TALKING PICTURES

DIALOGUE

TOD PAPAGEORGE

JOHN PILSON

Tod Papageorge began photographing in 1962, while a student of English literature at the University of New Hampshire. Since 1979 he has been the Walker Evans Professor of Photography at the Yale University School of Art, where he is the Director of Graduate Studies. That program has generated a who’s who of contemporary photography—Gregory Crewdson, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, KatyGrannan, An-My Lê, and many others—the range of whose photographic approaches testifies to Papageorge’s talent in drawing out his students’ unique gifts.

Two recent monographs focused on bodies of Papageorge’s own photography: Passing Through Eden: Photographs of Central Park (Steidl, 2007) and American Sports (Aperture, 2008). This past spring brought the publication of Papageorge’s Core Curriculum: Writings on Photography (Aperture). On the occasion ofthat volume’s release, Aperture magazine asked John Pilson, a former student and current colleague of Papageorge’s, to speak with him about the new book, his thoughts on gesture and public space, and how he crafted a curriculum that has helped shape some of the strongest photographers of the past three decades.

JOHN PILSON: You’ve just put the finishing touches on a new collection of your writings. Was this simply a matter of “collecting”?

TOD PAPAGEORGE: Based on talks I gave at Yale in 2009, I wrote two long pieces on Eugène Atget (the longest thing I’ve ever written) and Henri Cartier-Bresson; and a shorter text on Brassaï—which centers on a single word that Brassaï used in a letter he wrote to his parents, namely: demonically.

JP: Is he writing in French or Hungarian?

TP: Hungarian. In the context, Brassaï has been asked by his parents if he might consider returning to Hungary, given the terribly difficult first year he’s had in Paris. And Brassaï, who seems the ever-loving son, replies with great anger, saying: “How can you do this to me? Why should I care about the tranquility of my aging parents’ lives, I, who flourish here demonically?” Whoa, man! So my little essay is basically about how that word could have occurred to him and what it might have meant to him, and, more broadly, about the relation of his photography to writing—how central writing is to Brassai’s identification of self. I think it’s certainly the first core identification he had of himself as an artist, even though the writing he was doing at that point was commercial, journalistic. But that activity informed everything, including, eventually, his photography.

JP: Paris played a large part in your own beginnings as a photographer: marathon screenings at the Cinémathèque Française, the politics and theater of the streets. It’s tempting to make connections between what was going on with the French New Wave directors: looking at a medium all mixed up in popular culture, formulating their own ambitions, deciding what to steal and build on. I like to think there were some parallels to the 1960s photography scene in New York. John Szarkowski as the Henri Langlois to a different but related photographic New Wave.

TP: The center of the miracle was Garry Winogrand, who I think, possibly in some kind of response to John’s writings on photography, took it upon himself to try to figure out what photography was, at least as he understood it. That’s when I met him, in late 1965, when he was trying to figure this thing out, which was just about the time that he decided to have a little workshop at his house on Sunday nights, where he would look at our pictures (Joel Meyerowitz was part of this group) and mull over what it all meant. His manner, his style of understanding these things, was purely, utterly Socratic. I’m sure he’d heard of Socrates, but he’d certainly never read a word of Plato. He would just ask question after question after question, as if he didn’t understand anything. And the fact is, he really felt he didn’t understand anything, but— almost urgently, at least as it seemed to me—appeared to believe that something that might help him understand (and of course I’m speaking about photography) was to clarify for himself what the rest of us meant when we said something about it.

JP: During those evenings, were you there to define a project? Were you only focusing on the structure and quality of individual pictures, or were people talking more about their general ambitions?

TP: No. In fact, it was all very abstract, very much like my similar discussions with John Szarkowski. It was never really specific, beyond saying: “That’s a good photograph.” Garry was embarked on an interrogative process: What is a photograph? What does a photograph have to be? Why does it need a level horizon, or does it? That’s what he was working out. The kind of questions that led, for example, to his well-known formulation that anything can be photographed. He would say something occasionally about a specific picture, but usually not more than a sentence, which was about all that John would say about one. The picture was never to be fetishized. It was simply an instrument for learning more in relation to the question of what photography might be. It certainly had nothing to do with projects or anything delimiting. It was simply being out in the world and making photographs to try to understand what this picture-making system was about. I fell right into it. I guess it fit my own sense of things. I didn’t need to be praised for particular pictures, or encouraged. It was all so exciting just to be doing this thing, to be so actively involved with it. Needless to say, it also had very little to do with success in any conventional sense, meaning shows or even work being purchased by a museum. There were so few venues, it didn’t really matter. And it certainly didn’t matter at all in relation to a larger art world. There was no larger art world for photography. There was what John did at MoMA, and that was basically it.

JP: When I started visiting MoMA in the mid-1980s, the photography department still felt very separate. You went and saw the paintings and sculptures, and photography was like the “adult” section in the video store. There was something illicit, like a secret history, or a history apart. I’m curious, were you talking about photography purely in terms of photography, or were you drawing parallels to what else was going on in the art world in painting and film?

TP: No, it had nothing to do with that, although I remember coming out of the big show of postwar painting that Henry Geldzahler curated at the Metropolitan Museum in 1969 or 1970, and Garry saying of painters like Barnett Newman and Kenneth Noland: “Well, yeah, you can put their work above the couch in any luxurious apartment in New York, but you could never put a Goya there.” That’s the way he felt about a lot of the painting of that time, that it was just decorative.

I also remember that I once forced Garry to see a Robert Bresson film—actually, a double feature. This was a guy who could barely stop to drink two cups of coffee in a row, but, at least that night, he sat in the dark long enough to watch, and be blown away by, both films.

Norman Mailer was a hero of Garry’s. He recognized in Mailer a certain wildness that he felt in himself. He was disappointed when Mailer turned down his request for a recommendation for a Guggenheim Fellowship, but honored the reason, which was that Mailer would have had to take a day from his writing to do it.

JP: When I think of Mailer and the “New Journalism”—blurring the lines between the author and the headline—it seems in the same spirit as those photographers, Garry included, who were often standing shoulder to shoulder with journalists doing their job. Your own American Sports project represents an immersion in events, crowds, and spectacle but describes a dark and emotionally complex world.

TP: And people, figures in the space. When I first looked at CartierBresson, first looked at The Decisive Moment, I was interested in the way he handled huge masses of people. In fact, I was amazed by it. Of course, for the most part, he was doing it with a 50-millimeter lens. What was moving me with the Sports project was to make pictures of even more people, using a wider lens to do it, to find out if it was possible—in other words, to make pictures that were both clear and, apparently, intentional.

But you’re right. The emotional thing was central at that time. There’s no describing now how overwhelmed we all were by the Impossibility, it seemed, of the Vietnam War ever coming to an end. I received a Guggenheim Fellowship [to create the American Sports project] only a few weeks before the Kent State incident, where students were shot by the National Guard, a huge inflection point in the whole antiwar protest at that time. So, basically, I was in a rage making those pictures.

JP: You make a related point at the end of your introduction to Winogrand’s 1977 Public Relations, with a long quote from Lionel Trilling on Isaac Babel’s stories based on his experiences in the Red Army. Trilling describes a writer who is providing an almost excessive amount of detail in his description of politically charged, historically calamitous times. The question that Trilling asks is: What use is all this description when the central issues seem to be almost completely neglected?

TP: Well, Trilling’s point in relation to Babel is that the descriptiveness is, in some way, articulating a moral position: when you describe your world so accurately, when you describe what you see so precisely, you’re in effect engaged in the attempt to tell at least a kind of truth.

JP: When I was a student, the big arguments revolved around “the politics of representation”; who you were and what you could say. There was an implied criticism of the Szarkowski tradition, that there were unasked questions in terms of the nature of the “gaze” and privileged positions.

TP: Well, for me it always goes back to the two early CartierBresson photographs that I saw when I was taking a beginning photography class in my last semester of college—the pictures that, then and there, convinced me that I had to be a photographer. Why? Because I saw them as poetry, and nothing else; fiction, and nothing else; inventions, and nothing else. Of course, I’d be a fool not to agree that a photograph represents something described in the world at a certain moment and in a certain place—that, to some degree, it is indexical. In fact, let’s say a large part of its paradoxical strength, and its access to a certain kind of poetic meaning, is precisely because of that. Because we’re looking at the world (or imagine we are) at the same time that any brief thought given to the question will tell us we’re also looking at a representation of it. And my belief in art in general, combined with my profound belief in the power of great poetry, great music, and, yes, great photography, led me even in the beginning to be completely unconfused about what I considered side issues. The question was art, and making art (the game that Robert Frost believed had to be played for “mortal stakes” to be good) is a practice that leaves no time for niceties. It was never an issue of “identity and questions of representation” for me. Because it was never about what somebody was going to think in ten years, or an

art historian in thirty years: I took the longest possible view. That was always my attitude. I’m not saying that I always have been and always will be completely right—but I believe that, in relation to this particular question, I was and still am. That gave me, I think, a certain kind of resilience in relation to what I felt were incidental, if not uninformed, questions.

JP: Your Central Park photographs [Passing Through Eden] began with the simple fact that you found yourself having to cross the park almost daily. It seemed important: routine and repetition as integral to the process. I think it’s interesting how, in sprawling cities like Athens, Paris, and Rome, you re-create this process of committing to a relatively narrow part of the city, and revisiting that space day after day after day.

TP: That’s an interesting point. I’ve never really thought about it. I think my attraction to these cities has something to do with that. As much as I am an American photographer, I find in places like the Acropolis in Athens, or Rome, or Paris, a certain kind of beauty that is central to my sense of aesthetic satisfaction. But I’d say there’s also a lot of beauty in the Central Park book, if only in the figures, in the bodies, and so forth.

(continued on page 78)

(Papageorge continued)

JP: But if you’re the master of anything, you are a master of gesture, of the observed, casually athletic tensions of public spaces. You once mentioned one of Winogrand’s rare assignments for students was to “photograph someone doing something to someone else.” Your pictures are filled with individuals intersecting, reaching out, negotiating space.

TP: It’s part of the system of the form, the sewing-together of the form, which becomes a part of the meaning, of course. So in a way, the viewer is to some degree relieved of interpreting the picture. The viewer’s only responsibility is to feel the gestural wholeness of the picture. Not that I’m trying to relieve the viewer of any responsibility, but it gets back to a remark you made earlier. These pictures aren’t about implication, in the sense that if you look at it from the right angle with the right sense of reverence, you’re going to figure out what it was supposed to mean. It shows you what it means, right there, through the gesture.

JP: One of the things that you do consistently is create relationships between people who have nothing to do with each other. This seems to me one of the great opportunities of public space for a photographer.

TP: This is central to what we were all trying to do back then in the ’60s. I think that one source of the frustration I’ve always felt about the eventual supremacy (at least for a moment) of postmodernism, and even about staged photographs—which was something nobody seemed able to understand (outside of Szarkowski, but certainly no art historians and certainly no editors at October magazine)—is that we knew we were making fictions. We knew we were creating something, in many cases, out of nothing. Or nothing more than the conjunction of objects and people in space. The unspoken expectation was that an intelligent person would look at something like what you described and say: “Well, obviously that never happened. The photographer has, in effect, through perception and response and training and whatever else (such as a poetic presentiment), created this, this made thing, this piece of art.” Now, perhaps you’re not interested in it as art. Perhaps you don’t think it’s as wonderful as a James Rosenquist painting or something else. Yet it is art, something fabricated out of the unfabricated dross of passing life (while, paradoxically, still trading on the indexical heft of that dross). Unfortunately, however, it turned out that most people needed to see the literal lineaments of fabrication—the studio effect—to recognize that art-making had occurred. I’ve always believed, in fact, that it was a terrible relinquishment on the part of the so-called “intelligent audience” not to be hard enough on itself to understand that, but of course I would believe that, given my position as a photographer-in-the-world. It’s been a decades-long frustration, though, and I guess always will be one, because people tend to see photographs as simple, literal recordings of the way things were at a particular moment unless—these days, through scale, color, and a certain residual sense of the embalmed that the studio and Photoshop often lend to them—they effectively brand themselves as having been deliberately manufactured.

JP: I’ve seen you bristle at the terms street photography and the snapshot aesthetic.

TP: Right. The first article in the new book is a little essay—the first thing I ever wrote on photography—on the snapshot. Really, it’s a covert argument against the notion of what we were doing as having anything to do with “snapshots.” In fact, it argues at one point that somebody like Edward Weston was actually closer in spirit to family albums, and vernacular photography, than we were.

JP: The new collection of writings is titled Core Curriculum, which I suppose is, in part, a reference to your career as a teacher. Which brings us to teaching.

TP: These are the hardest questions for me.

JP: Yale represented the chance to shape a curriculum.

TP: Mmm-hmm.

JP: Can you remember some of your initial thoughts about the kind of program you wanted to design?

TP: My immediate answer is no. But just last week, I received in the mail a long article written by the photographer, Jerry Thompson. He was on the faculty at Yale when I started teaching there, and, very generously, I must say, describes me [at Yale in 1979] working out, through what I’m saying about photography and the students’ pictures, a kind of notional structure that will help them understand how they might go about making what I called, and I suppose still call, “interesting photographs.” It had to do with the way pictures look, and complication, and, especially, the frame—the relation of the frame to what it held, and the way it held it. Because, as we know, if left to themselves, people tend to make dull pictures without really thinking about what they’re doing. So I guess I was actively doing something with my teaching, even way back then, although I wouldn’t have claimed to be doing anything in particular at all.

And I guess I also I had this thing, even then, which I feel I still have: I professed. I was a professor and was one from the first day I taught, professing my love of photography—perhaps, in the beginning, much more than my actual understanding of it. And the students never failed to recognize that. They realized that I took this thing very seriously, which led a lot of them to think that they might, too. ©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Essay

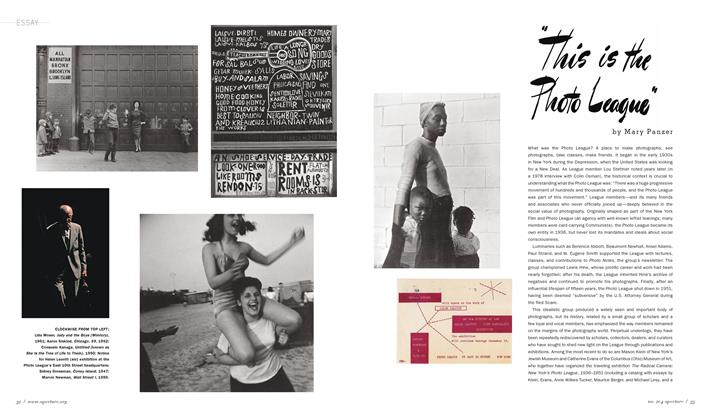

Essay"This Is The Photo League"

Fall 2011 By Mary Panzer -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessAn Atlas Of Decay: Cyprien Gaillard

Fall 2011 By Brian Dillon -

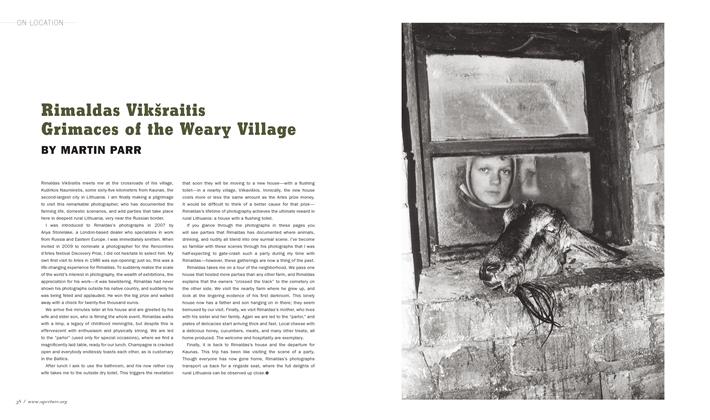

On Location

On LocationRimaldas Vikšraitis: Grimaces Of The Weary Village

Fall 2011 By Martin Parr -

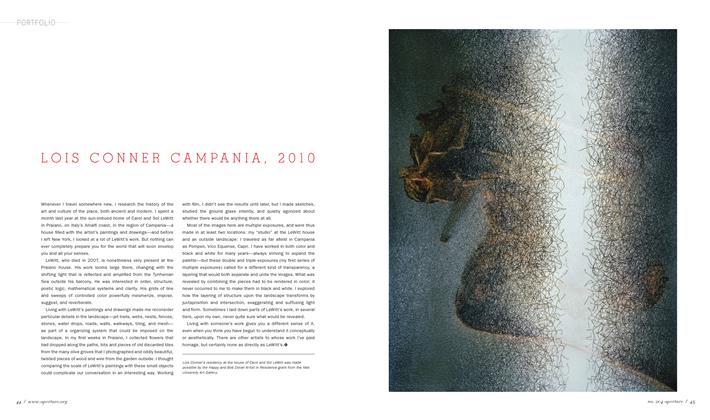

Portfolio

PortfolioLois Conner: Campania, 2010

Fall 2011 By Lois Conner -

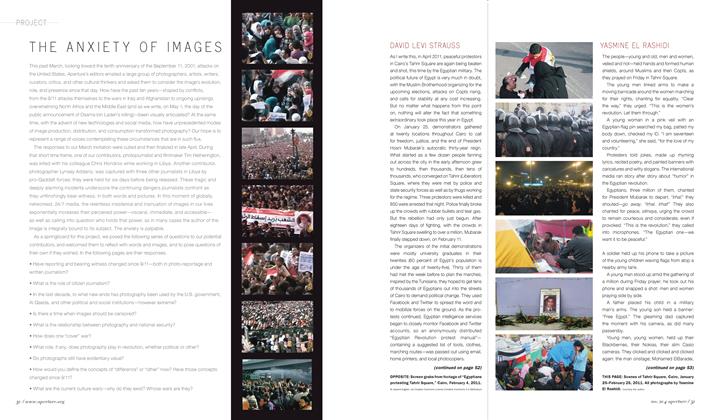

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesAbigail Solomon-Godeau

Fall 2011 By Abigail Solomon-Godeau -

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesYasmine El Rashidi

Fall 2011 By Yasmine El Rashidi

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Dialogue

-

Dialogue

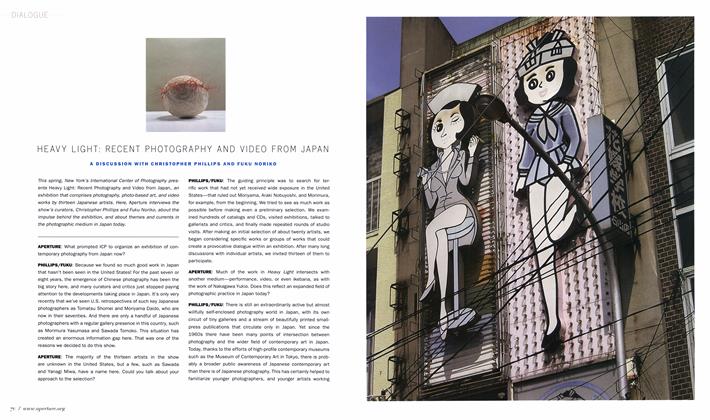

DialogueHeavy Light: Recent Photography And Video From Japan

Summer 2008 -

Dialogue

DialogueThe Knight's Move: A Conversation With Paul Graham

Summer 2010 By Aaron Schuman -

Dialogue

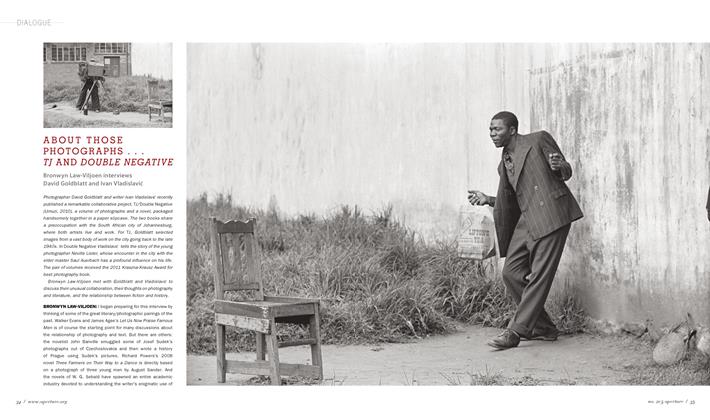

DialogueAbout Those Photographs... Tj And Double Negative

Winter 2011 By Bronwyn Law-Viljoen -

Dialogue

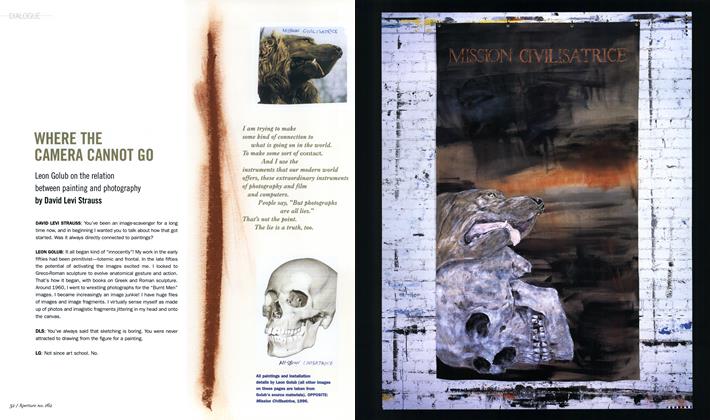

DialogueWhere The Camera Cannot Go

Winter 2001 By David Levi Strauss -

Dialogue

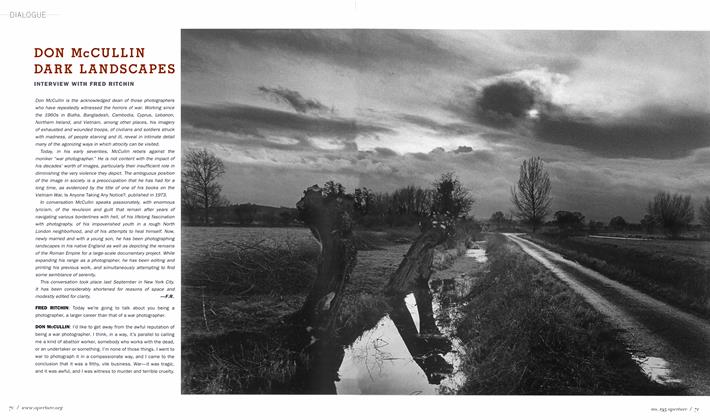

DialogueDon McCullin: Dark Landscapes

Summer 2009 By Fred Ritchin -

Dialogue

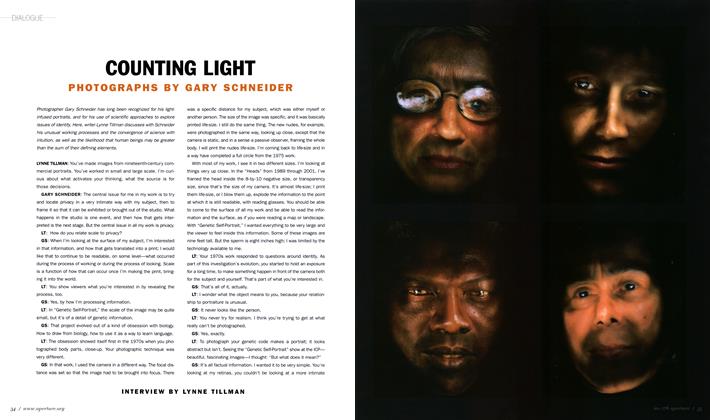

DialogueCounting Light

Fall 2004 By Lynne Tillman