SILVER, SALT AND SUNLIGHT

REVIEWS

William Henry Fox Talbot was famously compelled toward the salted-paper photographic process while on his honeymoon at Lake Como, in 1833, when he found himself unable to render to his satisfaction a drawing of the lake, even with the help of a camera lucida. Early the following year, he began exploring with paper sensitized with table salt and silver nitrate, then exposed in daylight, and his experiments eventually proved successful. Talbot initially described the results as “photogenic drawing,” and later came to name the process the calotype (from the Greek for “beautiful impression"). He stated: “I do not profess to have perfected an art but to have commenced one, the limits of which it is not possible at present exactly to ascertain. I only claim to have based this art on a secure foundation.”

Talbot, an English aristocrat, had financial means, a knowledge of prior experiments with light sensitivity, and an overwhelming desire for a fixed image. Curiously, these same factors were simultaneously united in France in the figure of Louis-JacquesMandé Daguerre. Daguerre’s and Talbot’s respective photographic imaging techniques were both made public in January 1839.

With a focus on images from the “golden age” of early paper photography, the 1840s to the 1870s, curator Anne Havinga has organized an exquisite exhibition, Silver, Salt and Sunlight: Early Photography in Britain and France at the Museum of Fine Arts. A variety of well-known photographers are represented, including Talbot, Anna Atkins, Félix Nadar, Julia Margaret Cameron, and Roger Fenton. (Due to their continued sensitivity to light, several of the displayed photographs are rotated over the course of the exhibition.) They and other photographic artists, studio photographers, and wealthy amateurs represent a range of technical possibility with regard to the salt print, as well as a gamut of contexts and aesthetic inclinations.

Charles Marville’s evocative and understated Au Siège de Sébastopol (1865-66) is one in a series of more than four hundred photographs, begun in 1862, documenting the splendor of a modernizing Paris under Baron Haussmann, decades before Eugène Atget would attempt to preserve “old Paris.” Francis Frith’s Pyramids of Sakkarh (1858), a technical marvel made on location in Egypt, speaks to the demand for travel imagery during the expansion of the Second British Empire in the Victorian Era. These military activities are also alluded to in Joseph Cundall’s Two Military Musicians (1856), a studio portrait commissioned by Queen Victoria, of returning soldiers from the Crimean War— incidentally, the first war ever recorded by a camera.

Working by the seashore, but finding it impossible to record both the sea and the sky in a single negative, Gustave Le Gray found an elegant solution. In Cloudy Sky—The Mediterranean with Mount Agde (1857), he composited separate negatives into one print, displaying the environment not as it was, but as he saw it. Both his technical innovation and his exertion of aesthetic will seem to predict future forms of photography.

With subjects from the banal to the spectacular, this exhibition offers insights into the sensibilities and activities of a midnineteenth-century population, living in the midst of massive technological and social changes as the Industrial Revolution drew to a close.©

Ben Sloat

Silver, Salt and Sunlight: Early Photography in Britain and France was presented at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, February 7-August 5, 2012.

Ben Sloat is an artist and educator; he teaches in the MFA in Photography program and the MFA in Visual Arts program at the Art Institute of Boston at Lesley University.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

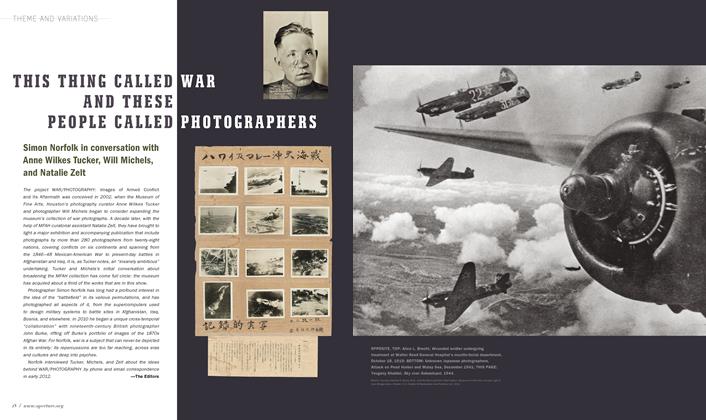

Theme And Variations

Theme And VariationsThis Thing Called War And These People Called Photographers

Fall 2012 By Simon Norfolk, The Editors -

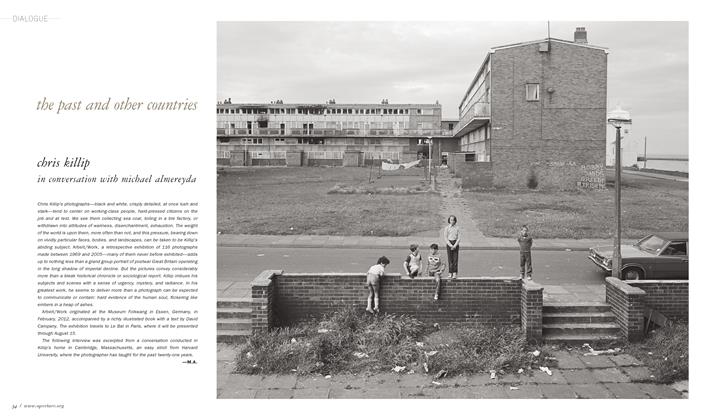

Dialogue

DialogueThe Past And Other Countries

Fall 2012 By Michael Almereyda -

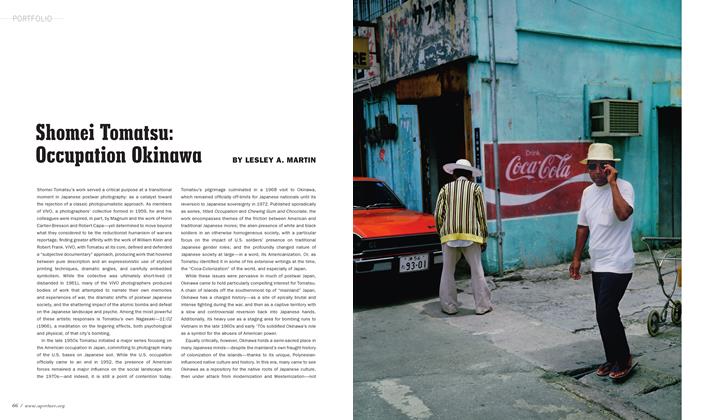

Portfolio

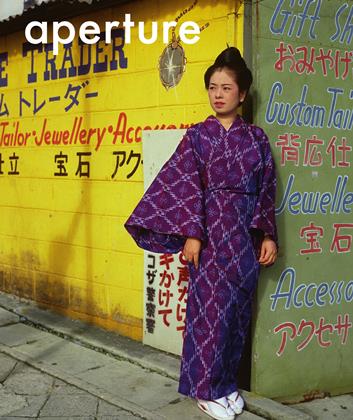

PortfolioShomei Tomatsu

Fall 2012 By Lesley A. Martin -

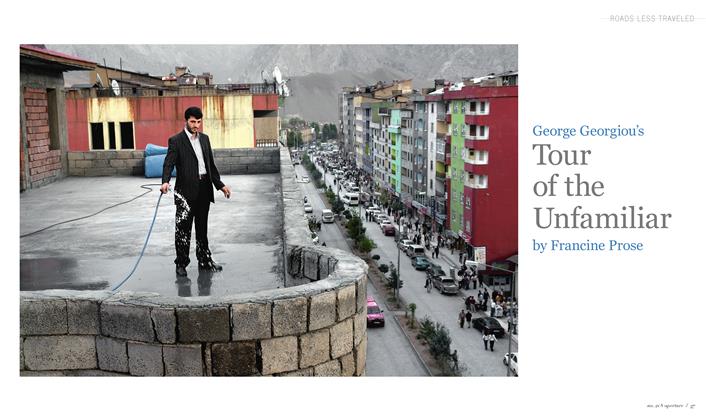

Roads Less Traveled

Roads Less TraveledGeorge Georgiou’s Tour Of The Unfamiliar

Fall 2012 By Francine Prose -

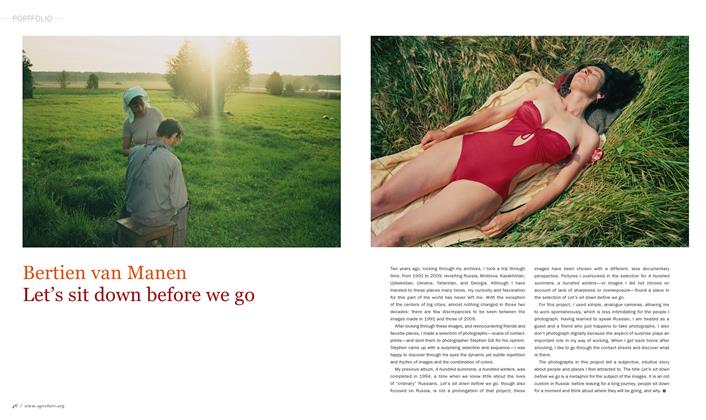

Portfolio

PortfolioBertien Van Manen Let's Sit Down Before We Go

Fall 2012 By Bertien Van Manen -

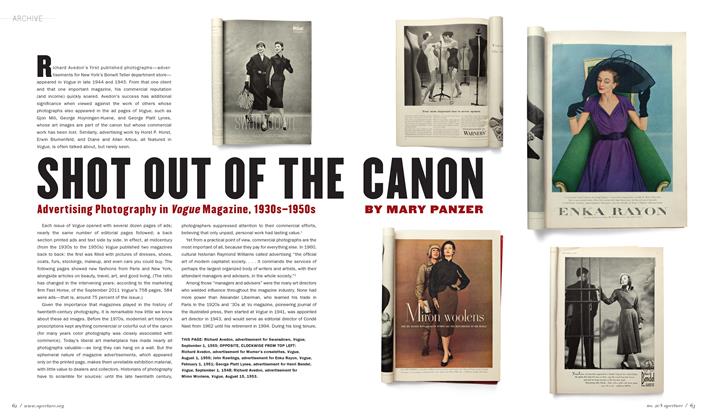

Archive

ArchiveShot Out Of The Canon

Fall 2012 By Mary Panzer

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Reviews

-

Reviews

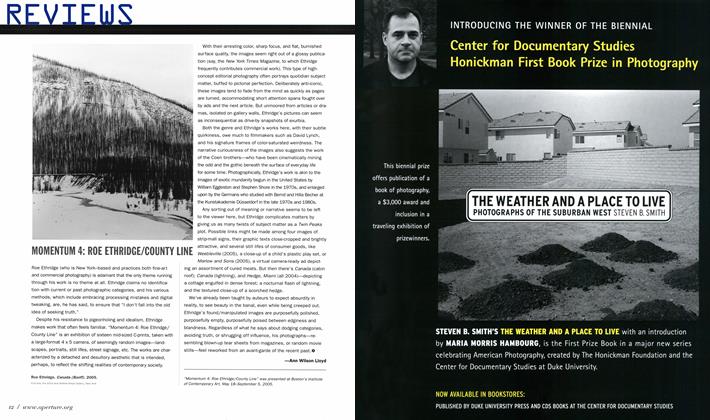

ReviewsMomentum 4: Roe Ethridge/county Line

Winter 2005 By Ann Wilson Lloyd -

Reviews

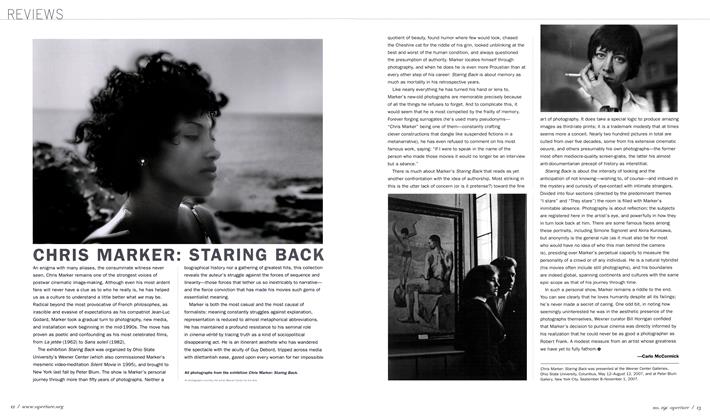

ReviewsChris Marker: Staring Back

Spring 2008 By Carlo McCormick -

Reviews

ReviewsRaymond Depardon Silence Rompu

Spring 2000 By Diana C. Stoll -

Reviews

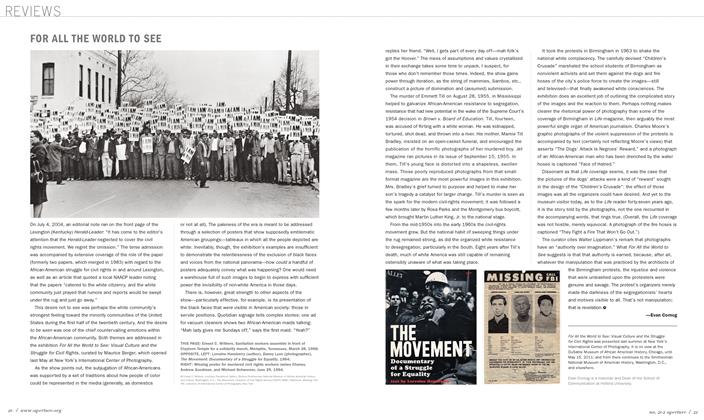

ReviewsFor All The World To See

Spring 2011 By Evan Cornog -

Reviews

ReviewsShomei Tomatsu: Skin Of The Nation

Spring 2005 By Lyle Rexer -

Reviews

ReviewsAbout Face

Winter 2004 By Vince Aletti