Collier Schorr Humanity, Visibility, Power

A Conversation with Matthew Higgs

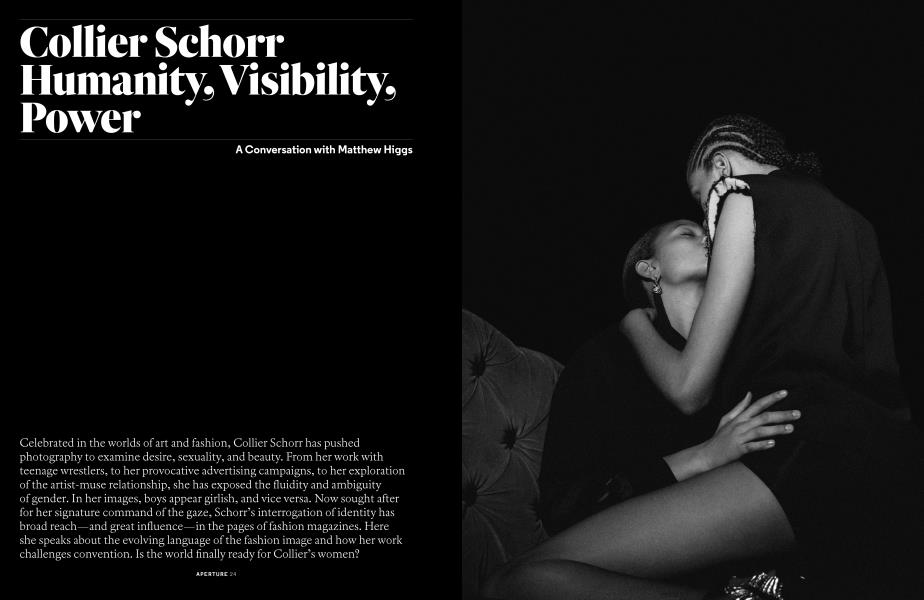

Celebrated in the worlds of art and fashion, Collier Schorr has pushed photography to examine desire, sexuality, and beauty. From her work with teenage wrestlers, to her provocative advertising campaigns, to her exploration of the artist-muse relationship, she has exposed the fluidity and ambiguity of gender. In her images, boys appear girlish, and vice versa. Now sought after for her signature command of the gaze, Schorr’s interrogation of identity has broad reach—and great influence—in the pages of fashion magazines. Here she speaks about the evolving language of the fashion image and how her work challenges convention. Is the world finally ready for Collier’s women?

Matthew Higgs: I am going to start with a quote you put on your Instagram feed. It says: “For anyone who wonders why I wanted to make fashion pictures, now you know.” And there is the hashtag #humanityvisibilityequalspower. What animated that? I think it’s worth mentioning that this conversation is taking place two days after Trump’s executive order on immigration.

Collier Schorr: For me, Instagram is a dual platform for showing your work and for showing what you stand for. The picture I made for Saint Laurent, which accompanied the post, was more typical of a documentary picture than a fashion advertisement. Any one element could be seen as typical, but the models were styled and encouraged to perform and play outside of what is traditionally seen: heteronormal women.

We all know that fashion is theater. But it felt like a real moment when I was with those models, Selena Forrest and Hiandra Martinez. Because I was working alongside filmmaker Nathalie Canguilhem, who was also directing them, I could watch as though I were a voyeur. Or, more correctly, there was a performance that seemed to be happening outside of my command. I wasn’t prepared for what it would feel like to see that image as a billboard. It took me back to when I first started making art. I wanted to essentially make a billboard in a gallery that talked about visibility and representation at a time when there was no real lesbian representation in the art world.

M H: Your imagery circulates in the context of both the art world and the larger world of fashion. How would you characterize the differences between these cultural, social, and, I guess, political spheres?

CS: They are both places where you have an audience. I don’t really distinguish between the two audiences, because for the most part, they are the same people. More people look at advertising than go to galleries. But everybody who goes to a gallery looks at advertising.

MH: Do you think there’s a resistance, still, from the art context to artists who choose to work in the realm of fashion?

CS: I’ve always dealt with resistance, though not based on commercial work, but on making too many pictures of men and being seen as romantic. Or based on being an American artist working in Germany. Or not showing in Germany because the work was too American or because it was too dangerous. I’ve never had “permission” or been associated with a collective or a movement. The politics of the work left people uncertain of my identity. Was I a gay male? If I had been a gay male, I think there would have been more support for the work, because there is a tradition of gay men making work about male beauty.

M H: But that’s sort of the uncertain nature of the work in its totality. It remains disruptive to the stability the art world has sought.

CS: The last gallery show I did, 8 Women (2014), which was seventy percent archival commissioned work and thirty percent work that I made before I started doing fashion, was the most successful show I’ve had. It sold the most. It sold to museums. I walked away thinking, Oh, of course it did well. They’re pictures of women, and that’s always been a comfortable spot for art. I did feel like I was being radical by bringing in commercial work, but I was being really traditional by bringing in female nudes.

M H: It seems almost every decade there’s an attempt to align or embrace the fashion image in the art world. There are exhibitions that address this, and everyone feels like it’s been done, and then a decade later it’s addressed again. Whereas now it seems it’s at its most interesting, most widespread, and hopefully—or potentially—most complex.

I’ve never had "permission” or been associated with a collective or a movement. The politics of the work left people uncertain of my identity.

WORDS

As boys have become more objectified, we are left with an ambiguous fashion body that is both male and female.

CS: In terms of destabilizing, my situation might be the result of not having an identity as an artist, a photographer, painter, et cetera. I became an artist really—I wouldn’t say “by accident,” but I didn’t study art. I didn’t train. I just had friends who were artists, and I worked in a gallery. I thought I was a writer. And I made work simply because I thought that the photoand text-appropriation world made it possible for somebody to make something without having any talent.

I was working for Peter Halley and Richard Prince, and I had the opportunity to curate a show at 303 Gallery of friends of mine. I put myself in the show because there was a hole, a kind of representation, or protest, that wasn’t yet included.

So I appropriated fashion imagery. It was a way of interacting with those images that I was drawn to from magazines. What I’m doing today is still the same thing. I never believed in a high-art position because I never fantasized about being an artist.

MH: But a distinction would be that you’re producing those images now, as opposed to working with those images.

CS: Well, yes and no. My current Saint Laurent men’s campaign is collage. The images were shot as an advertising campaign, but by printing them out and cutting them up, they became commentary, a secondary text breaking down an original, static conceit. It’s an infiltration of representation, by bringing together a bunch of pictures made under one umbrella to create a dialogue on representation. The clothing is cut up, cut out; the characters become more important and have more authority. As though I were taking some Guess ads out of Vogue from 1989 and coilaging them for an artwork. That was the proposition of my show 8 Women— images go out into the world in magazines, and then I take back those that I want to have a second comment on. I restage their being looked at.

MH: The commercial imperative of the fashion business dictates that it’s constantly in flux. Then there’s the marketdriven flux, and the commercial realities of fashion. Is it possible to think about that when you’re trying to create an image within those structures?

CS: I think almost everything that’s bad about working in fashion is also good, depending upon the day. The fact that it moves. The fact that it’s disposable. The fact that you are so invested in something that you’re willing to have a huge fight over it. Then it gets thrown in the garbage. No matter how bad or no matter how good a picture is, it evaporates after six months. It’s not enshrined. I guess I keep what I love, by putting it into a frame.

MH: In the work you’ve done with Saint Laurent, do you have increasing license to make—this is a crude way to put it— more complicated images?

CS: I have the encouragement to do that, and that’s very rare. The designer at Saint Laurent, Anthony Vaccarello, was very interested and invested in seeing pictures come from the artist’s imagination rather than from the position of merchandising.

MH: To return to #humanityvisibilityequalspower, that Instagram hashtag, what do you think about recent shifts in fashion casting and the bodies we’re seeing in this context?

CS: There is a real push toward diversity, but I think the fashion world has treated diversity in casting as a smoke bomb, because there is very little diversity in production. There are very few black fashion photographers in mainstream magazines. There are not that many black designers. But the casting revolution has been great because it’s releasing people who were stuck having to be represented by a certain ideal of beauty. I’m still very much concerned with the general ways I/we present women and sell an idea about them. How to shift what objectification does, how it functions. I’m suspect of merely propping up a picture by suggesting the woman has power.

M H: How do you approach the space of editorial work? To me, it’s substantially different from your approach to making a book, or making an exhibition, or even working with a client like Saint Laurent. The continuous narrative of editorial opens up a different agenda.

CS: For me, the best-case scenario of editorial work is being in a kind of consensual relationship with somebody else in which I can explore who they are, what they look like, and why they’re desirable.

M H: And the other person is the model?

CS: The other person is the model. Sometimes it’s a fleeting relationship, and sometimes it’s a sustained relationship. I’m really interested in a certain kind of seduction or flirtation. Like, you’re at a club, and you find your person, and you make this conversation, and then you get to do everything you want with them in this very consensual way. We fall in love with someone who is in love with themselves, and then we fall in love with our version of them. They can love you for a minute for recognizing them. Then some kid rips it out of a magazine, puts it on their bedroom wall, and has someone to dream about.

MH: The early weeks of the Trump administration left many people—and commentators, in the broader sense, including artists—stunned. How do you see fashion in relation to the current political reality?

CS: I’ve always had a really simple idea about what I wanted for my fashion pictures, because I think that they can only do so much based on the fact that it’s all fake, for the most part. Is it intimacy? Is intimacy a kind of gaze of empowerment, inclusion, and warmth?

Fashion basically promised me one day I would have a girlfriend, and she might be like that model in a sailor shirt with short bleached hair. She might not. But I could fantasize about it. And, at the same time, I could be repulsed by fashion images. I could be hurt by fashion images. And, I could be scarred by fashion images.

I wanted to replace the pictures I found alienating with my pictures, so that I would somehow create a healthier pictorial environment for kids. I think you see trends in personal relationships and sexuality more than politics, probably.

M H: There was a great essay in the early ’8os by Rosetta Brooks where she was writing about Guy Bourdin and Helmut Newton, and specifically about Bourdin’s lingerie catalog for Bloomingdale’s, and there was a critical pushback against certain kinds of commercial imagery that were counter, in that case, to a feminist narrative.

CS: I have a lot to say about that essay, which, of course, I read when it came out. I think that’s the genesis of my dilemma and ultimately my position. As an art maker in the late ’80s, I was raised on French postfeminism and Laura Mulvey, and Silvia Kolbowski and Barbara Kruger, and all these ideas that essentially told me that representation of women was forbidden, that representations of women in the media had caused so much damage. That’s why I started making pictures of boys, and didn’t make a photograph of a girl until 1995 or something.

MH: These later works include projects like JfensF. (2005), your photographs of wrestlers (1999-2004), and Americans (2012)?

CS: Yes. I had been working on a project exploring gender in poses by posing a boy as Andrew Wyeth’s model Helga Testorf. The book Jens F. traces all these painters’ ideas about a woman’s body. By making a boy pose as a woman, I thought it might make him more vulnerable. It didn’t. Boys are boys, and they don’t suddenly emote tons if they hold their hands behind them and arch their backs. Toward the end of that project, which took six years, I met a woman who looked exactly like Wyeth’s muse, and I shot her naked in some of those same poses. I finally felt that working with the boy for all those years was repressive and exclusionary and that there wasn’t a solution to representation. There never will be.

That was a huge moment for me, because I felt really guilty about it, and then really free. My issue with everything I learned is that it was funneled through heterosexual feminism. They had no use for the beautiful fashion woman—that was an image that made their relationships with men difficult. Well, if you’re not having a relationship with a man, and in fact you desire women, you have a very different reaction to that image. My work is a continuation of what those women were interested in, but it doesn’t take patriarchy into consideration in the same way. My problem with some of that stuff was that it erased desire for the female gaze.

I wouldn’t have had an early gay identity if it wasn’t for fashion. Those images worked really differently on me, because I didn’t have to live up to that girl. I just could hope to meet her. I could look in a mirror and know that I was not going to be her. And, if I chose, I could take on that Helmut Newton woman. I could reengage with those ideas.

When I first started, clients would say, "Do you think she’s going to make the model look like a lesbian?” Now they say, "We want Collier’s woman.”

M H: I’ve noticed a reemergence of nudity in fashion editorials. It’s just absolutely widespread.

CS: It’s a tits bonanza. I was talking about it with the model Freja Beha, whom I have shot topless many times. We both agree that for us, it’s not about showing breasts, but about being free of breasts enough to take your shirt offlike a boy. It’s a rejection of having to hide. My first pictures, the ones of the boy in lipstick, were all about the desire to be shirtless.

M H: I was curious about this reappearance of the naked body, aligned with the fact that different kinds of people now participate in the construction of these images and different people are the subject of these images. And it’s clearly not Helmut Newton nudity, or Guy Bourdin nudity.

CS: But sometimes it’s based on those nudities. It would be interesting for me to go through every nude picture I’ve done, or seminude picture, and point to when I think it’s an interesting, ambiguous, fuck-you, sexy, lesbian-gaze picture, or when it’s making a picture for somebody else. I do think as boys have become more objectified and sexualized over the years, we are left with a somewhat ambiguous fashion body that is both male and female.

M H: Nudity takes many forms, like when Juergen Teller starts to appear naked in his own images.

CS: I was just reading about Juergen, and he said that he knew he looked like shit and he didn’t care. He had gained weight. Maybe, on some level, he felt he should be subjected to the same harsh light as his subjects. Men and women are really different. It’s difficult to find a woman who would feel okay about feeling like they look like shit, and getting kind of a last laugh by making the picture.

I think about Francesca Woodman and Ana Mendieta, even Carolee Schneemann; these women looked good. I think it’s also a way of branding that male artists have often done, to great success, in ways that female artists, besides Cindy Sherman, have not been able to do. The male body is afforded a lot more flexibility. It is more acceptable in all shapes and sizes.

MH: It seems so repetitive now. If it had a purpose or a function, or if it were seeking to establish a kind of tension, that would all be gone. But then, I think male nudity feels disruptive within fashion publishing.

CS: Seeing a naked man feels more disruptive, for sure. It feels more interesting. I’ve taken more male nudes than female nudes in the last couple of years. But like anything, familiarity breeds discontent.

M H: With the boy with the lipstick and the desire to be shirtless, is that something that’s just there? Or is it something that’s quite self-conscious in the work you’re doing in fashion, and its relationship to the self, self-portraiture, self-identity, projection of the self?

CS: When I’m photographing somebody, I start to think I look like them. I start to talk like them. I’m looking at them so much through the camera, and having these kinds of reverberations from adolescence, when I looked at pictures and wanted to look like that. I’d want to wear those clothes. In the beginning, my first pictures were like, I wish I were a boy and that’s the boy I would be. Then it became, I wish that I were in World War II and I captured a Nazi, and this is how I would treat him.

MH: Do you ever suppress that subjectivity in the work?

CS: Sometimes it’s less about me and more about the person. I work with a model named Casil McArthur, who just got trans surgery. I met Casil at sixteen, when he was biologically a girl identifying as a boy. Now he’s eighteen, and he doesn’t have the breasts. As much as I saw myself in him, it wasn’t me. I was never a boy really; I just liked things boys had. Because he is a fashion model, and has been one since he was thirteen, I shot him for fashion magazines, but I don’t see them as exclusively any one thing. Self-portraits using a surrogate? A continuation of that first shirtless boy? Editorializing? Documentary?

M H: A more objective way.

CS: Yes. It had less to do with me, because it wasn’t even something that I had wanted for myself. It was just feeling like I was suddenly in the presence of something that was very different from my own identity, but connected to viability and visibility.

M H: I always like looking at Bruce Weber’s pictures because you can see what he’s enjoying. It doesn’t have to be a naked guy. It could be a dog. There’s a real pleasure for the viewer that’s mutual, even if you’re not fixated on what he’s fixated on. But it seems to me very honest photography.

CS: Well, that’s what’s being sold to you, isn’t it? When I left Art + Commerce and didn’t have an agency, Shea Spencer, my current agent, looked at my work and said, “Ask yourself:

Why is Bruce Weber so successful?” I said, “I don’t really know.” Shea said, “Because everybody wants to be in that picture. They want to be in that place. It’s sunny. People are smiling. People are clean. It’s easygoing.” And then he said, “Only a handful of intellectuals want to be in your world. Only some leather queens want to be in your world, and those people are not going to support you. Just because they love you, they’re still not going to be able to support you.”

When I first started, clients would say, “Well, we really love her work, but do you think she’s going to make the model look like a lesbian?” Now they come and they say, “We want Collier’s woman.” I’m not the only one doing Collier Schorr women now. Men who used to photograph women with their legs spread up in the air are also doing Collier Schorr women. There is a saying: “Make one picture for ‘them’ and another for yourself.” Slowly try to make them want the pictures that you want.

Matthew Higgs is Director and Chief Curator of White Columns, New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

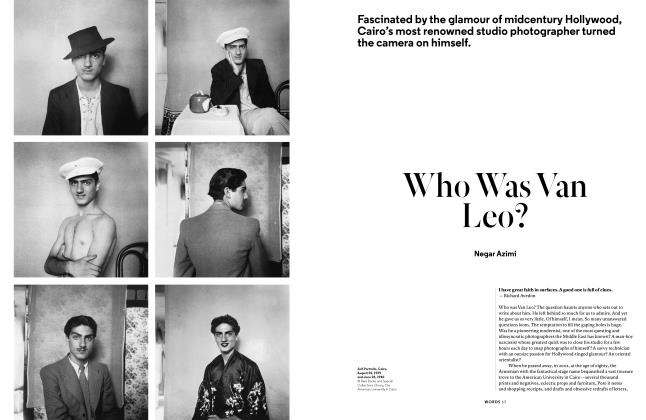

WordsWho Was Van Leo?

Fall 2017 By Negar Azimi -

Words

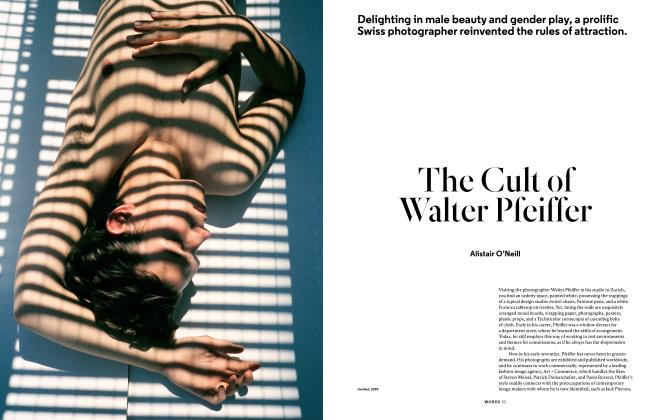

WordsThe Cult Of Walter Pfeiffer

Fall 2017 By Alistair O’Neill -

Pictures

PicturesPieter Hugo Beijing Youth

Fall 2017 By Stephanie H. Tung -

Pictures

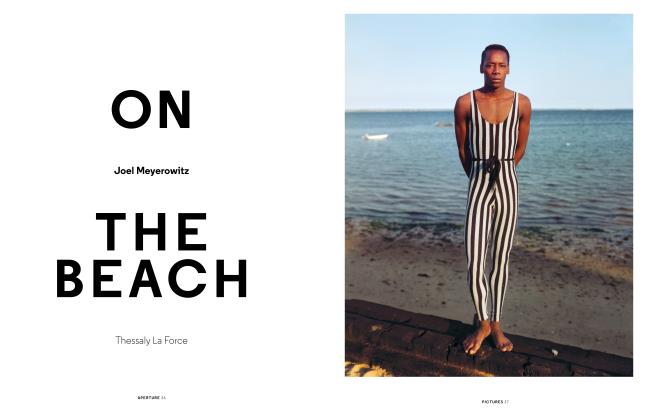

PicturesJoel Meyerowitz: On The Beach

Fall 2017 By Thessaly La Force -

Words

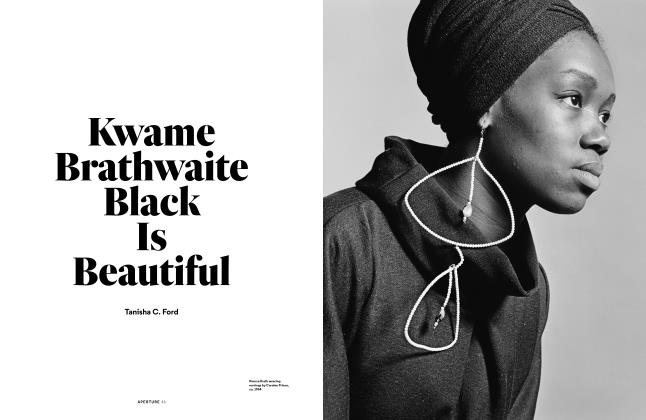

WordsKwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful

Fall 2017 By Tanisha C. Ford -

Pictures

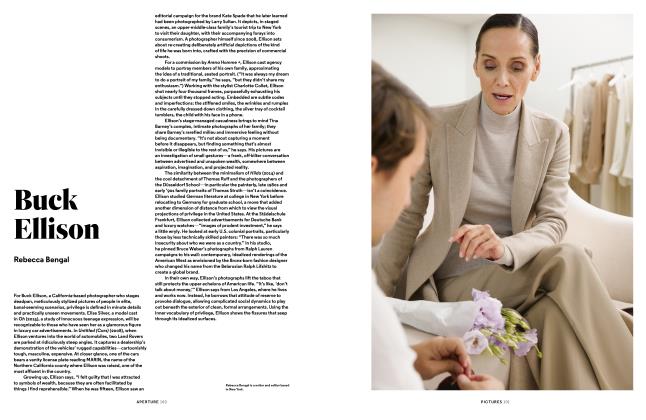

PicturesBuck Ellison

Fall 2017 By Rebecca Bengal

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Words

-

Words

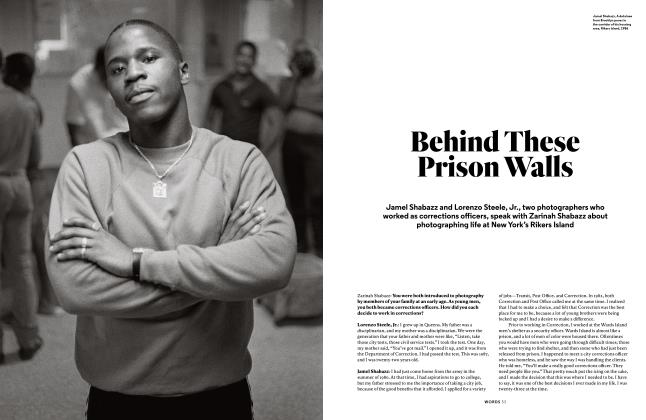

WordsBehind These Prison Walls

Spring 2018 -

Words

WordsAnnabelle Selldorf

Spring 2020 -

Words

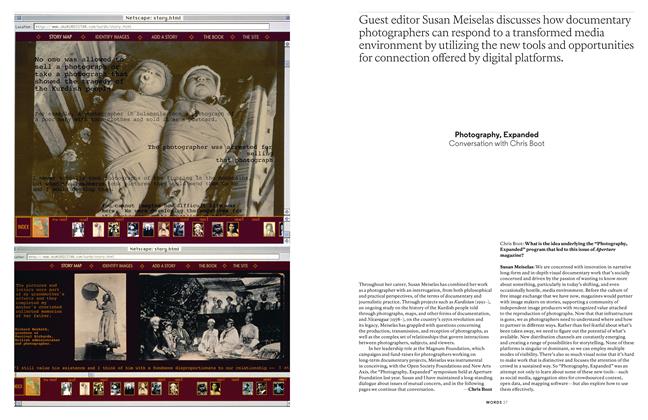

WordsPhotography, Expanded

Spring 2014 By Chris Boot -

Essay

EssayFrom Ecstasy To Agony: The Fashion Shoot In Cinema

Spring 2008 By David Campany -

Words

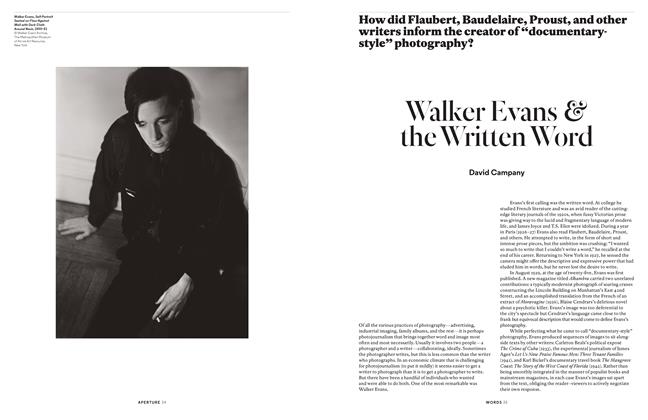

WordsWalker Evans & The Written Word

Winter 2014 By David Campany -

Words

WordsSurface Tension

Summer 2020 By Lou Stoppard