Theme And Variations

This Thing Called War And These People Called Photographers

Fall 2012 Simon Norfolk, The EditorsTHIS THING CALLED WAR AND THESE PEOPLE CALLED PHOTOGRAPHERS

THEME AND VARIATIONS

Simon Norfolk

Anne Wilkes Tucker

Will Michels

Natalie Zelt

The project WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath was conceived in 2002, when the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston's photography curator Anne Wilkes Tucker and photographer Will Michels began to consider expanding the museum’s collection of war photographs. A decade later, with the help of MFAH curatorial assistant Natalie Zelt, they have brought to light a major exhibition and accompanying publication that include photographs by more than 280 photographers from twenty-eight nations, covering conflicts on six continents and spanning from the 1846-48 Mexican-American War to present-day battles in Afghanistan and Iraq. It is, as Tucker notes, an “insanely ambitious” undertaking. Tucker and Miche Is’s initial conversation about broadening the MFAH collection has come full circle: the museum has acquired about a third of the works that are in this show.

Photographer Simon Norfolk has long had a profound interest in the idea of the “battlefield” in its various permutations, and has photographed all aspects of it, from the supercomputers used to design military systems to battle sites in Afghanistan, Iraq, Bosnia, and elsewhere. In 2010 he began a unique cross-temporal “collaboration” with nineteenth-century British photographer John Burke, riffing off Burke’s portfolio of images of the 1870s Afghan War. For Norfolk, war is a subject that can never be depicted in its entirety: its repercussions are too far reaching, across eras and cultures and deep into psyches.

Norfolk interviewed Tucker, Michels, and Zelt about the ideas behind WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY by phone and email correspondence in early 2012. —The Editors

SIMON NORFOLK: I want to kick off by asking a question I ask myself. When I’m starting on a project, the first thing I think is: “What will be the preconceptions of my audience before they see my work? What am I up against?" What notions did you start out with on WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY?

ANNE WILKES TUCKER: Several years ago, Will Michels, who had an interest in war and photography long before I did, asked me why the MFAH owned so few war photographs. I asked him to make a list of what he thought we should acquire. We began by looking at books—but we found that they were really lacking. First, there are the monographs that make giants out of Robert Capa or Don McCullin or Larry Burrows—and that’s all those books do. They lack context. Then there are the war-specific books: books about the photography of a particular conflict; these just address a single situation. So far, only certain Civil War photography books address both photographers’ intent and the military aspects of the photographs.

What we were trying to do with WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY was pull back and look across cultures, from war to war to war. What is the relationship between this thing called war and these people called photographers? We’re trying to understand the military, what they do and why they do it. And how photographs do or don’t reflect that. . . . It’s very complicated and insanely ambitious.

NATALIE ZELT: And because it’s so ambitious, and because we came at it with such a universalist purpose, we are constantly fighting against our own preconceived visions of what war looks like—just as all our viewers will be fighting against the Saving Private Ryan pictures in their heads, or what photographs of conflict they think should exist.

SN: My friends’ children see a fantastic amount of violence, but most of it is cartoon violence. They watch films where bullets get fired, but no one gets hurt and no one bleeds. That’s one preconception we all struggle with: people thinking that war is bloodless and fun. It has become a piece of entertainment in our culture.

NZ: Also, people tend to have an idea that war is “gentlemanly” in some bizarre way. . . .

AWT: But that’s how it’s been shown to them. In our book, on the one hand, we have pictures that represent war as it was shown to the public, as they consumed it either through newspapers or in Life magazine or whatever; then we have other pictures that show that same war from a totally different reality.

WILL MICHELS: For instance, there are two great pictures taken in Afghanistan, one by Luc Delahaye of a dead Taliban soldier, and another one of the same dead soldier by Seamus Murphy.

SN: But those are two photographers who are basically on the same side photographing the same thing. Is there any case where you’ve included, say, an American photographing an event, and a North Vietnamese photographing the same event?

AWT: There are a few cases. There’s a Wayne Miller photograph, taken during World War II on the USS Lexington, of pilots waiting to be called up, and another, by an unknown photographer, of a German Luftwaffe ace and his comrades waiting to be called to fight. From the Vietnam War we have David Burnett’s picture of a U.S. soldier leaning against the tank, reading his mail, and an image by Doan Cong Tinh of North Vietnamese guys in hammocks reading their mail.

NZ: But while those comparisons can be found in this exhibition, it wasn’t a preeminent goal of ours to cut down cultural lines.

SN: Certainly in the last couple of wars that we’ve seen, in Iraq and Afghanistan, there’s been a real dearth of imagery from the “other side.”

AWT: I’m sure the images exist; we just haven’t been able to get our hands on them. People say that the system of “embedding” has put such limitations on photographers in Iraq that very few images came out of that conflict. People need to be reminded that there are plenty of Arab photographers working in Iraq.

WM: We also have said from the very beginning that this exhibition would fail if we weren’t true to ourselves and our understanding of photography. Yes, we wanted a balance, but it was most important to make sure that every picture we included was a great picture.

AWT: And there are some things that just don’t get documented. Will and I have looked at more than a million pictures. Interestingly, we’ve found virtually no photographs of hand-to-hand combat.

NZ: And of course for this project we could only pick from what we could actually get hold of. You might find an amazing image on Google but that doesn’t mean you can find a print of it in real life.

AWT: There’s a well-known image, by the Chinese photographer H.S. “Newsreel” Wong, of a child at a railway station in Shanghai in 1937, when the Japanese bombed the city. It’s a canonical image—and we looked everywhere for it; we had people in China looking for prints. No one has a print of that image.

WM: We had to cut it from the show because we couldn’t find it.

SN: Of course, sometimes photographs are created—staged— especially to fill in for documentary images that don’t exist. What does it mean when photography lies in that way? Is there a place for that?

AWT: Well, as long as there is greed, there will be staged photography. The media wants a certain type of picture and those pictures will be made and sold. It’s about supplying something that can’t be supplied otherwise . . . but without courage.

WM: When Wesley David Archer’s book Death in the Air: The War Diary and Photographs of a Flying Corps Pilot came out in 1933— which includes about fifty pictures of an air fight—everybody wanted to see dogfight pictures. But it was a complete hoax. It even included a diary of a pilot—all fake! But people ate it up, because that’s what they wanted to see.

SN: Hah! That’s chutzpah foryou! But good for him: if you’re going to tell a lie, tell a big one. But maybe one of the great things about photography is that it does leave a kind of trail of evidence behind itself ... it has a transparency that other media don’t have. You can go back and look at its footprint and see if it measures up.

WM: In a sense, of course, there’s no “truth” to any kind of photograph: every time a photographer takes a picture, it’s an interpretation of what he or she saw.

SN: Right: the perspective will be different, depending on who’s doing the looking. On that front, WAR/PHOTOGRAPH Y strikes me as quite a male project: it doesn’t have much of a female perspective.

WM: It’s interesting that you say that. At the first education meeting for WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY, there were eighteen people in the room, and I was one of only two men. This project has been run and driven predominantly by women.

SN: We talked about certain types of images that are rarely documented. Here, for example—as well as not having pictures of hand-to-hand combat—there are no pictures of rape.

NZ: There aren’t many out there. We have interviewed photographer after photographer about that.

AWT: One of the most chilling things we found is in the Archive of Modern Conflict in London. It’s from a German soldier’s album from World War II. There are six photographs on the page. One is of a woman lying dead on a haystack with her underpants down around her ankles. Next to it is a picture of a dead cow, and next to that is a dead soldier.

SN: It’s a souvenir album?

AWT: Yes. We actually asked the Archive of Modern Conflict if, in all their millions of pictures, they had one of rape, and they said: “This is the closest we have.” One of the things that fascinated us is that, when an armed person kills an unarmed person—as in Eddie Adams’s image of the execution of a Viet Cong prisoner—the killer often doesn’t seem to care about being photographed, and allows the picture, even invites the picture. With rape, they don’t want the picture. Secondly, the photographers we interviewed about this were very conflicted about being men (we never found a woman photographer who had been in that situation) photographing a scene of rape, exploiting the woman, and not doing something to stop the situation.

SN: The picture exploits the woman a second time.

AWT: That’s right. There is one picture that Philip Jones Griffiths took in a hotel room in Vietnam in 1970, of two men with a woman on a bed . . . but there’s some disagreement about whether she was a prostitute and whether it was really a rape. In our show, we do have pictures of the aftermath of rape, like Jonathan Torgovnik’s recent project about children of rape victims in Rwanda.

SN: There’s a sort of linear arc to the book and the show. It begins with the advent of war, moves to recruitment, and then goes through the training, the wait, the fighting, and then the aftermath and death, and then finally remembrance of the whole thing. It’s like an individual soldier’s journey. So in that sense, is it an exhibition from the male point of view? Surely women, even women soldiers, experience war differently?

NZ: Well, what we’re seeing are productions of particular time periods and the attitudes of those eras.

AWT: We do have an image by Gerda Taro of a woman soldier in the Spanish Civil War, and we have Capa’s photograph of women ambulance drivers.

NZ: We also have work by Caroline Cole, Susan Meiselas, and other women conflict photographers. We have Nina Berman and Alexandra Avakian, who—like yourself, Simon—have chosen to be aftermath photographers. Of course, in the “civilian” sections of the project, there are lots of women. But we tried to get women into the military sections as well when we could.

SN: In a way, all these questions lead to the same thing: I often feel that my own photographs are failures, in that they can never tell the complete story of warfare. Do you think war is photographable? It seems to me that World War I, for example, was probably best covered—in terms of the essence of the experience—by poetry. And arguably the Vietnam War was best covered by fictional films.

AWT: And World War II gave rise to some great novels—like James Jones’s From Flere to Eternity and The Thin Red Line. Also, there are war correspondents. I mean, Ernie Pyle’s writing about World War II made me understand that war in a way that nothing else has.

SN: So ... do you think photography is the right medium to talk about war nowadays?

AWT: Well, Winston Churchill said: “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all those other forms that have been tried.” Photography may be the best tool we have for this. I believe that the single image—the photograph—satisfies a part of our brain that neither poetry nor film satisfies. It’s incomplete, yes. But it’s fixed.

Even if photography is not “the best,” it’s real, and it has a history—and that history has impacted our collective memory of war. Along with books and movies and music, it is a vital presence in the experience of war for people who’ve never actually witnessed it themselves.

WM: I think it’s not a question of photography so much as photographers—it’s not about the image itself; it’s about what the photographer chooses to shoot. And how good the photographer is at translating what is witnessed into his or her own vision.

NZ: WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY isn’t attempting to show “the experience of war” through photography. We’re exhibiting the visual residue of war. The visual captures that have been made of experiences.

SN: I guess my question isn’t so much about what you’ve put on the walls in the show, but a larger question I ask myself: What do I do, going forward from here? I have to think about photographing the current conflicts—and the next one, the one that’s being planned right now. And I wonder whether photography is an adequate tool for doing it.

Of course, people are going at it from different angles. Look at the photography coming out of Syria right now—it’s material shot on cellphones that’s producing all the great images and TV footage. And there are a few people who are considering ways to cover the wars to come—people like Trevor Paglen, who’s thinking about the technology of future warfare: satellites and surveillance and drone systems.

WM: From the general public’s standpoint, photography may still be the most trusted medium. Maybe that’s changing, but for the most part, I think the public thinks that what they see in a photograph is real.

NZ: It’s interesting: we’ve had the opposite of this conversation so many times—about things in the exhibition that are so distinctly photographic. For example, images of destruction after a conflict, or images of the dead after a conflict, or images of wounded people.

SN: I still think, in some ways, that my own reference point for the depiction of war is the first twenty minutes of Saving Private Ryan, which is a piece of immersive work that I find completely overwhelming. I’ve actually seen real combat, but I found the film version more real than real warfare.

WM: After working on this project, I can’t watch war films—I can no longer separate them from reality, as I can with a photograph. I had to force myself to watch Restrepo after Tim Hetherington was killed.

SN: How else has working on this project affected each of you?

WM: I think it is impossible to be completely immersed in war, whether it’s in your backyard, in books, or in video games, and not have it affect you in some way. It is specific to humans and shows human nature at its worst. The only ones who can possibly understand it are those who experience it firsthand. Those of us who haven’t had direct experience of war are intrigued, curious as to who fights and why these wars happen. We try to find a way that we can relate, to understand.

"Plenty of nights, as we worked on this project, I could not sleep because of what we had seen or read that day. But this show is not about my feelings. We have tried to be as evenhanded as possible in our presentation of the views of the two primary components of these pictures— war and photography. What we want from this project is to raise the level of the discussion about conflict photography and its aftermath. The show is not about answers, but questions."

—Anne Wilkes Tucker

NZ: Before working on this project, I tended to read photographs as products of a culture, both in why they were made and how they are published and interpreted. When I started looking at war pictures with Anne and Will, I came to appreciate our varied approaches to images. Anne never fails to acknowledge an image as the work of an individual craftsman, always keeping the photographer in mind, and Will’s ability to respond to an image’s formal qualities, regardless of subject matter, is incredible.

Our different approaches to war and conflicts have been fascinating, too. Anne’s experience of Vietnam is radically different from mine. She lived the protests; I was taught about them from pictures and textbooks. And Will and Anne’s thinking about contemporary conflicts differs from my own also. I came of age post-9/11. I have a younger brother who was deployed to Kunar province (the same year Restrepo was released—not the best thing for my mother). He is home now and training to be an army recruiter. Evidence of conflict is still present.

AWT: I am still basically a pacifist—a person who does not watch violent movies or read violent books—but I now have enormous respect for the men and women who commit their lives to defending their country. If I see someone in uniform in a public place, I thank that person for serving. I’ve gained some knowledge and understanding about a military mindset, history, and training as well as differences in strategies and tactics in warfare.

This project has also been my first in-depth contact with the world of photojournalism. Attending World Press Photo and the Visa pour l’image photojournalism festival has been invaluable, as has meeting all the photographers and editors and interviewing them about what they do. As with the military, my prior understanding was limited regarding the preparation and skill required to be a really good journalist: it requires serious news-gathering skill as well as introspection and creative vision.

Finally, my horror of what humans can do to each other has only increased. Plenty of nights, as we worked on this project, I could not sleep because of what we had seen or read that day. But this show is not about my feelings. We have tried to be as evenhanded as possible in our presentation of the views of the two primary components of these pictures—war and photography. What we want from this project is to raise the level of the discussion about conflict photography and its aftermath. The show is not about answers, but questions.

SN: Again, I think that maybe no matter what the medium— film, photography, poetry, fiction, anything—there is no way for a single work, or even an entire exhibition of work, to convey a complete understanding of war. And even if you had all the possible angles covered, the viewer would bring to the work his or her own perceptions and blindness. I think you’ve done a great job in trying to overcome that gulf, showing so many sides of the subject.

AWT: Thomas Mann wrote: “It is possible for a book to be more ambitious than its author.” Will was presenting some photographs from the show recently, and someone remarked to him that one image “didn’t belong,” because it was taken after the war. And my gut response to that was: War is never over.

NZ: War lasts forever, in terms of sociopolitical impact, governmental policy, intimate emotional experiences.

AWT: And in the damage it does, rending families apart, ruining lives, changing economic realities. War never ends. ©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

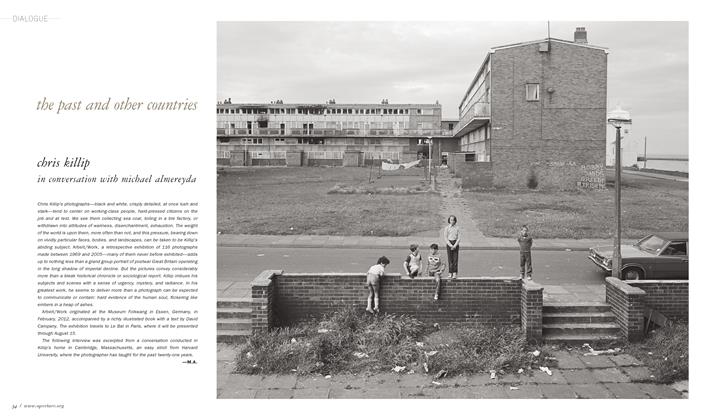

Dialogue

DialogueThe Past And Other Countries

Fall 2012 By Michael Almereyda -

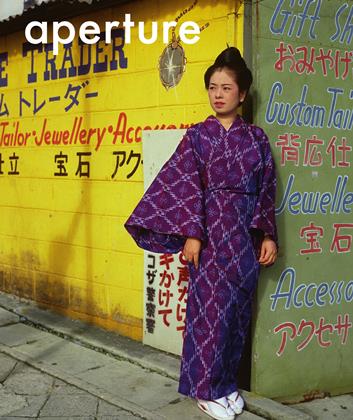

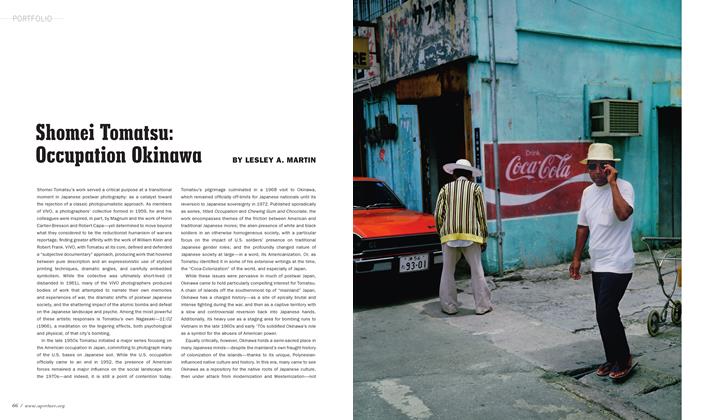

Portfolio

PortfolioShomei Tomatsu

Fall 2012 By Lesley A. Martin -

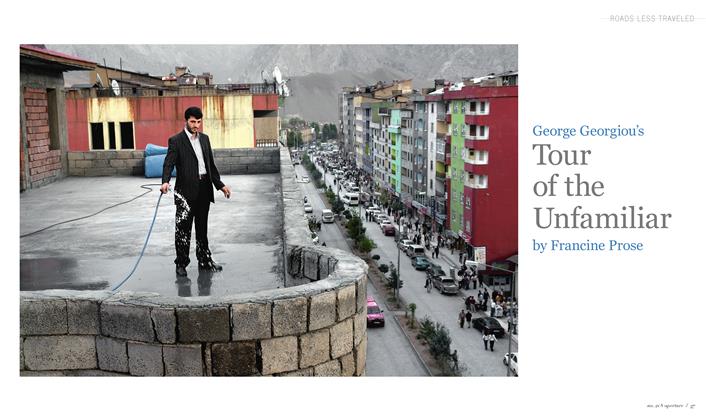

Roads Less Traveled

Roads Less TraveledGeorge Georgiou’s Tour Of The Unfamiliar

Fall 2012 By Francine Prose -

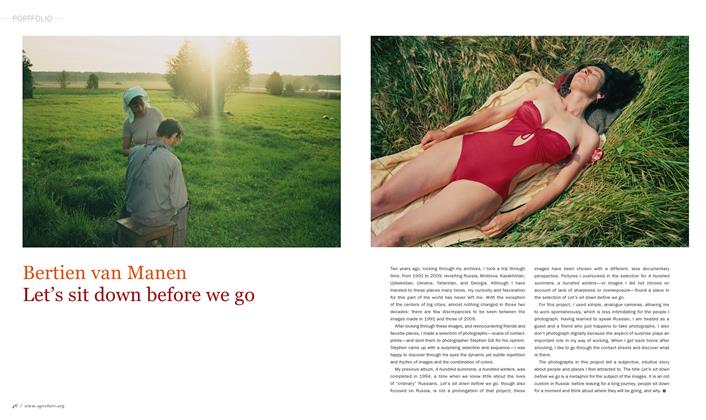

Portfolio

PortfolioBertien Van Manen Let's Sit Down Before We Go

Fall 2012 By Bertien Van Manen -

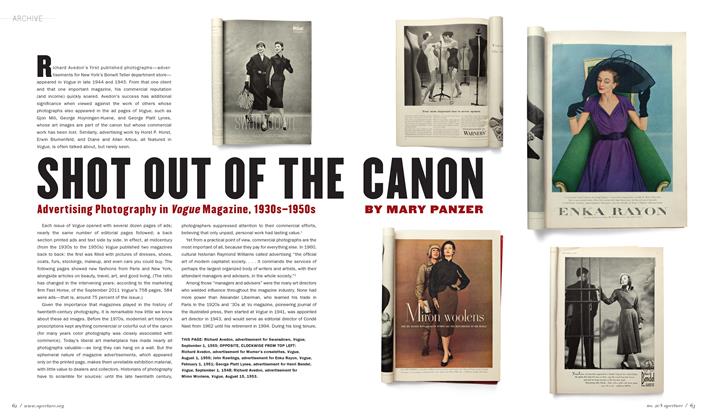

Archive

ArchiveShot Out Of The Canon

Fall 2012 By Mary Panzer -

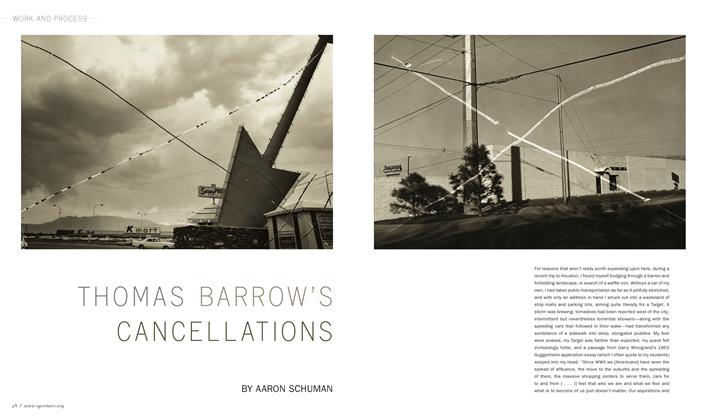

Work And Process

Work And ProcessThomas Barrow's Cancellations

Fall 2012 By Aaron Schuman

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

The Editors

-

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteConnoisseurs And Collections

Summer 1991 By The Editors -

Back

BackObject Lessons

Spring 2014 By The Editors -

Front

FrontPerformance

Winter 2015 By The Editors -

Front

FrontOdyssey

Spring 2016 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteAmerican Destiny

Spring 2017 By The Editors -

Object Lessons

Object LessonsSelf-Portrait By Chief S. O. Alonge, Benin City, Nigeria, Ca. 1942

Summer 2017 By The Editors

Theme And Variations

-

Theme And Variations

Theme And VariationsState Of Exception

Winter 2010 By Ben Sloat -

Theme And Variations

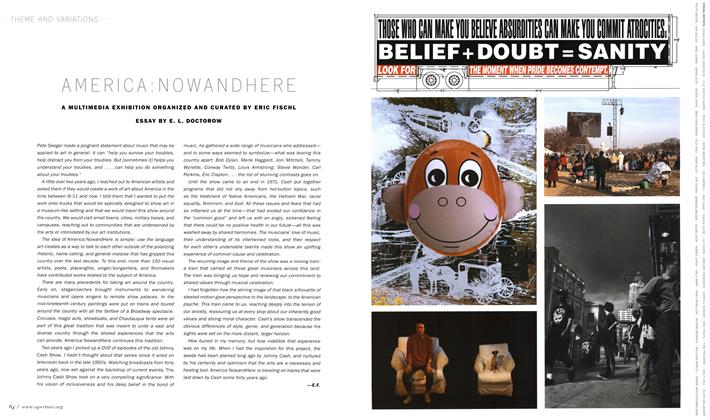

Theme And VariationsAmerica:nowandhere

Fall 2010 By E. L. Doctorow -

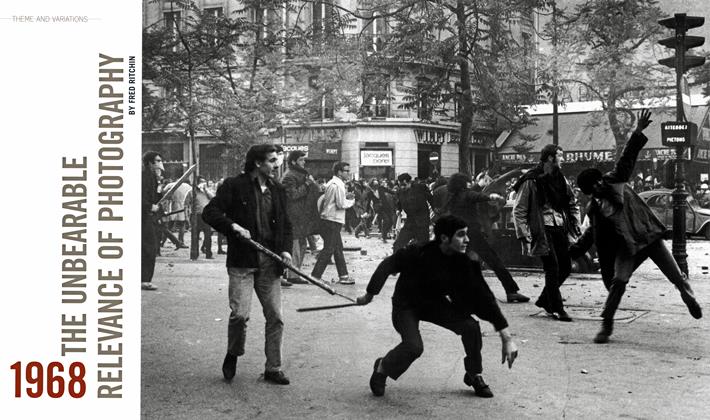

Theme And Variations

Theme And Variations1968 The Unbearable Relevance Of Photography

Summer 2003 By Fred Ritchin -

Theme And Variations

Theme And VariationsLeaving Kansas: A Look At Second Life

Fall 2008 By Fred Ritchin -

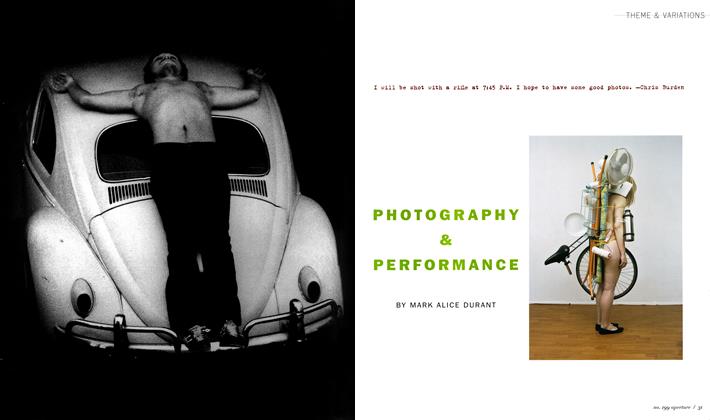

Theme And Variations

Theme And VariationsPhotography & Performance

Summer 2010 By Mark Alice Durant -

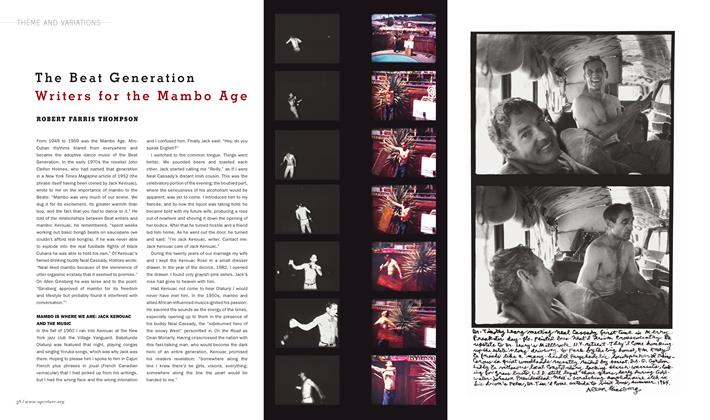

Theme And Variations

Theme And VariationsThe Beat Generation Writers For The Mambo Age

Spring 2012 By Robert Farris Thompson