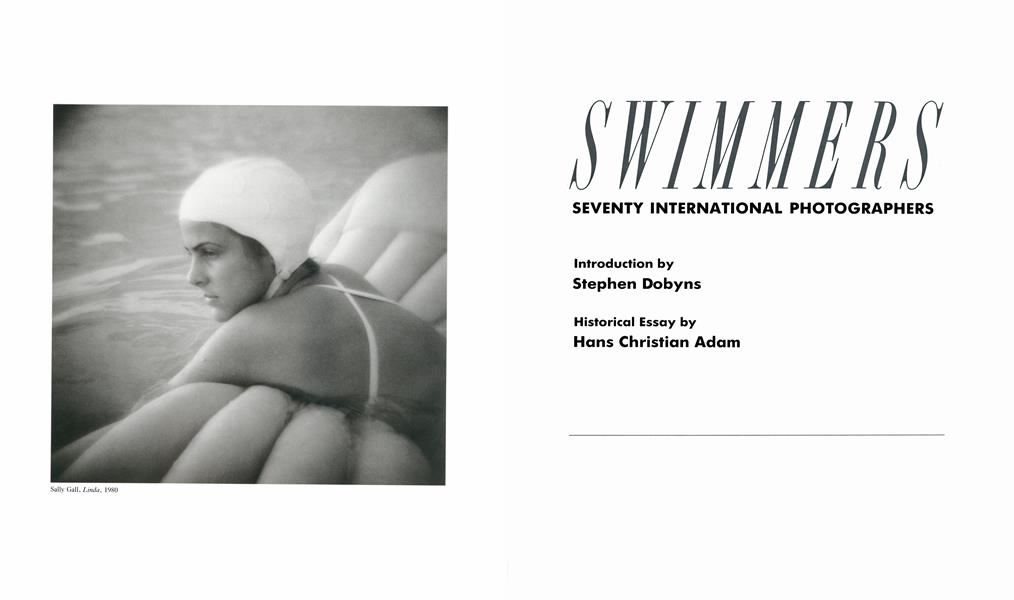

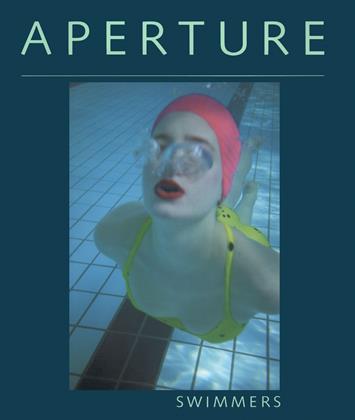

SWIMMERS

SEVENTY INTERNATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHERS Stephen Dobyns Hans Christian Adam

MERMAIDS

STEPHEN DOBYNS

In the painting "The Depths of the Sea" by Edward Burne-Jones, the mermaid's arms are wrapped tightly around the young man's waist, pinning his hands behind him. They have sunk far below the surface. The last air bubbles are leaving the man's mouth. His eyes are shut and he appears unconscious. The mermaid’s expression is one of proprietary rapture with perhaps a hint of doubt. The man may be hers but he is also dying. The mermaid’s golden tail flicks the bottom which seems covered with gold coins. They each had a great desire and that desire has destroyed them.

Burne-Jones’s painting captures that element of yearning which the sea can so often bring out in us—the desire to transcend ourselves, to take on another nature, to push aside the laws that bind us, to court a beautiful danger. When swimming, I become graceful. I have put aside my body and have borrowed something from the seal. This is partly why I do it. It doesn’t quite allow me to transcend myself, but it gives me a hint of what transcendence might be like. To some degree the water allows us to become what we are not, while giving us a taste of what we can never become.

Years ago I used to swim laps at the YMCA Pool in Cambridge, Massachusetts. One of the other swimmers was blind. He was a college student somewhere. Clumsy, slow, unsure of himself, he didn’t so much have a stroke as dozens of jerky motions to propel himself forward. But there was one place where I envied him. On those days when the pool was nearly empty, he would make his way around to the diving board. Slowly, he would climb onto it and begin to feel his way to the end with his toes, keeping his arms stretched out on either side for balance. When he was at last perched on the very tip, he would call out, “Is it all clear?”

If the lifeguard answered yes, the blind swimmer would bounce and leap high into the air—all control gone, arms and legs flapping and kicking, as he broke free for a moment of his mortal body. For an instant he was pure joyous spirit hanging above us. And what a grin he had during those few seconds in the air. So eager was he for his manic dive, that he rarely waited for the all-clear. He would leap wildly off the board, whether there were swimmers beneath him or not, and send us sighted swimmers scrambling for the sides, while he, high above us, momentarily escaped the burden of the physical world.

Gravity is both our protector and jailer and we love those short periods when we are free of it. Plunging through the surf, we gladly let the water lift our weight from us. Adults suddenly have the bodies of children, and children have bodies of air. The physical world has been temporarily defeated. One’s mortality diminishes, becomes unimportant. Even the word buoyancy means elasticity of spirit, cheerfulness.

Yet this water can kill us. The ocean’s offer to let us become something we are not has its menacing aspect. The young man wrapped in the mermaid’s embrace has made a serious mistake. The sirens singing to Odysseus mean him no good; even though they promise wisdom, they intend death. They also sing to Jason and the crew of the Argo in their quest for the golden fleece. Their song is unbounded desire, the desire to leave their bodies and enter a purely sexual element. The oarsmen, hearing the song, turn the Argo toward the reef which would destroy it. Even Jason is defeated. But then Orpheus picks up his lyre and begins to play, setting against the siren’s music an even sweeter music, setting structure against cacophony, form against formlessness. Through his music, Orpheus reaffirms the orderly world. The Argo resumes its course. Defeated, the sirens fling themselves into the sea, where they become rocks.

But not only is there danger in water, there is mystery. We are quick to believe in mysterious ships, creatures coming out of the depths, strange disappearances. As Percy Bysshe Shelley left Leghorn Harbor in a small sailboat, the mate of another boat observed to Shelley’s biographer Trelawny, “Look at those black lines and the dirty rags hanging on them out of the sky—they are a warning; look at the smoke on the water; the devil is brewing mischief.”

Shelley’s boat sailed into the mist, and that was the last that was ever seen of him. A sudden squall, and nearly four weeks later his body was found washed up on the shore near Via Reggio, his face and hands gone, a copy of Sophocles in one pocket, a copy of Keats in the other. Trelawny built a furnace on the beach and the body was burnt. “The only portions that were not consumed,” he wrote, “were some fragment, of bones, the jaw, and the skull, but what surprised us all, was that the heart remained entire. In snatching this relic from the fiery furnace, my hand was severely burnt.”

It is hard to look at the water without thinking of people and friends whom we have known who have drowned—a high-school friend tangled in the weeds while scuba diving, a man who fell from his sailboat on a lake in Maine and couldn’t swim. We all know people who have gone too far into the water, who have taken one chance too many. Death, too, is a kind of transcendence. It makes the water terrifying and gives it an additional nuance of beauty.

Often in summer I swim in various lakes in New Hampshire and Maine, measuring out a distance of about a mile, then swimming out into the deep water. Usually I can see down about five to ten feet, then all becomes black. It is like swimming over fear itself, swimming over one’s unconscious mind. I think of Jaws and the shark coming up out of the darkness. Once, in Maine, I saw an eel about six feet long curled up on the bottom of a lake. Its terror on seeing me was far greater than mine, but for a moment my fear was so primitive that I nearly scrambled for land. But even the eel felt like something deep within me, a projection of my unconscious, as if by erasing my body in the water, the lake had become an extension of myself. Swimming over such a darkness, I always felt on the very brink of learning something important, something to change my life.

In many ways, the photographs in this collection all deal with transcendence, the body triumphing over gravity, of defeating for a short time its mortal cage. How graceful these bodies become. Even the fat boy running down the beach seems ready to fly. And the old man drifting on a float has escaped himself for an afternoon. Picture after picture shows people of all ages leaping into the waves, as if intending to reverse the process of evolution. They dive into the water as if returning home—eager, excited, exhilarated. It takes their breath. They leave their lumpish selves and enter their beautiful selves. They exist at the very edge of being human. Several photographs show boys so covered with sand that they look like statues erected to their own memories. These water-goers hope to push beyond their quotidian lives, to forget the sunburns, the sand in their sandwiches, the long drive home through heavy traffic.

The subject of these photographs is also timelessness. There is no past or future at the beach. It is a time-out period. Beyond that, the waves have counted out the seconds since the beginning, yet it’s as if each second and wave were the same moment, repeated over and over. Entering the water we leave time behind, we defeat the world. Perhaps that is why there is so much joy in these pictures. Constant laughter, constant smiles— the joy at having briefly escaped our mortal destiny.

The photographs are also about space—the small, puny, soft body poised against the seemingly endless ocean and sky: a woman holding her child as she stares into the blue nothingness; three boys dashing out into the infinite; several girls on a white raft silhouetted against the massive dark of the night. They show the human, the small, at the very edge of limitlessness, taunting it, playing with it, losing one’s self in it.

Water is purifying. Stepping into it, the world of gravity is washed from us. All our stains come clean; our griefs and difficulties are temporarily forgotten. In entering the timelessness of the water, we, too, for a brief space, become without a past. This strengthens us and we return to the world eager and even optimistic about the struggle. The ocean, or so we used to imagine, cannot be dirtied. An early discredited saint, St. Murgen, was a mermaid who had been caught and baptized in northern Wales, and then spent her life doing good works. Having come from the sea, she seemed specially equipped to cleanse the world.

We like to imagine that no matter how life has sullied us, the water can make us pure again. It is almost as if we are receiving the forgiveness of the world. We are being given another chance, a secular baptism. Pablo Neruda wrote a wonderful poem of a mermaid, trapped and dirtied on land, who has only to return to the water to be cleansed. It brings us full circle: Burne-Jones’s mermaid with the man as her victim; Neruda’s mermaid who is the victim of the drunks. And again we are in the presence of mystery.

FABLE OF THE MERMAIDS AND THE DRUNKS

All these gentlemen were there inside when she entered, utterly naked. They had been drinking, and began to spit at her. Recently come from the river, she understood nothing. She was a mermaid who had lost her way. The taunts flowed over her glistening flesh. Obscenities drenched her golden breasts. A stranger to tears, she did not weep. A stranger to clothes, she did not dress. They pocked her with cigarette ends and with burnt corks, and rolled on the tavern floor with laughter. She did not speak, since speech was unknown to her. Her eyes were the color of faraway love, her arms were matching topazes. Her lips moved soundlessly in coral light, and ultimately, she left by that door. Scarcely had she entered the river than she was cleansed, gleaming once more like a white stone in the rain; and without a backward look, she swam once more, swam toward nothingness, swam to her dying.

SEXUAL WATER

Rolling in big solitary raindrops, in drops like teeth, in big thick drops of marmalade and blood, rolling in big raindrops, the water falls, like a sword in drops, like a tearing river of glass, it falls biting, striking the axis of symmetry, sticking to the seams of the soul, breaking abandoned things, drenching the dark.

It is only a breath, moister than weeping, a liquid, a sweat, a nameless oil, a sharp movement, forming, thickening, the water falls, in big slow raindrops, toward its sea, toward its dry ocean, toward its waterless wave.

I see the vast summer, and a death rattle coming zfrom a granary stores, locusts, towns, stimuli, rooms, girls sleeping with their hands upon their hearts, dreaming of bandits, of fires, I see ships, I see marrow trees bristling like rabid cats, I see blood, daggers, and women’s stockings, and men’s hair, I see beds, I see corridors where a virgin screams, I see blankets and organs and hotels.

I see the silent dreams, I accept the final days, and also the origins, and also the memories, like an eyelid atrociously and forcibly uplifted I am looking.

And then there is this sound: a red noise of bones, a clashing of flesh, and yellow legs like merging spikes of grain. I listen among the smack of kisses, I listen, shaken between gasps and sobs. I am looking, hearing, with half my soul upon the sea and half my soul upon the land, and with the two halves of my soul I look at the world.

And though I close my eyes and cover my heart entirely, I see a muffled waterfall, in big muffled raindrops. It is like a hurricane of gelatine, like a waterfall of sperm and jellyfish. I see a turbid rainbow form. I see its waters pass across the bones.

PABLO NERUDA

Before descending to the alluvial plain, To the clay banks, and the wild grapes hanging from the elmtrees. The slightly trembling water Dropping a fine yellow silt where the sun stays; and the crabs bask near the edge, The weedy edge, alive with small snakes and bloodsuckers-

I have come to a still, but not a deep center, A point outside the glittering current; My eyes stare at the bottom of a river, At the irregular stones, iridescent sandgrains, My mind moves in more than one place, In a country half-land, half-water....

The lost self changes, Turning toward the sea, A sea-shape turning aroundAn old man with his feet before the fire, In robes of green, in garments of adieu.

A man faced with his own immensity Wakes all the waves, all their loose wandering fire. The murmur of the absolute, the why Of being bom fails on his naked ears. His spirit moves like monumental wind That gentles on a sunny blue plateau. He is the end of things, the final man.

THEODORE ROETHKE, from The Meadow Mouse

For Naomi, later

I want to speak to you while I can, in your fourth year before you can well understand, before this river white and remorseless carries me away.

You asked me to tell you about death. I said nothing. I said

This is your father, this is your father like water, like fate, like a feather circling down.

And I am my own daughter swimming out, a phosphorescence on the dark face of the surf. A boat circling on the darkness.

ROBERT MEZEY from I Am Here

PAEAN TO PLACE

And the place was water Fish fowl flood Water lily mud My life in the leaves and on water My mother and I bom in swale and swamp and sworn to water My father thm marsh fog sculled down from high ground saw her face at the organ bore the weight of lake water and the cold— he seined for carp to be sold that their daughter might go high on land to learn Saw his wife turn deaf and away She who knew boats and ropes no longer played She helped him string out nets for tarring And she could shoot He was cool to the man

who stole his minnows by night and next day offered to sell them back He brought in a sack of dandelion greens if no flood No oranges—none at hand No marsh mangolds where the water rose He kept us afloat I mourn her not hearing canvasbacks their blast-off rise from the water Not hearing sora rail’s sweet spoon-tapped waterglassdescending scaletear-drop-tittle Did she giggle as a girl? His skiff skimmed the coiled celery now gone from these streams due to carp He knew duckweed I lost you to water, summer when the young girls swim, to the hot shore to little peet-tweetpert girls. Now it’s cold your bright knock —Orion’s with his dog after him— at my door, boy on a winter wave ride.

LORINE NIEDECKER

Cold water on my bare feet. You are like cold water.

All day I’ve watched the water run from the tap, splash into the bushes where the earth awaits it and sucks it up.

Cold water! The grass exclaims.

LOU LIPSITZ

THE NUDE SWIM

On the southwest side of Capri we found a little unknown grotto where no people were and we entered it completely and let our bodies lose all their loneliness.

All the fish in us had escaped for a minute. The real fish did not mind. We did not disturb their personal life. We calmly trailed over them and under them, shedding air bubbles, little white balloons that drifted up into the sun by the boat where the Italian boatman slept with his hat over his face.

Water so clear you could read a book through it.

Water so buoyant you could float on your elbow. I lay on it as on a divan. I lay on it just like Matisse's Red Odalisque. Water was my strange flower. One must picture a woman without a toga or a scarf on a couch as deep as a tomb.

The walls of that grotto were everycolor blue and you said, “Look! Your eyes are seacolor. Look! Your eyes are sky color.'' And my eyes shut down as if they were suddenly ashamed.

ANNE SEXTON

THE LIFEGUARD

In a stable of boats I lie still, From all sleeping children hidden. The leap of a fish from its shadow Makes the whole lake instantly tremble. With my foot on the water, I feel The moon outside Take on the utmost of its power. I rise and go out through the boats. I set my broad sole upon silver, On the skin of the sky, on the moonlight, Stepping outward from earth onto water In quest of the miracle This village of children believed That I could perform as I dived For one who had sunk from my sight. I saw his cropped haircut go under. I leapt, and my steep body flashed Once, in the sun. Dark drew all the light from my eyes. Like a man who explores his death By the pull of his slow-moving shoulders, I hung head down in the cold, Wide-eyed, contained, and alone Among the weeds. And my fingertips turned into stone From clutching immovable blackness. Time after time I leapt upward Exploding in breath, and fell back From the change in the children’s faces At my defeat. Beneath them I swam to the boathouse With only my life in my arms To wait for the lake to shine back

At the risen moon with such power That my steps on the light of the ripples Might be sustained. Beneath me is nothing but brightness Like the ghost of a snowfield in summer. As I move toward the center of the lake, Which is also the center of the moon, I am thinking of how I may be The savior of one Who has already died in my care. The dark trees fade from around me. The moon’s dust hovers together. I call softly out, and the child’s Voice answers through blinding water. Patiently, slowly, He rises, dilating to break The surface of stone with his forehead. He is one I do not remember Having ever seen in his life. The ground I stand on is trembling Upon his smile. I wash the black mud from my hands. On a light given off by the grave I kneel in the quick of the moon At the heart of a distant forest And hold in my arms a child Of water, water, water.

JAMES DICKEY

PLEASURE SEAS

In the walled off swimming-pool the water is perfectly flat. The pink Seurat bathers are dipping themselves in and out Through a pane of bluish glass. The cloud reflections pass Huge amoeba-motions directly through The beds of bathing caps: white, lavender, and blue. If the sky turns gray, the water turns opaque, Pistachio green and Mermaid Milk. But out among the keys Where the water goes its own way, the shallow pleasure seas Drift this way and that mingling currents and tides In most of the colors that swarm around the sides Of soap-bubbles, poisonous and fabulous. And the keys float lightly like rolls of green dust. From an airplane the water’s heavy sheet Of glass above a bas-relief:

Clay-yellow coral and purple dulces And long, leaning, submerged green grass. Across it a wide shadow pulses. The water is a burning-glass Turned to the sun That blues and cools as the afternoon wears on, And liquidly Floats weeds, surrounds fish, supports a violently red bell-buoy Whose neon-color vibrates over it, whose bells vibrate Through it. It glitters rhythmically To shock after shock of electricity The sea is delight. The sea means room. It is a dance-floor, a well ventilated ballroom. From the swimming-pool or from the deck of a ship Pleasures strike off humming, and skip Over the tinsel surface: a Grief floats off

Spreading out thin like oil. And Love Sets out determinedly in a straight line, One of his burning ideas in mind, Keeping his eyes on The bright horizon, But shatters immediately, suffers refraction, And comes back in shoals of distraction. Happy the people in the swimming-pool and on the yacht, Happy the man in that airplane, likely as not— And out there where the coral reef is a shelf The water mns at it, leaps, throws itself Lightly, lightly, whitening in the air: An acre of cold white spray is there Dancing happily by itself.

ELIZABETH BISHOP

THE BEACH IN AUGUST

The day the fat woman In the bright blue bathing suit Walked into the water and died, I thought about the human Condition. Pieces of old fruit Came in and were left by the tide.

What I thought about the human Condition was this: old fruit Comes in and is left, and dries In the sun. Another fat woman In a dull green bathing suit Dives into the water and dies. The pulmotors glisten. It is noon.

We dry and die in the sun While the seascape arranges old fruit, Coming in with the tide, glistening At noon. A woman, moderately stout, In a nondescript bathing suit, Swims to a pier. A tall woman Swims toward the sea. One thinks about the human Condition. The tide goes in and goes out.

WELDON KEES

“The three mermaids,” Columbus relates, “raised their bodies above the surface of the water and, although they were not as beautiful as they appear in pictures, their round faces were definitely human.”

LEVI-STRAUSS in Tristes Tropiques

X

After the rains left Macondo in Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, Aureliano Segundo asks the survivors how they survived the four years, eleven months and two days of rain, how they managed to not go awash, and all gave the same answer: swimming.

Now here, a feeling not unlike that of Verrocchio’s Baptism comes over me as I glide through the water, my fingers arced upward as in prayer,

my head bowed in a kind of penance and forgetfulness.

So perhaps I too will survive by swimming: an amphibian moved first by a stroke of genius, then by a stroke of luck as I weave through these waters, a priest and a penitent both at once, an expiator of my own sins, a quick eel, electric in his own current.

MICHAEL BLUMENTHAL

Sheets of rain, salt lash, wind. The smell of sea and torn vegetation.

Wading across the deck to the spiral staircase, Melissa found it possible, in that blackness, to see the horizontal expanse of the cove—its churning, luminous foam— as a vertical wave about to engulf the house. This optical illusion she alternately entertained and dispelled. Her steps rang faintly on the steel stairs.

Her steps rang faintly on the steel stairs. She could hear the waves crashing in on the wave ramp. She put on the mask. . . . She dived.

It was as though the violent agitation of the surface were a membrane through which she had passed to a place of great familiarity and quiet. This is how you enter certain rooms, certain embraces, this is what a recollection is. She swam downward. . . .

TED MOONEY from Easy Travel to Other Planets

“DOVER BEACH”—A NOTE TO THAT POEM

The wave withdrawing Withers with seaward rustle of flimsy water Sucking the sand down, dragging at empty shells. The roil after it settling, too smooth, smothered . . .

After forty a man’s a fool to wait in the Sea’s face for the full force and the roaring of Surf to come over him: droves of careening water. After forty the tug’s out and the salt and the Sea follow it: less sound and violence. Nevertheless the ebb has its own beauty— Shells sand and all and the whispering rustle. There’s earth in it then and the bubbles of foam gone.

Moreover—and this too has its lovely uses— It’s the outward wave that spills the inward forward Tripping the proud piled mute virginal Mountain of water in wallowing welter of light and Sound enough—thunder for miles back. It’s a fine and a Wild smother to vanish in: pulling down— Tripping with outward ebb the urgent inward.

Speaking alone for myself it’s the steep hill and the Toppling lift of the young men I am toward now, Waiting for that as the wave for the next wave. Let them go over us all I say with the thunder of What’s to be next in the world. It’s we will be under it!

ARCHIBALD MACLEISH