Cezanne’s Apples and the Photo League

Louis Stettner

The Photo League, a volunteer organization of amateur and professional photographers located in New York City from 1936 to 1951, numbered among its members, guest speakers, and teachers the most illustrious photographers in America in the 1930s and 1940s. Born from a belief in social change and the ability of the image to affect it, the League eventually fell victim to the histrionic political climate of the 1930s and was forced to disband. Its members left behind a legacy of documentary photography that remains one of the most impressive in this country. In this memoir, Stettner, a long-time member of the League, shares his sense of the history of that time.

THE EDITORS

TO THE ESTHETES

Dust from your eyes makes barren the landscapes on your walls all done by famous hands and bought at a notorious cost for your private desecration. Never, you shall never be as common with creation as the present you shudder from. Cezanne in him found fellow feeling; not in you. ISIDOR SCHNEIDER Mainstream, Spring, 1947

One cannot help but be intrigued, even fascinated, by the contradictory fate history has meted out to the Photo League. Perhaps no other artists’ organization in America has been so condemned by government officials, and yet so enthusiastically explored by those with a passion for photography as fine art. Hardly a year goes by without the photographers of the Photo League made the subject of an essay, an article, a learned thesis, or an exhibition. While some new facts are unearthed, and some valuable insights recorded, the main essence of the Photo League seems to have been blurred or distorted. History has been rewritten into something the Photo League simply never was.

Born out of the rich and varied political ferment of the twenties and early thirties, the League was, above all, the first progressive, left-wing photography organization in the United States. Its origins go back even earlier, to the Pen and Hammer Club, organized around socialist concepts predicating a unity between artist-intellectuals (mostly writers) and working people. John Reed, its most illustrious member, was a committed journalist, who joined Pancho Villa in the Mexican Revolution before going to Russia in 1917 to write the monumental Ten Days that Shook the World. In 1928, motion-picture and still photographers formed the Film and Photo League, which, after the departure of the motion picture members in 1936, became the Photo League. The Photo League was organized and run by the photographers themselves. Dues were relatively small, and if one could not afford to pay, one could earn membership by sitting at the desk during exhibitions or by helping in the darkroom. It was not a catch-all organization that stayed clear of troublesome policies and goals in order to have as large a membership as possible. Those who joined knew they were sharing a common orientation and direction in their art, a documentary approach that was progressively left and people-oriented. As an organization, it had two important goals: first, through activities, exhibitions, school lectures and publication of Photo Notes, the development and encouragement of photography as a fine art; second, the use of photography as a tool to help working people in their struggles, and to document and interpret their daily lives.

For radical political ideas to have an important influence on artists and movements is not new in art history: Pablo Picasso was deeply moved by the anarchist and socialist movements that flourished in Barcelona at the turn of the century, and during the Spanish Civil War harbored Republican refugees in his studio. His famous Guernica, produced for the Spanish Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair in 1930, testifies to that belief. Robert Henri, an ardent socialist and an influential art teacher, first in Philadelphia and later at the Art Students League in New York, became the mentor of John Sloan, Edward Hopper, and the so-called “Ash Can” group of painters. Instead of depicting prosperous merchants posing in front of sentimental, carmelized sunsets, they took as their subject matter the working people of New York: bathers at Coney Island, office secretaries partying under the Third Avenue El, children playing in back alleys. The Ash Can artists were appreciated by several important photographers experimenting with hand-held cameras: Alfred Stieglitz and members of his group, as well as Paul Strand doing his first candid camera series in New York streets. Later, the Ash Can school served as valuable forerunners for the Photo League photographers working on their numerous street projects. It may come as a surprise to some to learn that the street photography, so commonplace today, was born of a political concept.

Aside from its political antecedents in art, myriad factors went into the formation and growth of the Photo League. During most of its formative years, America was reeling from the devastation of the Great Depression: hunger, bread lines, evictions, and the selling of apples and valuables on the streets were in evidence everywhere. During the depression, artists joined the people struggling on many different fronts. The Works Progress Administration nurtured the photographers Dorothea Lange, Minor White, and others, and such painters as Ben Shahn, Thomas Hart Benton and Jackson Pollock (who, they say, was inspired by paint drippings on the floor while making signs for demonstrations). But this work for artists was not offered to them on a platter: weekly wages for artists were won after picketing and protest parades of as many as 5,000 painters, lasting weeks, won sympathy for their cause. Other battles for unemployment insurance, unionization, and minimum wages improved working conditions nationwide. Later, when the American people mobilized the necessary strength and heroism to help destroy Fascism, the progressive left played an important role by helping them organize.

The Photo League was not just a reaction to the Great Depression; it also grew out of a tradition in American photography represented by Stieglitz, Hine, and Strand. Lewis Hine and Paul Strand were frequent visitors to the League (I remember helping to make prints from a Hine negative for a fundraising event). Since quality printmaking was emphasized, there were serious debates concerning the merits of gold-toning, ferrocyanide, and other materials. An exhibit of Strand’s Mexico portfolio, superbly printed in heliogravure, and varnished to give luminosity to the shadows, encouraged League members to try and get emotional values in their prints by means of tonalities, texture, and great detail. It was Strand’s contention, which he very clearly articulated, that all visual media obey the same esthetic laws, so that one could compare the qualities of blacks in an etching with those of a silver print. The first New York exhibition of Edward Weston’s 4x5 California portraits also encouraged fine printmaking among the Photo League photographers.

The League had an international outlook, exhibiting photographers from all over the world. Manuel Alvarez Bravo from Mexico and others had their first New York shows at the Photo League. After the war, I went to France and sent back the first collection of contemporary French photographers to be exhibited in the States: Brassai, Doisneau, Izis, Boubat, and others. Brassai once told me that it was the success of this show and its publication in the international U.S. Camera that led to the subsequent exhibition of French photographers at the Museum of Modern Art.

The Photo League was an invaluable meeting place and clearing house for ideas about creative photography. One can hardly think of a significant photographer of the time who did not exhibit, drop by, give or attend a lecture, or sit in on one of Sid Grossman’s classes at the Photo League. Among the photographers associated with the League in this way were Lisette Model, Weegee (who received his first show at the League), Robert Frank, Eugene Smith, Berenice Abbott, Henri CartierBresson, Ansel Adams, and Robert Capa. Equally important were the regular members: Sol Libsohn, Lisette Model, Walter Rosenblum, Elizabeth Timberman, Morris Engel, Elizabeth McClausland, Jerome Liebling, Morris Huberland, Ruth Orkin, Dan Weiner, and many others who made important contributions to the League.

The Photo League was the only place on the East Coast where fine-art photography was dealt with on a high level. There were camera clubs around, but they mostly comprised pictorialists doing quaint images printed on a variety of exotic papers (gum carbro, for example). There was a sameness in the work of those photographers that made it hard to distinguish differences in personality or vision. Since at the time photography was not even a respectable course of study in most colleges and universities, the Photo League provided a valuable bridge between past and future, carrying forward and developing an important current in American photography.

One cannot speak of the tradition championed by the Photo League without underscoring the work of Paul Strand. Just as Michelangelo left a deep imprint on practically every artist of his generation, so did Paul Strand influence the Photo League in theoretical and practical approach. In social concern, esthetics (an almost religious respect for fine printing) and attitude, Photo Leaguers wholeheartedly embraced Strand as their mentor and guide. Indeed, his influence was so overwhelming at times that lesser talents ended up by imitating his style rather than producing original works of their own.

Studying with Lewis Hine, Strand became one of the first photographers to break with the romantics around him and embrace social realism. Responding to a question I posed to him in a 1972 interview, Strand commented:

In the work of Stieglitz, and even Steichen, and Coburn and the others, there ivas always a kind of romanticism, whereas I was a realist . . . Mind you, I’m not saying this in a way to put down the Photo Secession—a very important group which I now strenuously defend because their value, their historical contribution has been so lost sight of these days. Yes, I am a realist artist, not a romantic one. But I am not isolated. True, I was doing those things way back in 1915— 16. You see the realistic development of the use of the camera going on and developing in the Farm Security Administration, in the work of Ben Shahn, as a photographer as well as a painter—his painting of Sacco and Vanzetti and the photos he took for Stryker in the FSA—in Dorthea Lange, and others. There was a whole group of people working in the same vein. I was only twelve years ahead of them, that’s all. However, I was interested in solving certain problems that never interested them. Maybe Ben was the only one of them traveling the same road as myself.

It was also important to The Photo League that Strand was a pioneer in street photography. Starting around 1912, he was the first to work candidly in the street when cameras were cumbersome, and film speeds slow. He remembered:

I used to wander around New York City, all over it; Bowery, Wall Street, uptown, the viaduct that leads from Grant’s Tomb. I could see everything, but to be able to do something with it, that’s another matter! I was not ready until 1913. Before that I was just groping, trying to feel my way. I would ask myself, what do Picasso and those other painters mean? Why do they do it that way? Why?

I would say three important roads opened up for me. They helped me find my way in the morass of very interesting happenings which came to a head in the big Armory Show of 1913. My work grew out of a response to first trying to understand the new developments in painting; grew out of a very clear desire to solve a problem. How do you photograph people in the streets without their being aware of it? Do you know of anybody who did it before? I don’t.

Strand never conceived of photography (no matter how great his respect for esthetic craftsmanship) as separate from life and its social problems. Here we come to one of the most important, overlooked contradictions in creative photography. Camera, film and development follow objective scientific laws, but the final picture is essentially a subjective interpretation of reality. The photograph inevitably tells us as much about the photographer as the subject matter. We are what and how we photograph. A photographer who sees his or her photography as separate from and out of the mainstream of human activity runs the danger of falling into serious estrangement, from which it is difficult to create and produce. Not only did Strand see himself vitally concerned, but I believe it is to his great credit as a human being that he fearlessly fought (often with his photographic skills) the political evils of his time. He courageously entered the area of struggle on the side of the progressive forces.

From Photo Notes, January, 1948:

On December 4, 1947, the special board appointed by president Truman to examine the loyalty of federal government employees released to the press a list of “totalitarian, fascist, communist or subversive” groups prepared for its guidance by attorney general Tom C. Clark. On this blacklist, together with the communist party, the Ku Klux Klan, and such organizations as the civil rights congress, the joint antifascist refugee committee, and the veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, the Photo League was astounded to find its own name.

On December 16, a special meeting of league members to discuss what action the league should take was held at the Hotel Diplomat, and Paul Strand was the keynote speaker. In a passionate address he championed the role of the artist as an advocate for the individual’s voice in society:

.... To silence you, intimidate you, make you think before you speak or not dare to think your own thoughts, but to go along with something that people are not willing to go along with—these are the objectives of the reactionary forces existing in our country today. My feeling is that Americans, if they know the truth, have good instincts of fair play, and don’t want to become cannon fodder in an atomic war.

The methods of reactionaries are not new. The chief one is red-baiting. It is an old trick and Hitler used it effectively. It divides and confuses people, and gets them looking for the real culprits everywhere except in the place where they are. Senator Glen Taylor recently said: “The Nazis had everyone looking under the bed for communists, and when they got up from their knees, they were looking right straight into the ovens of Buchenwald.”

That is why we here tonight have to stand up to this thing. No use in trying to run away and be afraid and say, “Please, I am a good boy.” It wont do any good. We have been picked out because we are articulate people. The artist himself, if he is really an artist, has to tell the truth as he sees it. He cant help himself. As soon as he stops telling the truth, he ceases to be an artist. The reactionary forces are quite aware that we, the photographers, the painters, radio commentators, film writers who have a craft and medium by which to express ourselves, will tell the truth, once we see it. And artists have a good sense of the truth. And that is why they want to silence us.

There is an old quotation from Nazi ideology: “When I hear the word ‘Culture,’ I reach for my gun.” Well, they did. But we should not think that they did that because they hated culture. People like Goering were art collectors. They stole all the painting they could get hold of in Europe. They tried to buy Picasso, Matisse. Their propaganda, calling such artists decadent, was only for home consumption. They pulled their guns, because they were afraid of the artists, couldn’t get them to toe the mark, crawl, and heil Hitler in their work. Well, the time has come for us in the Photo Teague to realize that something like that is happening in America today. The reactionaries are reaching for their guns. . . .

Between 1936 and 1945, an early supporter of Paul Strand and one of the great leaders of photography, Alfred Stieglitz, working at An American Place, was no more than forty street blocks from the Photo League, but never became even slightly involved with them. Nevertheless, Stieglitz's early pre-Worid War I work was close in spirit to the Photo League. There was his pioneer photography with the hand-held camera; he used such equipment because he wanted to work outdoors in the streets of New York, photographing what was immediately around him. Anyone seriously working with a miniature camera today is indebted to him.

“The Steerage” in 1907, which remains his masterpiece, was a key breakthrough in the history of photography. Perhaps the first photograph in which the visual structure is a direct, original expression of the photographer’s feelings about and interpretation of the subject matter, it is, to put it almost into a formula, a photograph in which form flows from content. The revolutionary implications of his approach can best be appreciated by looking through photography magazines of the period: pages and pages of formal, academic compositions, imposed on trite, banal subject matter.

Let us not forget what Stieglitz was photographing when he took “The Steerage.” Dressed in spats and white collar, a firstclass passenger pointing his huge Graflex into the grimy and dirty hold, Stieglitz saw those “masses of downtrod humanity” eating and sleeping as closely together as cattle. It is a deeply human photograph and indicative of the profound contradiction in Stieglitz which tormented him the rest of his life.

Looking back at his career, he seemed to embody two major photographic identities in his life. The first was from the preWorld War I era. During that time he was the active, outgoing person, photographing everywhere, publishing and exhibiting the works of other photographers—in a spirit very similar to that of the Photo League, had it existed then! The second Stieglitz, after World War I, turned away from the world, becoming ever more inward and introspective. He restricted his photography during the remaining thirty years of his life to views from his gallery window, to the immediate vicinity of his summer home in Lake George (also a cloud series), and to portraits of his artist friends (all very personal, significant photographs). His inward retreat can only be understood by appreciating the brutual shock given him by the World War I holocaust.

Prior to the slaughter of 5,000,000 people, Stieglitz’s ideological position was that artists were not just important, but that somehow they could quite effectively change the world. Then there was the war, the Great Depression, and finally, World War II. Stieglitz’s reaction was not to pitch in to the struggle and join the progressive forces (unlike Paul Strand, who spent ten years fighting fascism), but to create in An American Place a spiritual haven for his painters and a few photographers, as well as a spiritual force. Oddly, his dedication to creative art and wholehearted belief in its possibilities influenced Paul Strand and the rest of the Photo League.

It must be remembered that around the turn of the century painting and photography were often used to convey a sentimental vision of the world, not as means to find great spiritual significance in reality. This was especially true with photographs employing soft-focus techniques, in the footsteps of Impressionist painting. It is regrettable that Stieglitz and the Photo League never could get together, since right to the very end they had more in common than they realized. Both looked to a Whitmanesque spirit for what they could exalt rather than condemn (with Stieglitz, it could be clouds; with the Photo League, urban working people). As Stieglitz was quoted as saying in Alfred Stieglitz: An American Seer, “Just as I love when there is a rightness in loving for me, so I photograph when I have a positive reaction to what I see. Otherwise, I am silent.”

Another major figure of American photography in this period, and the central pillar of the Photo League, was Sid Grossman. An original photographer as well as one of the great teachers of our time (he was head of the League’s Photography School), he passionately believed in photography as a fine art and encouraged everyone around him. Sid’s often heated discussions about photography more than took the place of Montparnasse café-life as a clearing house for ideas about art. I will always be grateful to him, a loyal friend. He believed in me as a photographer (a belief that never wavered) when I was just starting out, and appointed me a teacher of photography, the youngest the League ever had. I cannot think of a worthwhile photographer of the time whom one did not meet at his apartment. (I remember, in particular, one time when Nancy Newhall dropped by to clear up a point about printing values with him.) Needless to say, he had certain ideas and concepts about photography that were not fully shared, and gradually evolved into what can only be called a Photo League approach to photography. In that view, the photographer was not a law unto himself, but rather, a responsible social being, with obligations not only to subject matter, but to the people engaged in the mass struggles of our time. The Photo League members saw the photograph as a raw but vivid experience of what was most vital and significant between photographer and reality. While they extolled photography as the art form of the twentieth century, they did not see it as an isolated medium, but one enriched and broadened by social and political involvement. Sid believed that a photograph is important to the extent that the photographer becomes emotionally or passionately moved by reality. He felt that only on a basis of emotion could a photographer come to grips with what was around him, and wanted to see that emotion in the final photograph.

The League taught me that the real impetus for historical change did not come from moguls of entertainment or industry, but rather, from the real life-force of people themselves. At the same time, it cautioned against idolizing the people and seeing them as quaint or picturesque, encouraging instead a profound give-and-take of feeling between photographers and their subjects. It frowned upon taking pictures of so-called “bums” or derelicts (today we call them street-people) sleeping or passedout on the street (though it was a subject dear to Weegee, nevertheless). You will rarely see such photographs in League work—it was considered trite and overdone, bordering on needless sentimentality (what the French call miserabilism).

Sid had a profound belief in humanity. “You must know that people can enrich you and you them,” he once said. A good part of his extraordinary development as a human being, teacher, and photographer can be traced to his strong conviction in humanism as a primary source of inspiration. He had a faith in the creative potential of people and in their ability to solve critical problems. It was this same faith in his students that brought out the best in them.

Sid’s organizing activities were also based on his grasp of a fundamental truth that only a few photographers realize today: that it takes gifted photographers and a sympathetic, aware public to produce great photographs. Even the most talented photographers have to be encouraged by responsive and qualified people if they are to develop. Sid realized all too well that his own growth as a photographer depended on such contact.

His photographs also embody his unusual theories and techniques of printmaking. In order to highlight the intended emotional content, he believed in pushing the possibility of the print to the most extreme limits, and even went so far as to use potassium ferrocyanide in the process. When all possibilities of paper contrast, dodging, or burning-in had been exhausted, he lightened shadows, or brought out certain detail with the use of ferrocyanide. He also used “new coccine,” a dye applied directly to the back of the negative with a brush, to lighten shadow areas. Naturally, these techniques gave him greater control over tonalities of the print than did straight printing, and these same formulas were to be adopted and developed by Eugene Smith.

Sid Grossman’s background was unusual. Most Photo Leaguers came from middle-class families, but Sid, like Weegee, came from the poorest working class. His father was a ditchdigger. I remember him telling me of the bitter poverty experienced by his family, who went with hardly anything to eat for months at a time (this was before welfare and unemployment insurance). Sid never graduated from high school—he was that very rare bird, a self-taught working-class intellectual. From his working-class background, he brought to photography a realism about life and a compassion for and loyalty to those who worked hard. Early in Photo League days, a lasting friendship developed between Sid and Charles Pratt, a fellow photographer, former student, and millionaire, whose family owned part of Standard Oil and founded Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. It was touching to witness their friendship, based on mutual affection and their common love of photography, overcome all those class barriers. After Sid’s death, Charles Pratt was to publish From Here to the Cape, a tribute to his friend’s life and photography.

In his last years, Sid spent every summer in Provincetown, photographing the ocean and surroundings. This retreat in his life came after a harrowing time, when he and the Photo League were mercilessly persecuted by Senator Joe McCarthy and the other red-baiters of the early fifties. Despite his tough, Lower East Side manner, Sid was a very sensitive, shy human being, who, after this ordeal, could no longer approach people in the street with a camera. Turning to the beaches and ocean of his beloved Provincetown, he was working on this series of nature images when he died of a heart attack in 1955. On many levels— through his photographs, his work in the Photo League, and his influential relationships with many photographers—Sid Grossman left an important legacy in photography.

Weegee was another strong figure associated with the League—albeit in a curious, ambivalent way. The League was the first to recognize his work, giving him his first one-man show. In 1940, when Weegee started to work for the liberal newspaper PM, where he was treated royally (with a weekly stipend and the first by-line ever given a newspaper photographer in American journalism), he met several colleagues, such as Morris Engel, who belonged to the Photo League. Whenever he came to League gatherings, he was sure to receive a healthy dose of hero-worship or just plain attention which he adored. The trouble was that Weegee could never quite get over his years as freelance photographer, during which time he engaged in a fierce competition with other photographers. Having always functioned alone, he was wary of any comradeship with his fellow photographers. (Our own very close friendship was confirmed only when he fell sick once in Paris, and my girlfriend and I looked after him for a few days. This was something he never forgot, often declaring in exaggerated fashion that I had saved his life. After that, he was a loyal and true friend for twenty-five years.)

Weegee was somewhat anti-intellectual, leery of any kind of discussion about the purposes of photography, referring to those who engaged in such analysis as “egg heads.” Having quit public school at an early age, he felt insecure when too many sentences with ideas flew around. Nor could he share the often lofty ideals and optimism about human nature expressed by Photo Leaguers. Weegee, used to daily murder, rape, arson, and almost any kind of human evil, somehow managed to remain a humanist—but he retained a healthy skepticism withall. Of course, Weegee was not without principles: I remember his declaration (at a big financial loss) to have nothing further to do with an editor who had once paid him ten dollars a photograph, but who cut a print in half and used it twice without payment or acknowledgment.

It was particularly interesting to watch the relationship between Weegee and Sid Grossman. Both came from the same background, New York’s Hell’s Kitchen, and both left school to work at an early age. They understood each other only too well. In 1944, with the publication of Naked City, Weegee became an overnight celebrity, with Park Avenue society women practically begging to ride around with him in his news car at night to cover stories. He grew sarcastic about his fellow photographers and the Photo League, and though most of us at the League were amused and indulgent, Sid never quite forgave him—he saw Weegee betraying his own past, and the class to which they belonged. He accused him of allowing his head and soul to be turned by success and easy money. Unfortunately, much of what he said was to prove true: Weegee went to Hollywood expecting even greater fame and fortune, and instead, for eight years, produced nothing photographically worthwhile. (Weegee himself told me he considered Naked Hollywood to be very bad.) He humiliated himself in bit-roles, caricaturing the very people he had so wonderfully portrayed in Naked City. It took him years to return to New York and become his old self. Later on in life, after the Photo League was destroyed by McCarthyism, 1 never once heard Weegee speak a bad word about the League. Oddly enough, he came to share much of its humanism. I heard him once comment with compassion about his photograph, “Summer, Fire Escape” (children sleeping outside to escape the terrible heat of the slums) : “Those tenements are gone now, and thank God!” Perhaps, in some ways, Weegee also understood the truth: some of the League liberals, who supposedly shared high ideals with Sid and the rest of us, were the first to run when the witch-hunt turned on us.

It is true that the very-successful and those firmly part of the establishment tended to have very few contacts with the Photo League. Among Life magazine photographers, Eugene Smith (himself a rebel there) was the only one to regularly stay in touch with the League. And once, Eliot Eliofson did come to the League to give a lecture on his African shooting safari, during which for some reason he went into bizarre detail about leopard-tracking and droppings. More regular contact was kept with those from abroad, like Manuel Alvarez Bravo and Henri Cartier-Bresson, who realized the Photo League was a vital hub of photography in New York.

Any human endeavor has its shortcomings, and the Photo League was no exception. Looking back, it strikes me that at times meaningful content was given too much precedence over original esthetic form. Banal treatment was tolerated if the subject matter was right. The Stieglitz and Strand traditions, besides their considerable positive influences, overemphasized printing technique while ignoring the necessity for original inner structure in a photograph. Similarly, formalized repetition of subject matter was so prevalent that it practically became necessary for photographers to take pilgrimages to the Lower East Side of New York City. Perhaps it was not possible at the time—all efforts had to be focused on the immediate tasks—but it would have been more meaningful to have a broader cultural and historical base. Many of the solutions to the photography problems at the time would have been enriched by a study of early American photographers, European painting, the Bauhaus, and contemporary American painting almost religiously ignored by the Photo League. The one theoretician among us, Elizabeth McClausland, said much that was valid, but not broad enough in scope. We tended toward a narrow specialization that was never enriched or redefined by the photographers themselves as they progressed in their work. By contrast, Stieglitz and his Camera Work, encouraged numerous credos, manifestos and statements of position by art critics and photographers. But these criticisms are minor.

Oddly enough, the writing on the Photo League has focused most accurately on its demise, so much so that the story hardly bears repetition. The Soviets exploded their atomic bomb, Truman started a furious witch-hunt, and the Photo League became one of its first victims. What has not been recorded was the terrible personal anguish inflicted on many members. Not only did many find themselves destitute, which was bad enough, but they also found themselves alone, walking down a street to find supposedly good friends not daring to say hello to them. Working in Paris at the time for a Marshall Plan project, I was called in one day to the local FBI office. I remember being struck by the agent’s very long, flat, black shoes. He showed me a document recording my association with the Photo League, and asked me for the names of communists in the League. I said that not only were my fellow Photo League members friends, but whatever political affiliations they might have was for them to divulge. The discussion ended. Once back at the office, I was told I could no longer work for the Marshall Plan. Since I knew I could live on very little in Paris, I did not mind very much— French bread and cheese were very good and the vin ordinaire was better than anything I could get in New York. However, money for paper and film was a problem. What puzzled me was an unanswered question: where was the freedom I fought so hard for as a combat photographer in World War II? U.S. officials could become very mean when they encountered anyone who suggested to them that there could be an economic system that might work better than capitalism. I saw the FBI man a few days later near the American Embassy carrying a very large bag of groceries from the PX exchange. To my surprise, he nodded hello. I thought I detected a certain respect—much like that of the executioner who compliments a particularly brave victim. His long black shoes struck me as even longer than before.

Photo Leaguers were also very partial to their subject matter, America’s working people in the urban environment. They did not approach their subjects objectively, but subjectively, with a passionate belief in their qualities, dignity, and ultimate worth. It is these characteristics that distinguish Photo League photographs.

The Photo League experience relates to today’s contemporary photography in ways which underscore its unique character and importance. Starting in the late sixties, photography as a fine art began to blossom in the universities, galleries, and institutions. By the early seventies, photography had become, in the words of Paul Strand, “a salable commodity, and I suppose on the whole this is a good thing.” Perhaps, but a number of negative tendencies have since developed in photography, not the least of which has been an almost complete break with the humanist-realist tradition as expressed in the Photo League.

The new art establishment, for the most part, encourages “belly-button” photography, claiming the photographer’s inner vision is everything, and reality something that can be manipulated at will. Humanist realism does not deny the primary importance of personal vision, but it does not attribute everything to it. Academia has encouraged photographers to ignore political and social content and to concentrate on form. They call this formalism. (I call it self-indulgent estheticism.) Less serious photographers will concentrate on the corners of rooms or gimmicks or handles that are glitzy and fashionable. As a result of the McCarthy period and the Vietnam War, academics were told in no uncertain terms to keep out of politics and to stay away from the real world, a warning that, in general, has been well-heeded. Today, most photographers (expressing their own estrangement), portray people as lifeless puppets or helpless victims of a system they can neither understand nor change. Writing about early twentieth-century art, the English critic Alistair Mackintosh pointed out: “It is an ironic truth that the moment when art claims to be “above” contemporary life is always the moment it becomes controlled by it.” The separation of human vision (including artists) from its social, historical, and cultural context represents a phase that art has passed through before. It is called anticlassicism. As Walter Friedlander states: “The whole bent of anticlassic art is basically subjective, since it would construct and individually reconstruct from the inside out, from the subject outward, freely, according to the rhythmic feeling present in the artist, while classic art, socially oriented, seeks to crystallize the object for eternity by working out from the regular, from what is valid for everyone.”

The current anticlassic style in photography is also due in part to the huge wave of consumerism that began in the late fifties. Introduced as a mass medium in the early fifties, television has gradually become overpowering and overwhelmingly effective. During the Photo League era, the average American still had strong social ties to the community and the work place. Recreation and entertainment were, for the most part (though there were also movies), tied to activity in the immediate environment, and not to the world of the TV tube and the allpervasive, authoritative voice of the establishment. Much of the appeal of Robert Frank’s 1958 book of photographs, The Americans, is its emphasis on the growing sense of the individual’s helplessness before a system that he could neither control nor comprehend. It correlated directly with the American intellectual’s growing sense of despair.

Entertainment TV changed the very content of fine art: the artist was expected to be an entertainer. TV’s bright colors, tricky images, and high-tech illusion postulated that life is essentially witty, funny, and worth living. Eventually crime, murder, drugs, and poverty could be portrayed as easily digestible— and even entertaining—commodities. The mass media fashioned the artist as a sort of visual performer whose function no longer was to spiritually nourish, but to entertain his audience. The high prices and quick fame offered by Hollywood, slick galleries, and well-heeled publishers only accelerated this image. Here and there, though, genuine art is being done—there are a few receptive galleries and institutions. Yet, sometimes protest can take strange, devious paths. The photographs of Joel Peter Witkin, which in some respect are examples of explosive pornographies, express vividly, in their most positive sense, the frustrations of a photographer unable to relate to his world.

This is not to rule out subjectivity. After all, things are seldom the way they seem. An apple is never just an apple to an artist. But the point is that some artists strike a resonant balance between the interior and exterior worlds. Several years ago in Art News, a critic quite rightly pointed out that Cezanne’s apples were not just his own personal interpretation of apples; they were also enriched by Cezanne’s affinity and deep appreciation for the French peasant. They embodied the hard toil and patient care of the working man. Cezanne’s apples reflect not only the beauty of nature but also man’s effort to nourish and transform it. By giving political content to his apples, Cezanne raised them from being “nice” academic still lifes to statements of great beauty and meaning.

The Photo League was part of the humanist-realist tradition in photography which goes back through Strand, Stieglitz, Hiñe, and David Octavius Hill. It is a vision based on interpreting the world around us, focused on human beings in their society and culture—the prime motivating force in this universe. The Photo League was a unique group expression of a profound humanist thrust in our century which immeasurably enriched American culture. It has been my good fortune to have been part of that experience.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

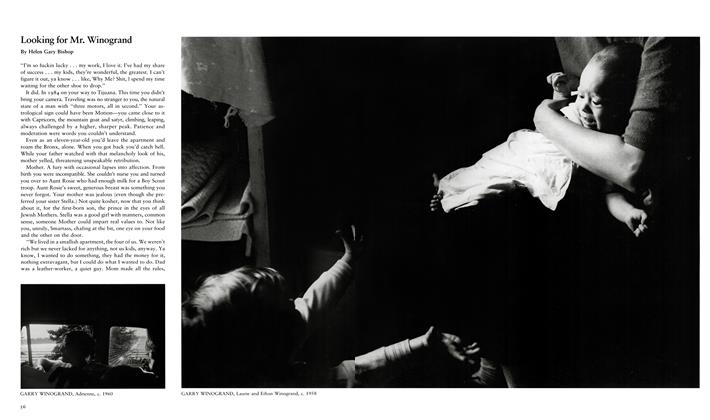

Looking For Mr. Winogrand

Fall 1988 By Helen Gary Bishop, The Editors -

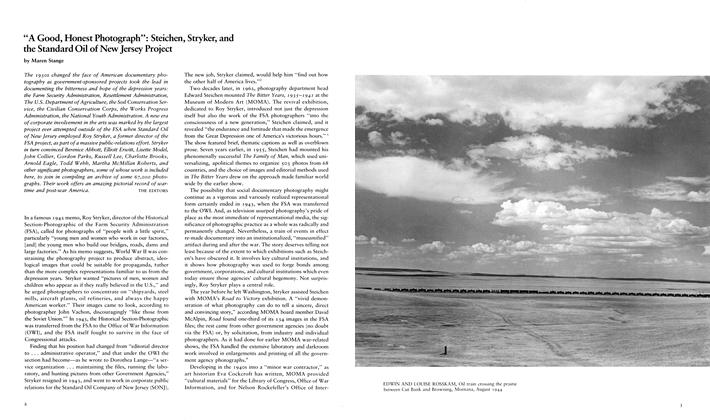

"A Good, Honest Photograph": Steichen, Stryker, And The Standard Oil Of New Jersey Project

Fall 1988 By Maren Stange -

Questioning Documentary

Fall 1988 By Brian Wallis -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasAfter Agee

Fall 1988 By J. Ronald Green -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasA Commentary On Eugene Richard's Below The Line

Fall 1988 By Robert Cole -

Notes

NotesNotes

Fall 1988