Prodigal Stories: AIDS and Family

Tom Kalin

The story, reproduced endlessly on television, in newspapers, and in magazines, has become painfully familiar. Perhaps the fable inflicted its moral punchline upon you during youthful religious training; like most of culture's stories, this one is delivered to us from history and adapted for contemporary use: the parable of the Prodigal Son. The yarn unravels like this: boy is born and raised in the pastoral safe haven of family. Boy’s eye, lured by the urban bauble’s glitter, propels his body from home into the wanton spending of his youth and inheritance. Boy becomes debauched, stealing food from pigs. Boy, sick and consumed with self-pity, returns home to family, forgiveness and healing.

The depiction of gay men with AIDS in mainstream media continues to be obscured by a swamp of such vindictive fictions. The combined effect of the images and texts that constitute our collective mythologies (from folk tales to magazine advertisements, novels to newspaper editorials, photography periodicals to television programs) produces complex cultural arguments from which we are permitted to decipher events and identities. Reading across these texts reveals the controlled deployment of images and words in constructing “public opinion.” Deliberately managed representations, such as the consistent use of the heterosexual family to evaluate the lives of (both gay and straight) people with AIDS (PWAs), reemphasize existing homophobic, sexist and racist discourses. Admittedly, I am overly sensitive and cranky regarding these issues; as the youngest of a Catholic family of eleven children, family signifies both alienating abstraction and difficult reality.

As I juggle these words, the television (always on when I write: part antagonist, part ambience) blares that Ryan White—“the boy who taught us about AIDS”—has died in Kokomo, Indiana. Ironically, Ryan White the person was mostly obscured by the media fabrication of Ryan White the “innocent AIDS victim.” White became an emblem of blamelessness and compassion, a calm, white, middle-class center to the untidy realities of a crisis which affects so many people outside of the nuclear family’s closed circuit. Dominant forms of media persist in constructing a nonexistent “general population,” the rhetorical device critic Jan Zita Grover has described as “the repository of everything you wish to claim for yourself and deny to others.” This immaculate brigade has continued to shrink since the early days of the AIDS epidemic. Originally including all heterosexuals, the “general public” diminished along race and class lines as it became clear that many AfricanAmerican and Latino heterosexuals were HIV-positive, or living with AIDS. I knew immediately, when I read the phrase, I was not included.

The scripted narratives that inform readings of the AIDS epidemic contain a hierarchy of blame, a cast of characters that includes “guilty” victims: gay men, IV-drug-users, African and Haitian heterosexuals; and “innocent” ones: hemophiliacs, pediatric AIDS cases, and people infected via transfusion. Even depictions that attempt to counteract prejudice and discrimination (for instance the 1985 television special An Early Frost) unfortunately persist in depicting gay sexuality as guilt-ridden and inherently deceptive. Not content to let the gay PWA remain with his lover, An Early Frost brings its prodigal son home to his straight family to die. The real star of An Early Frost, however, is not the upwardly mobile lawyer with AIDS, played by Aidan Quinn, nor his mother (Gena Rowlands). The protagonist—our main point of identification—is the father (Ben Gazzara). His struggle to tolerate the double disclosure of his son’s sexuality and AIDS diagnosis, and to regain the symbolic law of the father, acts as the motor of this movie, a familiar special-of-the-week struggle between sons and dads that is heightened by familial shame of the closet.

NO ROOM FOR ERROR

AIDS testing should leave no room for false positives.

Advertisement for SmithKline Biological Laboratories (detail)

This positioning vis-à-vis the nuclear family virtually erases the fact that most gay men and lesbians have lives that integrate alternative formulations of the family, that, contrary to Hollywood’s popular myth, most lesbians and gay men do not lead desperate, lonely lives, alone with their uncontrollable, predatory promiscuity. Ultimately, An Early Frost presented a fairly balanced and progressive (for mainstream television standards) attempt to “put a face on AIDS.” Unfortunately, this peculiar notion of granting identity to those of us who are already people (and then some) almost always plays allegedly conflicting ethical systems against one another. The recent rebroadcast of An Early Frost also served to reinscribe misinformation in popular imagination; the only heterosexual man with AIDS (white), claims that he “got AIDS” from a hooker. People are infected with HIV (not the AIDS virus), an infection that may eventually lead to the series of opportunistic infections called AIDS. Conveniently scapegoated sex workers have been statistically proven to have comparatively low rates of HIV infection due to consistent use of condoms.

The recent American Playhouse special Andre's Mother, starring archetypes Sada Thompson as the mother of a person with AIDS and Richard Thomas as the PWA’s lover, resurrects the nuclear family as a framing device. In this slice-of-life the writers acknowledge more directly the complex tensions that arise around the collision between chosen and biological family. Andre's Mother, nonetheless, revolves Rashomon-style around an absent person with AIDS; our belief is suspended as the action takes implausible turns to ensure that the son with AIDS remains offstage, invisible. People with AIDS are often consistently and vindictively erased or, equally alienating, pictured alone, without community or context, seen as dependent and helpless.

The portraits of people with AIDS by both Rosalind Solomon and Nicholas Nixon have rightfully produced controversy. Both William Olander, former curator of the New Museum of Contemporary Art (who died of AIDS in March, 1989) and Douglas Crimp, critic and editor of October magazine, have spoken articulately and passionately about the works of these two photographers. Though aesthetically and technically divergent, Solomon’s and Nixon’s works share a persistent vision of the isolated subject, showing over and over again images of people with AIDS, alienated from society and facing death alone. Almost without exception, these subjects are set against the backdrop of their reproachful, grieving families, far from friends and lovers. Describing Solomon’s exhibition at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery, Olander states “For the viewer . . . there is little to know other than their illness.” Little, that is, unless you go on to read curator Thomas Sokolowski’s catalogue essay, which lends Solomon’s images the weight of history. Fie deciphers the images as if “they were contrived as parodies of the art historian’s formal description and source mongering” (Douglas Crimp). In an interpretation similar to that of writer Robert Atkins (Aperture 114), Sokolowski manages to disengage completely with the specific material reality of the subjects, and instead reads them like so many canvases by Manet. (The image numbered 20—all the works, incidentally, were of unnamed people—becomes, for Sokolowski, not a picture of someone sick with AIDS-related infections, but, rather, an intricate and historically referenced Venus.) AIDS is not a Great Theme, ripe for the depiction of suffering, sympathy and transcendent universals. AIDS is a social, cultural, medical and political crisis already overburdened with damaging myths. People living with HIV and AIDS have responded by taking on the power to control their own representations, choosing to be speaking subjects rather than fodder for a practice of an insipid, vague humanism.

Solomon’s photograph titled Barbara Bruce, Medical Doctor, (Attacked by a Shark in 1963), 1988, is a curious selection for another recent exhibition dealing with AIDS: “The Indomitable Spirit” at the International Center of Photography Midtown. Curated by Marvin Heiferman, this collection of photographs is intended to “celebrate human strength, compassion, and endurance in the face of challenge and adversity.” Solomon’s photograph, contextualized here by her (absent) body of AIDS portraits, confirms my suspicion that for her, people with AIDS are but another series of models in a long parade of documentary oddities. Recalling Diane Arbus’s deadpan shock tactics, Solomon’s image conveys, according to its accompanying wall text, “resiliency and fierce dedication.” Heiferman’s wall labels, which exert a gentle-yet-firm forced reading throughout the show, serve as a textual docent tour, tenuously uniting a wildly divergent exhibition into a project of ostensibly “positive” representation.

Faced with the inadequacies of conventional photographic practice and mainstream media to challenge stereotypes of PWAs (both within and outside of the family), many artists, activists and people with AIDS have produced compelling counterrepresentations. These projects cut across theater, photography, painting, independent film/video, and broadcast documentary and include a diversity of approaches: from the People with AIDS Theater Workshop to GMHC’s (Gay Men’s Health Crisis) weekly cable show Living with AIDS; from David Wojnarowicz’s painting, photography, film and writing to Amber Hollibaugh’s documentary The Second Epidemic, 1987-88, for the New York City Commission on Human Rights’ AIDS Discrimination Division; from Carl George’s Super-8 film DHPG Mon Amour, 1989, or Stashu Kybartas’s 1987 video Danny, to Patricia Benoit’s and the Haitian Women’s Program’s 1988 video, Se Met Ko. Spanning both aesthetic and idiosyncratic testament and didactic prevention information, these and other works consistently challenge presumptions of audience, family, and cultural context. Eroding the rhetoric of the “general public,” such images recognize an expanded audience of spectators.

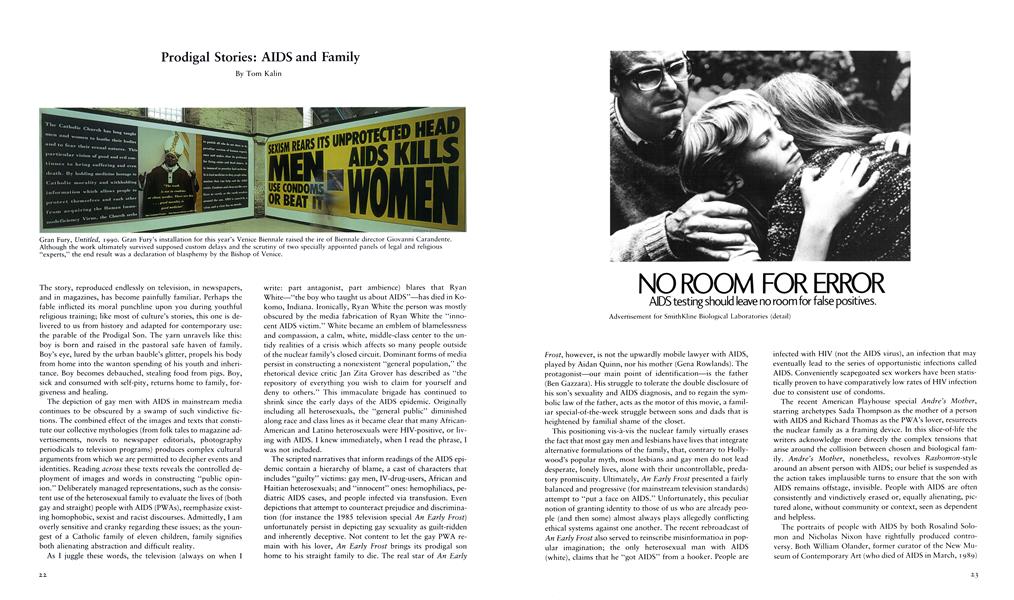

Public billboard projects by the AIDS activist collective Gran Fury (of which I am a member), and Felix Gonzalez-Torres (a member of the artists’ collective Group Material), attempt to address a broad audience, inserting into the space of commercial manipulation a reconsideration of forms of public information. Gonzalez-Torres’s untitled billboard, which ran last year on New York’s Sheridan Square (directly facing the site of the Stonewall riots, often cited as the birth of “gay liberation”), contains a blank, black field with two bands of text reading, simply: “People With AIDS Coalition 1985 Police Harassment 1969 Oscar Wilde 1895 Supreme Court 1986 Harvey Milk 1977 March on Washington 1987 Stonewall Rebellion 1969.”

People living with HIV and AIDS have responded by taking on the power to control their own representations, choosing to be speaking subjects rather than fodder for a practice of an insipid, vague humanism.

Insisting upon a reconsideration of the formation of history, societal and cultural control over the body, and the inadequacies of the photographic field of vision to sufficiently convey the erasures of official history, Gonzalez-Torres uses language and a blank horizonless field to comment on the bankruptcy of the documentary image.

Gran Fury’s billboard Welcome to America, which appeared in both Soho and Harlem as part of the Whitney Museum’s “Image World” exhibition, pictures a giant, smiling AfricanAmerican baby and the text: “Welcome to America the only industrialized country besides South Africa without national health care.” The failure of the American system of health care and our continued lack of a comprehensive program of socialized medicine have been profoundly complicated by the crises of health care, homelessness, AIDS and the continued impending threat to women’s rights to control their bodies. All of these wars—the struggle over AIDS funding, treatment and policy, or the battle over reproductive rights, for instance, vividly reveal the fact that our ability to control our lives and our bodies is governed by an elaborate and fragile series of permissions and withholdings.

The durability of prodigal son fables and the power of institutions such as the Catholic church (which pathologically glorifies family and completely disavows tiny little facts such as sex outside marriage, the realities of rape, or that condoms and clean needles save lives) necessitate projects of counterrepresentation. The overlaps between the politics of reproductive rights and AIDS suggest a vulnerable spot in the foundations of such ideology, shared sites of contestation where effective coalitions defy allegedly irreconcilable differences. Poisonous fairy tales and disappearing acts are being challenged by both direct action and representations, insisting the war isn’t over for anyone until it’s over for everyone. □

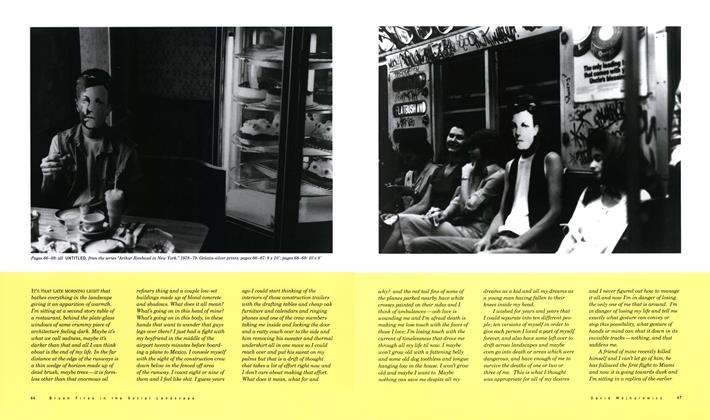

After eight years of silence from Ronald Reagan concerning the AIDS epidemic, we as a society had to endure the media spectacle surrounding the polyps found in the president’s colon during a routine medical examination. We were treated to endless television programs, newspaper photographs, and diagrams that placed the presidential colon in our streets and in our homes. The murderous silence of Reagan has been extended by the Bush administration aside from a couple of slimly crafted sound-bites and photo-opportunities. What the AIDS epidemic makes clear, apart from a national disease called: FEAR OF DIVERSITY (the symptoms of which include sweaty palms, violent outbursts, burning down homes, passing certain legislation, invading foreign countries and ultimately the legal murder and expendability of the Other) is that the real people in power in this landmass we call America are the people who control the means of image reproduction and information dissemination. The owners of newspapers and the owners of television stations are guilty of a selective dissemination of information that pertains to our bodies, information that, if completely available, would allow each and every one of us a chance to make informed decisions that could safeguard our bodies and sexual activities during the AIDS crisis.

A camera in hand can help people understand that when they buy a newspaper, they are being bought. A camera in hand can create a rich historical record of our bodies, our lives, and the environment our bodies move about in that contests the historical record formed and implemented by rich white owners of mass media. A camera in hand can keep our bodies and our psychic and physical needs visible in a country where those needs are being legislated into invisibility more and more. Photographs can save lives by creating informational vehicles from which all of us can draw in order to make informed decisions affecting the health and well-being of our bodies and our sense of identity in a country that trades heavily on the illusion of the One Tribe Nation.

A camera in hand can create a socially divine moment in late twentieth-century style and methods of telecommunications. A camera in hand can produce images of authenticity that break down the walls of state-sanctioned ignorance in the forms of mass media/mass hypnosis and stir people to do what is considered taboo and that is to speak. Breaking silence about needs or experiences can break the chains of the code of silence. Describing the once indescribable can dismantle the power of taboo. Speaking about the once unspeakable can make the invisible familiar if repeated often enough in loud and clear tones and pictures. To speak of ourselves in a climate and country that considers us, our bodies, and our thoughts taboo is to shake the boundaries of the illusion of the One Tribe Nation. To keep silent even when our individual existence contradicts the illusion of the One Tribe Nation is to lose our identities and possibly our lives. Bottom line, if people don't say what they believe, those ideas and feelings get lost. If this is the case often enough, then those ideas and feelings never return.

History is created by and preserved for rich white straight people. Views of the human body have been informed by this version of history to the point at which the functions of the body, such as sexuality, have been reduced to a generic set of symbols that remain at odds with what we privately embody. It is no surprise that sexuality as represented in media always tends to leave the taste of static or printer's ink on the tongue, whereas the human body explored with a camera in the hands of a sensitive individual can leave the taste of sweat or blood. In the hands of the latter, a camera-generated image of the human body can be encoded with a vague memory that taps deep into a viewer's private history.

One of the more powerful forces that engages in activities designed to distract us from gazing at our own bodies is organized religion. Cult organizations rallying around symbols of sacredness have always found it easy to be vicious and murderous. They realize the power inherent in pictures. St. Patrick's Cathedral is currently installing a press section with a raised platform for camera crews. A spokesman for the cathedral stated in the Daily News: “We have planned it for some time as a way of balancing the press’ and the worshipers’ needs. ...” The Archdiocese echoes the Vatican in its position that it is a more terrible thing to use a condom than it is to contract AIDS. Pat Robertson and the Christian Broadcasting Network (CBN) have waged insidious propaganda campaigns on behalf of extreme right wing interests (see Sara Diamond’s Spiritual Warfare: The Politics of the Christian Right,). Robertson as of late has been using the 700 Club to help disseminate his and other politicians’ false interpretations of NEA-funded images and performances in order to either dismantle public funding of the arts or to influence Congress to adopt homophobic or anti-body legislation as guidelines for the NEA.

In the last year, singular images such as photographs of the human body or body fluids have gained a power they haven’t had since the invention of television. Until recently, an artwork or photograph has had little reverberation in a society that depends on telecommunications for most of its information and response. So is it the photograph of a cheap plastic crucifix immersed in a natural body fluid that suddenly has so much reverberation and power in contemporary American society, or is it the men in Congress, with access to networks such as CBN that have imbued this image with power? The work in question is “dangerous” insofar as it acts as a magnet to attract people whose spirituality has been alienated by organized religion. Its power lies in the representation of doubt in an age where the separation of church and state is nonexistent, where people have become confused to an extent that they believe that God and government are similar functioning bodies. Images can he used as tools of alert, or tools of organization. A photographic image can be a disruption of previously unchallenged power.

DAVID WOJNAROWICZ

Editor's note: In June 1990, David Wojnarowicz sued Reverend Donald E. Wildmon, who misrepresented and distorted the artist's work by taking certain carefully selected fragments from the photographs comprising Wojnarowicz's “Sex Series," and reproducing and circulating them in his American Family Association publication—the implication being that the images (presented completely out of context) were pornographic. The June trial initially resulted in the judge issuing a temporary injunction blocking the circulation of Wildmon's pamphlet. A decision was reached regarding Wojnarowicz's suit against Wildmon in August 1990. Wildmon was asked to send a “corrective letter" to his subscribers and Wojnarowicz was awarded one dollar. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Photography, Pornography And Sexual Politics

Fall 1990 By Carole S. Vance -

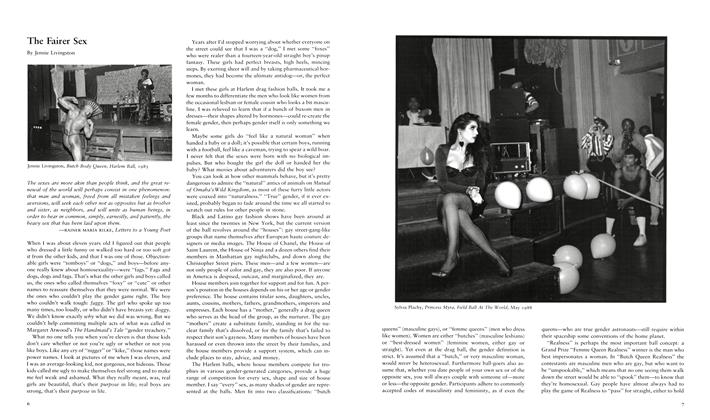

The Fairer Sex

Fall 1990 By Jennie Livingston -

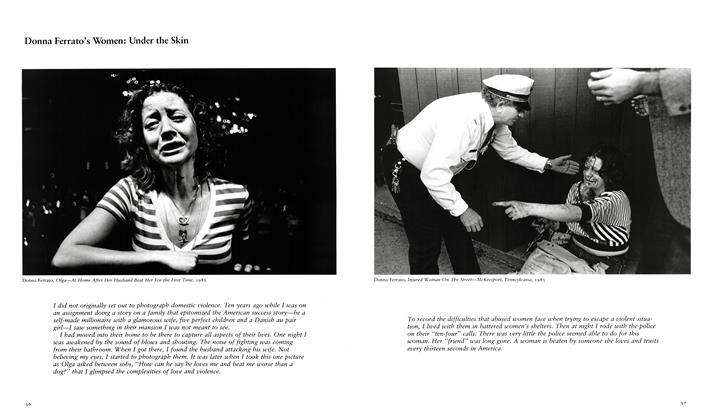

Donna Ferrato's Women: Under The Skin

Fall 1990 -

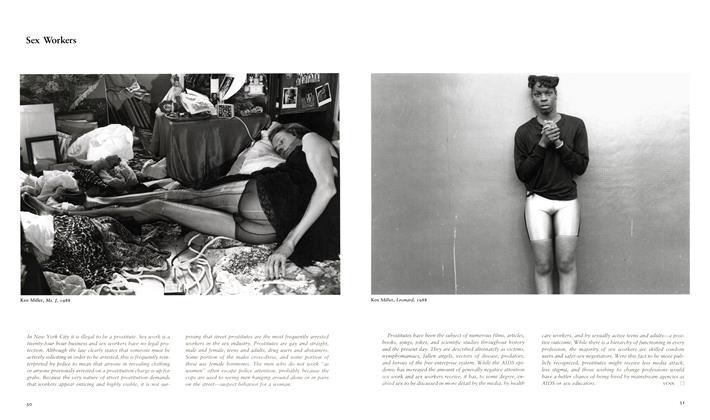

Sex Workers

Fall 1990 By Synn -

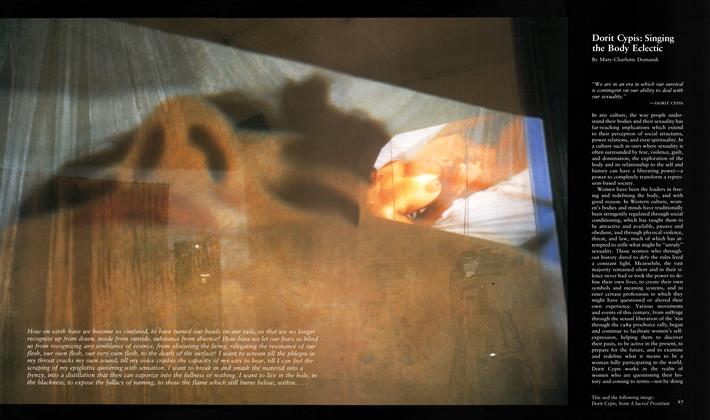

Dorit Cypis: Singing The Body Eclectic

Fall 1990 By Mary-Charlotte Domandi -

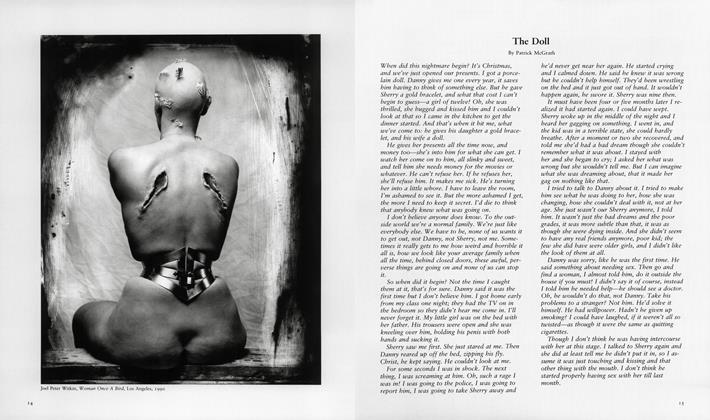

The Doll

Fall 1990 By Patrick Mcgrath