FLESH AND BONE

WORK AND PROCESS

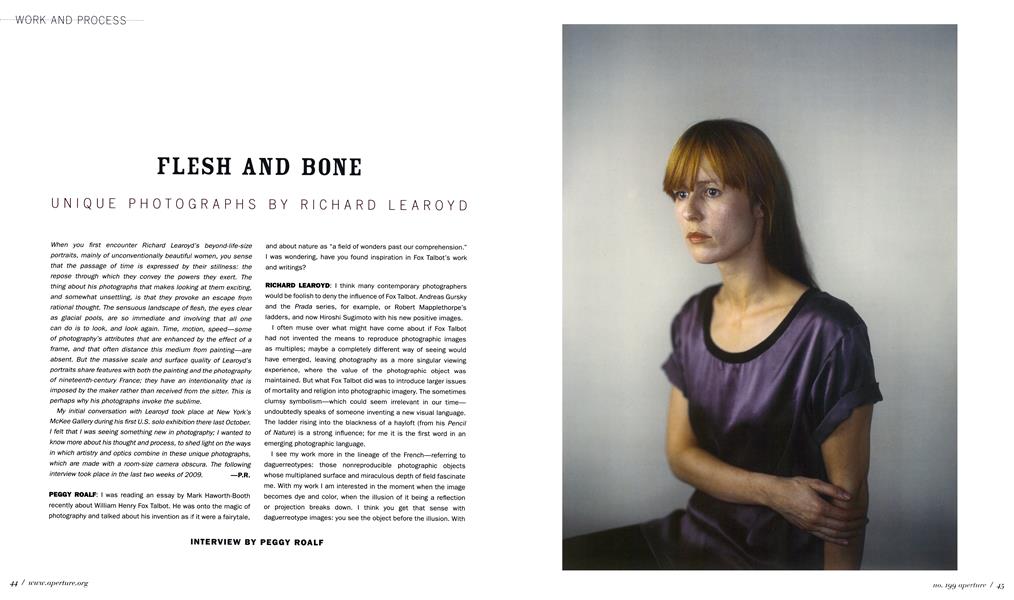

When you first encounter Richard Learoyd's beyond-life-size portraits, mainly of unconventionally beautiful women, you sense that the passage of time is expressed by their stillness: the repose through which they convey the powers they exert. The thing about his photographs that makes looking at them exciting, and somewhat unsettling, is that they provoke an escape from rational thought. The sensuous landscape of flesh, the eyes clear as glacial pools, are so immediate and involving that all one can do is to look, and look again. Time, motion, speed—some of photography’s attributes that are enhanced by the effect of a frame, and that often distance this medium from painting—are absent. But the massive scale and surface quality of Learoyd’s portraits share features with both the painting and the photography of nineteenth-century France; they have an intentionality that is imposed by the maker rather than received from the sitter. This is perhaps why his photographs invoke the sublime.

My initial conversation with Learoyd took place at New York’s McKee Gallery during his first U.S. solo exhibition there last October. I felt that I was seeing something new in photography; I wanted to know more about his thought and process, to shed light on the ways in which artistry and optics combine in these unique photographs, which are made with a room-size camera obscura. The following interview took place in the last two weeks of 2009. —P.R.

PEGGY ROALF: I was reading an essay by Mark Haworth-Booth recently about William Henry Fox Talbot. He was onto the magic of photography and talked about his invention as if it were a fairytale,

and about nature as “a field of wonders past our comprehension.” I was wondering, have you found inspiration in Fox Talbot’s work and writings?

RICHARD LEAROYD: I think many contemporary photographers would be foolish to deny the influence of Fox Talbot. Andreas Gursky and the Prada series, for example, or Robert Mapplethorpe’s ladders, and now Hiroshi Sugimoto with his new positive images.

I often muse over what might have come about if Fox Talbot had not invented the means to reproduce photographic images as multiples; maybe a completely different way of seeing would have emerged, leaving photography as a more singular viewing experience, where the value of the photographic object was maintained. But what Fox Talbot did was to introduce larger issues of mortality and religion into photographic imagery. The sometimes clumsy symbolism—which could seem irrelevant in our time— undoubtedly speaks of someone inventing a new visual language. The ladder rising into the blackness of a hayloft (from his Pencil of Nature) is a strong influence; for me it is the first word in an emerging photographic language.

I see my work more in the lineage of the French—referring to daguerreotypes: those nonreproducible photographic objects whose multiplaned surface and miraculous depth of field fascinate me. With my work I am interested in the moment when the image becomes dye and color, when the illusion of it being a reflection or projection breaks down. I think you get that sense with daguerreotype images: you see the object before the illusion. With my pictures, the illusion is very strong and breaks suddenly, and often only momentarily, which is something I like.

PEGGY ROALF

PR: The nature of film photography today generally excludes any sense of the surface from its describable qualities. When and how did you realize that you could bend traditional photographic processes to create the sense of mass and volume that’s evident in your photographs?

RL: I was lucky enough to be in the generation before computers became the norm. I studied at Glasgow School of Art under Thomas Joshua Cooper, who is a wonderful landscape artist. During that time the frontier seemed to be a place of ideas realized with persistence and craft, where all was valued until proved useless. I look back at the time I had there and realize that’s when my life really began.

I first started experimenting with the camera obscura, or the room-camera method that I use now, during my postgraduate year at Glasgow. It was Cooper who lent me the lens from a nineteenth-century portrait camera he had in his office. At the time postgraduate students were given studios; this enabled me to experiment with a different set of ideas instead of being out in the world searching for something to photograph. Until then, my work had been landscape-based; it was fairly quiet and thoughtful, almost reticent in a way. I suppose something in me craved a sense of power or directness in my work that I felt was lacking in my landscape photographs. Working with the camera obscura seemed to satisfy this need.

For the next several years I taught photography at a university and worked as a commercial photographer. At a certain point I had learned what I could from that and it was time to get on with being an artist. In 2004 I built the first version of the camera I use now, as an extension of the work I had begun fourteen or so years earlier. But now I knew what I was doing. I was inventing photography for myself in a way that I could, and began making the photographs I had imagined could be made. I don’t know why, but the camera obscura seemed to me the most natural of methods. The apparatus I use consists of a lens, some lights, and a processing machine. The process has certain built-in qualities to do with physics and optics, but the most important quality for me is that it is capable of producing photographs that fascinate me, that match my vision.

It is an incredibly restrictive process and there are many things you simply can’t do. It’s slow and painstaking, with much that can go wrong. The method gives parameters of what you choose to photograph. It’s very liberating to have limited choices, and the technique offers immediacy as it jumps past the printmaking process.

PR: At one point you mentioned that people in charge of their bodies, such as dancers, seem to have a different center of gravity. Flow does this observation manifest in your work?

RL: One thing that this process, at best, can do is to translate weight, density, and mass—not only in a physical sense, but in a more psychological way. When a picture is successful, the mental state of the sitter seems to radiate from that person’s physicality.

PR: The surface quality of your photographs is remarkable, in its sharpness, and in the way that you adjust the focal plane to shift back and forth within an extremely shallow range. Can you point to a moment when you found that this was possible on a large scale?

RL: While I must admit to disliking the use of shallow focus in most conventional photographs today (it seems like a device within a device), I think a big influence on my understanding how the focus issue could work for me was revisiting some early Lewis Baltz pictures of scrubland. Don’t ask me why, but they stuck in my mind. The minute depth of field in these pictures is part of a restrictive practice; it’s quite simply physics. Every artist, whatever their medium, has to deal with the rules of the universe. I think the secret is to accept it and move on. For me, in my work, the implication or meaning of this shift between extreme sharpness and blur is an emerging and submerging of a person’s consciousness, and emphasis of their immediate presence.

Learoyd’s portrait of a nude man, Richard on Armature (2007), shatters the silence created by the women in this artist’s prospect. In its formality, the pose is not unlike those of the women, whose flesh and bone seem relaxed, as if settled into place by gravity's pull. But the twisting of the legs, the subject’s slight incline toward the viewer, the intensity of his outward gaze, suggest that the man’s consciousness has been usurped by a powerful memory. The emotion conveyed is raw, almost palpable. Is this a metaphorical selfportrait? I wondered why Learoyd imposes such different demands on the men that he places before hls lens. His response:

I think that maybe my search for detail or perfection in photographs is a desire to illuminate imperfection and humanness. The invitation to scrutinize another, which is undoubtedly in my work, inevitably highlights the loneliness of the soul and the depressing isolation of the human condition. After all, who do we get to look at so closely, so carefully that the pores of their skin and the meniscus of liquid under their eyes are visible? It is the opportunity to look without embarrassment—as we do with our children or lovers. Perhaps I differentiate between men and women in that I am drawn to a more profound intimacy with women, and seem to see men as more physical beings. The barrier of the photographic surface mimics the distance I feel from others and my frustrations with the desires I have for intimacy.©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Dialogue

DialogueThe Knight's Move: A Conversation With Paul Graham

Summer 2010 By Aaron Schuman -

Portfolio

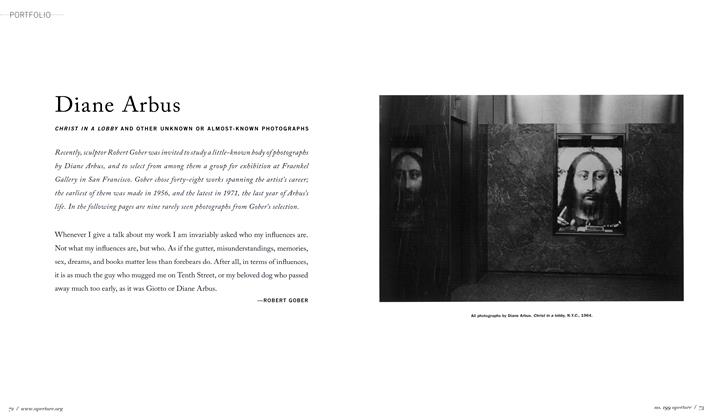

PortfolioDiane Arbus: Christ In A Lobby And Other Unknown Or Almost-Known Photographs

Summer 2010 By Robert Gober -

Mixing The Media

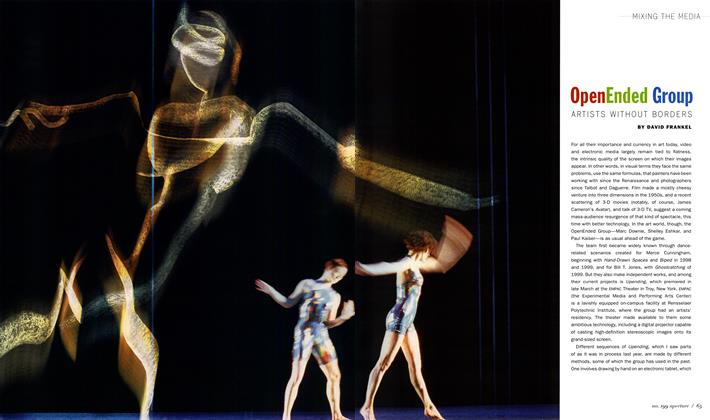

Mixing The MediaOpen Ended Group: Artists Without Borders

Summer 2010 By David Frankel -

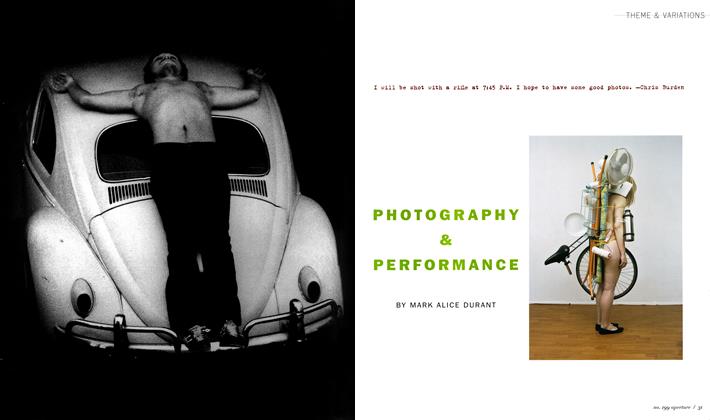

Theme And Variations

Theme And VariationsPhotography & Performance

Summer 2010 By Mark Alice Durant -

On Location

On LocationPiemonte: Koudelka

Summer 2010 -

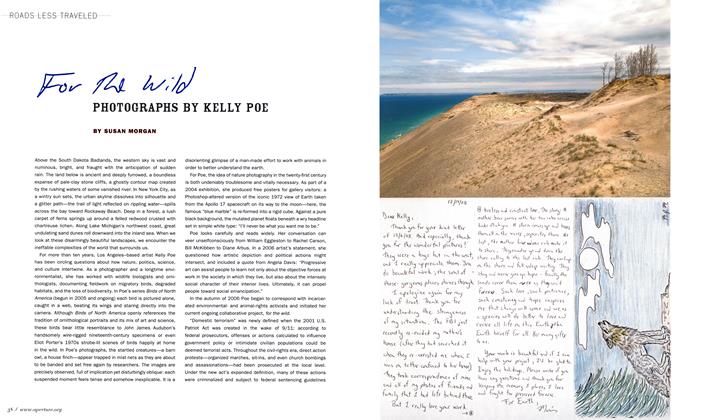

Roads Less Traveled

Roads Less TraveledFor The Wild: Photographs By Kelly Poe

Summer 2010 By Susan Morgan

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Peggy Roalf

Work And Process

-

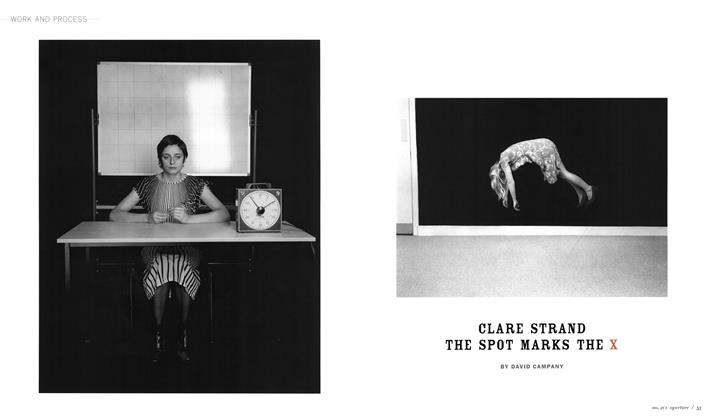

Work And Process

Work And ProcessClare Strand The Spot Marks The X

Fall 2010 By David Campany -

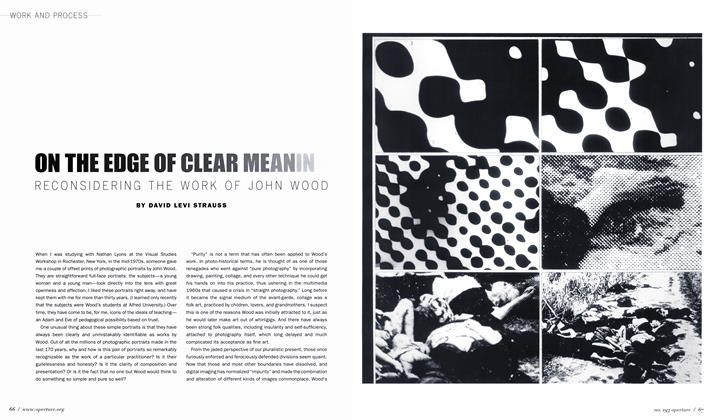

Work And Process

Work And ProcessOn The Edge Of Clear Meanin

Winter 2008 By David Levi Strauss -

Work And Process

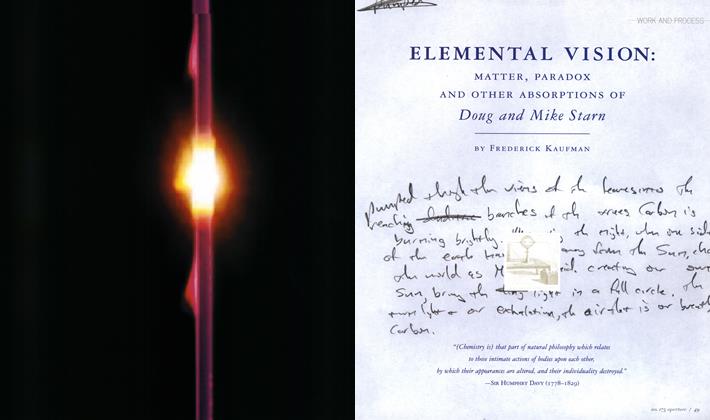

Work And ProcessElemental Vision: Matter, Paradox And Other Absorptions Of Doug And Mike Starn

Summer 2004 By Frederick Kaufman -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessWalead Beshty Piece By Piece

Fall 2008 By Jan Tumlir -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessHiroshi Sugimoto: Enigmatic Objects

Spring 2005 By John Yau -

Work And Process

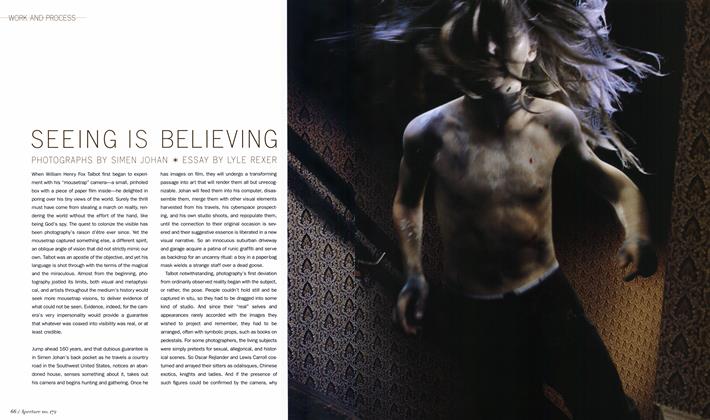

Work And ProcessSeeing Is Believing

Fall 2003 By Lyle Rexer