Lyle Ashton Harris

Vince Aletti

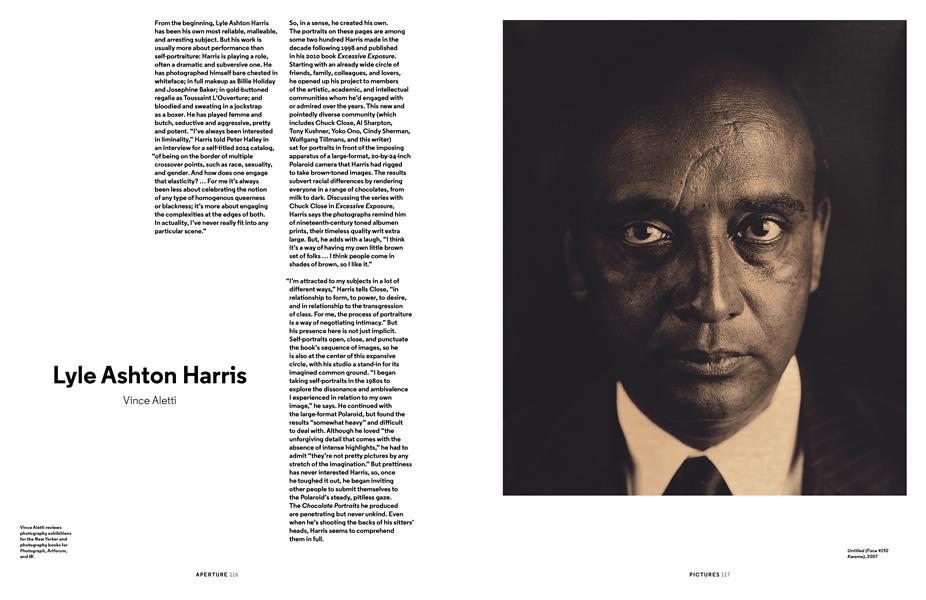

From the beginning, Lyle Ashton Harris has been his own most reliable, malleable, and arresting subject. But his work is usually more about performance than self-portraiture: Harris is playing a role, often a dramatic and subversive one. He has photographed himself bare chested in whiteface; in full makeup as Billie Holiday and Josephine Baker; in gold-buttoned regalia as Toussaint L’Ouverture; and bloodied and sweating in a jockstrap as a boxer. He has played femme and butch, seductive and aggressive, pretty and potent. "I’ve always been interested in liminality,” Harris told Peter Halley in an interview for a self-titled 2014 catalog, "of being on the border of multiple crossover points, such as race, sexuality, and gender. And how does one engage that elasticity? ... For me it’s always been less about celebrating the notion of any type of homogenous queerness or blackness; it’s more about engaging the complexities at the edges of both.

In actuality, I’ve never really fit into any particular scene.”

So, in a sense, he created his own.

The portraits on these pages are among some two hundred Harris made in the decade following 1998 and published in his 2010 book Excessive Exposure. Starting with an already wide circle of friends, family, colleagues, and lovers, he opened up his project to members of the artistic, academic, and intellectual communities whom he’d engaged with or admired over the years. This new and pointedly diverse community (which includes Chuck Close, AI Sharpton,

Tony Kushner, Yoko Ono, Cindy Sherman, Wolfgang Tillmans, and this writer) sat for portraits in front of the imposing apparatus of a large-format, 20-by-24-inch Polaroid camera that Harris had rigged to take brown-toned images. The results subvert racial differences by rendering everyone in a range of chocolates, from milk to dark. Discussing the series with Chuck Close in Excessive Exposure,

Harris says the photographs remind him of nineteenth-century toned albumen prints, their timeless quality writ extra large. But, he adds with a laugh, "I think it’s a way of having my own little brown set of folks... I think people come in shades of brown, so I like it.”

"I’m attracted to my subjects in a lot of different ways,” Harris tells Close, "in relationship to form, to power, to desire, and in relationship to the transgression of class. For me, the process of portraiture is a way of negotiating intimacy.” But his presence here is not just implicit. Self-portraits open, close, and punctuate the book’s sequence of images, so he is also at the center of this expansive circle, with his studio a stand-in for its imagined common ground. "I began taking self-portraits in the 1980s to explore the dissonance and ambivalence I experienced in relation to my own image,” he says. He continued with the large-format Polaroid, but found the results "somewhat heavy” and difficult to deal with. Although he loved "the unforgiving detail that comes with the absence of intense highlights,” he had to admit "they’re not pretty pictures by any stretch of the imagination.” But prettiness has never interested Harris, so, once he toughed it out, he began inviting other people to submit themselves to the Polaroid’s steady, pitiless gaze.

The Chocolate Portraits he produced are penetrating but never unkind. Even when he’s shooting the backs of his sitters’ heads, Harris seems to comprehend them in full.

Vince Aletti reviews photography exhibitions for the New Yorker and photography books for Photograph, Artforum, and W.

PICTURES

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Pictures

PicturesJamel Shabazz

Summer 2016 By Khalil Gibran Muhammad -

Pictures

PicturesLatoya Ruby Frazier

Summer 2016 By Teju Cole -

Words

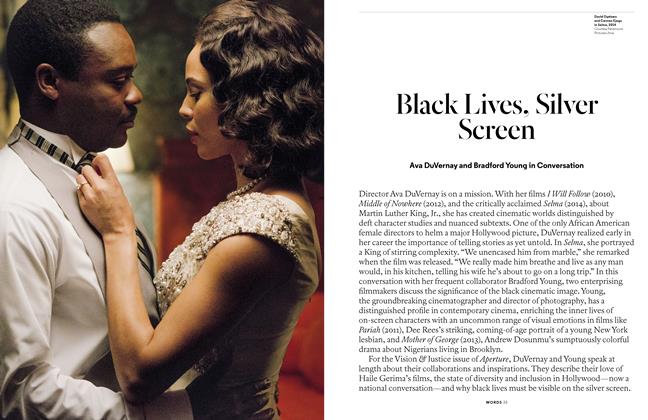

WordsBlack Lives, Silver Screen

Summer 2016 -

Pictures

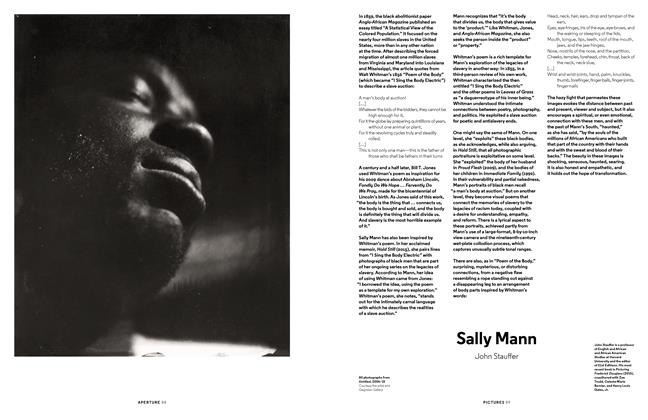

PicturesSally Mann

Summer 2016 By John Stauffer -

Pictures

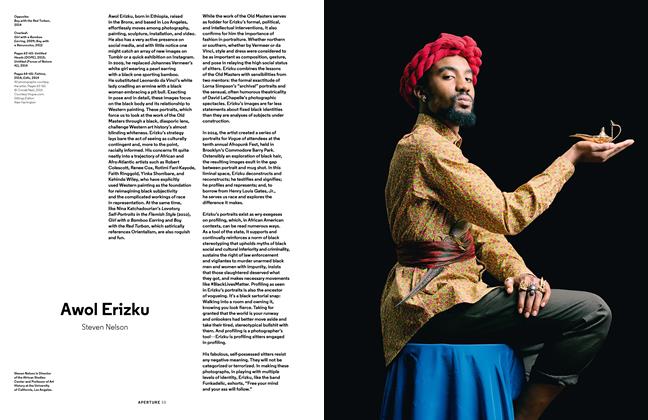

PicturesAwol Erizku

Summer 2016 By Steven Nelson -

Pictures

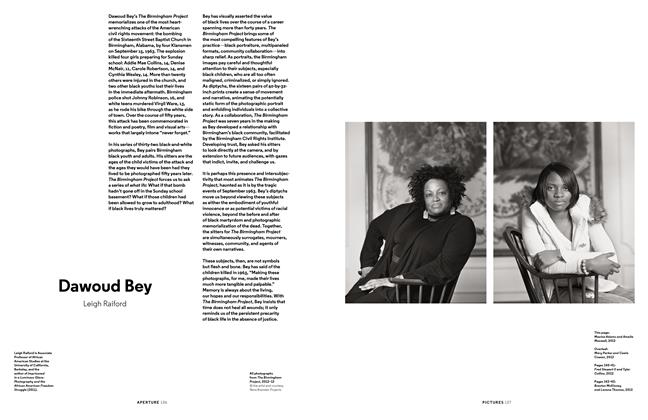

PicturesDawoud Bey

Summer 2016 By Leigh Raiford

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Vince Aletti

-

Vince Aletti

Fall 1994 By Vince Aletti -

♀ Madonna With ♂ Vince Aletti

Summer 1999 By Vince Aletti -

Portfolio

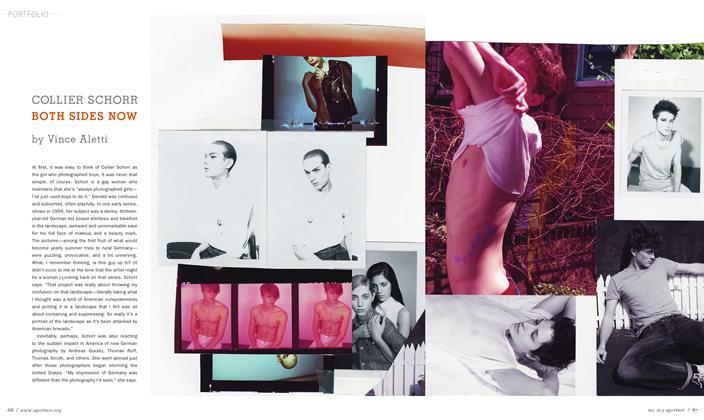

PortfolioCollier Schorr Both Sides Now

Spring 2011 By Vince Aletti -

Redux

ReduxIn Our Terribleness

Winter 2013 By Vince Aletti -

WORDS

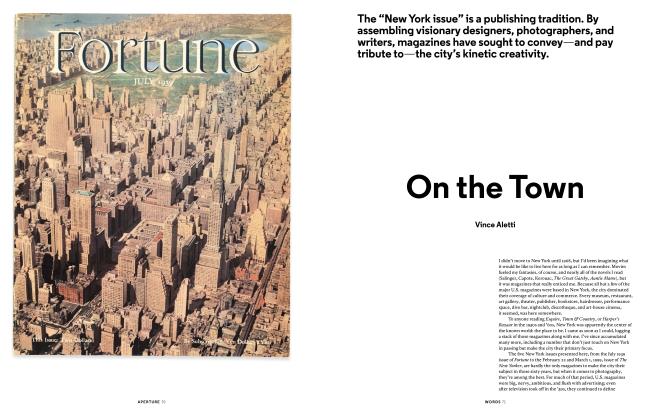

WORDSOn the Town

Spring 2021 By Vince Aletti -

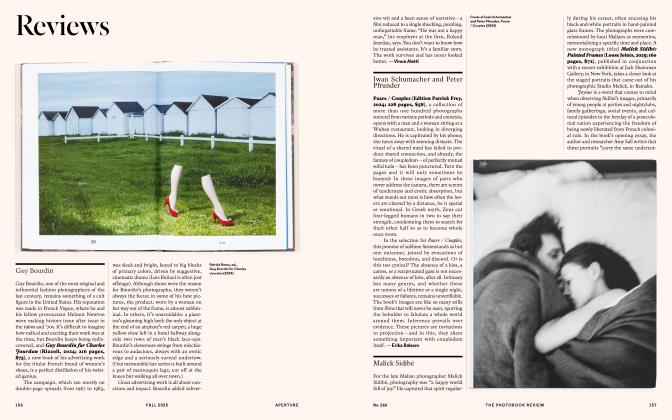

Reviews

FALL 2025 By Vince Aletti, Erika Balsom, Dalya Benor, 2 more ...

Pictures

-

Pictures

PicturesPictures

Summer 2013 -

Pictures

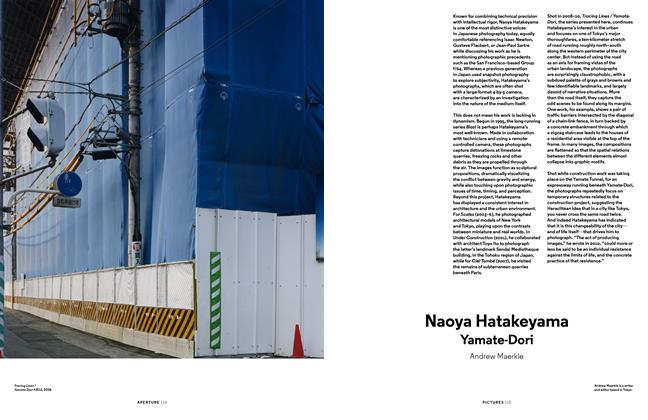

PicturesNaoya Hatakeyama

Summer 2015 By Andrew Maerkle -

Pictures

PicturesMickalene Thomas: Orlando Now

Summer 2019 By Antwaun Sargent -

Pictures

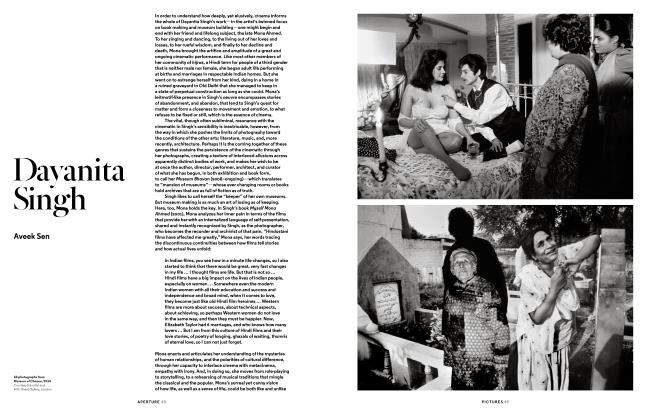

PicturesDayanita Singh

Summer 2018 By Aveek Sen -

Pictures

PicturesPaul Trevor

Winter 2013 By Chris Boot -

Pictures

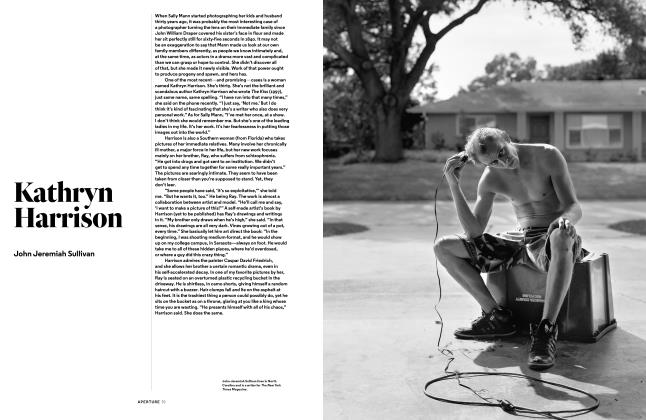

PicturesKathryn Harrison

Winter 2018 By John Jeremiah Sullivan