People And Ideas

A Symbiotic Relationship: Collecting And The History Of Italian Photography

Summer 1993 Carlo BertelliA Symbiotic Relationship: Collecting And The History Of Italian Photography Carlo Bertelli Summer 1993

A SYMBIOTIC RELATIONSHIP: Collecting and the History of Italian Photography

PEOPLE AND IDEAS

Carlo Bertelli

In 1961 a short survey of the history of Italian photography, compiled by Lamberto Vitali, appeared as an appendix to the Italian translation of Peter Pollack’s History of Photography from Antiquity to Today. An appendix was necessary, as Pollack’s book scarcely gave mention of what had happened in Italian photography since the first daguerreotypes were made, as early as 1839.

In his book The Rare Art, Joseph Alsop makes the point that there could not be a history of art without art collecting. The evolution of Italian historiography bears this statement out: a number of historians were also collectors of the objects of their research. Vitali, for example, collected not only photographs, but also art and antiquities. In fact, it was his interest in a nineteenth-century painter, Federico Faruffini, that led Vitali to early Italian photography. Faruffini was also a photographer, and Vitali became interested in the medium after discovering and acquiring a number of his photographs. In 1935, he wrote a piece on Faruffini’s work as a photographer for Emporium, an art magazine that Vitali himself edited.

Photography by painters, either for their own use, or—as was the case with Faruffini—to sell to colleagues (most frequently images of nudes for use as models), was not an uncommon practice in nineteenth-century Europe, but this activity had little to do with photography as a profession or as an art in its own right. While painters might demonstrate an aesthetic sensibility in their photographs, they remained ensconced in a world that centered on painting.

The true art of collecting—and that which first illuminated the evolution of Italian photography—was and still is best exemplified by the all-consuming passion of the romanisti, or devotees of Roman curiosities and history. In 1956 a distinguished romanista, Silvio Negro, wrote a fascinating book on the “Fourth Rome,” which examined the Republican urbs in the imperial city, the papal metropolis. His book, entitled Quarta Roma, was the product of a lifetime of work. Informative and brilliant, it managed to gather the minutest details of Roman daily life from a variety of angles, giving a lively picture of a period of transition. Negro rediscovered a number of photographers active in Rome from the early 1900s and includes in the book particulars of their day-to-day lives, as well as images by these pioneers. (Negro was not the only romanista who was both a collector and a connoisseur. The archaeologist Valerio Cianfarani compiled a notable collection, as has Piero Becchetti, for example. )

Thus it was in studying the history of the last days of papal Rome that Italian photography began to be investigated as a historical phenomenon. This may seem surprising to those unfamiliar with Italian history: papal Rome was, after all, the center of a reactionary, theocratic, and medieval state. What role could photography possibly have played? As we well know from the experience of these final decades of the twentieth century, technological progress is not necessarily indicative of an advanced, “progressive” society. And so, one should be surprised neither that there were technological advances made in papal Rome, nor that it was seen as desirable, perhaps even expedient, to record this new technology and its most common applications through photography. Pius IX was especially pleased to have photographs of the new railways and steamboats (just as years later, Mussolini would use the medium to celebrate achievements in aviation, among other things). His successors were equally open to photography: one ceiling in the Musei Vaticani introduces what is perhaps the first representation of a photographic camera made in fresco, painted by commission under Pope Leo XIII.

During this fin-de-siècle period, Rome was unquestionably the most cosmopolitan city in Italy. Nearly all the civilized states had their representatives there. Pilgrims, sightseers, and adventurers also came flocking to Rome, which was the inevitable goal of the Grand Tour. Tourism is, of course, a highly visual experience and, since the advent of the camera, tourists have been hungry for photographs. Furthermore, it seems that there was no event in Rome, no trace of her past, that did not seem photogenic to someone—even the trenches and cannons of the 1849 revolution became the subjects of photographic reportage.

There could not be a history of art without art collecting. The evolution of Italian historiography bears this out.

Italy also attracted art historians—the disciples of a new branch of research—as well as hordes of archaeologists. Soon, photo studios began to specialize in these particular areas of documentation, which were to occupy much of Italian photographic production for many decades. The pictures were not collected or made for the sake of photography, but as reminders, records of the original site or artwork. The photographers’ skill was in remaining as anonymous as possible.

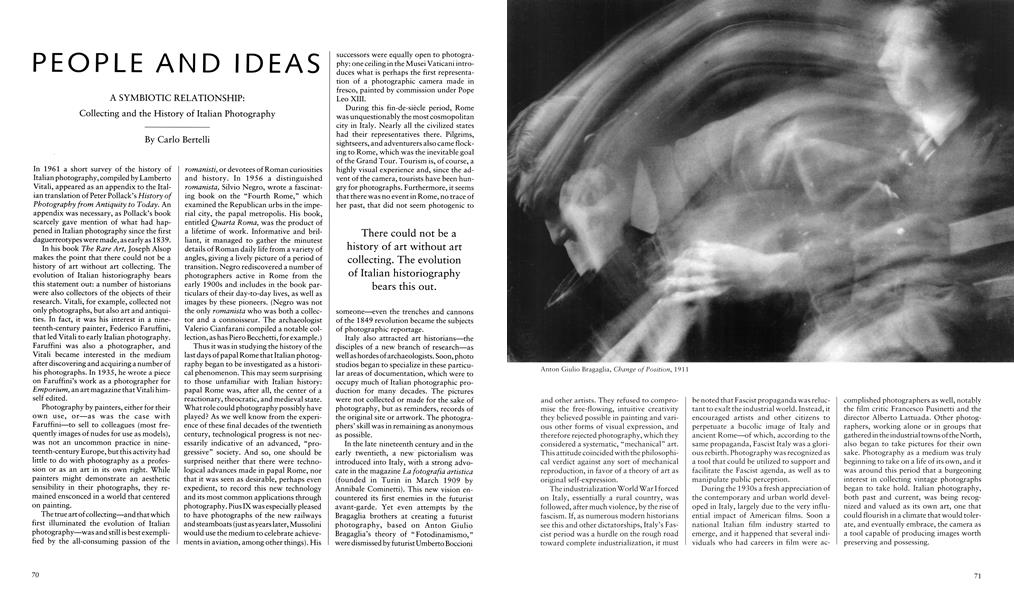

In the late nineteenth century and in the early twentieth, a new pictorialism was introduced into Italy, with a strong advocate in the magazine La fotografía artística (founded in Turin in March 1909 by Annibale Cominetti). This new vision encountered its first enemies in the futurist avant-garde. Yet even attempts by the Bragaglia brothers at creating a futurist photography, based on Anton Giulio Bragaglia’s theory of “Fotodinamismo,” were dismissed by futurist Umberto Boccioni and other artists. They refused to compromise the free-flowing, intuitive creativity they believed possible in painting and various other forms of visual expression, and therefore rejected photography, which they considered a systematic, “mechanical” art. This attitude coincided with the philosophical verdict against any sort of mechanical reproduction, in favor of a theory of art as original self-expression.

The industrialization World War I forced on Italy, essentially a rural country, was followed, after much violence, by the rise of fascism. If, as numerous modern historians see this and other dictatorships, Italy’s Fascist period was a hurdle on the rough road toward complete industrialization, it must be noted that Fascist propaganda was reluctant to exalt the industrial world. Instead, it encouraged artists and other citizens to perpetuate a bucolic image of Italy and ancient Rome—of which, according to the same propaganda, Fascist Italy was a glorious rebirth. Photography was recognized as a tool that could be utilized to support and facilitate the Fascist agenda, as well as to manipulate public perception.

During the 1930s a fresh appreciation of the contemporary and urban world developed in Italy, largely due to the very influential impact of American films. Soon a national Italian film industry started to emerge, and it happened that several individuals who had careers in film were accomplished photographers as well, notably the film critic Francesco Pusinetti and the director Alberto Lattuada. Other photographers, working alone or in groups that gathered in the industrial towns of the North, also began to take pictures for their own sake. Photography as a medium was truly beginning to take on a life of its own, and it was around this period that a burgeoning interest in collecting vintage photographs began to take hold. Italian photography, both past and current, was being recognized and valued as its own art, one that could flourish in a climate that would tolerate, and eventually embrace, the camera as a tool capable of producing images worth preserving and possessing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Poetica E Poesia

Summer 1993 By Roberta Valtorta -

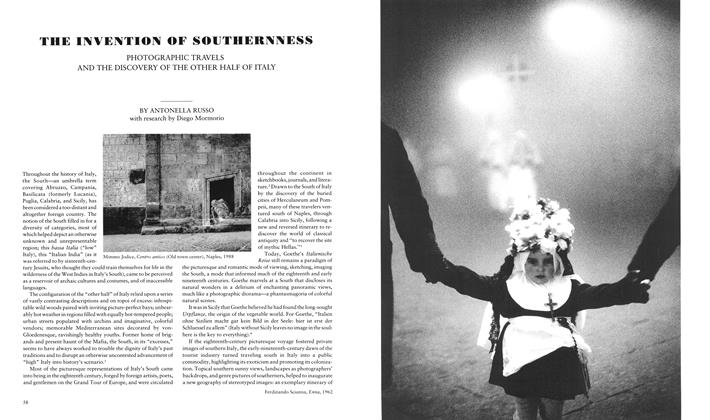

The Invention Of Southernness

Summer 1993 By Antonella Russo -

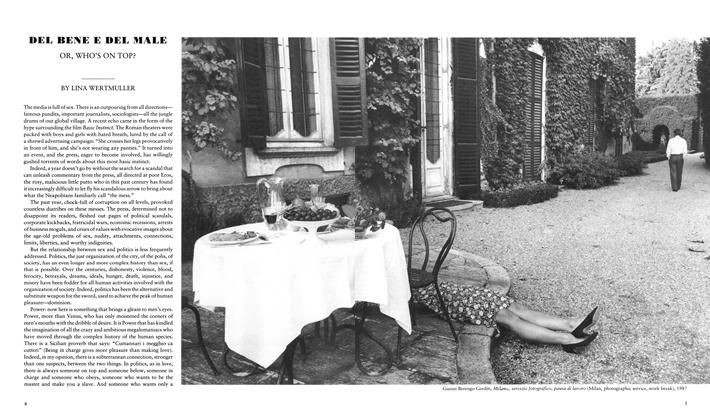

Del Bene E Del Male

Summer 1993 By Lina Wertmuller -

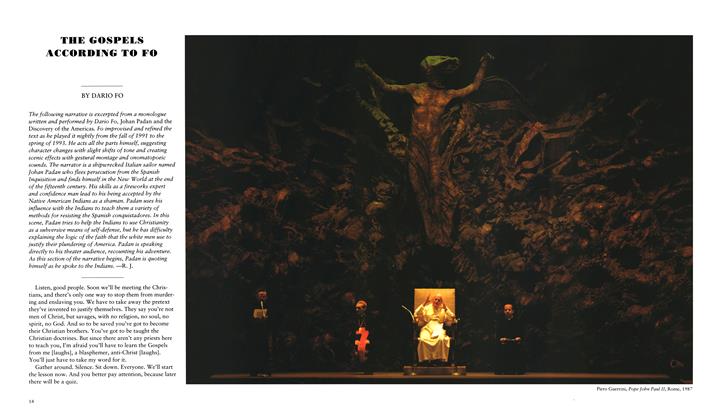

The Gospels According To Fo

Summer 1993 By Dario Fo -

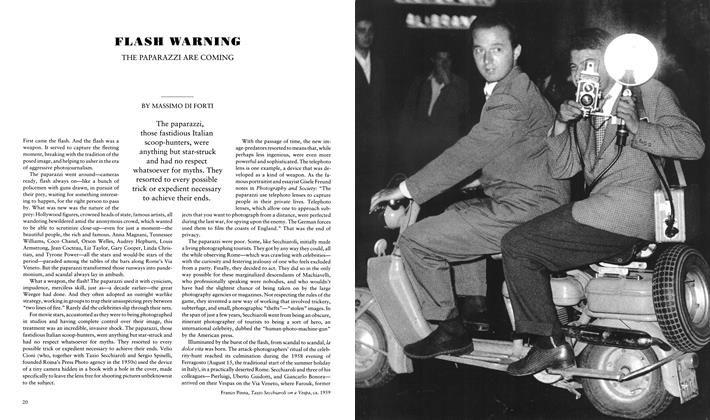

Flash Warning

Summer 1993 By Massimo Di Forti -

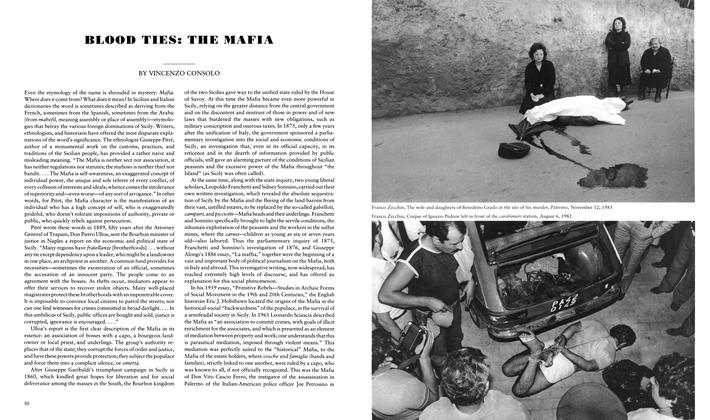

Blood Ties: The Mafia

Summer 1993 By Vincenzo Consolo

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

People And Ideas

-

People And Ideas

People And IdeasAaron Siskind, 1903-1991

Spring 1991 -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasA Gathering Of Friends

Spring 1977 By Anita V. Mozley -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasA Letter From Graz

Spring 1983 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasWilliam Morris: The Earthly Paradox

Winter 1997 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasSarah Charlesworth Retrospective At Site Santa Fe

Spring 1998 By Mary-Charlotte Domandi -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasA One-Woman Show: An Interview With Marie Yolande St. Fleur

Winter 1992 By Rebecca Busselle