? That ambiguity is part of the power of your visual language.

You made an evolution from being a still photographer to authoring filmic videos and video installations. Now you make cinema. First, can you tell me a little about how you came to be a photographer?

SN: I guess I’ve become very good at building a profession out of things that I’ve never studied or had formal training in. This doesn’t mean that I’m naturally talented at any of them! But I do have a tendency to experiment. When I was making the series Women of Allah, I was not a photographer, but I was really struck by the power of the photojournalism that had documented the Iranian Revolution. No painting, sculpture, movie could have captured the spirit of the religious fervor.

Then, slowly, I moved from making images that had this borderline photojournalistic approach to storytelling, but without really knowing how to do it. I think the video installations in some ways prepared me. Videos like Rapture or Turbulent were like moving photographs; there was no real logic of filmmaking to them. Slowly, I had a protagonist. Then I had a beginning, middle, and end. There was a real director behind the vision. Over time, my work became more cinematic, and I felt like trying to tell a story rather than just create an environment. That led to my first entry into filmmaking, which was Women Without Men.

NA: You note that images of the Iranian Revolution of 1979 were consequential, and somehow led you to the medium of photography. I immediately conjure Abbas’s haunting photographs of the revolution and its aftermaths, and Bahman Jalali’s too. But outside of that moment, what was your visual coming of age like? What marked or influenced you?

SN: Most of my young adulthood was spent in the United States, so my education was very much Western. I was away from Iran for so long, and was out of touch with what was happening there culturally. I was most influenced by American or European photographers, and Western art history. Later, I started to go to Iran. I was curious about the revolution and the changes taking place in my family. I spent a lot of time speaking to friends who had become involved with the revolution. But I wasn’t really in dialogue with artists. My family wasn’t really artistic.

When I came back to the United States, I worked at the Storefront for Art and Architecture, and I was around people like Kiki Smith, Mel Chin, Vito Acconci, and David Hammons. My mind and life were divided, literally, between the bohemia of New York and what was going on politically in Iran.

Later, my life changed again. I now had an Iranian partner, my collaborators became Iranian, and I studied Iranian cinema.

I began to see the similarities and differences between how I made sense of the revolution and its legacies, and how those who had lived in Iran made sense of it all. I saw a vast difference. I have a more diasporic or exilic ... a kind of accented point of view. And a very Western, absolutely conceptual approach—never, ever to do with realism. So what I’m trying to say is that my New York life had everything to do with the evolution of my ideas. My subjects were Iranian, but I was never really inspired or influenced by Iranian artists.

Regardless of how many years I’ve lived here, certain American people and places make me feel like a foreigner.

NA: The question of influence is endlessly interesting. At the moment Pm thinking about the late avant-garde theater director Reza Abdoh, who was also of Iranian American background. And not unlike with your own work, there are many competing claims on his. Some say that his work was influenced by aspects of Shia Islam, like the Ta’ziyeh passion play. Others look at it through the lens of Artaud and his theater of cruelty. And yet others argue that it’s just deeply American, more informed by American TV than anything else. So the question is, can it be all of these things? Can one’s work be a collage, especially for someone like you with, as you said, an exilic background, a sort of pastiche of influences?

SN: Influence is such a mystery. I do believe there are elements in my work that have to do with my experience as a kid in Iran. I left when I was seventeen. But I feel like that Iranian part of me has deeply informed my work nonetheless, even though I’m very American too.

NA: Your new project bridges these two worlds. The last time I saw you, I’d recently come back from Marfa, Texas. You asked me if the landscape in Texas reminded me of Iran, to which I said I hadn’t even thought of that. Which then led to a discussion about your work-in-progress, Dreamland, which centers on a young Iranian photographer and a sort of shape-shifting, enigmatic Midwestern desert context. Can you tell me a little more about how this project came to be?

SN: I’ve finally found a way to explore my experience as an Iranian in America. I find it fascinating that, regardless of how many years I’ve lived here, certain American people and places make me feel like a foreigner. I settled on working around a hypothetical Midwestern town. I wanted to explore people who might feel completely alienated from each other. In this case, I will have an Iranian female protagonist who works for the Census Bureau. She has access to the all-white American members of this town, and develops a curiosity and obsession about the “other,” and begins photographing them.

NA: Tell me about the setting.

SN: It’s a desert landscape, a typical rural town, and then there’s this kind of Iranian landscape too—an Iranian colony with Iranians living behind these walls some distance away. So it’s not completely realistic.

NA: There was a line in the short resume of the project I read in which the Iranian village is described as “something between a refugee camp, a hospital, or a prison.” That really struck me, and it brings to mind the current moment, for rather obvious reasons.

SN: The idea began with Trump, of course, just as people started saying things like, “Oh my God, they’re going to make a colony for Muslims, and they’re going to assign them numbers,” and so on. It’s very futuristic, even bleak, in that sense. But I also thought a lot about 77ze House Is Black, the 1962 film about a leper colony by Forough Farrokhzad, the Iranian filmmaker-poet. I thought that the colony could be rather surrealistic, whereas the town in America would be realistic.

NA: Surrealism and allegory are very much present in your work. What does Surrealism or the surreal offer to you as a tool?

SN: I tend to gravitate toward poetry and literature that is magical realist. For example, in Women Without Men, the women live in this surreal orchard. They create their own society, like a place of exile, perhaps not unlike my own. I was also interested in gardens as a surreal space. Gardens are very present in Islamic and Persian mythology and literature and poetry and mysticism. They are places where we feel completely free, where we can be ourselves.

In this new film, the colony could be another sort of allegorical space. It could be a refugee camp, but it could be also a little paradise. It could be a political space. It could be a kind of mental asylum.

NA: You’re working on Dreamland with a cinema legend, Jean-Claude Carriere, the screenwriter of Luis Bunuel’s late films. What’s the process been like?

SN: I love the surrealism and absurdity of Bunuel’s work. One of the scenes in Women Without Men, when the army comes to the orchard and has a lavish feast, was inspired by The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972). As for Jean-Claude, I worked with him a little bit on the last film, Looking for Oum Kulthum (2017). Some things are directly drawn from his imagination. I really like him, the way he thinks, the way he brings absurdity and dark comedy into his art.

NA: I know Dreamland is still at the ideas stage, but I looked at some of your reference images. They reminded me of the searing Depression-era photographs of Walker Evans, among other things. You said you have a photographer’s mind, and I can’t help but notice that so many of your movingimage works have powerful still images within them. Can you tell me how you storyboard things? Do you collect images and put them on a bulletin board? Do you build narratives around certain images?

SN: You know, I have a master of fine arts and I can’t even draw! I’ve never been able to sketch out an idea. So the only way I could communicate with my colleagues and collaborators about mood or space or the evolution of a story is through researching images from other people’s work and then creating my own storyboards. For example, I’ve looked at a lot of Man Ray’s films and photography. I’ve been interested in photographers who are filmmakers, and photographers who use simple techniques, like placing glass over the camera to make an image slightly blurry, or infrared, like Jean Cocteau or Bunuel. We did that with Darius Khondji, the great cinematographer, who worked with me on the Illusions & Mirrors (2013), which was followed by two other videos called Dreamers (2013-16). Every one of the videos used the same visual logic and was inspired by Surrealist filmmakers. It was almost like I picked up where they left off. These days, Mary Ellen Mark’s photographs have been hugely inspirational to me for the Dreamland project. And beyond photographers like Walker Evans or Mark, I learned tremendously from the movie Nebraska (2013) by Alexander Payne.

On the other hand, when I’m doing research around the Iranian colony, I go back to Iranian films. I go to images of young people in prison, or mental hospitals, too. I go to Forough’s film, The House Is Black. Storyboarding in this way is essential.

NA: That’s a very generous way of talking about your work: that you’re a product of everything that you’ve seen, in a way. That we all are. It gives lie to the myth of the self-contained genius.

SN: Exactly. I think every artist brings forward the influences of other artists. It’s like paying tribute.

NA: I want to shift to the cinematography in Women Without Men, which is really extraordinary. Many of the scenes are, for lack of a better term, painterly.

SN: My cinematographer is Martin Gschlacht, who also shot Looking for Oum Kulthum. We worked very closely together, frame by frame.

I think every artist brings forward the influences of other artists. It’s like paying tribute.

I’m a true hybrid. I’m a nomad. I don’t see the same boundaries others do.

NA: I was interested in the way you captured the brothel in particular. Did you look at the late Iranian photographer Kaveh Golestan’s images of the slum of Shahr-e No, by chance? What other image universes did you dip into?

SN: We did look at Golestan’s images, in fact, from his series Prostitute (1975-77). We studied the images that were hung on the walls of the prostitutes’ places of work, the furniture, everything. His photography really informed our production design. The film takes place in 1953, when Shahr-e No actually existed. As you know, it was where many prostitutes gathered and lived. We also looked at the history of orientalist painting, especially in creating the scenes in the hammam. For the scenes involving the coup d’etat of 1953, we went to BBC photography archives of protests during the Mossadegh overthrow. We looked closely at the hired thugs pretending like they were actually pro-shah.

NA: You started working on Women Without Men in 2003, but it came out in 2009. Between those two dates, Iran experienced the biggest demonstrations it had seen since the revolution of 1979, under the banner of the Green Movement. Of course, many of us experienced these protests from afar, through shaky camera-phone images. The world won’t forget the young protester named Neda Agha-Soltan who was shot, fell to the earth, and bled to death on camera for all to see. Art was really meeting life in a powerful way when your film about another set of fateful protests in Iran came out the next year.

SN: It was such a coincidence. I think the 1953 coup was the most important, most pivotal political event before the Iranian Revolution. It was the last time the country had seen so many people calling for democracy, and the exit of the British, and all of that. History repeated itself. Unfortunately, both times, the people lost.

NA: Lookingfor Oum Kulthum took so many different shapes and forms over time. Like the best films, it had its own journey. It ultimately became a film about the making of a film.

I wonder how you came to that meta place, of meditating on the act of filmmaking itself.

SN: Well, like the director character in the film, I initially thought of making a biopic about the singer Oum Kulthum, because she’s such a fascinating woman. But after a few years of writing many drafts of scripts, we shifted direction, partially because biopics can often be quite boring. But also, as non-Egyptian, non-Arabs making a film about an Arab icon, many interesting questions came up. I think Jean-Claude was one of the first people who looked at me and said: “Look, you have to forget this biopic. Bring this film to the present day. Ask yourself why this film should be contemporary. What is your relationship to this film? What is your obsession?”

And slowly, we started to bring a contemporary element into the film, and then everyone else said to me: “Listen, you’ve got to really ask yourself, why have you, as an artist, a woman from Iran, developed such an obsession around this singer? What is it?

Is it her art? Is it her life? Is it her career? Does she remind you of some of your own challenges? Do you idealize her in a way that you wish you were like her?” So basically, “Take the script and work for yourself, and then come back to us.” That’s what I did.

NA: In some ways, the film is about limitation or impossibility: you as an Iranian treating an Arab icon. The superlative Arab icon. Technically, you couldn’t even shoot in Egypt, and settled on Morocco instead. But then again, the film is also about a sort of transcendence, I found. It made me think about how when I was growing up, my father, an Iranian man who doesn’t at all speak Spanish, loved the Gipsy Kings. He knew all the words to all the songs, because he sang phonetically. He owns those songs. In the same way, you could say Oum Kulthum belongs to all of us. That’s a very authentic experience—of knowing and not knowing at once.

SN: Absolutely. I’m a true hybrid—in my education, in my looks, everything. I’m a nomad. I don’t belong anywhere. There’s a mixed blessing in how we’re constructed, how our minds approach things. On the one hand, we don’t have one place that we can call home, but we also have this ability to approach different places and people and subjects and make them our own. I don’t even know how to think local.

I don’t see the same boundaries others do. Sometimes I hear, “Hey! You crossed the boundary.” Other people are always building boundaries around me, saying, “You’re a visual artist. You shouldn’t make film.” Or, “You’re Iranian. You shouldn’t touch an Arabic icon.” But I don’t think that way.

Negar Azimi is a senior editor of Bidoun.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

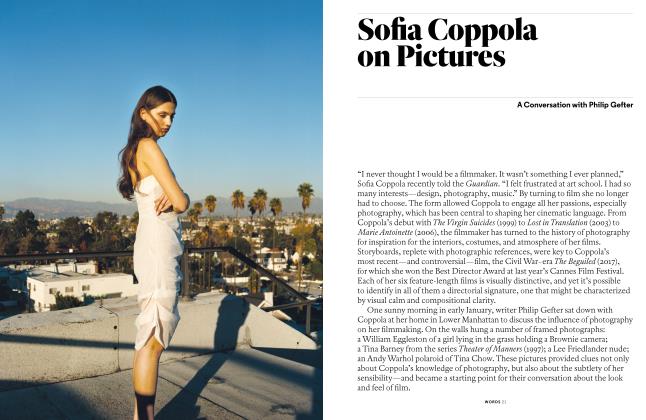

WordsSofia Coppola On Pictures

Summer 2018 By Philip Gefter -

Words

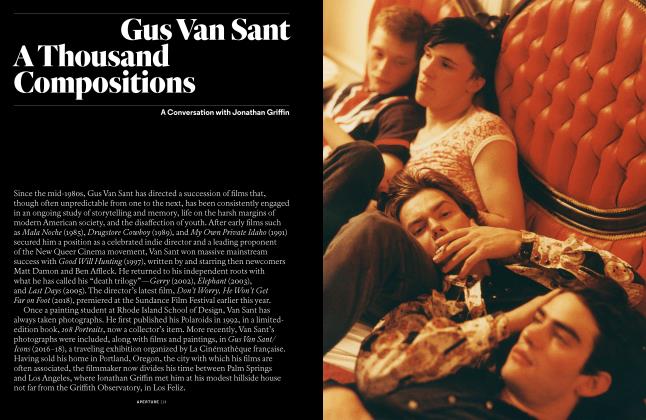

WordsGus Van Sant A Thousand Compositions

Summer 2018 By Jonathan Griffin -

Pictures

PicturesAlex Prager

Summer 2018 By Rebecca Bengal -

Words

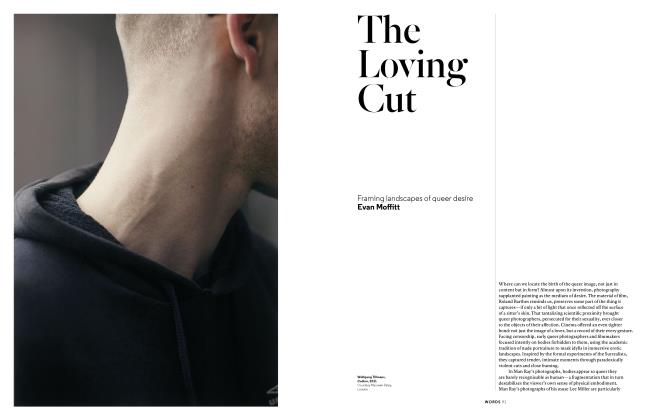

WordsThe Loving Cut

Summer 2018 By Evan Moffitt -

Words

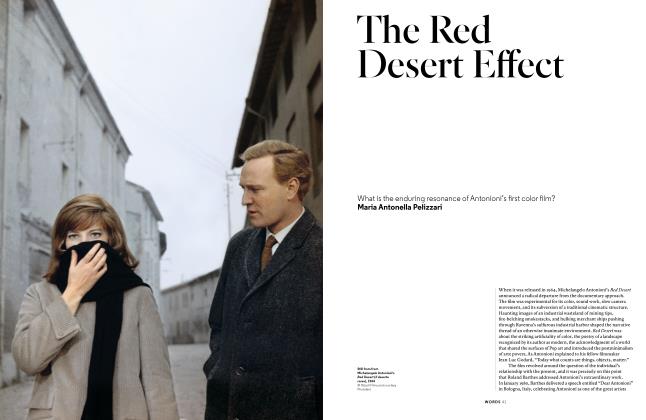

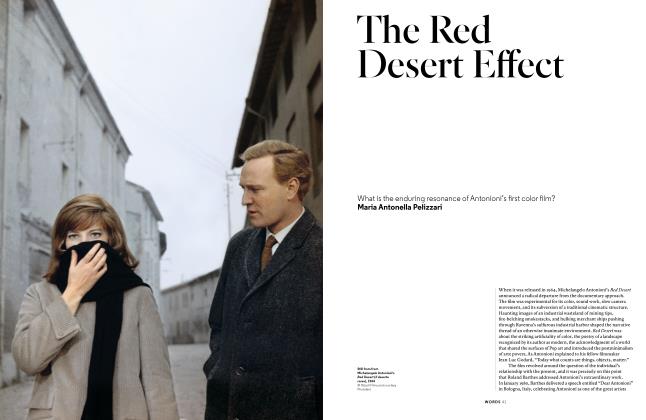

WordsThe Red Desert Effect

Summer 2018 By Maria Antonella Pelizzari -

Pictures

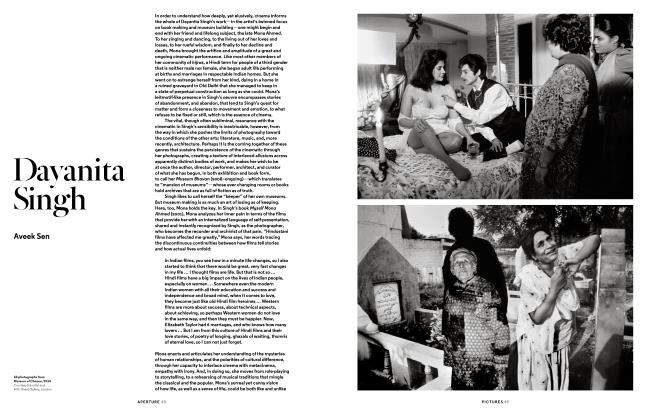

PicturesDayanita Singh

Summer 2018 By Aveek Sen

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Negar Azimi

Words

-

Words

WordsWords

Spring 2016 -

Words

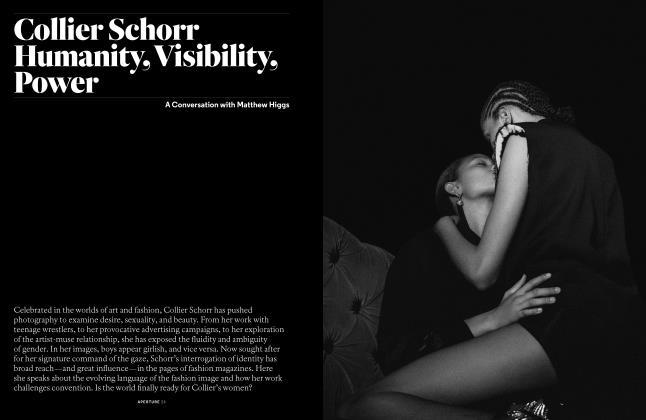

WordsCollier Schorr Humanity, Visibility, Power

Fall 2017 -

Words

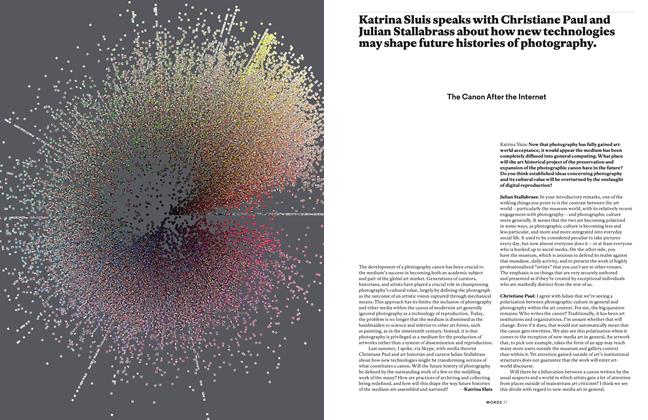

WordsThe Canon After The Internet

Winter 2013 By Katrina Sluis -

Words

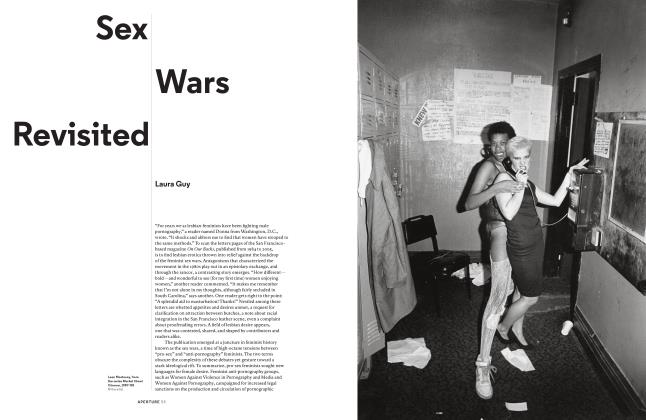

WordsSex Wars Revisited

Winter 2016 By Laura Guy -

Words

WordsThe Red Desert Effect

Summer 2018 By Maria Antonella Pelizzari -

Words

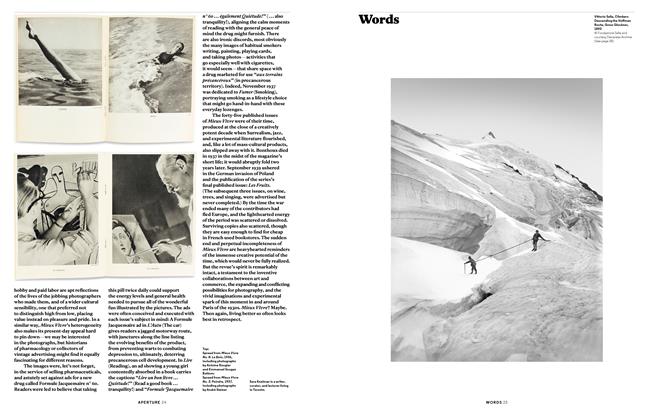

WordsSmoke Screen

Summer 2018 By Noam M. Elcott