JAPAN’S BEST-KEPT SECRET

Peter C. Jones

The prevailing Western view that nineteenth-century Japanese photography was produced largely for Western consumption has been challenged by Charles Schwartz, an American photography dealer and collector who has recently amassed a large collection of Japanese ambrotype portraits. Schwartz, who has specialized in nineteenth-century works for twenty years, maintains that these photographs, made by Japanese photographers exclusively for a Japanese clientele, may represent a significant aspect of early Japanese photography that has been overlooked by experts on both sides of the Pacific.

The existence of Japanese ambrotypes (glass collodion negatives mounted on a dark background to produce a positive image) is hardly news. Authors of books about early Japanese photography have routinely illustrated a few examples, but have treated them more as curiosities than as objects of art. However, after a year of diligent research, Schwartz has demonstrated that ambrotypes were made on a wide scale throughout Japan for at least three decades after the process was abandoned in the West, and that they are often unexpectedly sophisticated and beautiful.

“I was in Japan on a selling trip,” says Schwartz, “and ran into a collector who surprised me with a couple of ambrotypes which were completely new to me. I was immediately struck by their high quality and intimate, personal nature, which exceeds that of many of the finest Western examples.” The cases were equally amazing. Made of light-colored kiri wood, many were inscribed with elegant calligraphy. Schwartz began researching and collecting Japanese ambrotypes with a passion.

Nineteenth-century photography in Japan has long been known for its Western bias. Both Western and Japanese photographers made albumen prints of Japanese life that often were hand colored, incorporated into fancy albums, and sold to foreigners with deep pockets. The market became so Westernized that Renjo Shimooka, who is often described as Japan’s first commercial photographer, advertised his craft in English. An ambrotype of his second Yokohama studio, which opened in 1868, shows a large sign hanging from the roof, inscribed “Photographer.” A separate sign declares “Pictures Up Stairs.”

In A Century of Japanese Photography, John W. Dower writes that most Japanese photographs directed at the Western market are “not distinguished by any distinctive sense of line and grace. The subject matter of early [Japanese] photography did pick up certain themes already popularized by the native arts of the late feudal period. These included scenes of famous places, depictions of evocative women, portraits of actors, and impressions of artisans and the laboring classes.” The photographs, Dower points out, occasionally had English captions. “Some are plain kitsch: a handsome Gilbert &c Sullivan couple selling a child (they appear to be about to burst into song about their pretty baby in the basket); a warrior performing ‘Harakiri’ in an appropriately tinted print, complete with red blood and green complexion.”

The selection and presentation of this subject matter was heavily influenced by treaty-port tourism and preconceived Western notions about Japan. Western tourists were fascinated by both Japan and photography and created a substantial, ready market for photographs that reflected their often aesthetically trite tastes. “Both as purchasers of the photographs and as photographers themselves,” Dower concludes, “Westerners showed an interest in subjects that Japanese photographers on their own would in all likelihood have ignored.”

Freed from Western market constraints, Japanese photographers made ambrotypes, almost exclusively commissioned portraits of their fellow countrymen. Foremost among them were the samurai, for as Renjo Shimooka recalled, “The warriors of various fiefs, being resolved to fight and prepared to die, asked to be photographed as a memento.” “Indeed, instead of losing one’s shadow,” writes Dower, “one could now hope to leave it to posterity.”

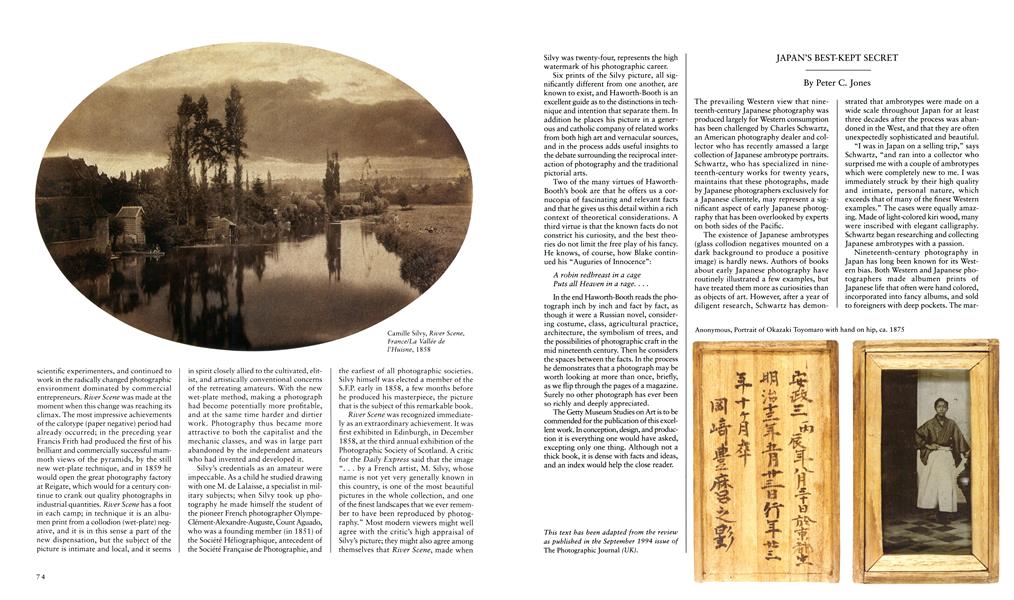

Many compositions are modern and sophisticated in approach, foreshadowing aspects of mid-twentieth-century Western portraiture. In a technique that precedes compositions by August Sander and Irving Penn, the early Japanese ambrotypists positioned their cameras low to the ground to obtain a probing perspective, which is particularly successful with full-figure portraits. Backdrops and sets were especially important pictorial elements. A white backdrop behind the defiant pose of Okazaki Toyomaro (1856-1880, born in Kyoto) divides the picture frame in a modernist composition evocative of Sander’s 1926 portrait of the Wife of the Painter Peter Abelen. Penn’s small-trade workers are anticipated by The Mule Driver.

Almost all ambrotype portraits are classic sixth-plates (2 14 by 3 / inches, literally one-sixth of 6 14 by 8 14 inches full plate) and were shot in photographers’ studios and outdoors on location. Even though the process is the same for an ambrotype positive as a collodion negative, the typical exposure for an ambrotype was somewhat shorter—about five seconds—and the thinner emulsion produced a more luminous positive. Processing took about five minutes, creating almost instantaneous results. Ambrotypes were the Polaroids of the period.

With their precise, luminous compositions, many Japanese ambrotypes stand in stark contrast to their Western counterparts. Japan’s heritage of fine, patient craftsmanship could account for some of the astonishingly rich tonal quality, but most Japanese ambrotypes were made quickly to maximize the profit, an attitude often associated with American photographers. A more likely explanation is that Japanese photographers working in a loose confederation throughout the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries made continuous refinements to a process that Western photographers gave up in the 1860s.

Further evidence of the evolution of Japanese ambrotypes is the nearly universal presentation of ambrotypes in kiri wood boxes. By packaging ambrotypes in these elegant two-part boxes, Japanese photographers took a Western process and made it their own. The idea must have come from Japan’s tradition of storing precious objects, such as combs, hairpins, paintbrushes, and particularly hand-scroll paintings and calligraphy in kiri wood boxes, which were readily available and the perfect size for sixth-plate ambrotypes.

Besides enhancing the presentation of these images, Japanese photographers made technological innovations. Early Japanese ambrotypes, like Western ambrotypes, were framed with the image reversed, and sealed with a second sheet of protective glass. By mounting ambrotypes in boxes, Japanese photographers were able to configure the image directly as a positive. First a dark background was painted or inserted in the bottom of the box. Then, using small wedges to prevent movement, the ambrotype was placed emulsion-side down into the box and the edges were covered with a kiri-wood overmat. The image was now faced in the right direction and the need for a second sheet of glass was eliminated, reducing time and materials costs.

In addition to their light color, which is the perfect background for calligraphy, kiriwood boxes preserve ambrotypes well because they breathe. Consequently, many examples are in excellent condition. Virtually unknown in the West, ambrotypes are the exception to a central irony of Japan’s nineteenth-century photographic history: many of the finest examples of Japanese photography are in Western hands, a result of purchases by tourists who took their prints home where they were safe from the natural and military catastrophes that have afflicted Japan’s major cities over the past 150 years.

Photography first entered Japan when the Dutch traders delivered a daguerreotype camera to Nagasaki merchant Shunnojo Ueno in 1848. The wealthy and educated classes were fascinated by photography and even formed syndicates to raise the large sums required to purchase equipment. Although only one daguerreotype by a Japanese photographer has survived, experiments continued until the arrival of the ambrotype process, sometime between 1854 and 1859. Lord Shimazu made the first known ambrotype, The Three Princesses, in 1858, on the grounds of Kagoshima Castle.

Renjo Shimooka opened his first Yokohama studio in 1862, selling albumen prints to Westerners and ambrotypes to his fellow countrymen. Ultimately, with photographers actively working in cities as well as obscure provinces, the ambrotype process spread throughout Japan, penetrating all layers of society. Some dealers of nineteenth-century Japanese photography claim that at the peak of the ambrotype era almost every family of means owned at least one ambrotype.

Although scattered examples from the late 1850s and early 1860s survive, the ambrotype era really began in 1868, with the great Japanese cultural upheaval known as Meiji. In the Meiji period Western traditions were quickly embraced by the Japanese. Umbrellas and hats were often worn with a traditional kimono, producing what became a common fashion hybrid. Married women were discouraged from shaving their eyebrows, the empress stopped blackening her teeth, and the emperor cut off his topknot. The latest known date for an ambrotype is 1910; perhaps not coincidentally, the Meiji period ended in 1912.

In an 1890 account for a Western journal called the Bulletin, William K. Burton writes that in the 1860s a very small number of Japanese photographers held a virtual monopoly. Kuichi Uchida charged seventy-five dollars for an ambrotype in his Tokyo studio. According to Burton, Uchida had few Japanese customers, in part because of cost and in part due to prevailing Japanese superstitions (i.e., the beliefs that after your first portrait, your shadow will fade; after your second portrait, your life will shorten; the middle of three people photographed together will die early). Still, he got “very high prices from foreigners for photographs of Japanese . . . although he had to pay models.”

According to Japanese photography historian Professor Takeshi-Ozawa, in 1877 there were more than 100 professional photographers in the Tokyo area alone. As the number of photographers increased, the price for an ambrotype portrait dropped from seventy-five dollars to five dollars. Uchida began teaching photography, again for high fees, “under a bond of secrecy” to maintain the remaining market. And he had another source of income: photographic materials. Uchida charged seven dollars and fifty cents for an ounce of silver nitrate, one dollar for an ounce of collodion, two dollars for a pound of iron sulphate, and one dollar for a sheet of albumen paper.

This market manipulation proved unsustainable. By the time Uchida died in 1875, prices had fallen enough to enable even relatively poor people to pay to have their portraits made. Striking evidence comes from a pair of ambrotypes in the Schwartz collection, both with the seal of the Seishindo portrait studio, taken twenty years apart of the same man in the town of Yashima, in Ugo Province. During the Meiji period fewer than three thousand people lived in Yashima, which is located deep in a remote valley off the Japan Sea coast in what is now called Akita Prefecture.

One of the most important and most difficult aspects of Schwartz’s research was translating the calligraphy inscribed on the kiri-wood cases. Schwartz approached Henry D. Smith II, professor of Japanese history at Columbia University; and Hiroshi Onishi, a research curator in the Department of Asian Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. They not only made translations, but also provided vital contextual information about the relationship of ambrotypes to the Meiji period.

One kiri-wood box containing a portrait of a young man features a famous classical Chinese poem (familiarity with classical Chinese works was not uncommon). The poem is a memento mori—a reminder of the inevitability of death—and it was not unusual to present such a poem to a boy about to enter adulthood (a Japanese child came of age at fifteen during the Meiji period). Hiroshi Onishi provides a rough translation:

Even a young boy grows old soon It is bard to achieve one’s learning So study hard now You must not waste even a minute You are still sleeping but Already the grasses on the pond grow Life is but a dream

An ambrotype made on February 14, 1881, of a group of seven men and women in Shimokame-no-cho, a district in remote Akita City, is a Rosetta stone for nineteenthcentury provincial life. The heavy dress indicates that February is a very cold month in this part of Japan. According to Professor Smith, who translated the inscription,

Two of the women come from Akita City, and hence were in effect hosts for the occasion. Three of the men came from Yamagata City, which was over two hundred miles south and required a real journey. The other two, a man and a woman, were from the southern part of the Akita Prefecture, between Akita and Yamagata; although their places are described as “villages, ” these are in prosperous and densely settled areas. The abacus in front and the pose of one (perhaps two) of the men conspicuously writing in what appears to be an account book indicates some sort of merchant nexus. . . . The date of 1881 on the box is confirmed by the place names, which show that it must be after Meiji 4 (1871), when Yuri-gun was created, and before 1883, when Shimokame-no-cho, where the photograph was taken, was completely burned.

The area in question is famous for highquality rice and sake. One might speculate that they were sake dealers celebrating a partnership or an important transaction. What is unclear is the chain of custody of this photograph. It is logical that the ambrotype would have stayed in the host city. If so, how could it have survived the devastating fire? However, it is possible that this is only one of seven ambrotypes made that day, one for each prosperous sitter, and perhaps the only one to survive the intervening century.

Estimating the total production and remaining quantities of Japanese ambrotypes is a bit like describing an elephant with only the trunk and the tail. Schwartz is certain that vast numbers were destroyed by the fires, floods, earthquakes, and wars that have beset Japan’s major cities over the past 150 years. But large areas of rural Japan were spared these calamities, which may explain why ambrotypes are now surfacing in provincial pockets far from Japan’s principal cities.

The Schwartz collection quadrupled in two years, and now numbers more than 150 ambrotypes. He believes that significant quantities may be scattered among families that commissioned them, and continue to be passed down generation by generation, enshrined like votive objects. At the very least, it is clear that during the early Meiji period ambrotypes were viewed on a high cultural level as an important means of preserving family history and tradition. No one can predict what importance history will ultimately attach to Japanese ambrotypes, but there is enough information now to deduce that a major segment of Japanese photographic history has simply been overlooked.

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Peter C. Jones

People And Ideas

-

People And Ideas

People And IdeasParticulars: From The Miller-Plummer Collection

Spring 1984 By Ann Jarmusch -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasAfter Agee

Fall 1988 By J. Ronald Green -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasImage And Memory

Winter 1999 By James Oles -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasMariko Mori, Empty Dream Brooklyn Museum Of Art: April 8-August 15, 1999

Winter 2000 By Lesley A. Martin -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasBill Brandt Portraits

Spring 1983 By Mark Holborn -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasInvitation Au Voyage: Paris—New York

Spring 1978 By Nicholas Callaway