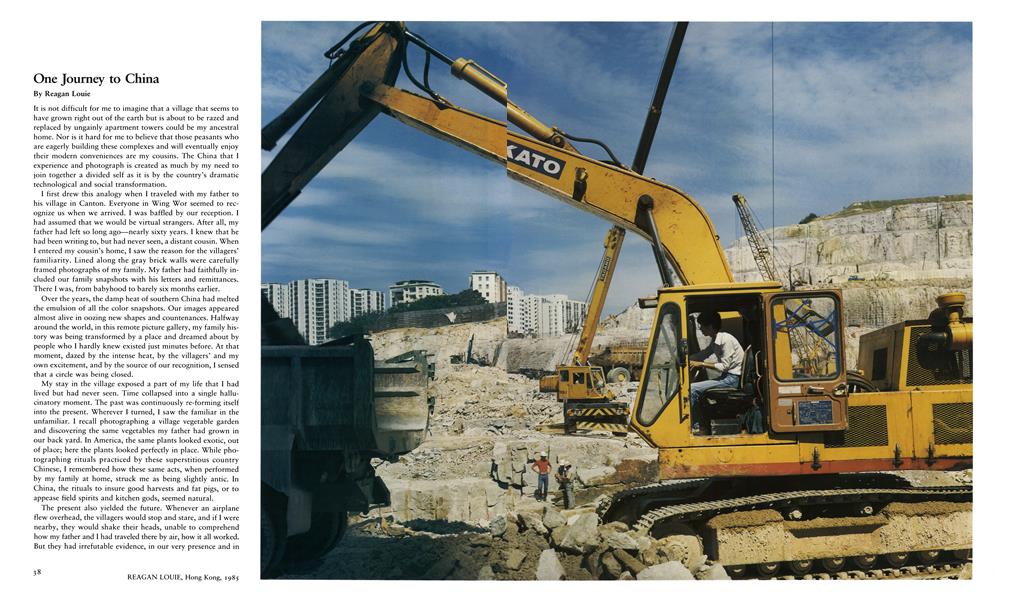

One Journey to China

Reagan Louie

It is not difficult for me to imagine that a village that seems to have grown right out of the earth but is about to be razed and replaced by ungainly apartment towers could be my ancestral home. Nor is it hard for me to believe that those peasants who are eagerly building these complexes and will eventually enjoy their modern conveniences are my cousins. The China that I experience and photograph is created as much by my need to join together a divided self as it is by the country’s dramatic technological and social transformation.

I first drew this analogy when I traveled with my father to his village in Canton. Everyone in Wing Wor seemed to recognize us when we arrived. I was baffled by our reception. I had assumed that we would be virtual strangers. After all, my father had left so long ago—nearly sixty years. I knew that he had been writing to, but had never seen, a distant cousin. When I entered my cousin’s home, I saw the reason for the villagers’ familiarity. Lined along the gray brick walls were carefully framed photographs of my family. My father had faithfully included our family snapshots with his letters and remittances. There I was, from babyhood to barely six months earlier.

Over the years, the damp heat of southern China had melted the emulsion of all the color snapshots. Our images appeared almost alive in oozing new shapes and countenances. Halfway around the world, in this remote picture gallery, my family history was being transformed by a place and dreamed about by people who I hardly knew existed just minutes before. At that moment, dazed by the intense heat, by the villagers’ and my own excitement, and by the source of our recognition, I sensed that a circle was being closed.

My stay in the village exposed a part of my life that I had lived but had never seen. Time collapsed into a single hallucinatory moment. The past was continuously re-forming itself into the present. Wherever I turned, I saw the familiar in the unfamiliar. I recall photographing a village vegetable garden and discovering the same vegetables my father had grown in our back yard. In America, the same plants looked exotic, out of place; here the plants looked perfectly in place. While photographing rituals practiced by these superstitious country Chinese, I remembered how these same acts, when performed by my family at home, struck me as being slightly antic. In China, the rituals to insure good harvests and fat pigs, or to appease field spirits and kitchen gods, seemed natural.

The present also yielded the future. Whenever an airplane flew overhead, the villagers would stop and stare, and if I were nearby, they would shake their heads, unable to comprehend how my father and I had traveled there by air, how it all worked. But they had irrefutable evidence, in our very presence and in those family photographs of our life in America, that it did work,that it worked very well. Other circles were being drawn.

As the first native son ever to return, my father was no less than a local hero. From morning until night, villagers begged him to tell tales about “Gold Mountain.” His return was more than symbolic; it was actual. He moved back through time and memory and became once again that barefoot boy lazily tending the village water buffalo. Witnessing his transformation released a torrent of thoughts, including some about destiny. We are, each one of us, connected to something larger. We seldom, if ever, think about it. Mainly, the connection is lived through in our day-to-day existence. Were it not for an opium war, a gold rush, a transcontinental railroad, and a famine, my father most likely would not have left his village, and this story, if it were told at all, would be very different.

In a slow frenzy, I was trying to fill in a chasm—the before and after of my father’s life. I knew I was measuring my life as well. Rationally, it made elegant sense. The simple necessity of survival forced this peasant boy to leave his home to find a new life in a foreign land. I could see that he left reluctantly. I felt his ease in being here. I could feel his connection. He was at home. For the first time in many years, I looked steadily into my father’s eyes. They always seemed to be filled with tears.

I wish I could say that sharing my father’s journey, and understanding how it caused my own, was an easy process. But I cannot. Competing with all the revelations—the vegetable garden, our family snapshots, my father’s rebirth—were so many memories and feelings that I did not want. I envied my father’s connection to his village. It was one I could never share. It was not my home. I did not have my father’s blood knowledge of this place. Being distantly related allowed me to overcome the peasants’ fierce suspicion of outsiders. But my own suspicion of myself—of my motivations for being here—was less easy to dispel. I was, above all, a photographer. I was an outsider.

When I decided to study art, I felt the need to completely separate from the whole weight of my Chinese self. I am Chinese-American. Rigid Old World traditions and elastic New World myths make conflicting claims on my life. My father spoke only Chinese to me when I was a child yet named me after Ronald Reagan, star of the 1951 hit movie Bedtime for Bonzo.

My decision to separate was probably made for me on the day I entered school. Except for a few stray words, I could not speak English. I learned quickly. And, as quickly, I unlearned Chinese.

All during my schooling, I was gradually cutting away from custom and my past. I knew from my first recreational college art class that I could not fulfill my father’s expectations and become a professional: a doctor, a lawyer, or at the very least a pharmacist. I could not explain my desire to be an artist since I had little understanding of it myself. There was no reason for pursuing such an improbable career. There was no history. By refusing the role expected of a Chinese son, I created a gulf between my family and myself.

It took me only three and a half days to drive 3,000 miles across the country, after a six-year absence, back to my boyhood home in Sacramento. I had just graduated from college. I had no other place to go. At the time, I didn’t know exactly why I had to return. I just knew I had to. Somehow, I recognized that I had to cast a new identity for myself in my old world, full of reminders of who I had been and cues for who I was supposed to be.

Everything and every occasion seemed to be filled by my struggle. I remember evenings when I would chase my parents out of their living room so that I could look at slides of my work. Each time, I would shudder at my callousness and grow tenser about this activity I so dimly understood. Often, as I sat in that darkened room viewing the projected slides on the wall, I would glance through the window, across the street, to my father’s corner market. At other moments, my gaze would turn from those glowing Kodachromes to the flatter but somehow more real family snapshots sitting on top of the television set next to me, and my past would beckon and then take me over.

At those moments, when I regretted the loss of my past, I would quickly remind myself of the bright promise of being an artist. It momentarily strengthened my resolve. But the fact is, this separation was terrifying.

Much of this terror revisited me in China. On more nights than I care to remember, all my fractured selves kept me awake

with the bitter noise of recrimination. On most days, I photographed in wildly fluctuating moods of wonder, rage, enchantment, and embarrassment. The sources of my behavior, of who I was, haunted me.

Since I did not speak the villagers’ dialect and they did not speak English, we could only stare at one another. I rarely spoke, even with my father. My imposed muteness raised and was suffused by a more profound silence. My father and I have never had a highly verbal relationship. He is a man of few words. I learned that his quiet is native; all the villagers seemed to possess an inborn reticence. But I also discovered that his silence had a deeper cause, one that was familiar to me. From my own estrangement, I well understood that his separation was too painful to share openly. He could not have revealed the depth of his loss and survived so far away from his home.

When I grew into my silence, I did so, like my father before me, out of a fear for survival. But our silences are of different kinds. Where he grew literally quiet, I grew more abstractly vocal. There is a forced irony to my voice. If my education has helped me to grow culturally divided, it has also given me the ability and means to describe this division. I am wary of this voice. As I write these thoughts, I warn myself against a phrase too well turned, a word too abstract. They may betray me, blocking a connection that I desperately need to make. Each sentence is a struggle against my silence.

There are times when I am even wary of my photographs, especially my “successful” pictures. They, like my words, are well schooled. They may be evasions. “Formalism is repression,” I once heard. The more beautiful, the more silent? Still, inescapably, my photographs and my words, wedged between selves, are double edged, both cause of and cure for my separation.

I have no doubt that this separation and the need to close it brought me to China, to my father’s home. On our last day in the village, I remember watching my father, in front of his old house, holding my cousin’s baby. As I sat across from them, fanning myself against the heat, they blurred into scenes I recalled from two old family photographs. I stepped sixty years back, and in front of me stood my father as a child leaning against his father in the doorway of this house. A moment later, I was in old Sacramento, where my father was proudly displaying his new son in front of his new market, called the American Way.

In the clearest moments, I see myself as a transitional figure, bridging cultures and maybe even time. Journeying back with my father to China taught me that he too is a transitional figure. I’m continuing a passage that began when he left his village. Only, instead of exploring a new physical territory, I’m charting a new psychic region. It’s a shifting ground somewhere between East and West, knowledge and need, then and now.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Front Matter

Spring 1987 -

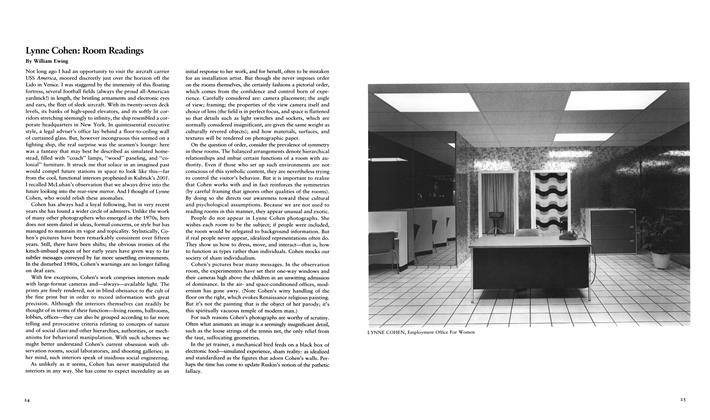

Lynne Cohen: Room Readings

Spring 1987 By William Ewing -

Patterns Of Light

Spring 1987 By Kira Perov -

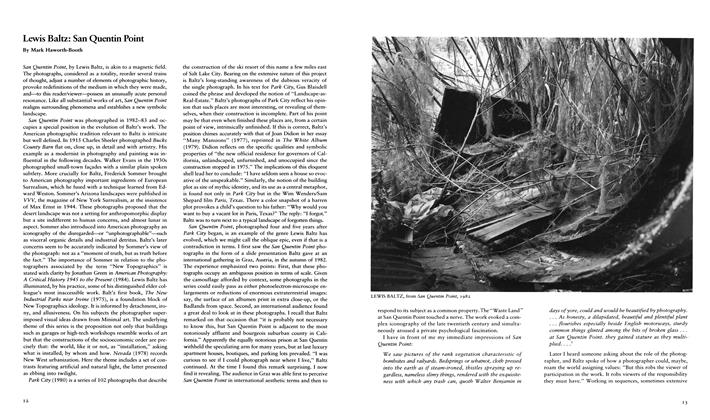

Lewis Baltz: San Quentin Point

Spring 1987 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

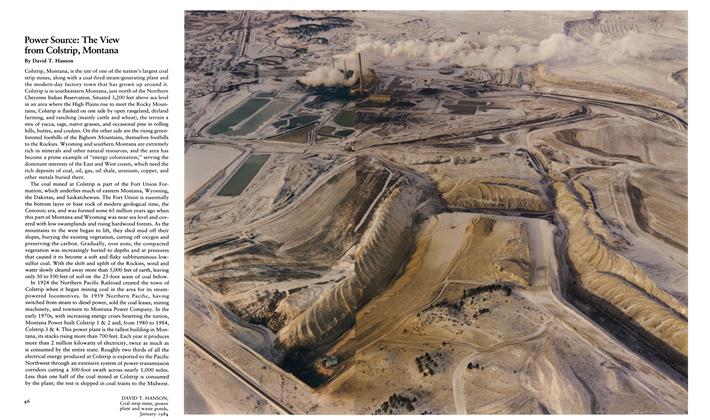

Power Source: The View From Colstrip, Montana

Spring 1987 By David T. Hanson -

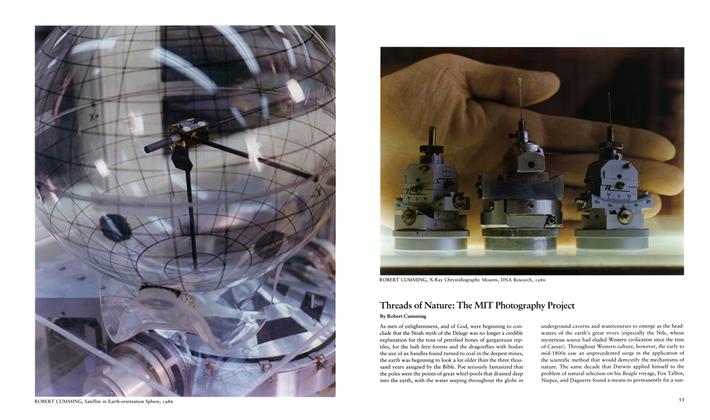

Threads Of Nature: The Mit Photography Project

Spring 1987 By Robert Cumming