VODOU CARNIVAL

Donald Cosentino

Maya Deren's beautiful eyes stare out dreamily from the back cover of Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti. They look at once innocent and too knowing. She had used them keenly as avantgarde filmmaker with Luis Bunuel, and then for three years in the late '40s as acolyte in a Vodou temple in the Haitians backcountry called Cul-de-Sac. She wrote about what she saw: a neo-paganism to which she could give her whole filmmaker-dance-ethnographerGreenwich Village soul. And in “White Darkness,” the final chapter of Divine Horsemen, Deren describes her experience of possession by the loa Erzulie Freda, mistress-lover of the Vodou pantheon:

There is nothing anywhere except this. There is no way out. The white darkness moves up the veins of my leg like a swift tide rising, rising; is a great force which I cannot sustain or contain, which, surely, will burst my skin. It is too much, too bright, too white for me; this is darkness. “Mercy!” I scream within me. I hear it echoed by the voices, shrill and unearthly: “Erzulie!” The bright darkness floods up through my body, reaches my head, engulfs me. I am sucked down and exploded upward at once. That is all.

Deren clearly crossed the line anthropology had drawn for itself in the nineteenth century. She became a “native” in the forbidden paradigm: white artist surrendering to black sensuality—Jungle Fever! What academia feared, a more imaginative coterie found irresistible. The flip side of Vodou's ol' black magic is the gnostic vision of an enchanted island. A small stream of artists and scholars has followed Deren, seeking to replicate her vision. Spurning the predictable Haiti conjured by zombie-chat available on Geraldo or Donahue, they were lured by the poetry of Deren’s encounters with Erzulie, and by her Vodou footage surrealistically edited and released in 1985 as the film Divine Horsemen. With heads tilted (like Bernini’s St. Teresa) in ineffable ecstasies—eyes rolled back to interior apparitions—Deren’s worshippers pirouette with sequined flags, castrate goats, turn their shoulders in the yanvalou, thrust their pelvises in the banda—and become the pantheon of their deities in the most powerful trance-possession footage ever shot.

Near the end of Divine Horsemen, after Guede, the loa of death and sexuality, has disordered a Vodou service in his usual way, the camera suddenly switches from ecstasy in the Cul-de-Sac temple to hijinks on streets of Port-au-Prince. In this peculiar montage, it is now Carnival. Harlequins in satin jumpsuits stand at crossroads whipping the ground. Floats pass by with mulatto beauty queens. A bogus diplomat in top hat and morning coat is tracked by a cardboard movie camera. Marchers appear with gigantic papiermaché heads: hydrocephalic mockeries of the bourgeoisie. A large contingent suddenly appears carrying signs advertising “EX-LAX.” And always, amidst these diverse groups, Guede pops up, his face all white except for his sunglasses. Mr. Bones in black top hat and smoking jacket; the divine undertaker bumping and grinding with the revelers. At the very end of the film the images grow fuzzy. They lose focus, like the dying pages of Diane Arbus’s monograph, until all is reduced to Guede’s skeletal leer, frozen in a final frame.

I visited Port-au-Prince Carnival in February 1991, with Deren’s images very much in mind. The town was in a mood to celebrate, perhaps for the first time since the late 1940s when Dumarsais Estimé became president and Deren shot her film. In Estimé the street Creoles sensed a champion against the mulattoes who lived in the hills. But sitting in his cabinet was an obscure country doctor, François Duvalier. In 1957 Papa Doc Duvalier wrested power, and then passed it on to his flaccid son Baby in 1971. Together père et fils transformed the state into a Grade B horror film. Papa Doc assumed Guede’s funereal attire, even his nasalized speech. Baby became President-for-Life at age nineteen. After a few years as boulevardier, Baby married the rapacious Michèle Bennett and settled into a life of routinized terror. During those Duvalier years what remained of Carnival’s masquerading tradition was seized by the Tontons Macoutes, who became real life monsters in Ray-Bans. Had Deren’s fading image of leering Guede foreshadowed that descending night?

THIS IS THE REAL FESTIVAL OF REVERSALS, NOT THE PACKAGED GOO FROM NEW ORLEANS. AND IN THIS NEW AGE OF PANDEMICS AND HOLY WARS I WAS GLAD TO BE THERE. BOTTOMING OUT. LOOKING AT THE WORLD FROM UPSIDE DOWN.

I have visited Haiti several times since the overthrow of Baby Doc in 1986. The joy that followed that dechoukaj (uprooting) quickly gave way to explosions of anger and fear as a series of U.S.-backed generalissimos and their bagmen kept preempting the dreams of democracy. Finally at the thirteenth hour, after every single misery seemed to fall on Haiti: catastrophic deforestation, terminal political avarice, world-class duplicity, AIDS, crack—Prince Charming arrived on the scene. Jean-Bertrand Aristide, Catholic priest and activist in the street fights against Baby Doc was elected President by a landslide in Haiti’s first ever democratic election in December 1990.

Cynics in the hillside gingerbread mansions said it was the “E.T. factor”—tall and bony with a droopy left eye, “Titid” (as everyone called him by his Creole diminutive) was so homely you had to love him. But the streets were euphoric. All over town pre-Carnival masqueraders were wearing red kok kalite (fighting cock) masks. The cock is a symbol of Aristide’s political party. It had marked his place on the ballot. All his campaign posters and bibelots carried a picture of Titid juxtaposed to the kok kalite. There were so many flocks of rooster masks during Carnival celebrations that the streets of Port-au-Prince resembled a Kentucky Fried Chicken convention. And wherever the ersatz roosters passed, on walls and doors throughout town, red hearts were painted with these words of love “Titid, mon amour.” Haiti had a sweetheart.

Like all good fairy tales, there were utterly heinous monsters to confront the hero. Roger Lafontant, one of the Duvalier old-timers called “dinosaurs,” rallied the Tontons Macoutes for a preemptive coup against Titid. Mme. Ertha Pascal-Trouillot, the acting president, went on radio with unseemly haste to announce her surrender to the dinosaurs, and Titid went into hiding. Then the streets exploded. Furious mobs rooted out and sometimes murdered those suspected to be co-conspirators: the Macoute chiefs, the Vatican nuncio, and the loathed archbishop of Port-au-Prince, François Wolff Ligonde, a protege and in-law of Duvalier. The avenging moh thought they had Ligonde cornered in the old cathedral, a twohundred-year-old relic of slavery times recently restored through UNESCO funds. They burned it to the ground.

But the archbishop had already fled, probably to the presidential suite of the Hilton in Santo Domingo, the traditional first stop for exiled Haitian plutocrats. Lafontant was seized and arrested by army General Abraham, for once following the will of the people. So on February 6, Titid’s inauguration was celebrated in the rococo pink and cream Cathedral with the horrified elite, including Mme. Trouillot, looking on. Outside, ecstatic crowds pressed at the doors and hung from the concrete limbs of the crucifix shouting “ Yo sezi; Yo sezi\”—“They are shocked; They are shocked.”

Three days later Carnival began. Much of what Deren recorded forty-five years ago was still happening in the streets. The satined harlequins whipped the crossroads. The mulatto beauty queens distributed rose petals and glitter from their electrified floats. And the Creole troupes threaded about the floats transforming all the dread national soap opera into high—and very low—farce. The cast of characters has, of course, richened considerably since Deren’s time. A loony looking couple dressed in tattered tux and wedding gown stood under a satin umbrella while on-lookers jeered. It was an ersatz Baby Doc and Michèle Bennett, recelebrating the disastrous marriage that brought down the dictatorship. Close by a bald-headed Lafontant look-alike went marching with a group of blue-suited, redscarved Macoutes (or “Sans-Mamas,” as these “motherless” thugs are called) cradling cardboard uzis. Behind them the street marchers sang a song celebrating their improbable victory:

“The People are innocent,” Abraham said to the Sans-Mamas “You think you’re tough—But you’re not tough, And we won’t take no Coup d’Etat-O”

Titid was of course the hero of the Carnival. Bedraggled red fighting cocks hung from the standards of many marching bands. Often the cock was held over the grey pentard (guinea fowl), which has been the national symbol since the 1791 Revolution and was the favored fowl of the Duvaliers. A Carnival song scorned the last President, Mme. Trouillot, in this earthy language of the birds:

Ertha Pascal-Trouillot, Mama Caca, Look how you let the pentard, Get into the national coop.

On a wooden platform near the Champs de Mars, across from the Presidential Palace, a signboard had been painted with all the same characters from the national soap. Lafontant was tied up nude to a pole. His zozo (penis) was bound with cords. Trouillot, her coco (vagina) hugely magnified, was bent over and bare for the divebombing kok kalite. During Carnival, symbols aren’t subtle.

Counterposed to mock political dramas were more familiar monsters. At first I thought I was watching play-Arabs dressed in sheets and pancaked white faces. A parody of the Gulf War being played on CNN by the blancs ? But then I saw the familiar black top hat tugging at the rope that bound the hapless “Arabs”: Baron Samedi. And then I noticed the skeleton by his side carrying the coffin: son Guede. It was Le Troupe Zombie raucously mixing the ghouls of their folklore with the phantasms from Hollywood. Haitians are bemused by American fascination with zombies, who constitute only a small class of their mythological bakas (monsters). But if Americans want to buy these beliefs, Haitians don’t mind selling. Herard Simon, a Vodou strongman instrumental in helping Wade Davis buy the puffer fish zombie “medicine” revealed in his best selling The Serpent and the Rainbow, laughed as he told me, “We sold him the plans for the B-25, but we’ve kept the F1-11 secret.”

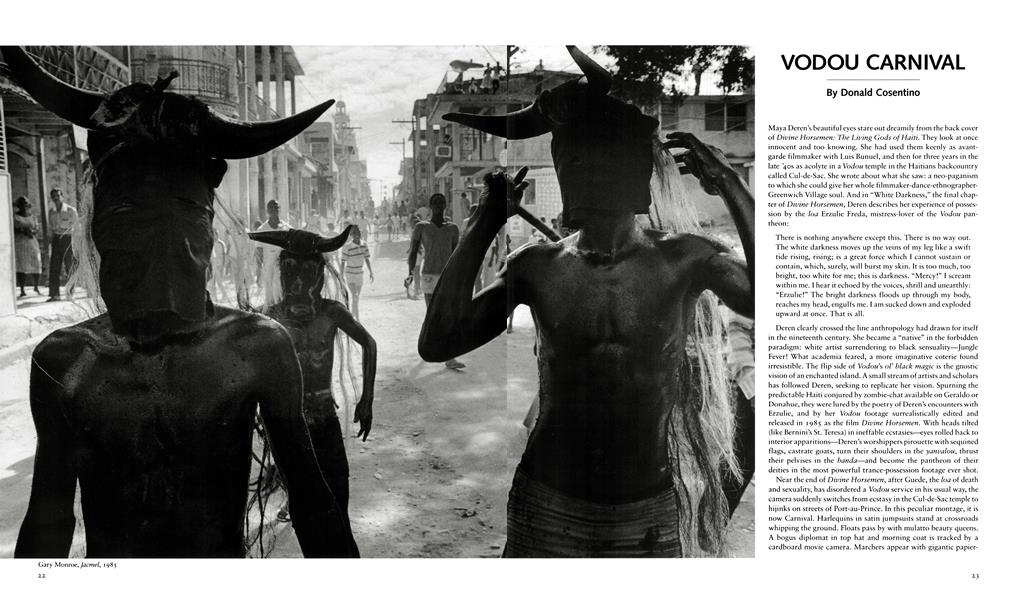

Following the zombies came the chaloskas: monsters with huge red lips and great buck teeth. They also wore eye masks, big hats, and Sgt. Pepper military regalia, and chased each other, and the laughing crowds, waving sticks. I first saw the chaloskas in Jonathan Demme’s brilliant film, Haiti Dreams of Democracy. He caught them performing in the 1987 Jacmel Carnival. They were wearing the same mad military gear, said to be in imitation of a nineteenth-century Haitian general. But the objects of their satire were clearly contemporary. Marching around in a half-assed goose step, the demented chaloskas sang, “There are no Macoutes in this troupe.” In the inverted logic of Carnival, their denial affirmed their identity. The honcho chaloska then pulled out a notebook and barked indictments to his peons, “You are accused of telling the truth...” And they brayed back through their big buck teeth, like a stand of donkeys, “ Wawawawawawawa.” And the general shouted, “You are accused of not kissing our ass !” And the peons responded, “ Wawawawawawawa.”

I recognized the interrogation. Maya Deren describes the Baron Samedi lining up his idiot Guede children and instructing them in human ways, “I love, you love, he loves—what does that make?. . . L’amooouuuurrrrL I too had seen the Guedes line up at one of Baby Doc’s favorite temples just a few weeks before the Macoutes aborted the national election by massacring voters in 1987. Holding his phallic cane like a baton, Baron Samedi led a troupe of Guedes through a martial display, every few steps pausing to execute a bump and grind. The brass band hired for the ceremony was playing “Jingle Bells.” The audience upstairs in the balcony kept chanting: Zozo, Zozo, Zozo.

Zozo . . . Zozo: the word means cock, and it means fuck, and everyone—men and women, sweaty faced and laughing hard—was shouting it in carnival. Just as every character—political, military, or celestial—stripped of his pretences is an avatar of Guede, so finally is every motive and every action reducable to zozo. Not I’amoooour ... or la vie ... or even l’honneur—only zozo. Guede may be foulmouthed, but he is the sworn enemy of euphemism. He lives beyond all ruses. He is master of the two absolutes: fucking and dying. Group after group danced down the Rue Capois, singing the grossest of his anti-love songs:

HAITIANS ARE BEMUSED BY AMERICAN FASCINATION WITH ZOMBIES, WHO CONSTITUTE ONLY A SMALL CLASS OF THEIR MYTHOLOGICAL MONSTERS. BUT IF AMERICANS WANT TO BUY THESE BELIEFS, HAITIANS DON'T MIND SELLING.

When you see a smart ass chick, Pick her up and throw her down, Pull down her pants, And give her zozo . . . wowowo!

One could wonder that women as well as men were shouting the misogynist lyrics. But Guede rides women as well as men. And among the Fon of Dahomey, whose descendants brought Vodou to Haiti, it is young women who strap the dildos on in masquerade. Zozo means cock no doubt, but what else does it signify? Is the zozo a flip off of established order? Of la misère? Or that irrepressible lingam that finds life in the death all around?

Since everything is reducible to Guede, and Guede cannot lie, he makes it possible to laugh even at the most terrible things. With Guede everything enters Carnival. Even AIDS (SIDA) the viral crossroads of both his domains. Thus the marchers in “Kontre SIDA” sang:

Oh Mama, lock up my dick, So I won’t fuck a trick, If I fuck, I’ll get AIDS Go and fuck your Mama’s crack!

Troupe “Kontre SIDA” marked their lyrics with the banda, Gliedes bump and grind. One young reveler waltzed around with a rubber dildo on his head. Another was waving a wooden zozo from a Guede shrine with a condom rolled over it.

The temptation of course was to say, “Oh, this is Haiti.” But it would be truer to say “this is Carnival.” Celebrated with as gross a humor as Rabelais’s jokes about syphillis (the AIDS of the Renaissance) in Gargantua. This is the real festival of reversals, not the packaged goo from New Orleans. And in this new age of pandemics and holy wars I was glad to be there. Bottoming out. Looking at the world from upside down.

I watched the last hours of Mardi Gras on TV at the Olaffson Hotel bar. I had been roughed up on the streets, had my pocket picked, been shoved away from the balcony of the Holiday Inn where the journalists and tourists were shooting film. So I went back and watched the tube with Maurice the bartender. And I think I saw what Maya Deren saw. The bourgeois floats sailing by with their mulatto crews, oblivious to the black, saucy street ensembles swirling in and out about them. All those Creoles moving to the same zozo songs I heard at a Guede ceremony just before the ’87 massacre. Carnival and Vodou ceremony both for Guede. Even explicitly so. The TV screen panning the crowds in front of the Holiday Inn suddenly split, and the lead singer of Boucan Guinee appeared in the white face of Guede Nimbo, most dapper of Baron Samedi’s children. He sang what was the theme song of the Carnival, “Pale . . . Pale" (You Talk and Talk):

You talk and talk and talk and talk; But when you finish talking, When you stop, I’m still here. And from the ground, I’ll come out. And from the ground, I’ll walk around . . .

Boucan’s image, the corpse of Guede, merged with last frames of Divine Horsemen. Guede then and now and everywhere. In this poorest country in the New World, misery becomes a trope for three days. The dinosaurs and Macoutes, the zombies and the chaloskas are defanged by Guede and a chorus of the laughing people. And finally, at 5 A.M. on Ash Wednesday, the vanities of Carnival are thrown into a giant bonfire in front of City Hall. Ashes for Guede ... to start again.

THE GIFT of starlight and fire touching your face stinging it raw the bathing scouring with broken herbs burning liquid flames stinging against your eyes your hands and chest the soles of your feet

PAUL UHRY NEWMAN

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

A Place Called Haiti

Winter 1992 By Amy Wilentz -

Postcards From History

Winter 1992 By Mark Danner -

Serving The Spirits Across Two Seas: Vodou Culture In New York And Haiti

Winter 1992 By Elizabeth Mcalister -

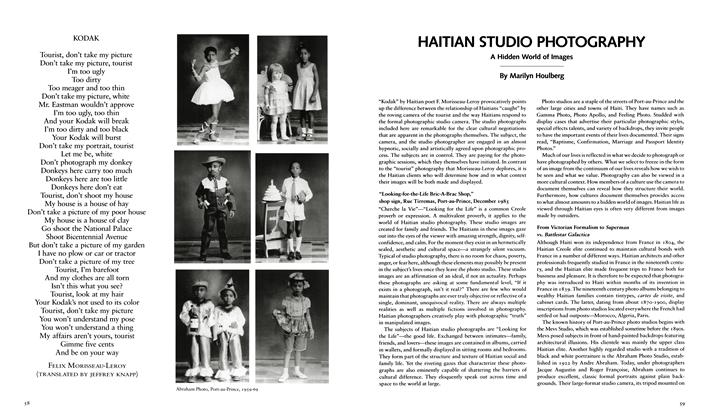

Haitian Studio Photography

Winter 1992 By Marilyn Houlberg -

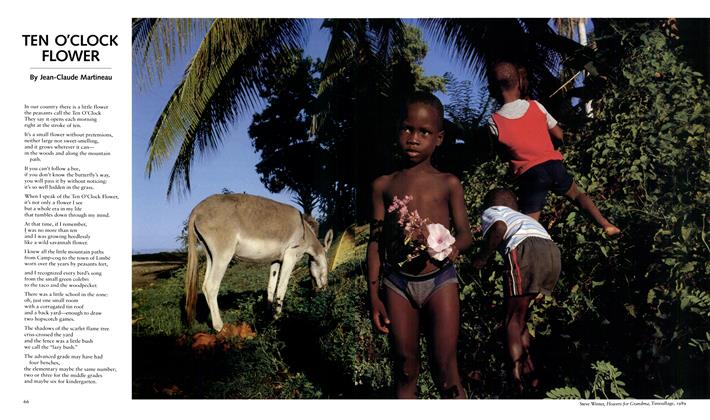

Ten O'clock Flower

Winter 1992 By Jean-Claude Martineau -

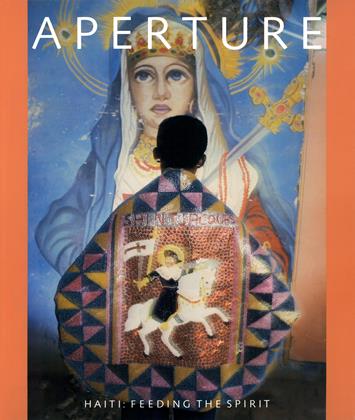

Haiti: Feeding The Spirit

Winter 1992 By The Editor