People And Ideas

William S. Burroughs At The Los Angeles County Museum Of Art: Pariah Or Pope?

Winter 1997 Frederick KaufmanWilliam S. Burroughs At The Los Angeles County Museum Of Art: Pariah Or Pope? Frederick Kaufman Winter 1997

WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS AT THE LOS ANGELES COUNTY MUSEUM OF ART: PARIAH OR POPE?

Frederick Kaufman

"Ports of Entry" traveling exhibition, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, Summer 1996

In terms of the gallery space allotted to "Ports of Entry: William S. Burroughs and the Arts," this exhibit is modest. In terms of mental space, I have rarely seen a more ambitious show. These five rooms are overwhelming. If anything, this exhibit is too exhaustive. Thus does “Ports of Entry” earn the dubious distinction of proving that curatorial triumphs do not necessarily translate into transcendent museum going.

Robert Sobieszek, the museum’s curator of photography, deserves tremendous kudos for bringing together these first editions of the novels, this wide-ranging selection of films and audiotapes, the numerous paintings, photographs, sculptures, mixed media, pictographs, and hieroglyphs. Sobieszek even went so far as to track down a bona fide Brion Gysin Dreamachine—a perforated spinning cylinder that supposedly stimulates mental imagery.

Gysin, the Swiss-born surrealist who deeply influenced Burroughs’s development as a visual artist, created this device with the misapprehension that it would make him millions. To put it bluntly, he was wrong. Here it is a somewhat forlorn presence, with its tinny Joujouka sound track and earnest warning to epileptics.

This exhibit showcases a number of different Burroughs: The writer, the painter, the photographer, the pseudoscientist, the muse. But all arguments regarding the genre to which the art of Burroughs properly belongs miss the point. Burroughs is, above all, a conjurer, a magician, an occultist intent on breaking the sacred vessels of normative perception. Even at his most unsavory and downright ugliest, there’s a redemptive effort behind every sublimation of his conscience, an effort to undo the cultural spell with which we’ve all been hypnotized. Burroughs is a postmodern Merlin, the possessor of a frightening power to quash quotidian taxonomies, and to coopt all aesthetic genres for his own, apocalyptic ends.

The sign posted outside “Ports of Entry” bears the following sinister warning: “Viewer and parental discretion is advised.” Indeed, this is a powerful and disturbing show. Burroughs sought to transform images into nonnarrative visual mantras, mystical glyphs as a violent antidote to technocratic tyranny. And there is a real edginess to much of the work, from the stark photomontage William Vacates Rooms to the haunting painted palimpsest of Lor the Angel of Death Spread His Wings.

The images from his early scrapbooks retain a mysterious, hieratic power. And those homunculi that haunt the late work, such as 1992’s Alien Penetration, are horrifying yet sinuously beautiful, evidence to the fact that Burroughs’s art has neither deteriorated nor retreated in its maturity.

Here are his shotgun paintings, violent and visionary, psychedelic and primitive. Here is Burroughs’s voice, his icy, deadpan descriptions of violent orgasm and terminal drug psychosis. Here are his homoerotic underminings of Time magazine, his homemade Rorschach inkblots with their visceral, hellish buzz of imminent danger—and then there is that Herb Ritts portrait, made expressly for The Gap.

The presence of a Gap ad in a Burroughs exhibit should give us pause, as should the merchandising effort which includes not only the standard poster and catalog, but a T-shirt, a video, an assortment of postcards, a Burroughs paper-clip box, pencils stamped with Burroughs quotes, and something called Poetry Slam: The Magnetic Word Game—for 2 to 4 players, ages 8 to adult.

All this is somewhat distasteful, but the commercial deployment of Burroughs into popular culture is not an issue because of some arbitrary insistence on rigid distinctions between high and low art; it is an issue because of the responsibility of a museum to present an authentic portrayal of an artist. One of the profound cultural legacies of Burroughs is his own particular brand of cosmic paranoia, a paranoia particularly obsessed with all manner of commodification. To commodify Burroughs is, on this basic level, to strip him of his meaning.

If Burroughs can be bought and sold on a mass level, he himself has become a part of what he has on numerous occasions called the “image sickness,” that virus he has gone to such great lengths to deplore in all manner of media. This is not to put on blinders and deny Burroughs’s own complicity in the broadbased process that has transformed him into what Gus Van Sant calls “The Elvis of Letters.” Yet, if art can be no more than a nuanced advertisement for the self, how can Burroughs ever transcend his popular identity as a wisecracking, blackhatted, counterculture boilerplate?

Clearly, the people at LACMA believe that Burroughs is something more than that guy in the black suit in those Nike ads. Of course, the articulation of this something takes effort. But Sobieszek doesn’t even give it a college try, and his pedantic catalog does nothing to address this glaring irony.

Here, Sobieszek’s grandiose prose traces Burroughs’s influence not only to the likes of John Giorno and Laurie Anderson but also to the graphic layout of Wired magazine, the video game “Mortal Kombat,” and Bill Gates’s software interface Windows 95. Sobieszek is not content to call Burroughs a pioneer. He must also be an astronaut, a freedom fighter, a satirist on a par with Jonathan Swift. He is Coleridge’s mariner, Twain’s Huck Linn, Castenada’s Don Juan. He is Hieronymous Bosch, the Marquis de Sade, David Bowie, Michel Loucault, and Ralph Waldo Emerson all rolled into one.

And then there is that pretentious indexed listing of cultural studies resources in the back of the book, implying that in order to really understand Burroughs one must also have mastered Barthes’s Elements of Semiology, not to mention Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. This miasma of reference comes off as nothing more than sycophantic aggrandizement.

A far more serious problem is that Robert Sobieszek, for all his obsessive didacticism, has not organized this show as well as he might have. Robert Mapplethorpe’s beatific portrait is lessened by being placed above a selection of Burroughs album covers. David Wojnarowicz’s haunting Bill Burroughs’ Recurring Dream could have benefited from a curatorial presence to help explicate the Mayan codex and centipede imagery. Yet all of a sudden, Sobieszek is nowhere to be found.

By the end, the show, like an addict’s body, has overdosed on its own rush of artistic influence. Its veins have clogged, its eyes lost their focus. The fact of influence—not its explanation—has been sufficient for Sobieszek. The result is an exhibit with impressive horizontal range, but absolutely no depth.

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Frederick Kaufman

-

Pictures

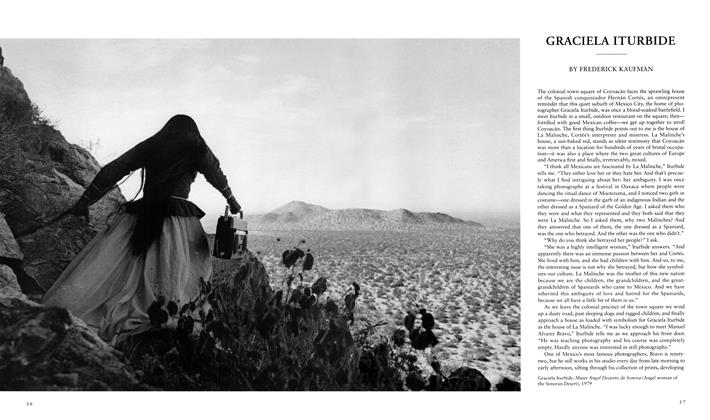

PicturesGraciela Iturbide

Winter 1995 By Frederick Kaufman -

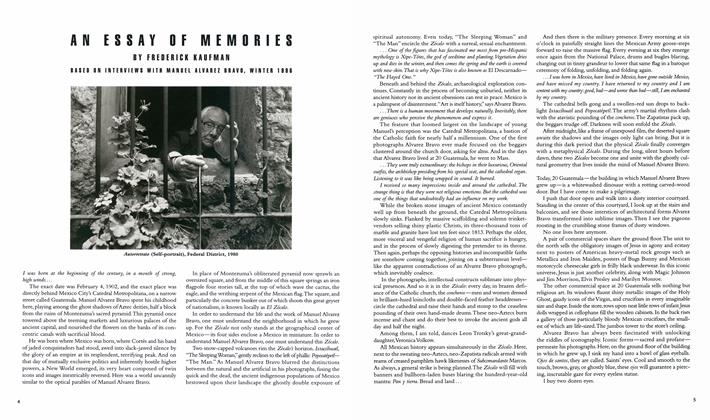

An Essay Of Memories

Spring 1997 By Frederick Kaufman -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasParanoia And The Postmodern Picaresque Review: "Spanish Cinema Now!" At Lincoln Center, New York City, December 1998

Spring 1999 By Frederick Kaufman -

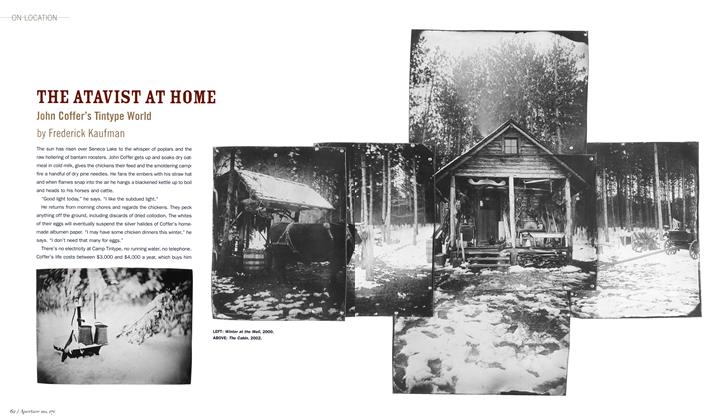

On Location

On LocationThe Atavist At Home: John Coffer's Tinytpe World

Spring 2003 By Frederick Kaufman -

Film

FilmOur Daily Bread

Fall 2007 By Frederick Kaufman -

Reviews

ReviewsBeaumont’s Kitchen

Spring 2010 By Frederick Kaufman

People And Ideas

-

People And Ideas

People And IdeasColor

Winter 1976 -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasBrassaï, 1899-1984

Winter 1984 -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasLooking At Lange

Spring 1978 By Anita V. Mozley -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasParticulars: From The Miller-Plummer Collection

Spring 1984 By Ann Jarmusch -

People And Ideas

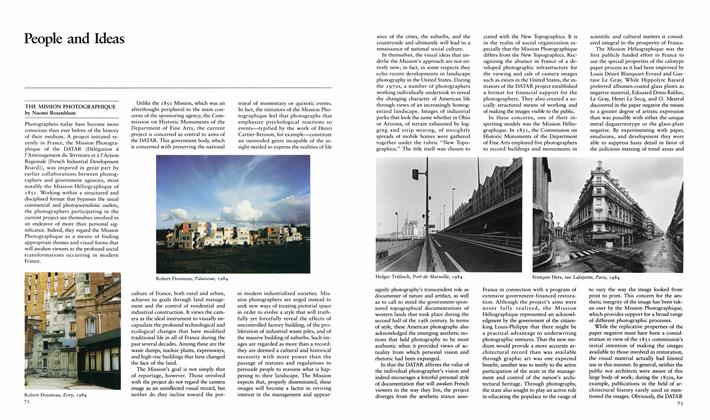

People And IdeasThe Mission Photographique

Winter 1985 By Naomi Rosenblum -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasThe Final Frontier?

Winter 1993 By Richard B. Woodward