THE POST-COLONIAL BOY

DAVID FRANKEL

Politics is happening inside these landscapes, and painful politics at that. And contemporary people live here.... In images like these the land vomits itself up; it rejects the identity fashioned for it—or the identity fashioned from it, and from its past.

Not long ago I left a New York dinner party in a temper before the coffee was served. The talk had turned to Ireland.

I was a little startled to discover myself outside on the street. It wasn’t that I hadn’t known my attachment to Ireland—born here, part Irish-American, I lived there as a child and visit most years. Utterly unexpected was the degree of feeling, the depth of sensitivity to a conversation I saw as slighting—my feet got me out of there before I’d decided to leave.

So it may go among emigrants. (Although, again, it is a little startling to think of oneself as an emigrant, emigration being naturalized as the Irish condition.) But we are just as likely to have the opposite experience, stunned not by closeness but by distance. As a teenager in London, where my family moved when I was ten, I nursed my Irish accent even as it faded. London was a cold place, Ireland a warm memory; though eventually you might have thought I’d grown up somewhere east of Ireland but west of Wales (somewhere impossible, that is), I believed I spoke as an Irishman and, when I was sixteen or seventeen, told a Dublin friend so. She burst out laughing. My accent came from a place that doesn’t exist.

Which is appropriate, really, and okay. It’s not as if the place you remember is ever the place that is. That’s memory’s given.

What was this place I remember, which doesn’t exist? In Dublin in the fifties and early sixties, a man and a horse delivered milk in the morning in glass bottles. There were few cars and many bikes. The city was quiet, safe: at seven or eight, when I wanted to go to a bookshop, I took a bus across town by myself. (I got lost, it was terrifying.) We played in the street all day, unwatched.

Dublin was small enough that it seemed you could be outside it—in the mountains, by the sea—in twenty minutes wherever you were. We lived in the mountains for a while, in a stonefloored cottage, now a stable. It stood at the edge of a field of dock and nettle, cows and a bull. Once a toad got into the scullery, leaping as high as my head. (I was little.) The cottage was the gatehouse of an old Anglo-Irish estate; every year there was a hunt—horses, dogs, a crowd, red coats against the green, supposedly a fox. The field looked all the way across Dublin to the bay.

In the summers we’d go to the West. The romance of names, as we drove: Kildare, Galway, Connemara, Mayo, Achill. Here there were even fewer cars; people used donkeys for hauling and riding. On Sundays they might go to church in a horse and trap. They let me come to the ceilidh, a wild party in a pub. Donkeys wandered the beaches. Lobsters crawled the floor of the hotel. A house we stayed in was lit, elegantly, by gas lamps; and one day Mr. Thornton’s hat blew off, into the sea.

Needless to say, the sky was blue and clear, the sun hot. The humidity, low. (In fact I do remember dramatic summer sunburns.)

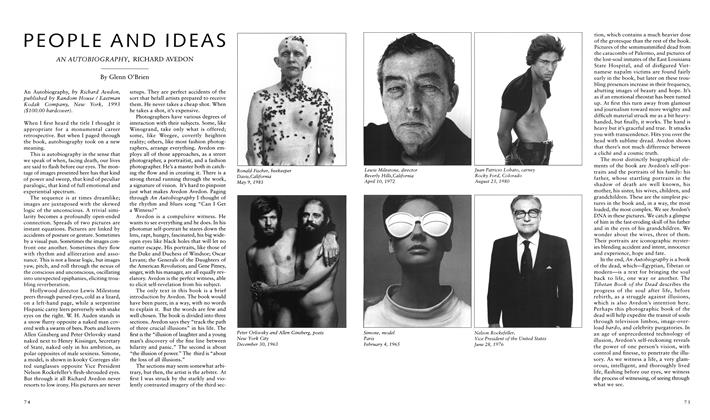

Collecting Turf from the Bog, Connemara, County Galway— how different is that from my Ireland? A picture postcard by John Hinde, it does, after all, have a donkey in it. Notice the reds: Hinde loved red. He thought it caught the tourist’s eye on the display racks. When he photographed London, he’d make sure a London bus was in the frame. Here he must have liked the girl’s shirt, and both children’s hair, which may have been why he picked them.

Or maybe Martin Parr’s Horseracing, Glenbeigh, County Kerry. No donkey. Horse.

(continued on page 32)

Perhaps Parr remembered the Synge play The Playboy of the Western World, which turns on a horse race along a western beach. The Irish have a myth of the West, and Synge, with Yeats and Lady Gregory and other writers of his time (late nineteenth, early twentieth century), is partly responsible for it. The Playboy is a poetical piece, crafted, witty, poignant. It might seem to be what art historians talking about painting call a genre work: the colorful common people, their rude courtships, their rowdy pleasures, their folklore, their sympathy with nature. All this is in the play, but Synge didn’t mean to condescend. The Irish were getting ready to free themselves, finally, of the British occupation. (Having lasted centuries, it ended fifteen or so years after Synge wrote.) Who would they be, what would they be, on their own? The Playboy of the Western World says: Ireland has its own life. Its richness is clear from its speech; and it has nothing to do with England. The play’s story (a son tries to kill his father, who won’t die) may be allegorically suggestive, but the crucial public issue of the time—the relationship with Britain—isn’t discussed.

OUR LADY OF ARDBOE

I

Just there, in a corner of the whin-field, Just where the thistles bloom. She stood there as in Bethlehem One night in nineteen fifty-three or four.

The girl leaning over the half-door Saw the cattle kneel, and herself knelt.

II

I suppose that a farmer’s youngest daughter Might, as well as the next, unravel The winding road to Christ’s navel.

Who’s to know what’s knowable? Milk from the Virgin Mother’s breast, A feather off the Holy Ghost? The fairy thorn? The holy well?

Our simple wish for there being more to life Than a job, a car, a house, a wife— The fixity of running water.

For I like to think, as I step these acres, That a holy well is no more shallow Nor plummetless that the pools of Shiloh, The fairy thorn no less true than the Cross.

III

Mother of our Creator, Mother of our Saviour, Mother most amiable, Mother most admirable. Virgin most prudent, Virgin most venerable, Mother inviolate, Mother undefiled.

And I walk waist-deep among purples and golds With one arm as long as the other.

—p. M.

WHY BROWNLEE LEFT

Why Brownlee left, and where he went, Is a mystery even now. For if a man should have been content It was him; two acres of barley, One of potatoes, four bullocks, A milker, a slated farmhouse. He was last seen going out to plough On a March morning, bright and early.

By noon Brownlee was famous; They had found all abandoned, with The last rig unbroken, his pair of black Horses, like man and wife, Shifting their weight from foot to Foot, and gazing into the future.

—p. M.

In the summers we’d go to the West. The romance of names, as we drove: Kildare, Galway, Connemara, Mayo, Achill. Here there were even fewer cars; people used donkeys for hauling and riding. On Sundays they might go to church in a horse and trap. They let me come to the ceilidh, a wild party in a pub. Donkeys wandered the beaches. Lobsters crawled the floor of the hotel.

(continued from page 14)

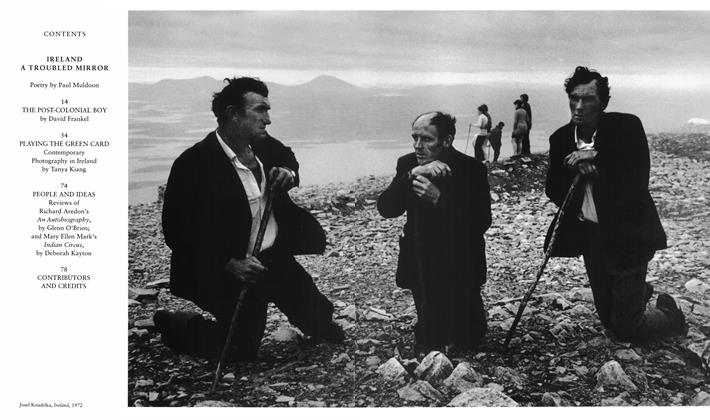

The Irish myth of the West is a kind of reverse of the American one: here, a West imagined as vacant, waiting; in Ireland, a West once full of people. (Even after the nineteenth-century famines and emigrations began emptying it out, the government called it the “Congested Districts.”) In the American myth the West’s first peoples are at worst hostile, at best inconsequential; in the Irish, they’re the guardians of the country’s language, of its oral history, of its Gaelic self. Here, as we receive the myth, watch the movie, we move west with invaders from the east, into an open space of opportunity.There we are penned in from the east, in a land at once stronghold and prison.

The myths aren’t really opposite: it’s just that the American myth is told from the invaders’ point of view. In American terms, the Irish are the Indians.

On a New York terrace, a woman from Virginia told me she had visited Ireland once, as a tourist, and had loved it. I asked her why: “Because it’s tragic,” she said, “and because of their sense of history. It reminds me of the South.” Ireland is like the American West, Ireland is like the American South: Ireland is very like a whale. But what the South and the West share, and share with Ireland, is a history of bitter struggle over the land, incompletely resolved, and vividly alive in the mind.

On Inishbofin, an island off far western Galway, a man pointed out to me, a child then, a rock offshore in the harbor. On “the priest’s rock,” he told me, three hundred years before, Protestant soldiers from the east had chained a Catholic priest at low tide, then watched as the water rose. Elsewhere, “the priest’s leap”: the priest had jumped off a cliff rather than be taken alive. I can’t say that it happened, can’t say that it didn’t. What’s clear is the attitude: landscape and history are one, and are powerful. Imagine walking Gettysburg with a Civil War nut—but this was just a rock in the ocean, and someone passing by.

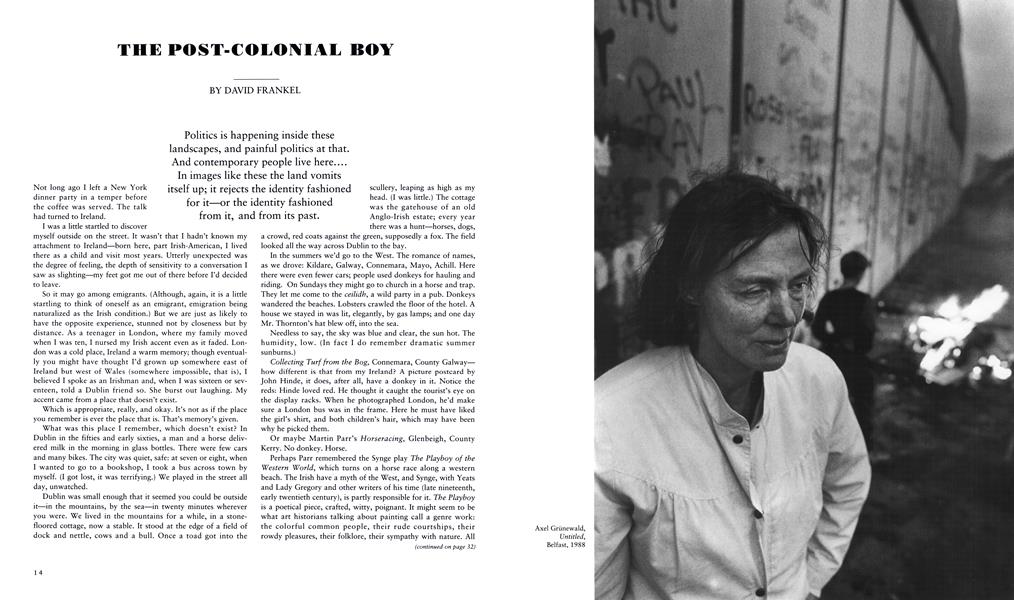

So Paul Seawright, when he photographs a dumping ground for “sectarian murder,” makes sure you can see the dolmen in the field, and the grass. The captions tell you you’re looking at a tourist spot, a beauty spot. Or he shows you a swell of hillside, a clutch of flowers, a stretch of sky. The bodies have already been taken away. Paul Graham photographs a townscape as a kind of flattened, thin version of the picturesque, in fact a dismal pictorial failure—the hills that might shape the photo way off in the distance, everything flat, no one around, in the foreground the graffiti, in Hinde red: BEWARE. Politics is happening inside these landscapes, and painful politics at that. And contemporary people live here, perhaps in the crowded, specific clutter of the family lovingly photographed by Anthony Haughey; or in the brutal circumstances of the northern conflict, or perhaps as mohawk-wearing sightseers enjoying the sun on a fishing-village pier. In images like these the land vomits itself up; it rejects the identity fashioned for it—or the identity fashioned from it, and from its past.

Joyce, famously, wrote of forging in the smithy of his soul the uncreated conscience of his race. The line is often taken to describe what the artist does, anywhere, but the time of its writing, midway through the fifteen years between The Playboy and independence, suggests another reading: in the difficult, contested expulsion of the colonial, the need to build something for nation, people, to be. As it turned out, the foundations available were history and land—a history part recent, part ancient, part mythic, a landscape of striking pictorial passages. Social fact— the ground largely rural, the economy largely agrarian, industry largely gutted or stillborn under British rule—channeled the construction. The product: a contender in the marketplace of modern tourism.

The remark, though true, is cheap. It implies an easy kind of transaction. Not long ago at a Dublin dinner party, telling Irish friends I was on my way to a vacation in the West, I saw them exchange a quick look. The Irish are well aware of the tensions of their modern state. All the way through this book, you watch the argument. □

THE CENTAURS

I can think of William of Orange, / Prince of gasworks-wall and gable-end. A plodding, snow-white charger / On the green, grassy slopes of the Boyne, The milk-cart swimming against the current

Of our own backstreet. Hernán Cortes / Is mustering his cavalcade on the pavement, Lifting his shield like the lid of a garbage-can. / His eyes are fixed on a river of Aztec silver, He whinnies and paws the earth

For our amazement. And Saul of Tarsus, / The stone he picked up once has grown into a hoof. He slings the saddle-bags over his haunches, / Lengthening his reins, loosening his girth, To thunder down the long road to Damascus.

—p. M.

Predictable as the gift of the gab or a drop of the craythur he noses round the six foot deep crater.

Oblivious to their Landrover’s olive-drab

and the Burgundy berets of a snatch-squad of Paratroopers. Gallogly, Gollogly, otherwise known as Golightly, otherwise known as Ingoldsby, otherwise known as English, gives forth one low cry of anguish and agrees to come quietly.

They have bundled him into the cell for a strip -search. He perches

on the balls of his toes, my, my, with his legs spread till both his instep arches fall.

He holds himself at arm's length from the brilliantly Snowcem-ed wall, a game bird hung by its pinion tips till it drops, in the fullness of time, from the mast its colours are nailed to.

-P. M.

DON’T HEAR WHAT YOU HEAR

DON’T SEE WHAT YOU SEE

DON'T BREATHE A WORD OF IT

DON'T LET HIM INTO YOUR PUSS

little did I think that S____ would turn to me one night: `The only Saracen I know's a Saracen tank with a lion rampant on its hood;

from Aghalane to Artigarvan to Articlave the Erne and the Foyle and the Bann must run red'; that must have been the year Twala's troops were massacred.

-P. M.

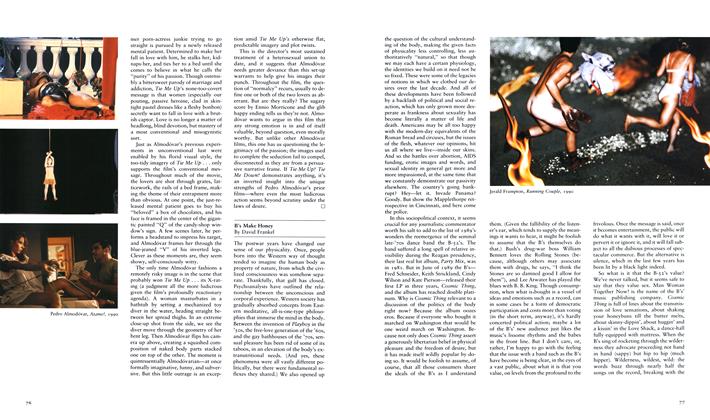

Brian, a Loyalist youth from Tiger’s Bay in Belfast, prepares for another day with his nighttime protection safely within reach. He lives within two hundred yards of a Nationalist estate that staunchly backs the IRA.

Making a flame thrower using hairspray might seem violent and destructive, but to Brian it's just another way to fill an empty day.

Not fighting, but “playing” (according to Brian) with girlfriend Sharon, 16.

Brian’s first time at a disco. Fearful that Nationalists might show up looking for a fight, this night he goes with a group of his buddies.

THE SIGHTSEERS

My father and mother, my brother and sister and I, with uncle Pat, our dour best-loved uncle, had set out that Sunday afternoon in July in his broken-down Ford

not to visit some graveyard—one died of shingles, one of fever, another’s knees turned to jelly— but the brand-new roundabout at Ballygawley, the first in mid-Ulster.

Uncle Pat was telling us how the B-Specials had stopped him one night somewhere near Ballygawley and smashed his bicycle

and made him sing the Sash and curse the Pope of Rome. They held a pistol so hard against his forehead there was still the mark of an O when he got home.

—p. M.

Tuesday 30th January 1973 "The car travelled to a deserted tourist spot known as the Giants Ring. The 14 year old boy was made to kneel on the grass verge, his anorak was pulled over his head, then he was shot at close range, dying instantly."

Sunday July 9, 1972, "The 31 year old man was found under some bushes in Cavehill Park. He had been shot dead. The police believe it to have been a sectarian murder."

Monday 3rd July 1972 “The man had left home to buy some drink; he was found later on waste ground nearby. He had been badly beaten and it seems he had been tied to a chair with barbed wire before being shot through the head.”

Friday May 25, 1973, "The murdered man's body was found lying at the Giants Ring beauty spot, once used for pagan rituals. It has now become a regular location for sectarian murder."

Tuesday, April 3, 1973, "Late last night a 28 year old man disappeared from a pub. It wasn't until this morning that his body was found abandoned in a quiet park on the coast."

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

David Frankel

-

People And Ideas

People And IdeasB's Make Honey

Fall 1990 By David Frankel -

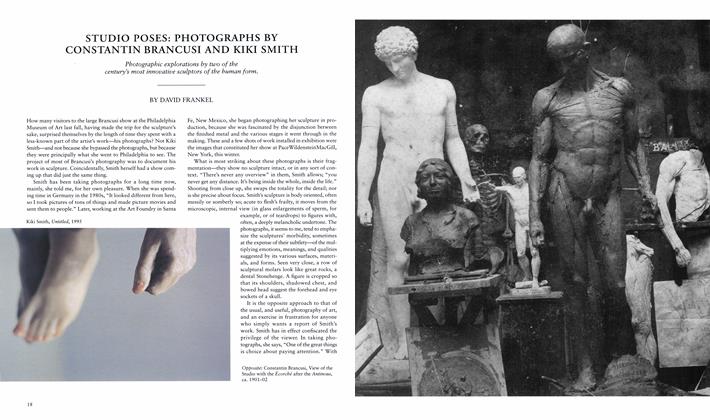

Studio Poses: Photographs By Constantin Brancusi And Kiki Smith

Fall 1996 By David Frankel -

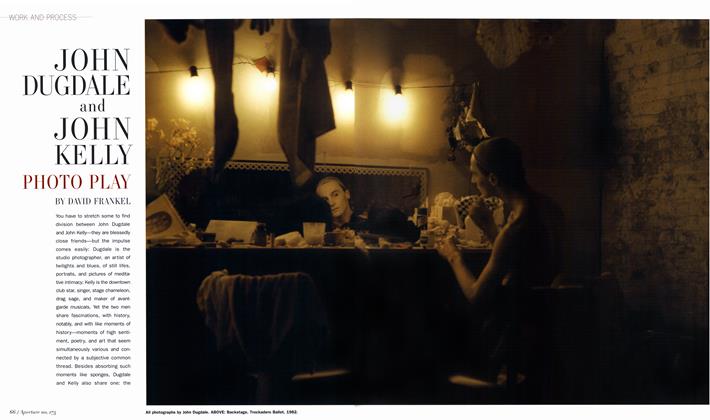

Work And Process

Work And ProcessJohn Dugdale And John Kelly

Winter 2003 By David Frankel -

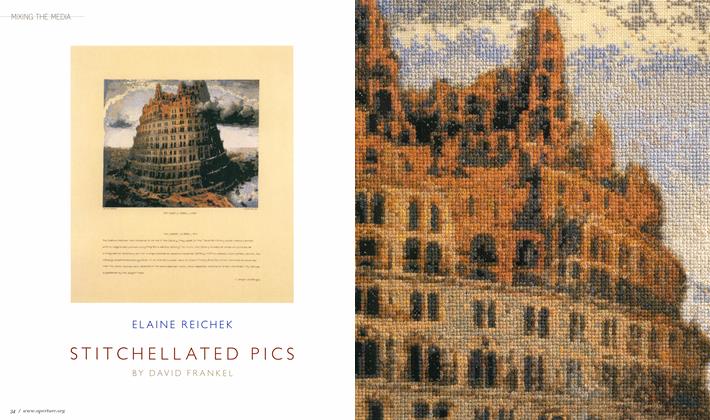

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaElaine Reichek Stitchellated Pics

Summer 2004 By David Frankel -

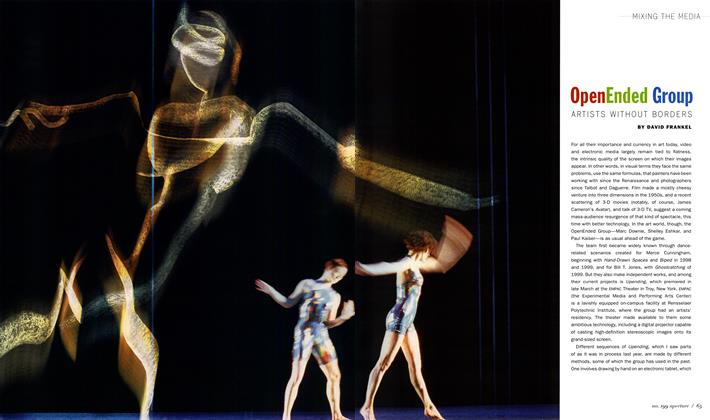

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaOpen Ended Group: Artists Without Borders

Summer 2010 By David Frankel