damage incurred

WITNESS

Don McCullin

Diana C.Stoll

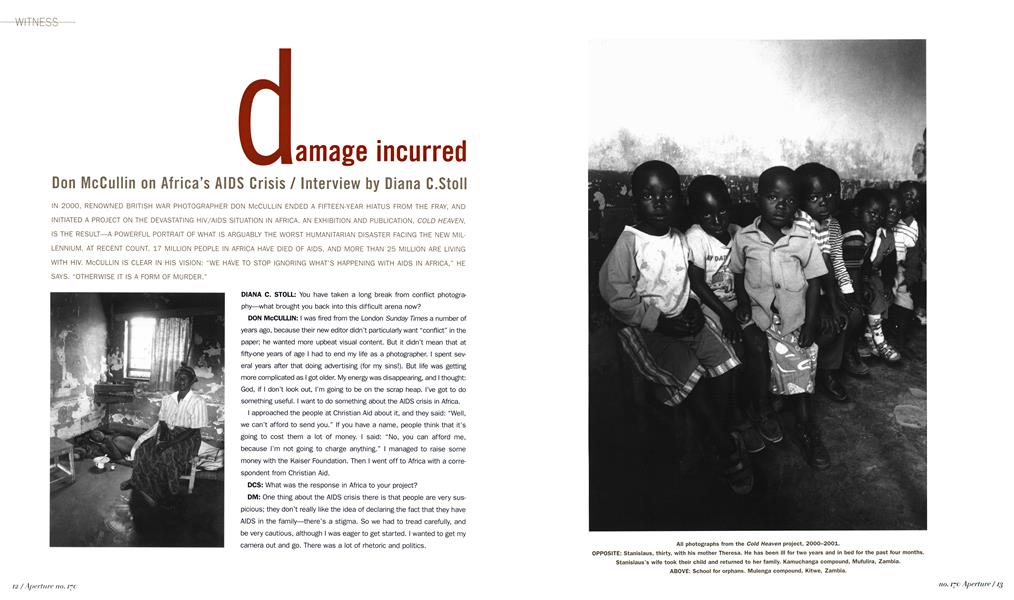

IN 2000, RENOWNED BRITISH WAR PHOTOGRAPHER DON McCULLIN ENDED A FIFTEEN-YEAR HIATUS FROM THE FRAY, AND INITIATED A PROJECT ON THE DEVASTATING HIV/AIDS SITUATION IN AFRICA. AN EXHIBITION AND PUBLICATION, COLD HEAVEN, IS THE RESULT—A POWERFUL PORTRAIT OF WHAT IS ARGUABLY THE WORST HUMANITARIAN DISASTER FACING THE NEW MILLENNIUM. AT RECENT COUNT, 17 MILLION PEOPLE IN AFRICA HAVE DIED OF AIDS, AND MORE THAN 25 MILLION ARE LIVING WITH HIV. McCULLIN IS CLEAR IN HIS VISION: “WE HAVE TO STOP IGNORING WHAT’S HAPPENING WITH AIDS IN AFRICA,” HE SAYS. “OTHERWISE IT IS A FORM OF MURDER.”

DIANA C. STOLL: You have taken a long break from conflict photography—what brought you back into this difficult arena now?

DON McCULLIN: I was fired from the London Sunday Times a number of years ago, because their new editor didn’t particularly want “conflict” in the paper; he wanted more upbeat visual content. But it didn’t mean that at fifty-one years of age I had to end my life as a photographer. I spent several years after that doing advertising (for my sins!). But life was getting more complicated as I got older. My energy was disappearing, and I thought: God, if I don’t look out, I’m going to be on the scrap heap. I’ve got to do something useful. I want to do something about the AIDS crisis in Africa.

I approached the people at Christian Aid about it, and they said: “Well, we can’t afford to send you.” If you have a name, people think that it’s going to cost them a lot of money. I said: “No, you can afford me, because I’m not going to charge anything.” I managed to raise some money with the Kaiser Foundation. Then I went off to Africa with a correspondent from Christian Aid.

DCS: What was the response in Africa to your project?

DM: One thing about the AIDS crisis there is that people are very suspicious; they don’t really like the idea of declaring the fact that they have AIDS in the family—there’s a stigma. So we had to tread carefully, and be very cautious, although I was eager to get started. I wanted to get my camera out and go. There was a lot of rhetoric and politics.

Finally, I was allowed to go—and I went off with a group of ladies singing “We Are Marching With Jesus” as they walked through these African villages. But you knew you were eventually going to arrive at a hut, where you’d find some poor creature dying on the floor. And that’s exactly what I found. You smelled the people before you saw them; the smell of their death was horrendous. Going into these dark huts, you couldn’t see anybody, and it took time for your eyes to adjust—and then suddenly you saw there was a human being there.

It was very disturbing. I started regretting, almost, my decision to come and do this.

DCS: Did they find it strange that you were coming into their homes?

DM: Well, / found it strange, actually. I’d thought I’d given this up, but here I was again, looking at dying people. And what does that say about me? Is this healthy? Is this right?

DCS: Africa has been undergoing so much turmoil on so many levels—wars, famine, abuse—in recent years. Why did you choose to focus on the AIDS crisis?

DM: From 1955 up until a couple of years ago, I’ve seen incredible calamities in Africa. I was there during the Maumau crisis in Kenya. I’ve seen the white man massacring the black man, and I’ve seen Africans killing Africans. But even all that violence is nothing compared with what the AIDS epidemic has done. That’s the tragedy about AIDS, it’s on such a mammoth scale that it’s almost impossible to comprehend the devastation. It is genocide. There is talk of 25 million people dying of the disease in Africa within the next ten years. So what I did with this project was a drop in the ocean. It was nothing—not a movement of the eyelid.

DCS: Another problem is that a lot of people in the media—particularly in the United States—don’t want to look at AIDS anymore.

DM: Right: Aperture is doing this, which is great, but we need to be talking about it in the New York Times. But at the end of the day, you just have to keep picking away. One trouble about the AIDS crisis is that it is possibly the most unattractive story there is—that’s one reason why no one wants it anymore.

DCS: A number of photographers who went into death camps after the World War II said that they photographed but couldn’t comprehend—couldn’t really look at those images until much later. Have you ever had that sense of the camera as a kind of buffer between you and what’s in front of you?

DM: What happens is this: you start off an ambitious young man, and you get involved in photography. Then you’re drawn to conflict, and the more you’re drawn into conflict, the more damage it does to you.

So one day you’re this man, and the next day you’re another. When you’re standing in front of a dying person, you have the

privilege to walk away and get a meal, or see a doctor, or get on an airplane and go away from this terrible place.

DCS: A kind of unnatural detachment.

DM: I don’t think you can be detached, really. I’ve come away from those places each time with a little piece of damage-damage multiplied by damage. It has made me a terrible cynic. I feel shabby—because I’ve made a name, quite a good name, out of photography. And I still find myself asking the same questions: Who am I? What am I supposed to be? What have I done?

DCS: Has your sense of what can be accomplished by photography changed?

DM: I would say I haven’t accomplished one iota of change. Absolutely zero.

DCS: It’s amazing that you can go back into the fray again.

DM: I’ve done it twice since I “gave up” war photography. I went to Iraq during the war there, I went north with the Kurds. I saw children who’d been hit by a shell, and I thought: Fool! Why are you here? You don’t like this anymore, why are you here?

I’m like an old junkie, in a way. You don’t stick syringes in your arm—you go straight for the most important part of your body, the brain. You are destroying it the moment you go to your first war.

DCS: Why do you think there are so many journalists out there doing it?

DM: I think it’s because we are no longer living in an atmosphere of concerned media. It’s hit-and-run media now: they get a story, they build it up big, and then they dump it. Then they move on to the next story.

Also, most young photographers today seem to think that war is the place to be. People think it is glamorous. There’s nothing glamorous at all about going to war—it’s possibly the most unglamorous experience anyone will ever have.

DCS: We have a public with a shorter attention span, also. Everything has been edited down to three-second spots— images come swarming at us all the time.

DM: I think you’re right. When I was in Beirut, I was in a hospital that had been shelled. There were twenty dead people around me, an awful scene. ... I remember hearing the NBC and CBS people come in, shoot two or three moments of the scene, and then run off, saying: “It’s prime time! It’s prime time!” I knew I could screw those people into the ground, visually, and be better than them, because I would stay there. I would stay there hour after hour, and see how things developed and evolved.

I don’t want to be part of what people call the “media circus.” I saw it grow from two or three dozen correspondents, in the early sixties, to a thousand in Middle East wars. And I thought: I can’t work with a thousand people. I’ve always worked alone. I’ve always stood on my own little piece of ground, and exercised my own dignity. You can’t focus when you’re part of that hysteria.

That’s why, I suppose, my time came to an end when I was fired from the Sunday Times. But in many respects, that may have kept me alive, because if I had continued to go to war, I would eventually have been killed. And I actually kind of like living, you know? It’s kind of nice. I’m still alive.

DCS: It sounds as though you are still energized by doing this.

DM: Well, I’ve dropped my anger. And I’m strong. I once said to somebody: “If I went to a psychiatrist, I’d make him pay me for the visit.” They wouldn’t believe the things I could tell them about what I had done. And yet, at the end of the day, any normal, well-educated, sophisticated person—which I’m not— would have surely had mental breakdown after breakdown.

I’ve never walked away from anything without compassion. I’ve always had a decent human streak in me, so when I went into those AIDS situations in Africa, I came away shaken by the disgust of thinking someone could die on the floor—not even in a bed, not even in a hospice.

DCS: In a debate at London’s Whitechapel Gallery on “Photographing AIDS,” one speaker felt that your photos on the African AIDS crisis didn’t show “the hope and the courage and the heroism that you meet on a daily basis” there. Your work is often accused of being dark—of looking dark and representing only darkness.

DM: My pictures are dark. I have a reputation for being dark and printing dark things. I see dying and death as a darkness trip. Maybe I should be more optimistic—but I’ve seen so much cruelty, it’s difficult for me to be optimistic.

DCS: You once said: “Photography has been very, very generous to me, but at the same time has damaged me.” Do you still believe that?

DM: Yes. You know, I was never much interested in making money; I wanted to make great pictures. But then when I think about “great pictures”—when they’re at the expense of other people’s lives—I think it’s rather nasty and sad. It’s hard to put them in the right context.

DCS: Do you ever wish you had never started photographing?

DM: No, I don’t. I came from a very poor background in North London. I left school at fifteen, and used to hang around with gangs. I could barely read. It was photography that gave me a life—it was a huge gift to me. I’ve brushed shoulders with people who’ve really enlightened me; I’ve used them as my mentors.

But there’s always a price. You don’t jump on a bus expecting a free ride. I’ve paid the ticket of life. The amount of disturbance that’s gone on in my mind, the emotions ... I can’t always handle that fully. But I’m strong, you know? Because I believe in myself.

DCS: Are you going to spend more time on the AIDS project, or will you now focus on other things?

DM: I’m going to spend my time now working on a project with the people in Southern Ethiopia. There are many tribes there; some are nomadic and others are cattle-herders. They’re very beautiful people, but on the fringe of being destroyed culturally.

The other project I’ve got is trying to stay alive as long as I can. I’m sixty-seven in October [2002].

I like photographing the English landscape in the winter, because it’s naked and it’s cold and it’s lonely, and I feel lonely doing it—and, yes, I feel as happy as anything. There’s no politics, there’s no one saying: “Get off my land!” No one pointing a gun at me. It’s almost as if I’m drinking from the flower, as if I’m drinking the pure nectar of freedom. ©

“Cold Heaven: Don McCullin on AIDS in Africa" was presented at London’s Whitechapel Gallery, May 24-June 10, 2001, and at the United Nations headquarters in New York, June-August 2001. McCullin is affiliated with Contact Press Images.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Essay

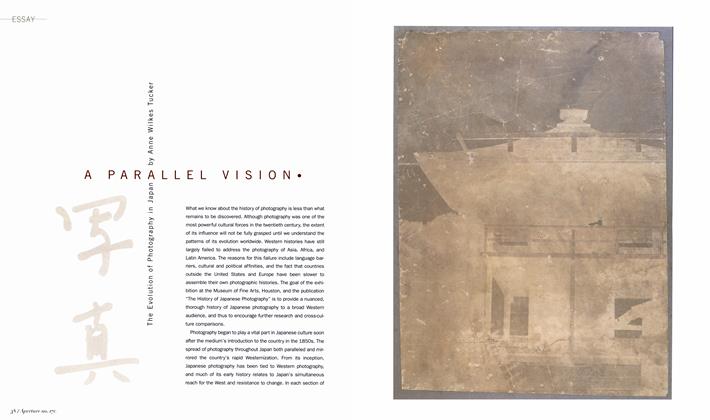

EssayA Parallel Vision: The Evolution Of Photography In Japan By Anne Wilkes Tucker

Spring 2003 By Anne Wilkes Tucker -

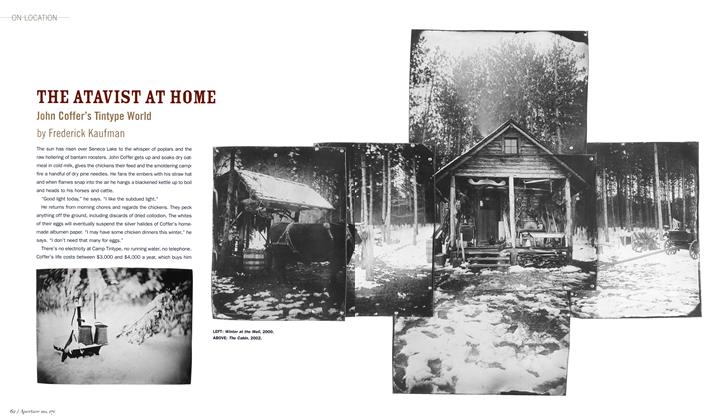

On Location

On LocationThe Atavist At Home: John Coffer's Tinytpe World

Spring 2003 By Frederick Kaufman -

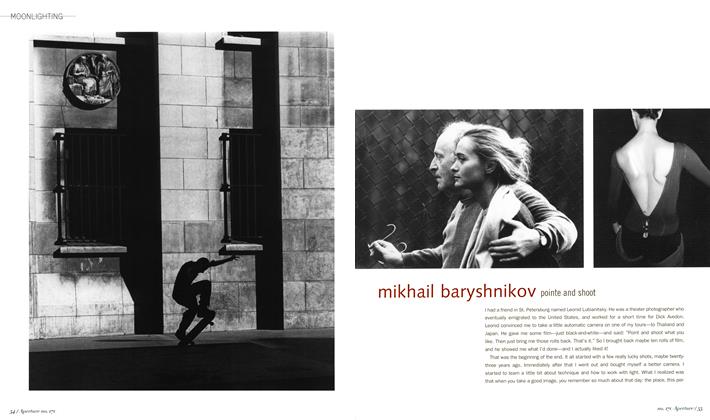

Moonlighting

MoonlightingMikhail Baryshnikov: Pointe And Shoot

Spring 2003 By Melissa Harris -

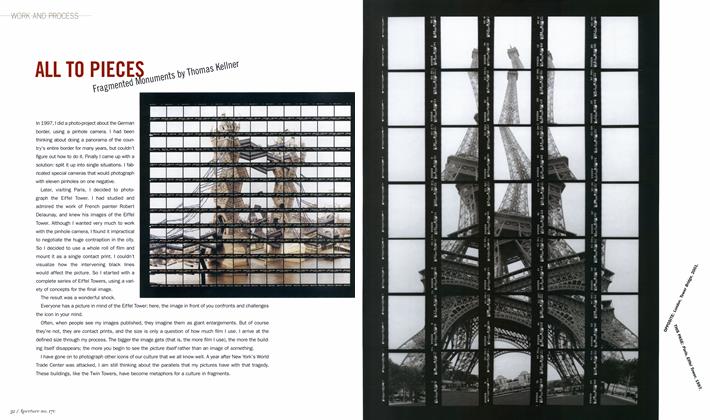

Work And Process

Work And ProcessAll To Pieces: Fragmented Monuments By Thomas Kellner

Spring 2003 -

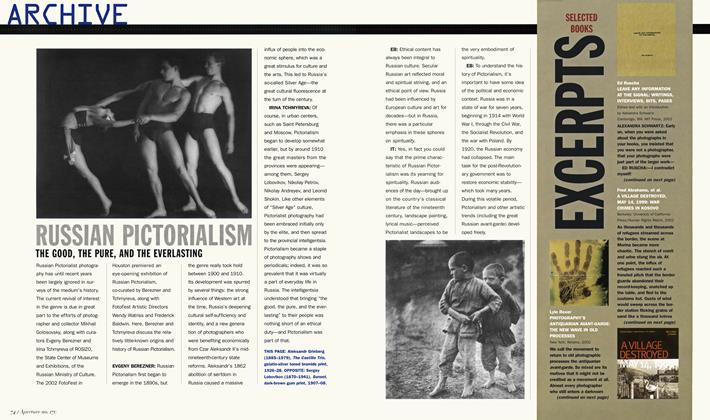

Archive

ArchiveRussian Pictorialism: The Good, The Pure, And The Everlasting

Spring 2003 By Evgeny Berezner -

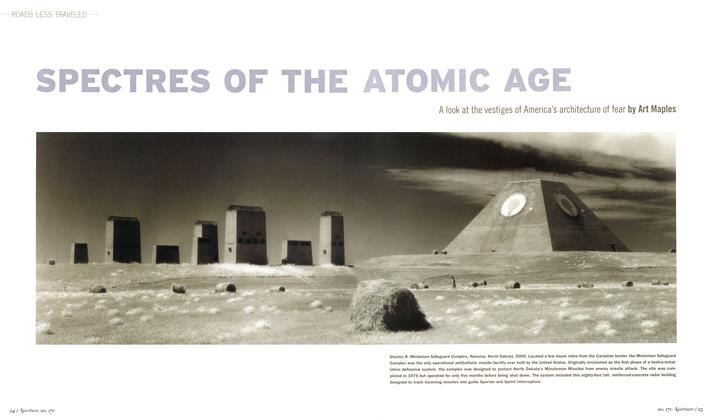

Roads Less Traveled

Roads Less TraveledSpectres Of The Atmoic Age: A Look At The Vestiges Of America's Architecture Of Fear

Spring 2003 By Art Maples

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Witness

-

Witness

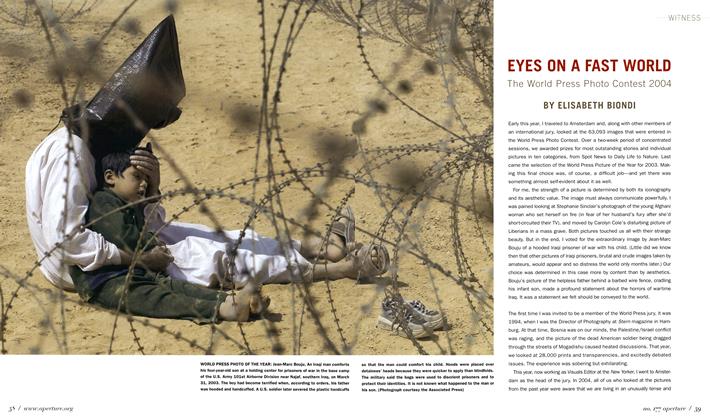

WitnessEyes On A Fast World The World Press Photo Contest 2004

Winter 2004 By Elisabeth Biondi -

Witness

WitnessMikhael Subotzky Inside South Africa's Prisons

Fall 2007 By Michael Godby -

Witness

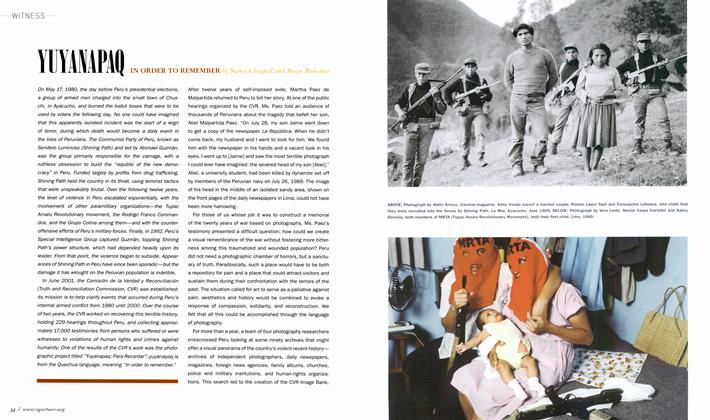

WitnessYuyanapaq

Summer 2006 By Nancy Chappell, Mayu Mohanna -

Witness

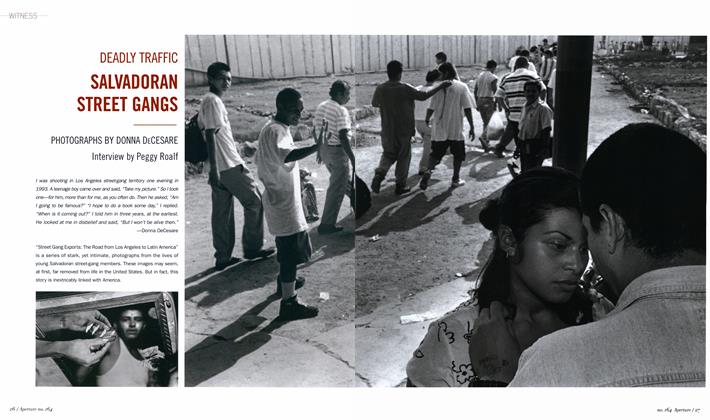

WitnessDeadly Traffic Salvadoran Street Gangs

Summer 2001 By Peggy Roalf -

Witness

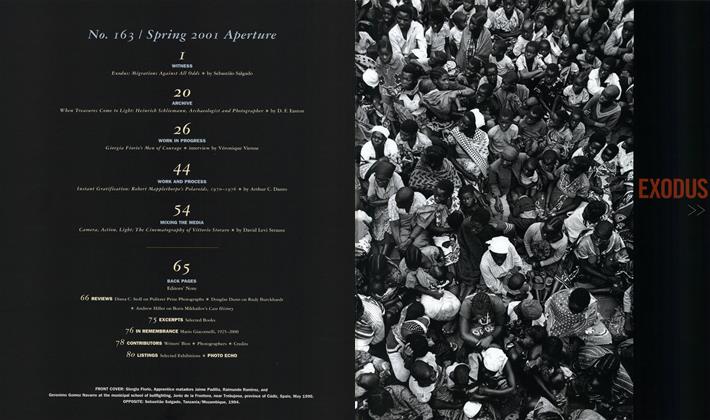

WitnessExodus Migrations Against All Odds

Spring 2001 By Sebastião Salgado -

Witness

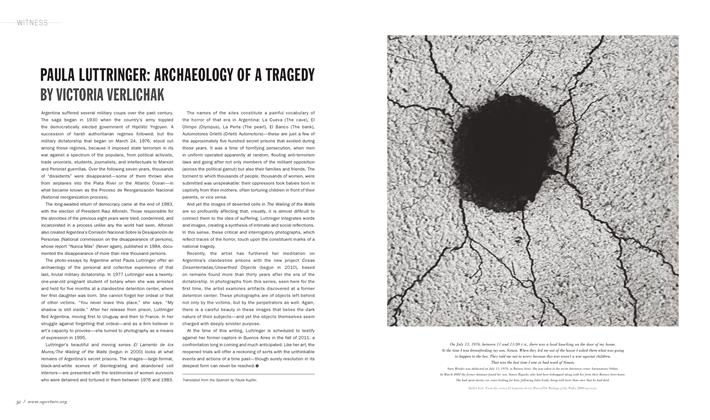

WitnessPaula Luttringer: Archaeology Of A Tragedy

Spring 2012 By Victoria Verlichak