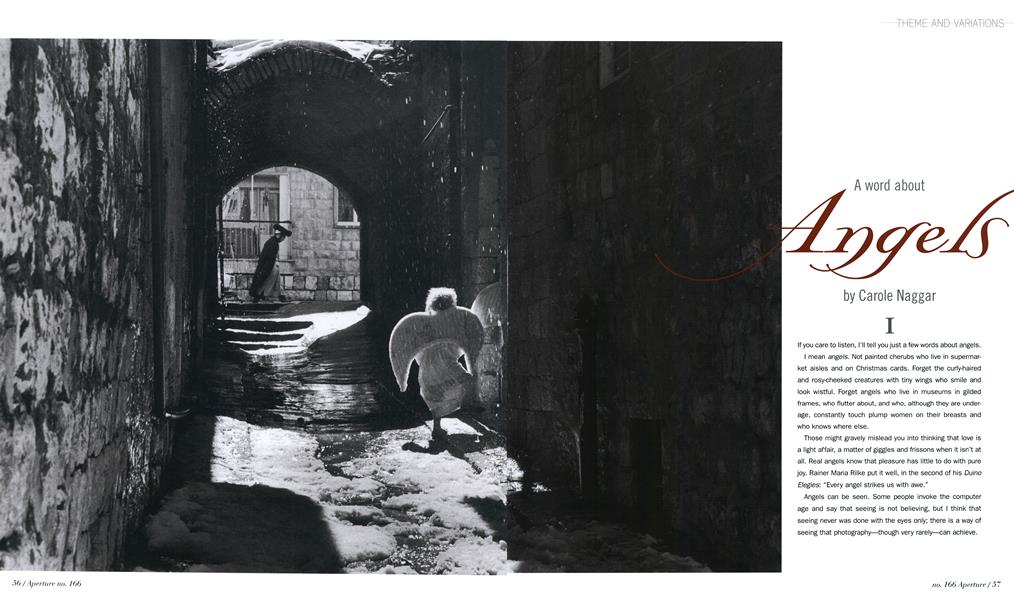

A word about Angels

THEME AND VARIATIONS

I

Carole Naggar

If you care to listen, I'll tell you just a few words about angels.

I mean angels. Not painted cherubs who live in supermarket aisles and on Christmas cards. Forget the curly-haired and rosy-cheeked creatures with tiny wings who smile and look wistful. Forget angels who live in museums in gilded frames, who flutter about, and who, although they are underage, constantly touch plump women on their breasts and who knows where else.

Those might gravely mislead you into thinking that love is a light affair, a matter of giggles and frissons when it isn’t at all. Real angels know that pleasure has little to do with pure joy. Rainer Maria Rilke put it well, in the second of his Duino Elegies: “Every angel strikes us with awe.”

Angels can be seen. Some people invoke the computer age and say that seeing is not believing, but I think that seeing never was done with the eyes only; there is a way of seeing that photography—though very rarely—can achieve.

It happens in these fleeting moments when appearances reflect some truth that is usually hidden. This truth is made manifest by a small gesture, the way a shadow redraws a face, the way a light both blinds and illuminates.

II

Not all appearances of angels, by any means, are recorded on film, but you will not always need an intercessor: you can see angels for yourself.

They may appear at dawn, when everyone is still asleep; or just before the darkest hour, when we let go of reason and surrender to our private ghosts. Then an angel may come, and his coming has to do with essential questions, those willingly forgotten in the hysterical bustle of the project-bound city where we live, because we are ambitious and want to be at the center of things. As it turns out we are wrong, because angels prefer peripheries to centers.

So then where do angels live?

Some lived in peace in medieval and baroque churches in the heart of Europe, like those angels photographed in Croatia by Keichi Tahara. Once in a small church not far from Zagreb an old priest told him that “only when sun and clouds mix do angels show their face.”

But now that Europe’s heart has been thrown to the dogs, the churches destroyed by bombings, where do these angels wander?

III

Nowadays they rarely have a home. They seem to have become yet another figure of dispossession and exile, maybe the faithful companions and guardians of the millions of refugees that have left their countries for the megalopolises of India or Indonesia, the suburbs of Mexico City, Jakarta, or Cairo.

And their name? Angels have no name, just as they have no place. Walter Benjamin, in the Talmudic tradition, thought that there was an angel for each man and woman, an angel who represented the person’s secret persona. The angel’s name, however, remained hidden. Then in the guise of each person’s angel or his secret name his celestial ego would be woven in the drape suspended in front of God’s throne.

Why do angels manifest themselves? And once they are on earth, where do they live? Benjamin’s angel, whose presence weaves together forces of angelic and demonic life, appears as the sign of a mystical transformation, an awakening to love’s cosmic force. “He inhabits those things I no longer own,” says Benjamin. “He makes them transparent: behind each appears the one to whom they are destined.”1

IV

Angels live within the discarded shells of our existence, within “things” to which we are no longer linked by ownership or usage. Once we have renounced owning them, there is room for the angel to inhabit them. Would that be why they like to appear away from the centers? Or would it be because silence is essential to their coming?

Silence, and a landscape reduced to essentials: far at sea, far from home, on the boat where Baudelaire and Coleridge's albatross staggered unto the deck, lost like the poet into the unknowing crowd. But angels are not lost: they come to our scrubbed decks with a purpose. Onto our shores, into the green grottoes where Ulysses’s companions heard the bewitching call, and thought that sirens were singing. All the way north on the shimmering ice, where hunters can make out their prey from afar because of the minuscule trembling aura of heat that the beast’s breath draws in the frozen air. Where the color white has three hundred names. In an island by the Baltic Sea where the ocean is a pale violet. To the west the sunset is bloody like a crime, and the only possible instrument the sliver of moon rising to the east, a heavenly scythe, and if it is day or night we do not know.

V

Angels may come in a desert, as manna, sugary white and light, sent to quench an everlasting thirst and hunger for love. The desert where a tribe has wandered or not, seeing burning bushes and columns of smoke that might be mirages, born from the extreme heat and their longing for the new land, or might not be; where Jacob met his angel, the one who broke his thigh with a sweep of his powerful wings. And yes, it was not fair play, but the angel did it anyway, for his own reasons.

In a place where you would know right away that the sky continues, the earth like the wings pursues the shoulder blades and spreads out with the three hundred names of white that is all the colors. Angels are especially fond of these places: maybe they are a little vain and know that this is where they look best, even though their faces habitually remain hidden. These are the places in history where their appearances have been recorded the most, by trusted witnesses that you may or may not believe.

But angels are not particular. And for that reason, though we are neither prophet nor tribe nor great philosopher, they might also come to us, in the cities of the world, even if we are not prepared: who is, ever?

VI

We will know because our flesh will crawl and our hair stand on end, even though it’s not the Angel of Death yet. We have a little time, time to love, time to read, maybe.

Rather, remember that though they are ministers of God, guardians, conductors of constellations, executors of laws, protectors of the chosen, angels will often come in pairs for company, wearing sneakers; they approach exchanging their many comments on the human race where they once belonged. They may come in the dreary public square dreamt by a famous architect, in a suburban mall, an underground parking lot. Invisible to most, but not to those who look hard.

They love to visit a pregnant woman. When a wing’s tip brushes her stomach she will feel inside a fluttering of wings unfolding. For an instant her whole body will expand and fly, touching the stars. She will know that she is both one and the other, and according to her disposition she will feel awe or pure joy or incredible sadness or all of these. This is the work of the angel.

For there is an instant when the shoulder’s thin blade does not end; it flows from the body, fulfilling Icarus and Theseus’s dreams of flight, and the body opens up.

VII

Why? Because the angel has delivered his message. For we have always thought that angels were messengers, and their Flebrew name (Mal’ach), as their Greek one {angelos), confirms it. “Then God,” says the Koran, “created wind, and gave it innumerable wings. He ordered him to carry the water; so he did. His throne was upon water, and water upon wind.” Like the winds, bearers of divine messages, the angels are intermediaries between earth and sky.

Do angels live a long time? We don’t think so. In the Talmudic tradition, the multitudes of angels that God ceaselessly creates and who ceaselessly sing His praises live only for a few seconds before disappearing, snuffed out like the spark on a piece of burning coal.

Which brings us back to photography, where angels appear, both evidence and enigma: we cannot believe that the angel is here yet cannot deny that we see him. Though he does not inhabit our time or space, he was caught and gleams (like the spark on a piece of burning coal).

Think of Joel-Peter Witkin whose many Satans reside in his Albuquerque studio, feathery at one end, hairy at the other, smirking, pondering skulls. For they are angels too though they make us look away then look again in fascination (as I imagine we shall when angels come).

VIII

Walter Benjamin describes the angel of history: a fierce wind is blowing into his wings, pushing him back as he contemplates the wreckage of our time. Benjamin’s angel was born of both his nostalgia and his desire for a better future. The first stirrings of what would be the Holocaust were making him and his angel weary, fragmented: they were right. Ultimately, the savage wind of history would break their wings like sticks—like Jacob’s thigh.

But to Rilke the angel remained both exhilarating and aweinspiring, the guardian of our spiritual future; the creature who already embodied the transformation of the visible into invisible that the poet sought to accomplish.

Photography may transform the invisible into visible. But at times, drawing with light and wind, it succeeds in doing just the opposite. And at times the angel will lend us a feather to dip into ink and write a text, even though we cannot hope to solve his essential mystery. ©

Note:

1 Walter Benjamin, Agesilaus Santander, 1933. Cited in Gershom Scholem, “Walter Benjamin und sein Engelm,” Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1983. The title Agesilaus Santander is an anagram of “Der Angelus Satanls,” also mentioned In many Flebrew texts such as the Midrasch Rabba on Exodus (20-10) and in the New Testament in the Epistle of Saint Paul to the Corinthians II, chapter 12:7.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

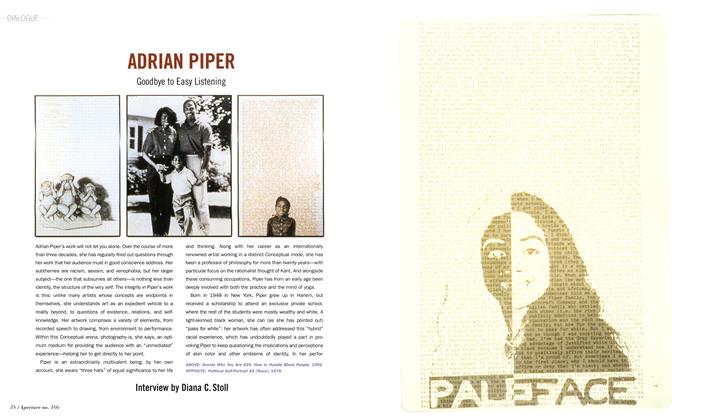

Dialogue

DialogueAdrian Piper

Spring 2002 By Diana C. Stoll -

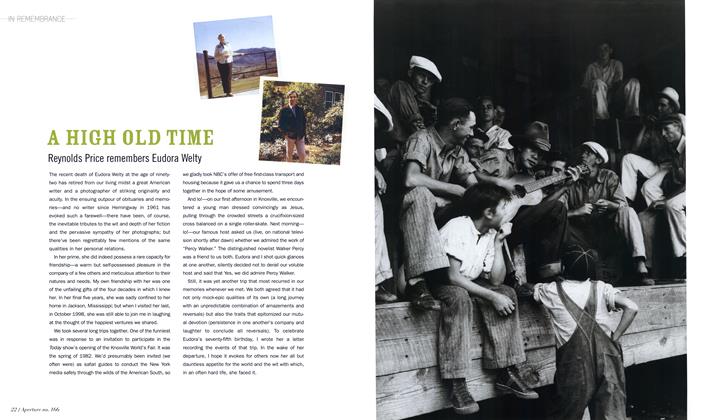

In Remembrance

In RemembranceA High Old Time

Spring 2002 -

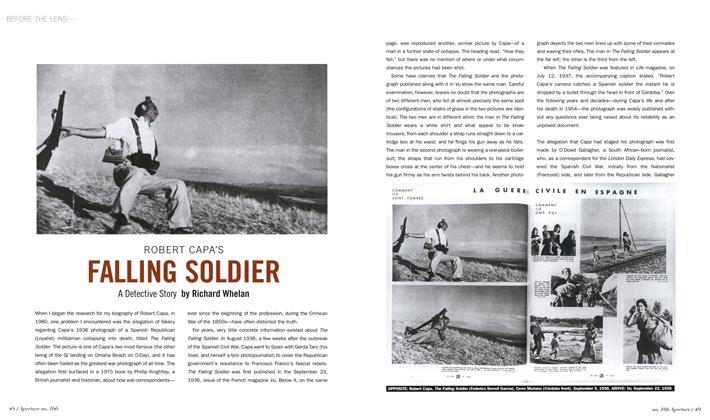

Before The Lens

Before The LensRobert Capa's Falling Soldier

Spring 2002 By Richard Whelan -

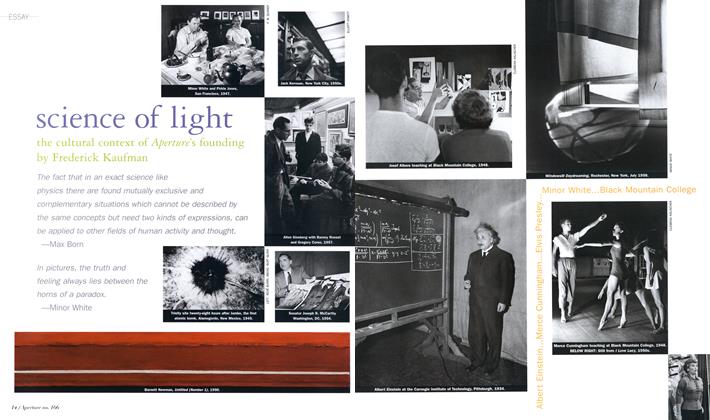

Essay

EssayScience Of Light

Spring 2002 By Frederick Kaufman -

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaNew Style Sacred Allegory The Video Art Of Shirin Neshat

Spring 2002 By Minna Proctor -

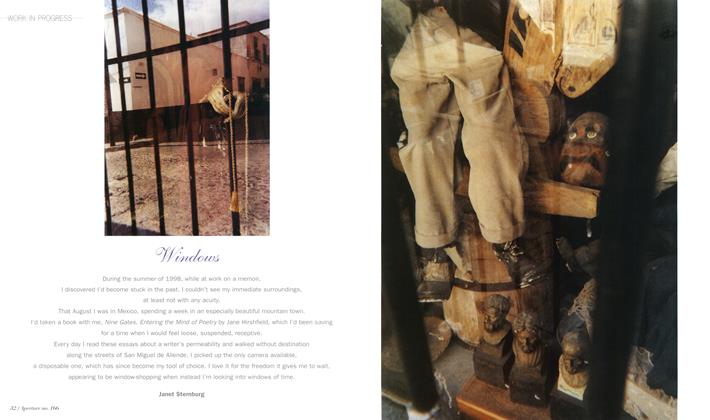

Work In Progress

Work In ProgressWindows

Spring 2002 By Janet Sternburg

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Carole Naggar

-

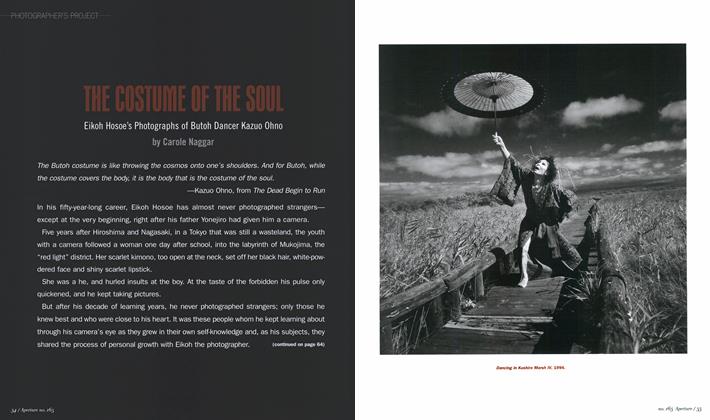

Photographer's Project

Photographer's ProjectThe Costume Of The Soul

Winter 2001 By Carole Naggar -

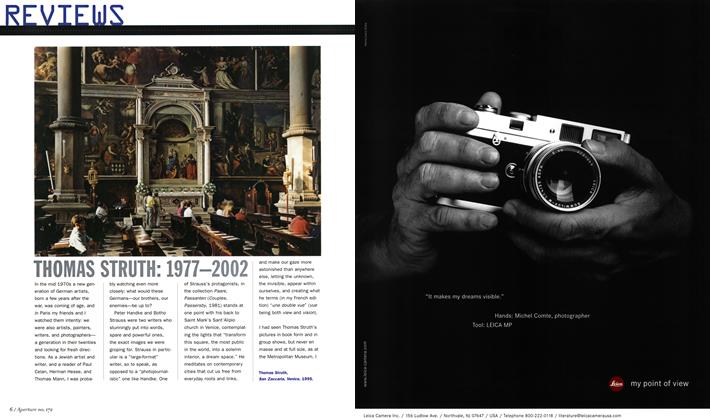

Reviews

ReviewsThomas Struth: 1977-2002

Fall 2003 By Carole Naggar -

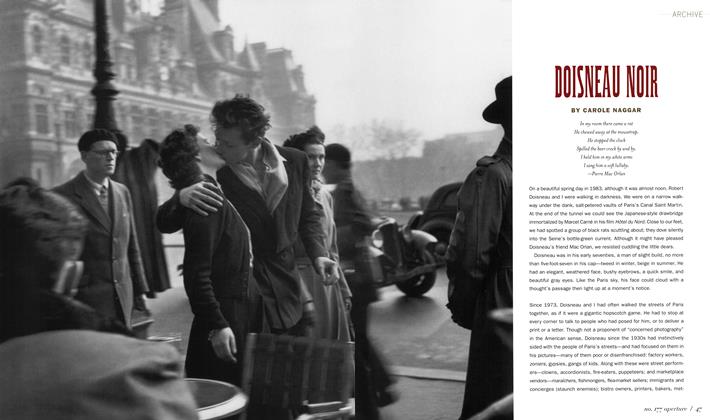

Archive

ArchiveDoisneau Noir

Winter 2004 By Carole Naggar -

Reviews

ReviewsI Need A Camera: The Films Of Raymond Depardon

Spring 2005 By Carole Naggar -

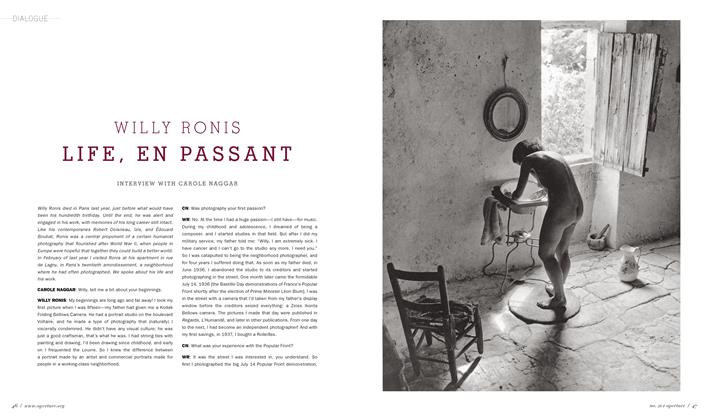

Dialogue

DialogueWilly Ronis Life, En Passant

Winter 2010 By Carole Naggar -

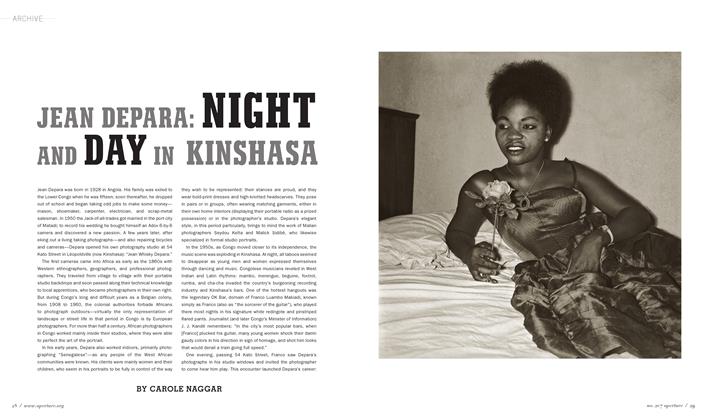

Archive

ArchiveJean Depara: Night And Day In Kinshasa

Summer 2012 By Carole Naggar

Theme And Variations

-

Theme And Variations

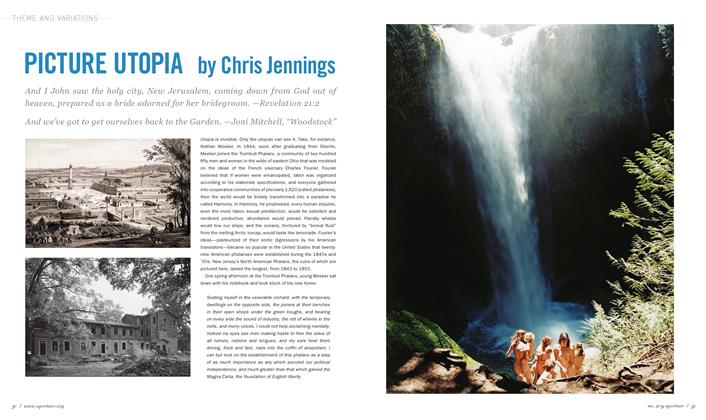

Theme And VariationsPicture Utopia

Winter 2012 By Chris Jennings -

Theme And Variations

Theme And VariationsA Calamity Of Heart

Fall 2010 By E. L. Doctorow -

Theme And Variations

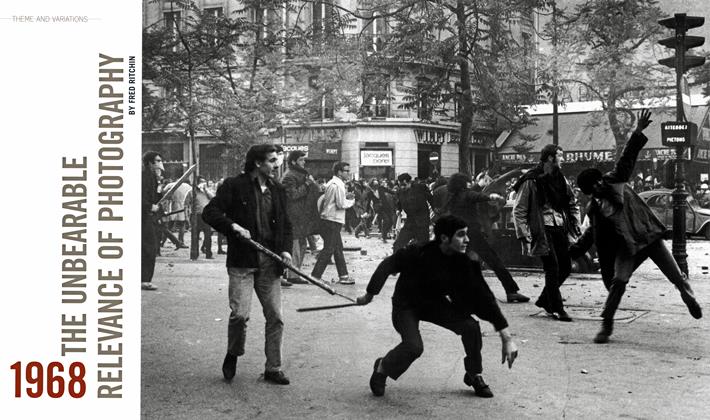

Theme And Variations1968 The Unbearable Relevance Of Photography

Summer 2003 By Fred Ritchin -

Theme And Variations

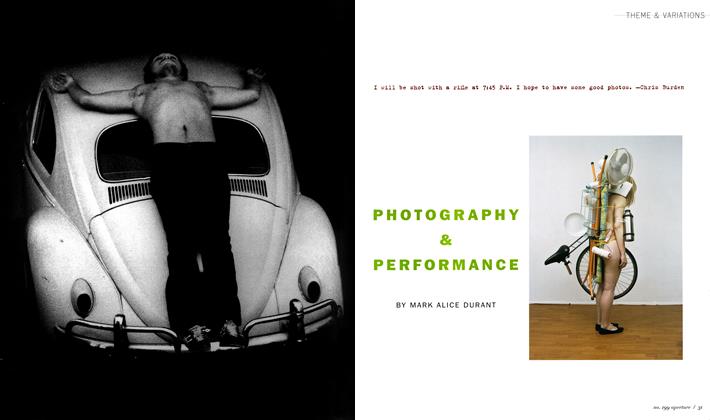

Theme And VariationsPhotography & Performance

Summer 2010 By Mark Alice Durant -

Theme And Variations

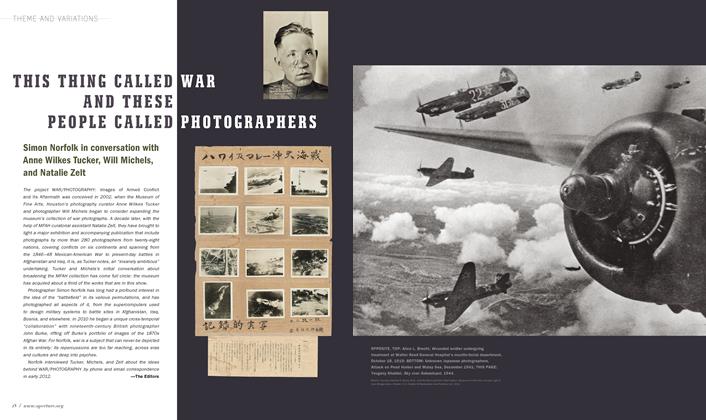

Theme And VariationsThis Thing Called War And These People Called Photographers

Fall 2012 By Simon Norfolk, The Editors -

Theme And Variations

Theme And VariationsVote Here

Winter 2007 By William Drenttel, Jessica Helfand