Words

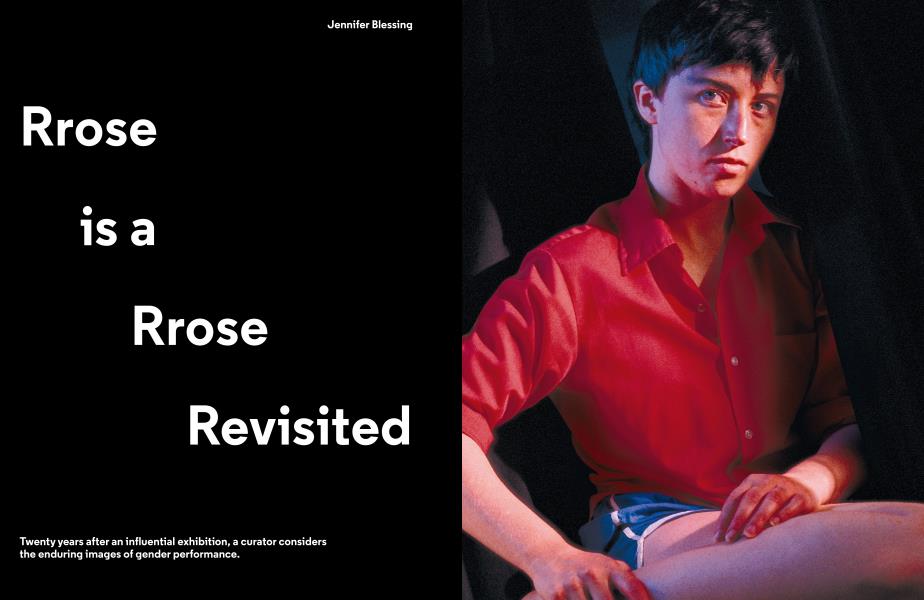

Rrose Is A Rrose Revisited

Twenty years after an influential exhibition, a curator considers the enduring images of gender performance.

Winter 2017 Jennifer BlessingRrose is a Rrose Revisited

Jennifer Blessing

Twenty years after an influential exhibition, a curator considers the enduring images of gender performance.

Gender and sexuality are multivalent, a spectrum of intersecting identities.

This year is the twentieth anniversary of Rrose is a Rrose is a Rrose: Gender Performance in Photography. In 1995, an exhibition proposal I submitted to the National Endowment for the Arts received one of the last exhibition grants to be awarded before the NEA was gutted by right-wing Republicans as part of the culture wars of the late 1980s and early ’90s. Two years later, in 1997, the exhibition opened in New York at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, and then traveled to the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh.

On the cover of its catalog is the gender-bending Surrealist artist and writer Claude Cahun.

The title, Rrose is a Rrose is a Rrose, combines the first name of Marcel Duchamp’s feminine alter ego, Rrose Selavy, whose name plays on the French phrase “Eros, c’est le vie” (Eros, that’s life), with Gertrude Stein’s poetic “motto,” in order to queer Duchamp’s Dada gesture. As telegraphed through its subtitle, Gender Performance in Photography, the exhibition was inspired in part by Judith Butler’s thinking about gender; the deconstruction of femininity by Pictures Generation artists, especially Cindy Sherman; the rediscovery of Cahun and Frida Kahlo; and Madonna’s and Grace Jones’s representations of phallic womanhood.

While I was eager to introduce lesser-known artists to a broader public, and historically contextualize contemporary art, two decades ago I was also on a mission of intellectual activism.

For me, at that time, theories of masquerade and lesbian spectatorship, along with drag performance, offered ways to elude the heterosexist, patriarchal male gaze and speak to more diverse desires. I was acutely aware of the many forms that “passing” took in my daily life, both professionally and personally, primarily in terms of gender and sexuality, but also surrounding class and ethnicity. I have no doubt now that this experience informed my interest in gender politics and the appeal of photographs that deal with gender expression.

The central premises of the show were as follows: tf//gender presentation is drag; there are no binaries (male/female, masculine/ feminine); gender and sexuality are multivalent, a spectrum of intersecting identities; and photography is an alluring vehicle with which to fix one’s pleasure in a certain kind of self-image. I was not interested in raw forms of disclosure or in the naked body as a “tell,” or unmasking. Rather, my interest lay in the glamour and idealism of studio photography; in portraiture as a collaborative process, a performance for the camera where the direct address of the subject looking at the camera/photographer/viewer articulates a distinct kind of power; and, finally, in the 1990s, fascination with photographic explorations of gender that could be historically situated in relation to earlier twentieth-century moments, specifically the interwar years and the 1970s.

Rrose featured ninety-five photographically based artworks— portraits, self-portraits, and photomontages—by twenty-four artists, in which the gender identity of a depicted subject is highlighted through performance for the camera, as well as through technical manipulation of the image. While some works use photography’s aura of realism and objectivity to promote fantasies of gender transformation, others use it to articulate the seeming incongruence between body and costume.

The exhibition was divided into two historical sections.

The first galleries featured photography created in the period between the two world wars, from Man Ray’s portrait Marcel Duchamp as Rrose Selavy (1920-21) to works by other European and American artists who embraced the liberating goals of the Dada and Surrealist movements, namely Brassa'i, Cahun, George Platt Lynes, Hannah Hoch, Cecil Beaton, and Madame Yevonde.

The Surrealists’ creative explorations of love, the mechanics of desire, and the mysteries of human sexuality provided a fertile milieu for others interested in the multifarious manifestations of gender.

WORDS

In the days before the Internet, the Rrose catalog offered images and voices that were otherwise relatively hard to find.

A dearth of publicly available imagery from the immediate postwar period was followed by an explosion, after 1968, of photographic objects focusing on gender ambiguity. Examples of these works, created from the late 1960s to the time of the exhibition, and often inspired by earlier Surrealist investigations, were presented in adjoining galleries. The radical social changes initiated in the 1960s—especially the rise of feminism, gay rights, and unconventional notions of masculinity—prompted modifications in socially acceptable standards of gender presentation. The artists in this section included Jurgen Klauke, Katharina Sieverding, Annette Messager, Andy Warhol, Lucas Samaras, and Robert Mapplethorpe, as well as the late Surrealist Pierre Molinier, whose fetishistic work was poised at the juncture between the older artists working between the wars, and the generation of’68 who rediscovered him.

Contemporary artists in the 1990s were quite deliberately setting out to question and explore sexuality and gender. Some commented upon mass media by appropriating the formal and technological means of its representations. Others, inspired by lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender communities, asserted the visibility of individuals who have been marginalized by so-called mainstream society. These artists, whose work was featured in Rrose, included Cindy Sherman, Nan Goldin, Christian Marclay, Catherine Opie, Janine Antoni, Matthew Barney, Inez van Lamsweerde, Lyle Ashton Harris, and Yasumasa Morimura.

The exhibition itself had very little in the way of didactic labels. One entrance to the galleries had a brief introductory wall text similar to the paragraphs above, while the text at another entrance was simply devoted to a long passage from Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes, “I like, I don’t like,” about individual subjectivity defined via taste, as a metaphor for desire. Barthes’s words also appear as the frontispiece of the catalog, with Cindy Sherman’s Untitled #112 (1982) on the facing page. There were no descriptions of the pictures on view in the exhibition, or information about their makers, beyond individual wall labels listing the artist’s name plus the work’s title, date, and medium. This concision was a calculated attempt to avoid deterministic pronouns. My goal was for visitors to recognize themselves as complex desiring subjects, to acknowledge the polymorphousness of their desire in relation to the images. I wanted viewers to experience the delirious pleasures of ambiguity—and to find their own pleasure—rather than to tell them what to see.

The Rrose project was conceived within the context of the contemporaneous proliferation of films starring cross-dressed protagonists, advertisements featuring ambiguously sexed adolescents, and myriad media images reflecting the 1990s fascination with gender identity. By integrating images of hypermasculine and hyperfeminine subjects within the context of manifold queer and trans portraits, I hoped to show that what today might be called cisgender presentation is also a kind of masquerade. So it was with disappointment that I witnessed a certain pop superstar go through the exhibition, pointing to a succession of pictures and announcing, “This is a girl, and that’s a boy.” She was demonstrating her sophisticated ability to read the codes of gender and sexual identity, but I wished she didn’t have to name the sitters as either/or. It reminded me of the first time I published an essay, on Claude Cahun for a graduate school journal. I asked to be identified as J. Blessing, and the editor confirmed with me that I chose my initial because I did not want to use my gender-determinant first name. Nevertheless, I was outed as “she” in an author blurb, in what felt at the time as a refusal to respect my preference.

When I reread my Rrose essay, I see how I tried to juggle terminology, highlighting historical usage and adopting vocabulary from a variety of authors and discourses in an attempt to avoid fixity, and yet now some terms feel dated and others are almost slurs. Today trans visibility is far greater—witness mainstream media coverage like the famous 2014 Time magazine cover article “The Transgender Tipping Point,” featuring Laverne Cox. The word trans is inflected differently than it was in the mid-1990s, when Q+ was just being added to LGBT. Now, there are many more terms to describe trans experience, and acknowledgment of the differences in usage among communities; at the same time, it is not unusual for people to request the pronouns with which they prefer to be identified.

In the days before the Internet, the Rrose catalog offered images and voices that were otherwise relatively hard to find.

The recent revival of interest in the exhibition overlaps with the trans activism of a younger generation, concurrent with the zombie revivification of the culture wars. At the time that Judith (Jack) Halberstam wrote his contribution, “The Art of Gender: Bathrooms, Butches, and the Aesthetics of Female Masculinity,” he was writing from an academic context; twenty years later the gender policing he described has become a national issue. Lyle Ashton Harris’s visual essay drag racing (1997) looks fresher than ever today, addressing intersectional identity through the performative photographic collages he began making in the mid-1990s. He is currently mining his extensive personal archive to tell the story of the arts community he inhabited circa 1990, and the issues around AIDS activism and multiculturalism that artists and theorists were engaging at that time.

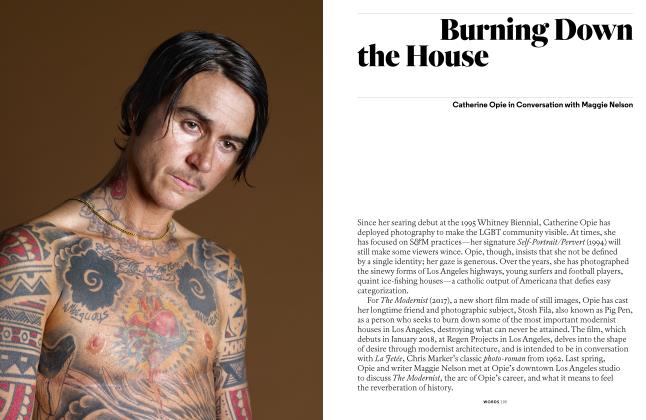

Ironically, Rrose would never have happened were it not for the support of the NEA. Because another grant application slated to be submitted by the Guggenheim couldn’t be finished in time for the agency’s deadline, I was given the opportunity to submit my idea for Rrose. The show’s long-term institutional impact can be found in the Guggenheim’s subsequent exhibitions and collecting: In 2008, the museum presented Catherine Opie:American Photographer. Photographs from Opie’s series Being and Having (1991), a witty send-up of the Lacanian notion of woman as phallus, were featured in both exhibitions. Her important early photograph Dyke (1993) and her three related works Self-Portrait/Cutting (1993), Seif-Portrait/Pervert (1994), and Seif-Portrait/Nursing (2004)—two of which appeared in Rrose—have been acquired by the museum, the only institution to have all four.

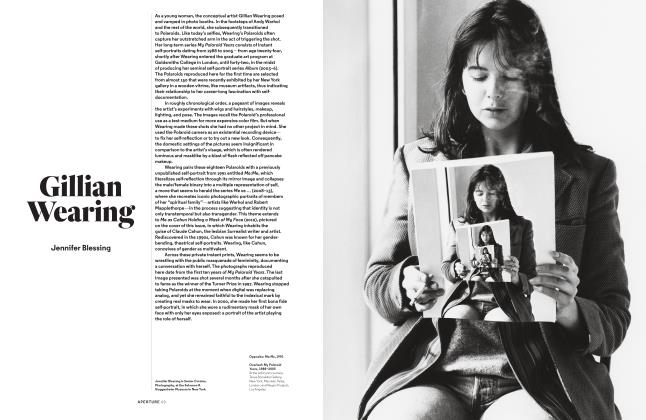

Opie’s Portraits series (1993-97), in which she portrayed her friends in the LGBT and leather communities in San Francisco— not in the pathos-laden, black-and-white reportage style typical of previous photographs of sexual subcultures, but in beautifully lit, gorgeous studio color—was a conscious bid to present them in a dignified and celebratory way. This utopian project of representing herself and her community in the manner in which they wanted to be presented, not privileging how others might want to see them, very much inspired what I hoped to achieve with Rrose, and also speaks, two decades later, to the appeal of the selfie as a form of self-empowerment, a way to locate agency in identity.

Ultimately, the gambit Rrose embodied—to provide a platform for voices that are often silenced and identities that are threatened with invisibility within hegemonic culture—has been fundamental to my practice as a curator, and is more important than ever today.

Jennifer Blessing is Senior Curator, Photography, at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

An early version of this essay was presented at the symposium “Untitled (Gender and Representation),” organized by Stephen Frailey and Joseph Maida at the School of Visual Arts, New York, in October 2016.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Pictures

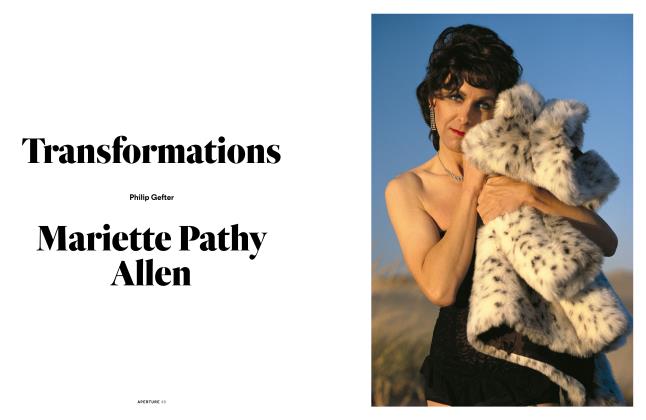

PicturesTransformations: Mariette Pathy Allen

Winter 2017 By Philip Gefter -

Pictures

PicturesNelson Morales

Winter 2017 By Lawrence La Fountain-Stokes -

Words

WordsGender Is A Playground

Winter 2017 -

Words

WordsBurning Down The House

Winter 2017 By Maggie Nelson -

Words

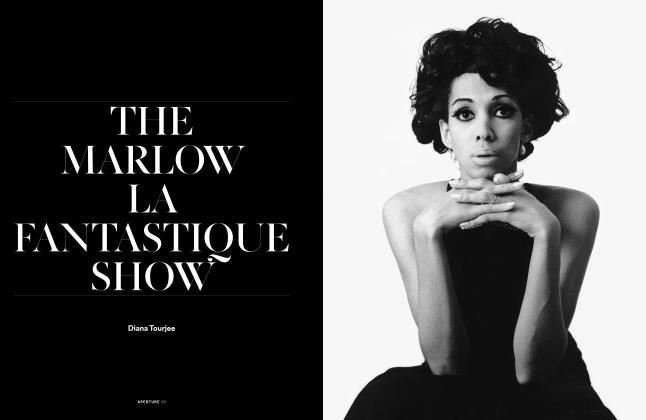

WordsThe Marlow: La Fantastioue Show

Winter 2017 By Diana Tourjee -

Pictures

PicturesJosué Azor Noctambules

Winter 2017 By Patrick Sylvain

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Jennifer Blessing

Words

-

Words

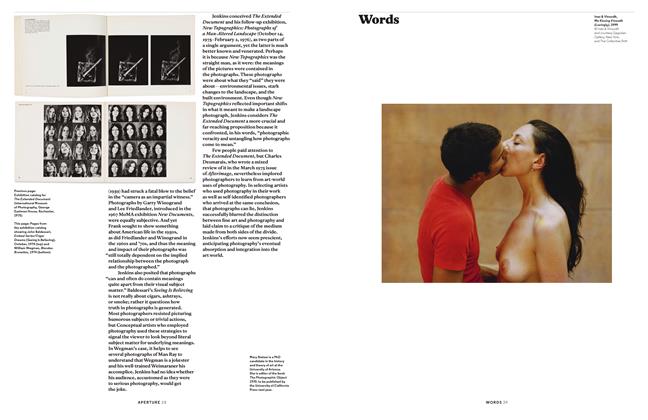

WordsWords

Fall 2014 -

Words

WordsRaw Material Company

Summer 2017 By Carole Diop -

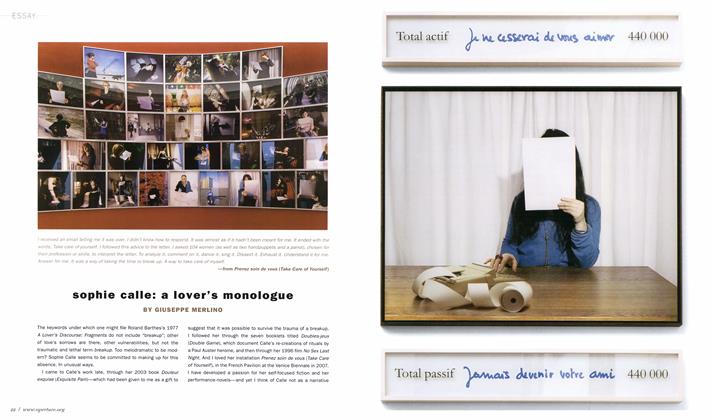

Essay

EssaySophie Calle: A Lover's Monologue

Summer 2008 By Giuseppe Merlino -

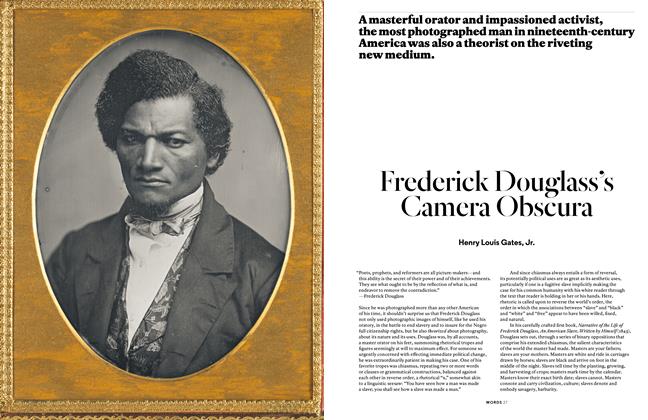

Words

WordsFrederick Douglass’s Camera Obscura

Summer 2016 By Henry Louis Gates -

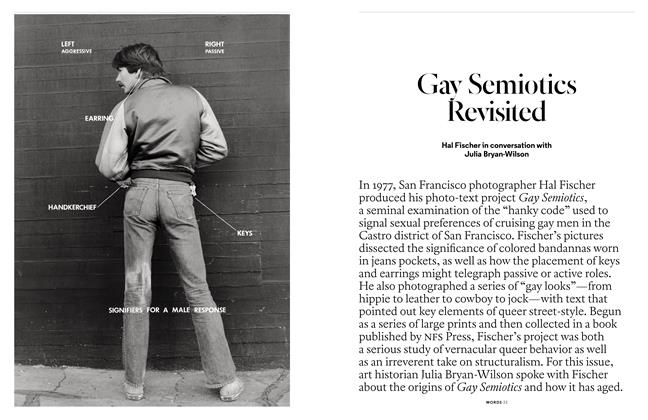

Words

WordsGay Semiotics Revisited

Spring 2015 By Julia Bryan-Wilson -

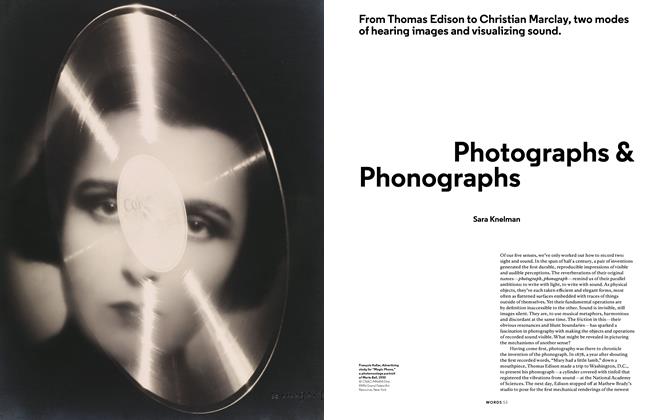

Words

WordsPhotographs & Phonographs

Fall 2016 By Sara Knelman