RROSE IS A RROSE IS A RROSE

PEOPLE AND IDEAS

Lisa Liebmann

"RROSE IS A RROSE IS A RROSE: Gender Performance in Photography," opened at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, January 17, 1997, traveling to the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, August 17—November 30, 1997.

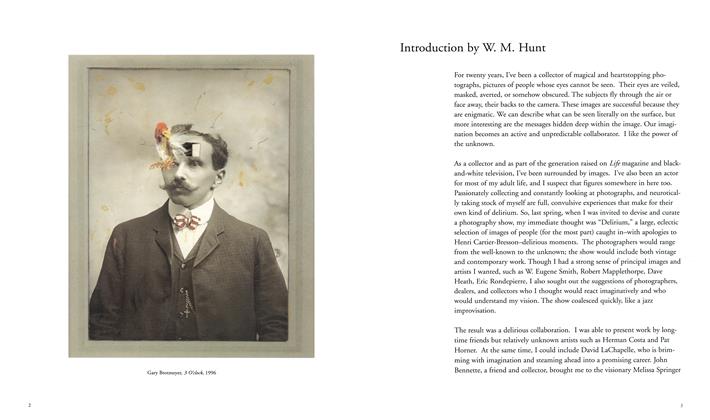

It's happened, folks: Everything interesting is academic. With few remaining frontiers to explore or unstudied peoples to examine, ethnography has evidently turned inward, here in the West, and researches into our own sexual mores and so-called gender practices have become the preeminent symptom of the day, effecting great changes in everything from corporate ecology and military life to graduate seminars in the history of art. Outlaw visions of identity and sex have entered the mainstream and stormed the ivory tower. Some of this is no doubt for the good. But unfortunately, some of the juiciest themes of the underground past— transvestism perhaps chief among them— have in the process been reduced and overexposed and are rapidly drying up even as they continue to saturate “the culture.”

Against this quizzical, rather perilous backdrop “Rrose is A Rrose is A Rrose”—pronounced Eroz is Eroz is Eroz— gingerly assumed its poised position, meaning neither to bore nor to titillate. Subtitled “Gender Performance in Photography,” the show set about to trace a concise, vivacious, and on the whole rather clean history of complicitous role-playing in twentieth' century portrait photography, putting its well-placed emphases on Europe between world wars and on the recent past. The exhibition, curated by Jennifer Blessing, was on view in the Robert Mapplethorpe galleries, appropriately enough, of the uptown Guggenheim Museum and comprised eighty photographs by twenty-four artists including Mapplethorpe along with such historically diverse practitioners as Man Ray and Cindy Sherman. It was divided into contiguous but discrete prewar and postwar sections that could be entered from either direction.

What the exhibition lacked in heft it made up for with lightness. The fey Duchampian spirit, embodied in Man Ray’s famous photo-portrait of Marcel Duchamp as Rrose Sélavy, 1920—21, presided over both periods, and an exalted artifice seemed to characterize all of the exhibition’s high points.

Presented together like a crop of debutantes on a long, curved wall were no fewer than eight virtuosically composed portraits of esthetes, artists, and aristocrats of the ’20s and ’30s, taken by the underestimated Cecil Beaton. Beaton’s pursuits of sexual adventure and social advancement are transmogrified by muse and lens into depictions of a rarefied, seductive world governed by such imperturbable deities as the lovely young Countess Castega, 1927, in mannish dress, and an equally lovely, mannish Gary Cooper, 1931, in swashbuckling costume, posing in majestic indolence in the sun on a studio lot.

Then there was the surprising Madame Yevonde. For starters she was British: Yevonde—her given first name— name—attended school in Belgium and studied at the Sorbonne but spent the rest of her busy days in London where, in addition to her duties as an ardent suffragette, doting wife, and energetic photography lecturer, she portrayed ‘30s society belles extravagantly rigged out as mythological goddesses. Something stark and transfixed cuts through the frippery in these pictures. One is reminded at once of fancy-dress portraits of the eighteenth century and of contemporary transvestite work, for instance by the photographer David Seidner, in whose commissioned costumed portraits we find a similar union of frivolity and classical rigor. La Yevonde was also an experimenter with color; and her frothy, faintly lurid Vivex color-process tones would be right on pitch in any current fashion magazine.

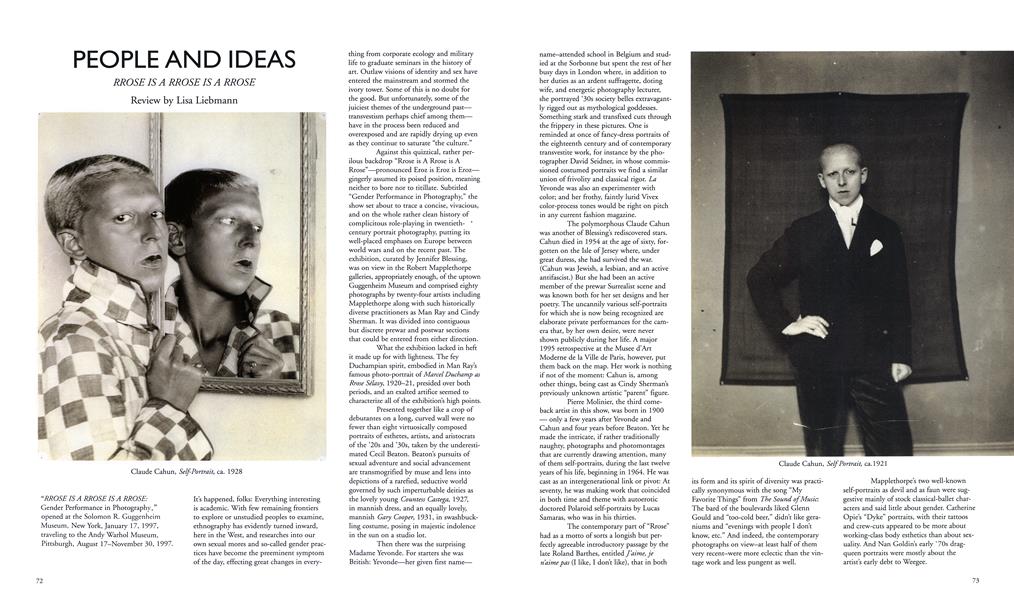

The polymorphous Claude Cahun was another of Blessing’s rediscovered stars. Cahun died in 1954 at the age of sixty, forgotten on the Isle of Jersey where, under great duress, she had survived the war. (Cahun was Jewish, a lesbian, and an active antifascist.) But she had been an active member of the prewar Surrealist scene and was known both for her set designs and her poetry. The uncannily various self-portraits for which she is now being recognized are elaborate private performances for the camera that, by her own desire, were never shown publicly during her life. A major 1995 retrospective at the Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, however, put them back on the map. Her work is nothing if not of the moment: Cahun is, among other things, being cast as Cindy Sherman’s previously unknown artistic “parent” figure.

Pierre Molinier, the third comeback artist in this show, was born in 1900 — only a few years after Yevonde and Cahun and four years before Beaton. Yet he made the intricate, if rather traditionally naughty, photographs and photomontages that are currently drawing attention, many of them self-portraits, during the last twelve years of his life, beginning in 1964. He was cast as an intergenerational link or pivot: At seventy, he was making work that coincided in both time and theme with autoerotic doctored Polaroid self-portraits by Lucas Samaras, who was in his thirties.

The contemporary part of “Rrose” had as a motto of sorts a longish but perfectly agreeable introductory passage by the late Roland Barthes, entitled J’aime, je naime pas (I like, I don’t like), that in both its form and its spirit of diversity was practically synonymous with the song “My Favorite Things” from The Sound of Music. The bard of the boulevards liked Glenn Gould and “too-cold beer,” didn’t like geraniums and “evenings with people I don’t know, etc.” And indeed, the contemporary photographs on view—at least half of them very recent—were more eclectic than the vintage work and less pungent as well.

Mapplethorpe’s two well-known self-portraits as devil and as faun were suggestive mainly of stock classical-ballet characters and said little about gender. Catherine Opie’s “Dyke” portraits, with their tattoos and crew-cuts appeared to be more about working-class body esthetics than about sexuality. And Nan Goldin’s early '70s dragqueen portraits were mostly about the artist’s early debt to Weegee.

Here, especially, the triumph of extreme artifice over relative naturalism seemed complete. All vérité styles—from Brassais in the prewar section to Goldins in the new—looked wan or overfamiliar, even as hyperstylization and camp somehow looked fresh. (The bitsy whimsy, however, of Hannah Hoch’s collages and of Annette Messagers tiny dangling pictures of altered faces fell a bit flat.) Most to the point among the older generation of contemporary artists were the Polaroid pair, Samaras’s work and Andy Warhol’s series of self-portraits as an Elaine Stritch-style lady who lunches (on dry martinis), which was full of subtle emotion despite its lighter-than-light touch.

The most pizzazz among the younger generation was found in Matthew Barney’s electric-Easter color portraits of himself as a vaudeville satyr of the future (i.e. today’s young man); Christian Marclay’s erotic sewn-together LP album covers, which make sex between idols possible; Janine Antoni’s affectionately complicitous portrait-triptych of her mother and father in serially mutating roles (all configurations except mother-as-mother with father-asfather); and Lyle Ashton Harris’s solemnly wacky, formal studio-genre portraits of himself and various partners posed as AfricanAmerican royalty in fetchingly nuanced drag. These artists seem to be onto something new, perhaps a new Symbolist genre of bildungsroman in pictures.

But if it’s the dirt you want, don’t miss the cataloge. Assembled by the industrious Blessing to accompany the show, this energetic, eye-opening book—a zany confluence of gender weirdness and haute academe— is a semiautonomous organ and, to my view, the exhibition’s better as well as most enduring half. It is not entirely free of academic gibbering, but scanning through a few of the essays for good parts is definitely worthwhile. Artists from different periods who aren’t in the show, some well-known and others not, are most strikingly reproduced in the catalog: Urs Luthi’s self-portrait as male ingenue on the edge; Della Grace’s classically idealized homoerotic portraits of all the sexes; and the scabrous Chapman brothers, Dinos and Jake, with their high-resolution statues of Breughelesque mutants, such as a pair of penis-nosed Siamese twins with mouths like rectums, are just a few of works featured. Some artists in the show are in the catalog, seen in the light of a different age; I had forgotten about Beaton’s swinging London pictures from the ‘60s, such as a dressing-room portrait of Mick Jagger during his Performance days. Others are presented more revealingly; such as Lyle Ashton Harris’s Drag Racing, a diaristic project that is part personal and part advertising campaign, on the theme of black sheand he-male imagery, pornographic and merely fashionable, that also suggests some sort of fixation on Jeffrey Dahmer.

But the essays, by Blessing and four invited colleagues, steal the show. One after another, they flow through the catalogue, now almost merging right into one another, now letting pert little chapter headings break them up. Blessing’s is perhaps the most intelligent and encompassing. But the most adventurous and arresting prose belongs to Judith Halberstam, an associate professor of literature at the University of California, San

Diego, whose essay on “gender policing and gender performances in public spaces,” in particular rest-room rituals, was inspired in part by the frequency with which she “and others I know are mistaken for men in public bathrooms.” “From drag kings to spies with gadgets,” she rightly concludes, “gender and sexuality and their technologies are already excessively strange. It is simply a matter of keeping them that way.”

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

People And Ideas

-

People And Ideas

People And IdeasA Symbiotic Relationship: Collecting And The History Of Italian Photography

Summer 1993 By Carlo Bertelli -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasDictatorship Of Virtue: Multiculturalism And The Battle For America’s Future, Richard Bernstein

Winter 1995 By Elizabeth Fox-Genovese -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasSouthern Photo Art: Pushing The Boundaries

Summer 1989 By Glenn Harper -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasObscure Objects Of Desire: The Films Of Pedro Almodovar

Fall 1990 By Katherine Dieckmann -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasLetter From London

Fall 1983 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasAlfred Stieglitz: A Biography, Richard Whelan

Summer 1996 By Robert Adams

People And Ideas

-

People And Ideas

People And IdeasA Symbiotic Relationship: Collecting And The History Of Italian Photography

Summer 1993 By Carlo Bertelli -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasDictatorship Of Virtue: Multiculturalism And The Battle For America’s Future, Richard Bernstein

Winter 1995 By Elizabeth Fox-Genovese -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasSouthern Photo Art: Pushing The Boundaries

Summer 1989 By Glenn Harper