Flashback: The Photography of Dr. Harold Eugene Edgerton

Gus Kayafas

In 1965 I went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology [MIT] as a freshman. I arrived a little bit early and while wandering around, I found a gallery. Dr. Harold Edgerton, whom we called "Doc," was always proud of saying he had the only museum that was never closed. He had the two hallways where his laboratories and offices were lined with original photographs—not behind glass— with all kinds of explanations. He was very proud of the fact that they were never stolen but that they were always worn out, because people would rub and touch the print—"look at that shockwave!" and so on. Photography had been a hobby of mine. I signed up for his course, became his student, and gradually worked with him. Doc and I started printing together, and he and Minor White gave me a job working as a technical assistant at MIT. Then I went to Massachusetts College of Art on the Photography, Film and Video program. When I found out that Doc had paid my salary at MIT out of his own pocket I went to him and proposed that we do a portfolio. This happened in 1976 or '77. After we finished this portfolio we worked on a number of exhibits in art museums and galleries. We formed a partnership, and I began producing editions of his work and arranging many exhibitions. From 1980 until his death in 1990 we worked together often. As we printed the images he would tell me about them.

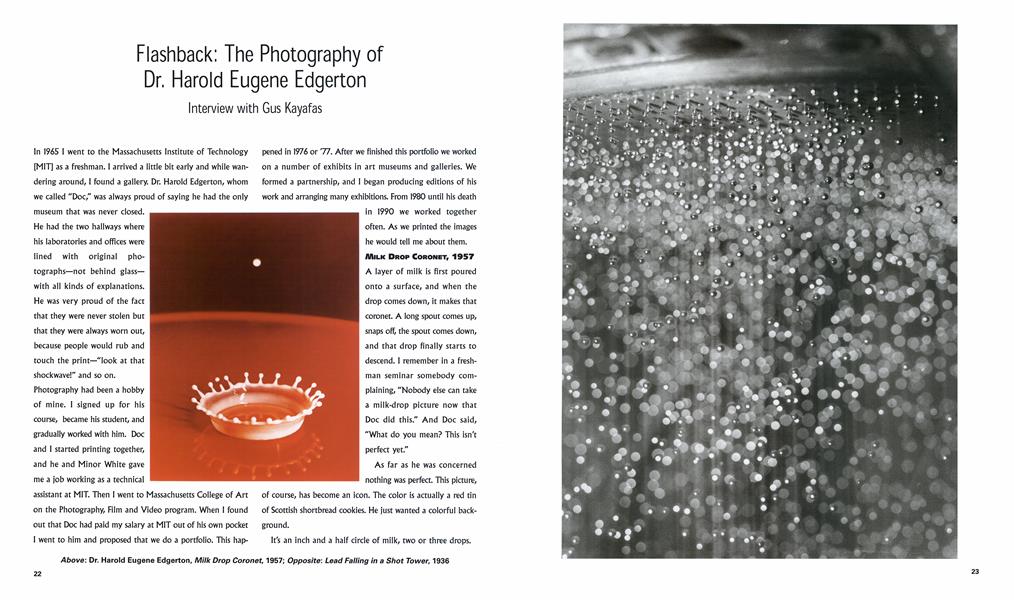

MILK DROP CORONET, 1957

A layer of milk is first poured onto a surface, and when the drop comes down, it makes that coronet. A long spout comes up, snaps off, the spout comes down, and that drop finally starts to descend. I remember in a fresh man seminar somebody com plaining, "Nobody else can take a milk-drop picture now that Doc did this." And Doc said, "What do you mean? This isn't perfect yet:'

As far as he was concerned nothing was perfect. This picture, of course, has become an icon. The color is actually a red tin of Scottish shortbread cookies. He just wanted a colorful background.

It's an inch and a half circle of milk, two or three drops.

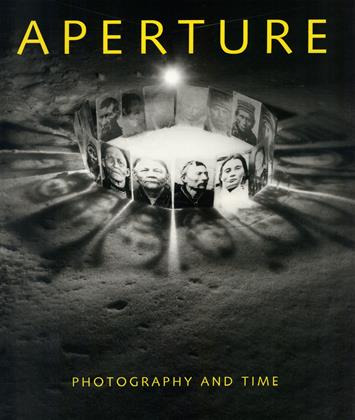

LEAD FALLING IN A SHOT TOWER, 1936

This image was made in a tower for making shotgun shot. That's liquid lead dripping through dies, dropping a hundred feet. As it drops, the lead is formed into a sphere like a rain drop and it solidifies. Doc really loved this picture. He thought this was an arty picture because it was so abstract. There are some prints in which he would crop out of it. In these images there is no way you could tell what the original subject was.

PIGEON RELEASE, 1965

This was shot initially with a 4-by-5 color negative. One of the earlier pictures of a pigeon in flight became known as Rising Dove. Doc called it Pigeon Release; but some museum curator called it Rising Dove—Doc always made jokes about museum curators calling pigeons doves. The earlier version was one of the first pictures the Museum of Modern Art acquired when Stephen was there. About two years later there was a Harper's Bazaar that featured this photograph with a child's face in the background looking up, montaged, and it was signed "Steichen." Doc called him up and said, "What the hell are you doing?" And Steichen apologized, "I didn't think you'd mind." And Doc said, "Of course I mind, you took my picture, you put another one in it, and you put your name on it. That's not right!"

And from that day they became fast and good friends.

MILK DROP SPLASH SERIES, CA. 1935

This was from a high-speed movie camera that Doc invented, which shot 35mm movie film and synchronized with a flash. Instead of stopping and starting, which is what most movie film does, the film just moved through evenly, and as it reached a certain position, the flash fired. The next time it reached that position the flash fired again. So long as the flash was able to recycle fast enough to give you a full charge you could make these photographs of remarkable phenomena. When I found the film I was so excited that there was some footage from which I could make photographs.

This is a series of six exposures. If you look carefully, right at the edge of where the sphere hits the surface of milk you see the reflections, but you also see these little waves starting to form [l]. You'll notice it has serrated crenellations almost like a castle—those evolve into the drops, into the crown. Now you begin to see the crown start to push up [2]. As that drop has hit, all of the energy that was going down has now pushed out. As it pushes out it pushes against the fluid that's already there so a wall of milk arises. Now you begin to see the crown shape [3]. The other thing that's really interesting is that you see the direction of the flash, because of the shadow. Now we have a complete crown, a shadow of the crown, a reflection of the crown, and this surface in the background. If you look at the top edge, you see it has stayed the same through it all [4]. In the next frame the crown has begun to come back down and move back in. You see these concentric rings and these wonderful smaller little spikes [5]. In the final image the surface has been completely changed. It has impacted and spread out so we actually had to move the frame slightly when we made the print [6].

I remember Doc was interviewed for a TV program and he said, Tm not an artist, I'm a scientist." Afterwards I said, "Of course you're an artist, how many milk-drop pictures have you made?" He said, "Hundreds." I said, "Thousands, I've counted them. Why did you pick the two or three you published?" He said, "Well, those are the beautiful ones." And I said, "Well, that's what art is about; it's not just strategies and concepts, it's about finding that perfect tension between describing something and making it visible, and somehow still allowing it to be mysterious or beautiful."

BULLET THROUGH PLEXIGLAS, 1962

This is a photogram, a cameraless picture. It's a 30-calibre bullet and you'll notice these black spots at the top right; these are where the bits of Plexiglas actually punched a hole in the film. It was a sheet of 8-by-lO high-contrast film. It's a pointsource flash, so just as you get sharp shadows cast by the point source of the sun, this would cast very sharp shadows. In America, often when you're driving, you'll see a heat differentiation coming off the asphalt and it looks like a mirage, like water because that's the way our brains read it. The light is being bent by that change in the density of the air from the heat, and that's what's happening here. The change in pressure creates the shockwave, and the light actually gets bent, so it ends up not exposing the film evenly. There's a secondary wave of shockwaves, and that's the one that hits the microphone to set the flash off. There is a piece of Plexiglas, in a vise with a microphone, with a bullet going through it. Essentially, instead of a photogram made like a contact print—because this is a point source light—the film is about ten or twelve inches away from what happens. This is something Doc developed during World War II to study projectiles and how they worked. This led to his interest in the speed of sound in different media.

ANTIQUE GUN FIRING, 1936

This is a late 1800s Colt revolver that a graduate student had. The microphone [bottom of picture] is a really early one. What you see is how much smoke comes out of a gun. It's just all over the place. All of these streaky things here are pieces of glowing embers shooting out of it.

STONEHENGE AT NIGHT, 1944

Doc was always interested in a visual display that would make people think about amazing things in terms of tirrje, either really short or really long. Probably his favorite place on earth next to MIT was Stonehenge, because he looked at it as the oldest computer. He photographed Stonehenge from wartime on—he made some amazing pictures. He used it as a test site for his airplane flash, which was used to determine where the D-Day invasion was actually going to happen. There were three potential sites for it and they were doing night photography to make sure there was no troop movement. That's how they confirmed Normandy as the location. He got a rnedal of honor for that.

Martin Barnes

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

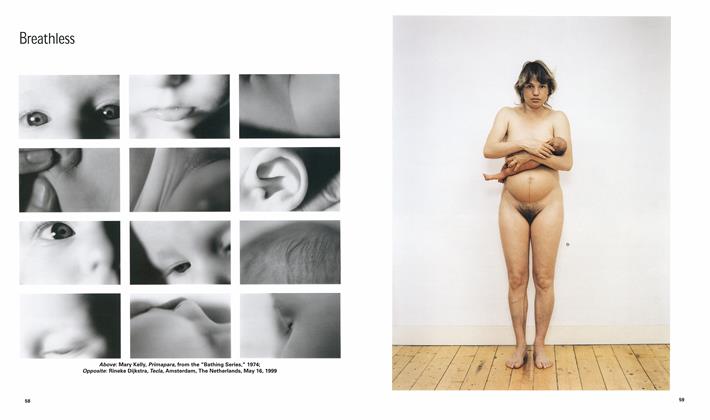

Breathless

Winter 2000 By Martin Barnes, M H-B -

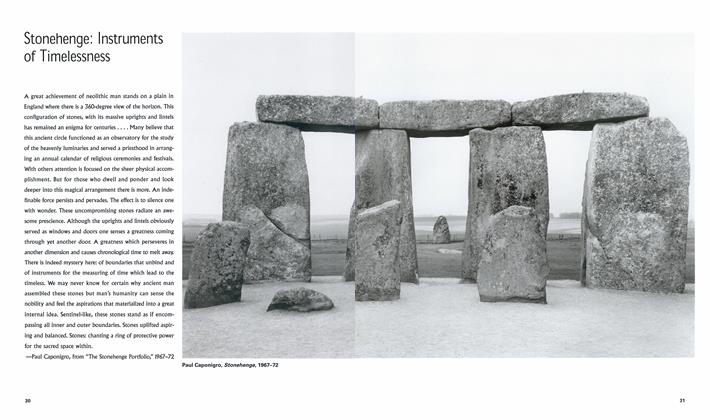

Stonehenge: Instruments Of Timelessness

Winter 2000 By Paul Caponigro -

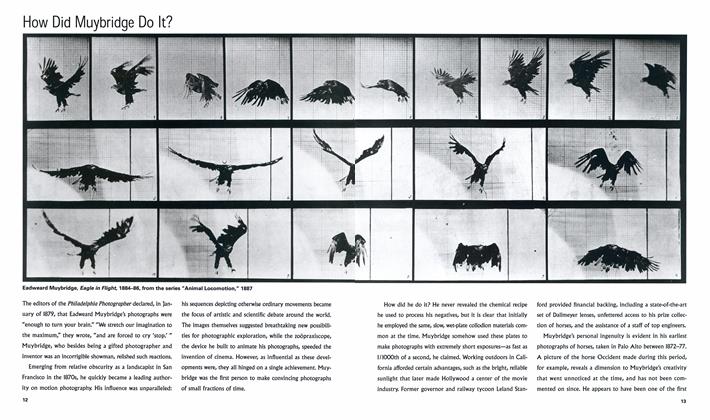

How Did Muybridge Do It?

Winter 2000 By Phillip Prodger -

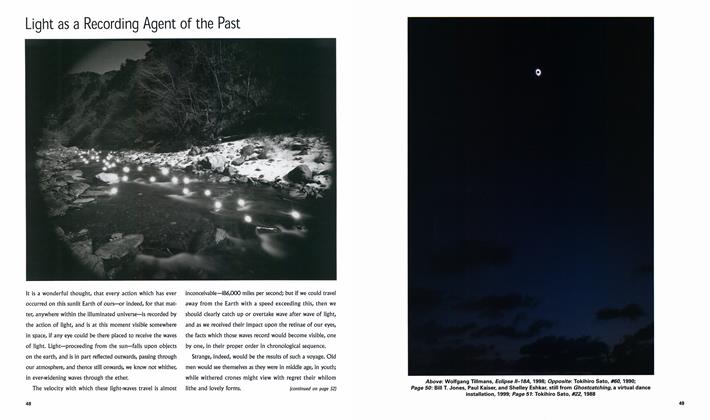

Light As A Recording Agent Of The Past

Winter 2000 By W. Jerome Harrison -

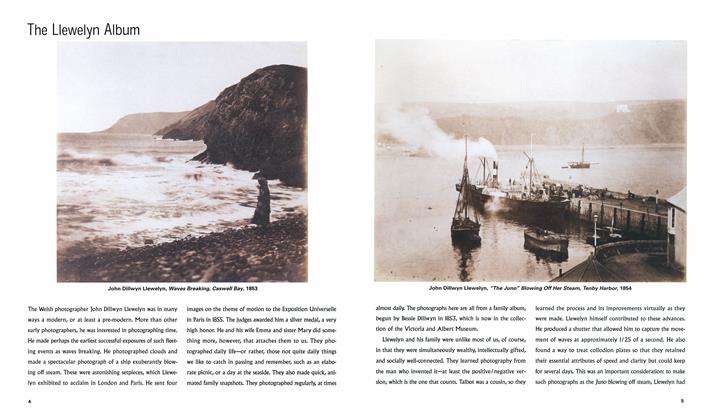

The Llewelyn Album

Winter 2000 By M H-B -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasMariko Mori, Empty Dream Brooklyn Museum Of Art: April 8-August 15, 1999

Winter 2000 By Lesley A. Martin