THE FINAL FRONTIER?

PEOPLE AND IDEAS

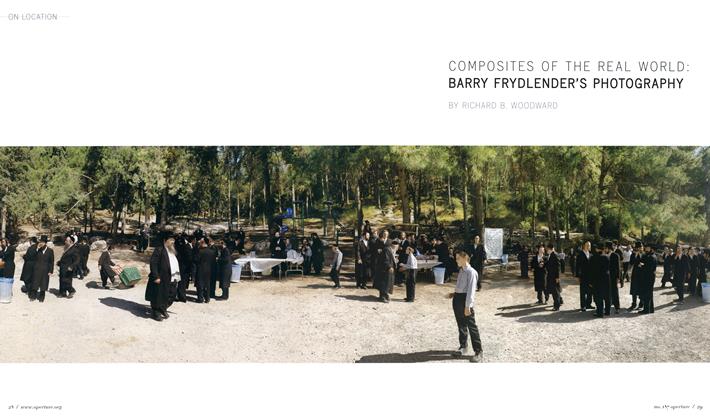

Richard B. Woodward

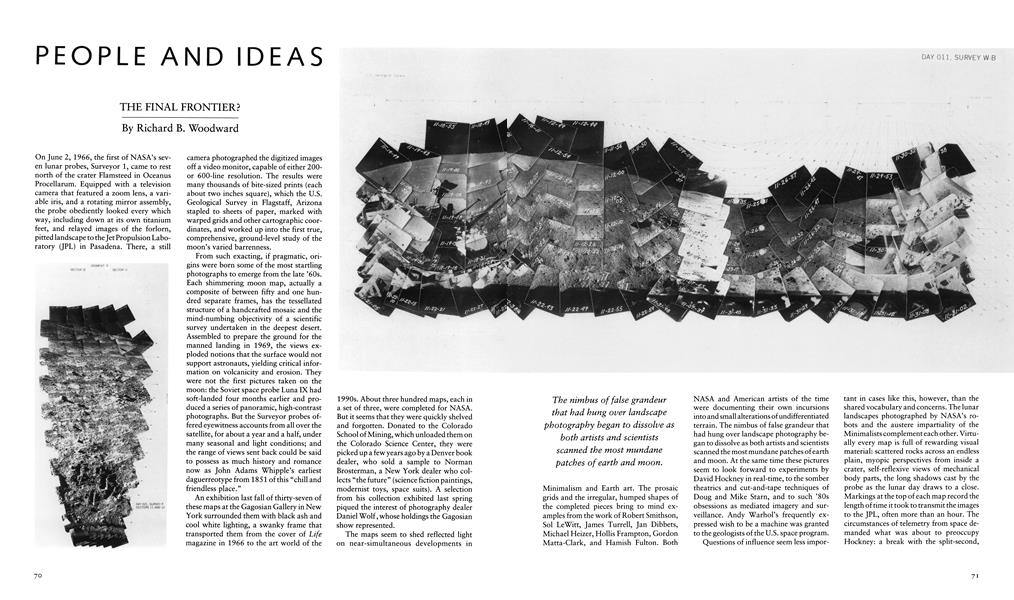

On June 2, 1966, the first of NASA’s seven lunar probes, Surveyor 1, came to rest north of the crater Flamsteed in Oceanus Procellarum. Equipped with a television camera that featured a zoom lens, a variable iris, and a rotating mirror assembly, the probe obediently looked every which way, including down at its own titanium feet, and relayed images of the forlorn, pitted landscape to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena. There, a still camera photographed the digitized images off a video monitor, capable of either 200or 600-line resolution. The results were many thousands of bite-sized prints (each about two inches square), which the U.S. Geological Survey in Flagstaff, Arizona stapled to sheets of paper, marked with warped grids and other cartographic coordinates, and worked up into the first true, comprehensive, ground-level study of the moon’s varied barrenness.

From such exacting, if pragmatic, origins were born some of the most startling photographs to emerge from the late ’60s. Each shimmering moon map, actually a composite of between fifty and one hundred separate frames, has the tessellated structure of a handcrafted mosaic and the mind-numbing objectivity of a scientific survey undertaken in the deepest desert. Assembled to prepare the ground for the manned landing in 1969, the views exploded notions that the surface would not support astronauts, yielding critical information on volcanicity and erosion. They were not the first pictures taken on the moon: the Soviet space probe Luna IX had soft-landed four months earlier and produced a series of panoramic, high-contrast photographs. But the Surveyor probes offered eyewitness accounts from all over the satellite, for about a year and a half, under many seasonal and light conditions; and the range of views sent back could be said to possess as much history and romance now as John Adams Whipple’s earliest daguerreotype from 1851 of this “chill and friendless place.”

An exhibition last fall of thirty-seven of these maps at the Gagosian Gallery in New York surrounded them with black ash and cool white lighting, a swanky frame that transported them from the cover of Life magazine in 1966 to the art world of the 1990s. About three hundred maps, each in a set of three, were completed for NASA. But it seems that they were quickly shelved and forgotten. Donated to the Colorado School of Mining, which unloaded them on the Colorado Science Center, they were picked up a few years ago by a Denver book dealer, who sold a sample to Norman Brosterman, a New York dealer who collects “the future” (science fiction paintings, modernist toys, space suits). A selection from his collection exhibited last spring piqued the interest of photography dealer Daniel Wolf, whose holdings the Gagosian show represented.

These orphaned images looked peculiar at Gagosian, where they carried an inflated price tag of $10,000 apiece. Speculating on their value may very well taint their bold beauty. They are first and foremost a group of documents from the early space age. However much they may belong in the next museum retrospective on photography, performance, and Minimalist art from the ’60s, these are maps of rocks made by geologists, Edenic in their innocence. One did not know whether to be grateful that art dealers have rescued what America’s science establishment had so cavalierly thrown away, or to be worried that such a display will grossly distort the nature of their value and intent.

The maps seem to shed reflected light on near-simultaneous developments in Minimalism and Earth art. The prosaic grids and the irregular, humped shapes of the completed pieces bring to mind examples from the work of Robert Smithson, Sol LeWitt, James Turrell, Jan Dibbets, Michael Heizer, Hollis Frampton, Gordon Matta-Clark, and Hamish Fulton. Both NASA and American artists of the time were documenting their own incursions into and small alterations of undifferentiated terrain. The nimbus of false grandeur that had hung over landscape photography began to dissolve as both artists and scientists scanned the most mundane patches of earth and moon. At the same time these pictures seem to look forward to experiments by David Hockney in real-time, to the somber theatrics and cut-and-tape techniques of Doug and Mike Starn, and to such ’80s obsessions as mediated imagery and surveillance. Andy Warhol’s frequently expressed wish to be a machine was granted to the geologists of the U.S. space program. monolithic point of view. Changes in printing paper, from matte to glossy, indicate that scientists sought moody effects as well as topographic precision. Their handiwork can look as richly metaphoric and wellcrafted as one of Timothy O’Sullivan’s western landscapes.

The nimbus of false grandeur that had hung over landscape photography began to dissolve as both artists and scientists scanned the most mundane patches of earth and moon.

Questions of influence seem less important in cases like this, however, than the shared vocabulary and concerns. The lunar landscapes photographed by NASA’s robots and the austere impartiality of the Minimalists complement each other. Virtually every map is full of rewarding visual material: scattered rocks across an endless plain, myopic perspectives from inside a crater, self-reflexive views of mechanical body parts, the long shadows cast by the probe as the lunar day draws to a close. Markings at the top of each map record the length of time it took to transmit the images to the JPF, often more than an hour. The circumstances of telemetry from space demanded what was about to preoccupy Hockney: a break with the split-second,

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Richard B. Woodward

People And Ideas

-

People And Ideas

People And IdeasAutobiography Of Larry Clark

Spring 1984 -

People And Ideas

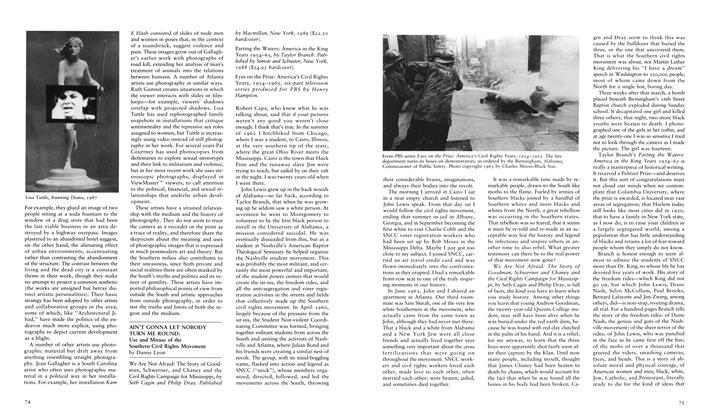

People And IdeasAin't Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Round: Use And Misuse Of The Southern Civil Rights Movement

Summer 1989 By Danny Lyon -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasSpe At Twenty-One

Spring 1984 By John Grimes -

People And Ideas

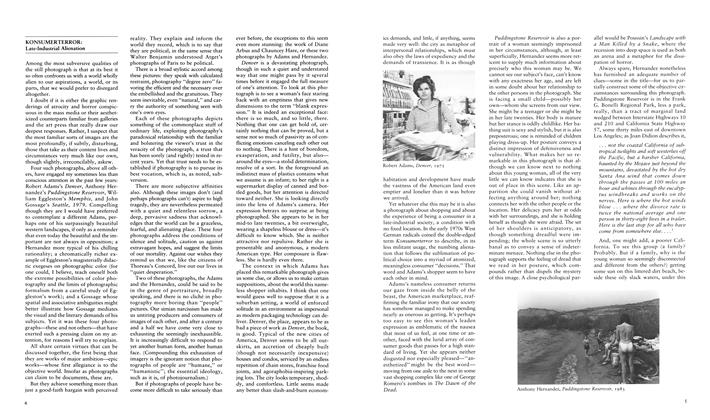

People And IdeasKonsumerterror: Late-Industrial Alienation

Fall 1984 By Lewis Baltz -

People And Ideas

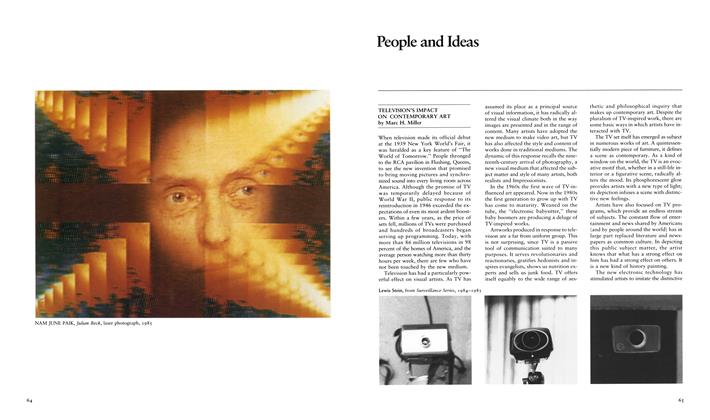

People And IdeasTelevision's Impact On Contemporary Art

Spring 1987 By Marc H. Miller -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasSarah Charlesworth Retrospective At Site Santa Fe

Spring 1998 By Mary-Charlotte Domandi