NOTE

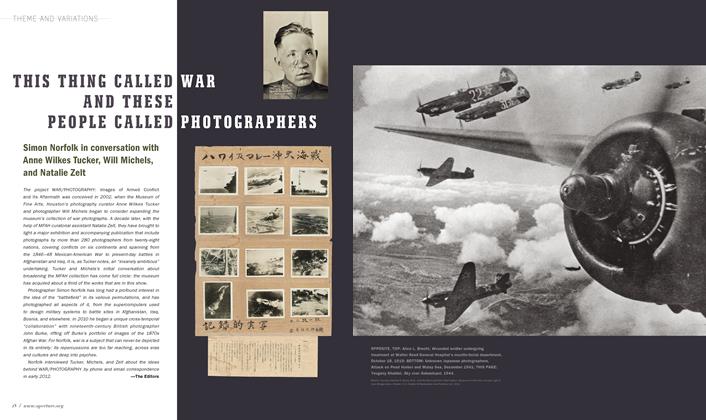

For more than a decade—and for the full stretch of the United States’ war in Afghanistan—curator Anne Wilkes Tucker has been planning a massive exhibition of war photography, scheduled to open this fall at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. We asked photographer Simon Norfolk, known for his reflective images of the aftermath of battles and his sharp thinking on documentary image making, to speak with Tucker, along with her colleagues Will Michels and Natalie Zelt, about the impetus for the show and the problems and questions they encountered along the way. Despite the inherent complications of war photography, and the limitations and evolutions of the medium—not to mention those posed by censorship—Tucker maintains that the still image is unique in its ability to satisfy “part of our brain that neither poetry nor film satisfies. It’s incomplete, yes. But it’s fixed.”

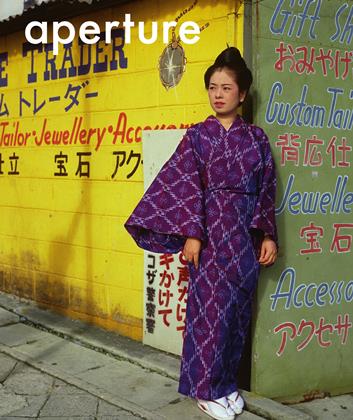

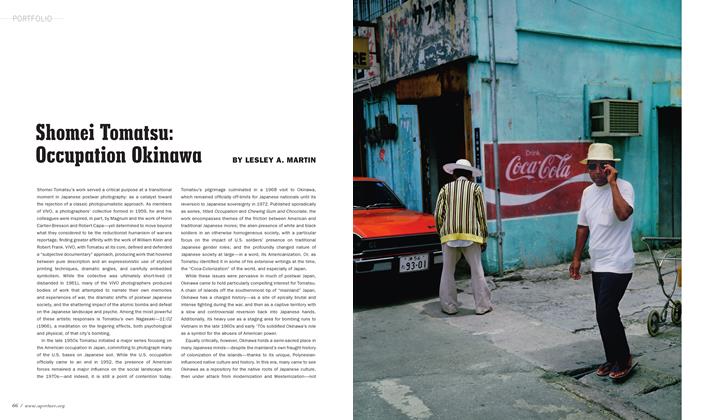

Japanese photographer Shomei Tomatsu is well known for his images chronicling a devastated Hiroshima leveled by the atomic explosion, as well as for his documentation of the island of Okinawa, longtime site of a U.S. military base and now the photographer’s home. Presented here is a portfolio of work from Okinawa, featuring a number of rarely seen color images that vividly reveal the contrasts between the local culture and the foreign presence on the island.

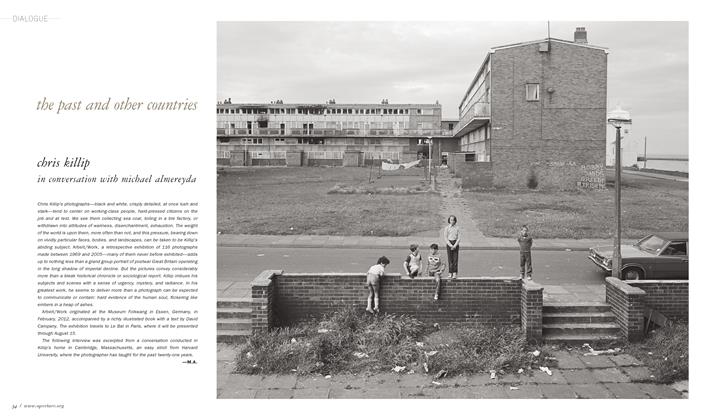

British documentary photographer Chris Killip, interviewed here by filmmaker Michael Almereyda, also brought his focus to chaotic postwar circumstances, turning his lens to the social decay—austere housing estates, the effects of high unemployment—of Britain during its postimperial decades. Killip, whose work is the subject of a retrospective exhibition that opened in Essen, Germany and is currently on view in Paris, reflects on the influence of Walker Evans, Paul Strand, and John Berger, observing that there is always a political dimension to photography.

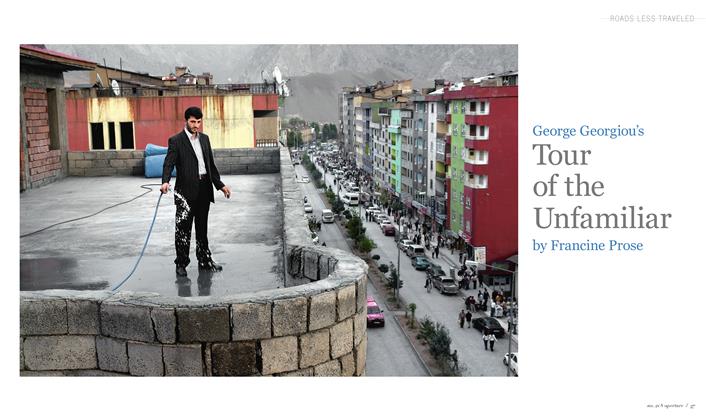

By contrast, the political and historical dimensions of George Georgiou’s photographs made in Turkey, Georgia, and Ukraine are more oblique: as writer Francine Prose points out, the images convey “an outsider’s experience of trying to puzzle things out.” With their seductive colors and enigmatic situations, Georgiou’s images avoid easy stereotypes of place, while reflecting on contrasts and bridges between East and West, tradition and modernity.

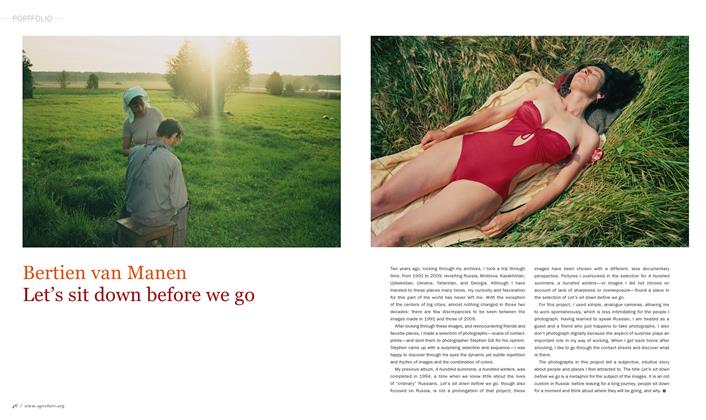

Bertien van Manen, too, uses color to startling effect in her loose, quiet, but evocative work made in Russia and neighboring countries over the course of twenty years. She captures day-to-day activities of rural life that, in her view, have changed very little despite the enormous transformations the country underwent in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Thomas Barrow’s work is likewise connected to place; in his case it is the developing American West of the 1970s, which provided visual “topographic" fodder for so many major American photographers. Barrow, however, curiously and obsessively scratches his negatives, a gesture that emphasizes the physicality of the image and questions its ability to function as a neutral window onto a location. Lucas Blalock, working four decades on, in a time when most photographs are tweaked with Photoshop to some degree, also points to the mechanisms of image making by awkwardly exposing the seams of a now-often-seamless digital process.

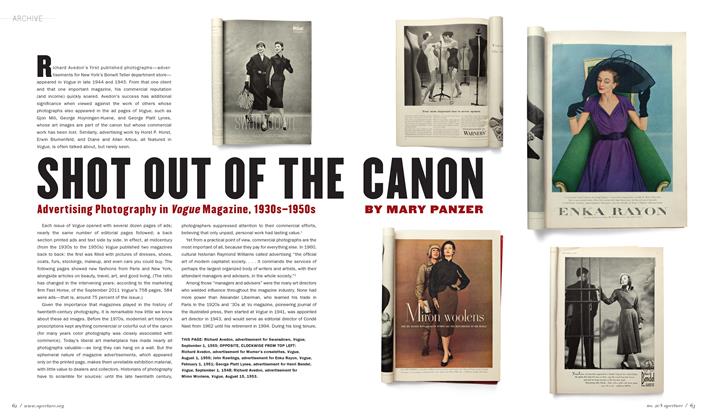

Mary Panzer looks at the underrecognized ad photography that appeared in Vogue magazine during the mid-twentieth century: images—often uncredited—by photographers who would soon become giants of the medium, including Richard Avedon and Diane Arbus.

In a continuation of her “Wanderings" series, Sylvia Plachy sets out on an unguided tour of self-portraits and self-examination—recalling the words of her compatriot, the late Hungarian ceramicist Eva Zeisel, whose philosophy of creating beauty was ostensibly so simple: “You just have to get out of the way."

The Editors

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Theme And Variations

Theme And VariationsThis Thing Called War And These People Called Photographers

Fall 2012 By Simon Norfolk, The Editors -

Dialogue

DialogueThe Past And Other Countries

Fall 2012 By Michael Almereyda -

Portfolio

PortfolioShomei Tomatsu

Fall 2012 By Lesley A. Martin -

Roads Less Traveled

Roads Less TraveledGeorge Georgiou’s Tour Of The Unfamiliar

Fall 2012 By Francine Prose -

Portfolio

PortfolioBertien Van Manen Let's Sit Down Before We Go

Fall 2012 By Bertien Van Manen -

Archive

ArchiveShot Out Of The Canon

Fall 2012 By Mary Panzer

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

The Editors

-

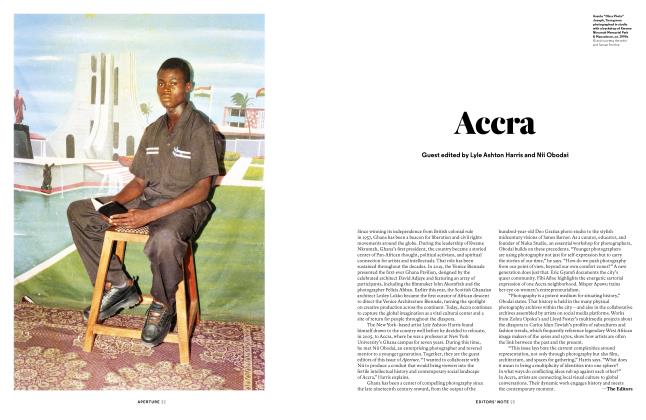

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteAccra

FALL 2023 By Lyle Ashton Harris, Nii Obodai, The Editors -

Pictures

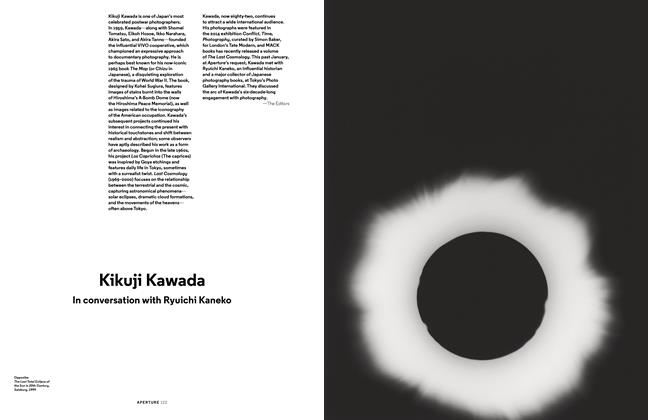

PicturesKikuji Kawada

Summer 2015 By Ryuichi Kaneko -

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteSelf And Shadow

Spring 1989 By The Editors -

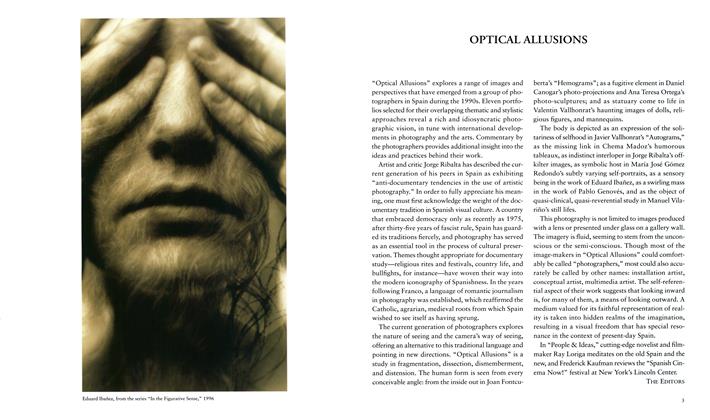

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteOptical Allusions

Spring 1999 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

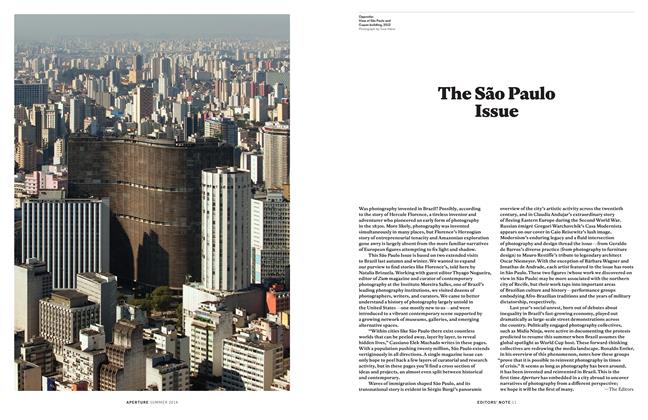

Editor's NoteThe São Paulo Issue

Summer 2014 By The Editors -

Object Lessons

Object LessonsThe Obi

Summer 2015 By The Editors