THE HEART OF THE INEFFABLE

Estelle Jussim

Mothers and daughters! Are there any fantasies or ideal images left to us in this tough-minded age of psychological realism? Do we still yearn (without admitting it) for the imagined paradise of lost Mother-Daughter delights that some of us have never known? Psychologists tell us that Mother is that allgiving, all-dominating, all-powerful figure from our fairy-tale infancies, the giant in the nursery. She is transmuted into the evil stepmother of those tales, yet simultaneously she is also the life-enhancing, sweetly tender goddess whose beauty, goodness, and self-sacrifice we could never hope to equal. Ultimately, she seems to contain all the mysteries of adulthood.

Daughter, on the other hand, simply connotes a biological relationship, a social role of no great consequence, and (depending on the culture into which a daughter is born) an expensive liability requiring dowries and protection. A society that devalues women in general may decide that the birth of a daughter is an unaffordable luxury, since she cannot become a warrior, a hunter, or a chief. Fortunately, most human groups no longer dispose of their daughters on the nearest hilltop. But, as we look at the pictures in this collection, we should keep a firm grasp on our history, for even in the relatively few decades we have enjoyed photography, the changing iconography that inevitably accompanies changing social attitudes is conspicuous and tangible.

It has been widely recognized that even the greatest portrait can capture only so much of an individual’s personality and character, not all of that person’s physical attributes, and certainly not a permanently ascribable mood. An attempt by a photographer to convey not only one, but two persons and their relationship, might seem to be exceedingly difficult, if not impossible. To portray two persons defined as mother and daughter is to define a relationship fraught with cultural and emotional overtones. Such intensity of meaning would seem to demand skillful decoding. Perhaps, also, it requires a grasp of visual language that not all of us possess. Even if we did possess such a visual language, it might prove to be so ethnocentric and tempocentric as to defy our desires for significant universal meanings. This collection makes no pretense of offering more than an intelligent sifting of contemporary imagery, which, upon examination, can reveal much about contemporary life and our implicit ideologies concerning motherhood.

Wynn Bullock once observed that photographs peer at life and attempt to record it truthfully, but can only transcribe two of the four of life’s dimensions. Reduced to the plane of two dimensions on a flat piece of paper, constrained (usually) within the four straight edges of a rectangle, photographs lack two crucial factors: the sense of ongoing time in the three physical dimensions, and the unseen (because unseeable) fourth dimension Bullock called “spirit.”

Even if they could encompass all the dimensions experienced by living human beings, photographs offer complexities of meanings, not single, precisely definable and verifiable meanings. Like value of any kind, meaning is ascribed by the viewer, the person examining the image in his or her own specific moment of time. We decode a picture the only way we can: through our visual enculturation, interpreting images by means of our idiosyncratic backgrounds as well, including socio-economic class, political bias, educational level, religious affiliation or spiritual inclination, competence with symbolism and other aspects of iconography, and a multitude of other vital influences. Of these, perhaps none is more important than how we relate to our own status and history in the hierarchy of family relationships.

What is remarkable, then, is that creative photographers manage to convey a great deal about reality, about life, about the spirit of human beings, and about superordinate realities sometimes called the Zeitgeist, or the Soul of an Era. Photographs, which always require close study and attention before their various potential meanings can reveal themselves, can and do provide a substantial number of clues about relationships. We simply have to be tuned in to those clues and to have both patience and humility in assigning their significance. While verbal information often proves crucially useful in this enterprise, it is not always as helpful as we might suspect.

Perhaps surprisingly, the most explicit caption may fail to explain the specifics of either a relationship or a situation depicted in a single photograph. Consider, for example, the Matthew Brady albumen print which the Library of Congress identified as Rose O’Neal Greenhow with her daughter in the courtyard of the Old Capitol Prison, Washington, D.C. (page 99, left) The caption for this 1865 picture seems explicit enough, yet it tells us nothing about the fact that Rose Greenhow was a Confederate spy captured by Union forces. That fact explains why she was photographed in the courtyard of a prison, but does not explain the presence of her daughter, who clutches her tightlipped mother with a strong, protective embrace. Are they about to be separated? Is the mother about to be hanged? How did Rose Greenhow manage to maintain her elegant costume, her dainty gloves, her air of nobility? Without a considerable amount of biographical research, we may never know what, exactly, is being depicted here. Yet perhaps we can manage to decipher the mood of strained affection and taint of sorrow. We can do this because we tend to believe that emotions reveal themselves through the face, body posture, gestures of hands, just as we interpret the historical moment and social cHss of persons through their apparel.

American audiences and American photographers of the mid-nineteenth century cared much more for facts than for the melodrama of an “art” picture by the British photographer Henry Peach Robinson. Fading Away (page 99, right) is obviously a fiction, a tableau, so we do not expect realistic documentation, but try to interpret the symbols provided by this 1858 concoction. Watched over by an older sister (or perhaps a good friend), a young woman fades away to die amid the mawkish trappings of a scene that could have come straight out of Dickens. The bonneted mother seems resigned to her child’s fate; she holds a book, undoubtedly moral teachings about accepting death. Compiled from a number of separate negatives, Fading Away, with its powerful symmetry, artificial poses, and distraught male figure (the father? a husband?) bids us all too dramatically to weep. The bright sky, however, offers hope of heaven: the daughter will soon be among the angels. Too reminiscent of theater to be taken seriously today, the picture tells little about the grief of the mother. From a knowledge of Victorian conventions, we know that the mother was taught Christian resignation, and to express grief most genteelly, without the rending of clothes, wailing, and uncontrollable anguish that might emanate from other ethnic groups. We should also take note that it was all too common in the mid-nineteenth century for mothers to lose their daughters (and sons) to the ravages of tuberculosis, pneumonia, or typhoid fever.

America’s greatest portrayer of the mother-daughter relationship in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was indisputably Gertrude Käsebier. In her justly famous photograph, Blessed Art Thou Among Women (page 100, left), an elegant mother seems to be urging her adored daughter to cross the threshold, a metaphor for entering adult life, and to pass confidently from one state of being to another. The lovely formal aspects of this 1899 gum platinum print were the result of Käsebier’s expert posterization, a technique that emanated from both the teachings of Arthur Wesley Dow and japonisme in artistic posters themselves. The decorative darks concentrated in the figure of the daughter, with her precise contour, are enhanced by contrast to the wraithlike whiteness of the mother, a woman who by her overtly, loving connection with the daughter epitomized what mothers were supposed to be. It was, as the author and critic Ann Dally has remarked, the era that “invented motherhood” as a relationship of an almost suffocating closeness between the maternal figure and the offspring. Yet Käsebier displays that intimacy not as suffocating, but as sublimely supportive.

Nothing here presages the imminent death of this beautiful child. These were real people, not the stagey characters of Fading Away. The pair were Käsebier’s friend, Frances Lee, and her daughter. In a later Käsebier photograph of 1900, called The Heritage of Motherhood (page 100, right), Frances Lee was transfigured into a universal symbol of grieving motherhood, with her agony undiminished by the false piety and repressed resignation of the Robinson pastiche. Käsebier took her subject seriously. She was one of the first photographers who rendered the mother-daughter relationship without tear-jerking sentimentality. She granted both female roles respect and admiration, a remarkable accomplishment at a time when to be considered “blessed among women” because one had a daughter was possibly a rare proposition in an American culture that worshipped male progeny. (If women were still on a pedestal in 1900, it was because in that rather awkward position they were hardly able to compete with men for power or even the dignity of the vote.)

The poet Adrienne Rich encapsulated the problem: how we dwelt in two worlds / the daughters and the mothers / in the kingdom of the sons. Iconographically, the worship of a son rather than a daughter has been one of the most enduring and influential images in Western art since the establishment of the Virgin Mary as a primary figure of worship. In our unconscious responses to images of mothers with children, it would be difficult to ignore the residue of all the thousands of reproductions we have seen of paintings showing the Virgin Mother and her God-son. That is perhaps why Lewis Hine’s Ellis Island Madonna (page 101, left) seems strained and falsely titled. The immigrant mother’s adoration is appropriate for the traditional idea of a Madonna, but the daughter she holds so firmly gazes upward with a most peculiar stare, and not at the mother, who is behind the child. Taken with the explosive light of flash powder, the picture surprises because the child did not wince. Flash powder was fast, but tended to make nervous wrecks out of unsuspecting subjects. That a mother was holding a child seems an insufficient excuse to dignify this picture with the resonance of one of the greatest themes of Christian art. Besides, it should have been obvious to Hine that no Madonna had ever worshipped God immanent in a girl-child.

Social class as well as physical presence are two clues to the beauty and charm of James Van der Zee’s portrait of a mother with two daughters. Against a typical studio backdrop of the 1930s, the trio radiates a quiet beauty (page 101, right). The grace and poise of these female members of the black bourgeoisie were heightened by the self-aware prettiness of the little girl who has wrapped her mother in two arms. Not quite so adorable, the other daughter is more relaxed. The mother could easily have posed for Raphael, and the group is the visual antithesis of the farm wife with children so typical of the work of Michael Disfarmer (page 102, left).

In a frontal pose that bluntly presents an enraged daughter and a gently resigned mother, this Disfarmer studio portrait is completely bare of environmental or fictional ambience, a technique that Richard Avedon adopted for its ability to concentrate total attention on the participants in a photograph. The mother’s willingness to be recorded in her gaudy cheap dress and anklets with sandals indicates not a lack of aesthetic taste but of education, and deep poverty. The mother restrains her glaring daughter with a protective hand that has known labor. For the sake of historical accuracy, it should be noted that it is sometimes impossible to distinguish very young girls from boys because in many areas it was customary for both to wear dresses in infancy. But this sturdy youngster seems unquestionably a girl.

In another Disfarmer double portrait (page 102, right), one which features a wonderful rhythm of diagonally placed forearms and vertical legs, a rural mother perches with her teenage daughter in an affectionate and casual pose. The young girl is comfortable, relaxed, and intelligent, and her mother, looking away from the camera, seems as solid and strong as our stereotype of farm wives and pioneer women would have us believe. No resignation, no anger here; these are straightforward people, so real one feels able to strike up a conversation as soon as they stop posing. If farm life was hard in the thirties and forties, nothing in this Disfarmer image reminds us of the terrifying Great Depression that echoes so implacably in the work of Dorothea Lange.

Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California, 1936 (page 103) is Lange’s most famous picture, one that is almost an embarrassment to reproduce yet another time, as the concerned mother survived the dust bowl agony to tell the world that she had never received a penny for the thousands of times this picture has been printed. Certainly, she was immortalized as the very essence of the infinite cares of motherhood. How to feed, clean, clothe these daughters in the midst of social disintegration? How to summon the strength to go on working as a grossly underpaid pea-picker in the hell of a California migrant camp? How to maintain the unity of this desperate family? What would be the future of these starving daughters without the opportunity of an education? Would the father be able to find work? The Lange image, so sculptural and sure in its details, makes a direct impact on the emotions, reminding us of the anguish of extreme poverty before it invites us to ask questions about the fate of individuals confronted by social disaster.

While the Farm Security Administration photographers were out scouting for pictures that they hoped would arouse the sympathy of an America distracted by nationwide unemployment, even more dangerous threats were brewing in Europe and the Far East. World War II—that last “good” war where the alternatives to defeating Hitler’s Germany were nonexistent—hurled destruction on millions of innocent civilians. After the war, Americans turned to “togetherness” and family life with considerable enthusiasm. In Eve Arnold’s interior scene (page 104), we find a sailor home on leave, his wife continuing the middle-class niceties of white gloves for the dainty blonde daughter. The youngest plays happily with the Sunday funnies, oblivious both to the socialization process being inflicted on her sister and to the meaning of her father’s uniform. Perhaps the older daughter is being readied for Sunday school, or the family has just returned from an early visit to church (the clock reads 10:55 and the light indicates that this is morning). The history of the movies tells us that the dolled-up child has been coiffed and dressed in imitation of that great culture icon of the 1930’s, Shirley Temple, whose singing, dancing, and unbridled cuteness won the hearts of many a mother. The artless accoutrements of the room include an early television set (television did not become ubiquitous until the 1950’s), which, marvelously, mirrors back the daughter who is already the mirror of a cultural ideal. That the mother should be the transmitter of this ideal is obvious; less obvious, perhaps, is that the daughter is without the power to choose an alternative vision of female childhood. Meanwhile, the young father buries himself in “man’s work,” reading the sports pages or the political news. Ordinary women were not expected to be interested in politics.

One of the most poignant mother-daughter images of the late 1940 s was taken by Jerome Liebling at a Jewish wedding in Brooklyn (page 105). Here, side by side, viewed with Liebling’s characteristic combination of brutal honesty and compassion, are two generations. It has been said that a man can tell the future of his intended bride by looking at the face and figure of his intended mother-in-law. Will this sensual daughter indeed grow to resemble the monumental mother? Together, they offer a visual contrast as stark as that between the delicacy of a Tanagra figurine and the baroque extravagance of late Hellenistic sculpture.

In the diary of Anaïs Nin, she describes her mother in terms that illuminate Liebling’s portrait: “She was secretive about sex, yet florid, natural, warm, fond of eating, earthy in other ways. But she became a Mother, sexless, all maternity, a devouring maternity enveloping us; heroic, yes, battling for her children, working, sacrificing. ” This concept, of the Mother becoming somehow sexless, has been challenged by some writers, including Nancy Friday. Yet many daughters would prefer the stalwart Liebling mother to the mod mother portrayed by Linda Brooks in her 1981 picture entitled Mom at 55, me nearing 30 (page 28). “Mom” is flirting with the camera, offering herself as strong competition to her daughter. “Mom” is also a social butterfly: can we ignore the butterfly motif on plants and in petit point? The Linda Brooks picture, like so many others in this collection, can be read as a painful reminder of the perils inherent in the mother-daughter relationship. If ”Mom” is always outcharming the daughter, constantly demonstrating how youthful she is, how much prettier she is, then she cannot be used as a role model. She becomes the devouring Gorgon of a daughter’s nightmares, the enemy who is always victorious, the diminisher of one’s hopes, the inflicter of a permanently damaged self-respect.

How different is the reverse of the problem! In Joel Meyerowitz’s splendid portrait of an upper-class mother and daughter seen in the pastel light of an early evening on Cape Cod, it is the daughter rather than the mother who flirts with the photographer (page 11). What are the clues to their social class? It seems that it is only lower middle-class women and the jet set who bother to create fantastic bouffant coiffures. Intellectuals and old money disguise themselves, or simply do not care. Then there are the rings on the mother’s hands, the casual but stunning white trousers, the Wasp features, her stance. The daughter, who seems accustomed to being admired, is carefully making a display of herself as elegant as any Botticelli. This is no candid shot taken with a 35mm autofocus, but a deliberate posing for an 8 x 10 view camera. These are two women who are presenting their personae more as individuals than as connected in a relationship: the mother’s arm crosses behind the girl, but by no stretch of the imagination can this be considered an embrace.

Sexuality haunts all mother-daughter relationships. Daughters may be wonderful creatures, but their chastity must be protected. They must be safely married off. In a surreal moment captured by Sage Sohier at a Utah picnic (page 38), the sexuality of the daughter is overwhelming. Zaftig in her tight shorts, her blonde hair askew as if it were mirroring an inner wish for freedom from constraint, she holds—yes!—an apple to her mouth. Was there a satanic serpent in that tree? Eve: the eternal seductress, the first sinner, our first mother (unless you count Mother Earth, Lilith, or Pandora), who was called “The Mother of all Living Things,” has also been defended by skillful exegesis of the book of Genesis, where, curiously enough, there are two versions of her creation. In the first, God creates male and female as equals; in the second, Eve is notoriously Adam’s Rib. Apple to mouth, Sohier’s young woman is a pictorial equivalent to that Eve who ate the fruit out of primordial disobedience,‘and who thereupon brought the knowledge of sexuality into the world. In that act, too, she cast herself not only into demeaning bondage to the male, but was cursed with having to bring forth children in dire pain. This story of the origins of male/female relationships and of the presence of evil has powerfully influenced attitudes even today, and still surfaces in the iconography of women.

Sexuality does indeed haunt all family relationships, even when the sexuality of the parents has been channeled into reproduction, as we see in Sally Mann’s Jenny and Her Mother (page 25). An adolescent daughter clings to her pregnant mother, who leans against one of the symbols of womanhood: the washing machine. Why such sorrow in the daughter’s face? Thirteen, perhaps, she is all too conscious of the genesis of that baby-to-be. Needy still, as are all adolescents who perch so precariously between the safety of childhood and the perils of young adulthood, she intertwines her body with her mother’s. It is as if the daughter is drowning and is hanging on for dear life, while the mother, accustomed to the emotional demands of the child, strives to keep her head up, as if she is afraid of being sucked down by the child. Any excessively symbiotic relationship between mothers and daughters is threatening to each, for each needs to preserve her own identity and separateness. The Mann portrait is a marvelous display of the passion of the quintessential female-to-female arc.

Mothers are our first teachers, and it is they who decide what shall be our first lessons. Todd Merrill’s Susan and Blaze (page 87) brings us into a contemporary middle-class kitchen. A young, attractive mother, her waist bound with a short red apron, is introducing her gap-toothed daughter to the single most important function of women in any family: the provision of food. The girl is happy, excited; the mother pulls her daughter’s head close, in a gesture that could smother the child. Together they make pizza. The girl is learning how to prepare the appetizing food that Daddy will enjoy with them when he comes home. It can be noted that most food advertising on television and in the popular magazines tends to equate food with love, with mother love in particular, as well as with sensuous pleasure. Mother, of course, cannot escape being equated with food: she is food, was our first food. As every marketing consultant for food companies knows, Mother is not only the vessel in which the fetus grows but also the vessel out of which food miraculously appears for the infant.

Some mothers do not necessarily concentrate on teaching their daughters how to cook or even how to become motherly. Some, as in Susan Copen-Oken’s devastating photograph called Coach (page 73) are preparing their daughters to perform, to compete, perhaps for Miss America, perhaps for the musical comedy stage. Only someone who has ambitions to be on the stage herself would be able to teach her daughter how to mimic the desired gestures and poses. It seems natural enough for a parent to want to create a child in his or her own image. In Mommie Dearest, the scalding autobiography of Joan Crawford’s daughter, Christina, there is a photograph of them together when Christina was perhaps four years old. They are dressed exactly alike, in an awfully folksy item of the fifties, dirndle jumpers over puffed-sleeve white blouses. Mother Joan, then a famous actress and glamour girl, obviously outshines the grinning tot. There is a hypothesis that women who create these performances of dressing alike were probably extremely frustrated in their relationships with their own mothers, and seek a close relationship with their daughters as compensation, also believing they will gain in youthfulness by such tactics as dressing their daughters in miniature versions of their own clothes.

Dressing alike may seem like fun to some daughters, but others want to keep their mothers from imitating their activities. Such a pair can be studied in Margaret Randall’s Mother and Daughter Riding (page 79). It is impossible to guess whether it was the daughter or the mother who initiated this biking form of togetherness, yet the clue of the daughter’s expression indicates that she would just as soon not be compared with her mother or to share the fun with the older woman, who seems to be having such a grand time. Each generation needs to find itself through generationally exclusive activities, language, clothing, and hair styles. To be too closely identified with the mother is viewed as not being “cool.” Besides, the point of generationally exclusive behavior is to make separation from the parent possible—being a pal is not the same as being a Mom.

Sometimes a photographer has the good fortune to encapsulate the entire history of a relationship in a single picture. Carla Weber’s acerbic Donna and Diane (page 50) reveals much more than the typical middle-class delight in portraiture. The pictures of daughter Diane, growing up blonde and once quite pretty, guard both sides of a mirror in which today’s realities can be seen. The mother is forceful, with the beady eyes and jutting-forward gesture of her chin that makes her resemble a bird of prey. The daughter seems repressed, subdued, even close to depression. It is possible to read a failed life in the daughter’s expression, and a wariness like a caged animal. These two are overwhelmed by the objects in the mother’s house. One longs to say to these women: at least hold hands, look at each other, relate to each other, let the mother give the daughter the assurance that she need not live up to those banal portraits behind her.

After the airless claustrophobia of the Carla Weber portrait, turning to Milton Rogovin’s dual image of an Appalachian woman and her daughter is a relief (page 84). Here is a woman who has had the courage to enter what has been traditionally a man’s job: mining. Recent history tells us that she will have undergone a painful initiation, including rejection by her male coworkers, then perhaps a grudging respect. This woman is earning far more at a dangerous, grimy job than she might as a clerk in a local department store. Despite having entered a masculine province, when she washes up and sits in her living room embracing her reluctant daughter, she clearly retains her femininity. She even stresses the conventionality of her femaleness, if you accept as a clue the customary southern-belle doll atop the radio. Visible pride is here, and a comfortable affection for the child, but unfortunately the photographer can tell us little about the child except her recalcitrance at being photographed. We can guess that she may be one of those children who hates being hugged by her parents in front of strangers.

Paul Fusco’s Cocopah Indian Family (page 61) is a revelation of another kind. The pain of poverty seems to have been overcome by a strongly loving connection. In what was apparently a grab shot, Fusco recorded a lively truth: the boys will be independent of their mother’s affections far sooner than the girl will be. How very easy they are with each other, this mother and her pretty daughter, the boys, meanwhile, are roughhousing, learning how to be men as they might understand the meaning of that role. When a photographer has been completely accepted by a family, when they become oblivious to his or her presence, forgetting the clicking of the shutter, wonderfully truthful and intimate insights can be gleaned.

One of the great masters of this kind of insight, Garry Winogrand, gives us a glimpse of an eternal verity (page 107) with his picture of a young mother with one child in a shoulder carrier and her daughter embracing her hand with an expression of total adoration. Watching her step on the often potholed pavements of Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue, the mother seems somewhat abstracted, yet she is not aloof. She holds the girl’s hand firmly, protectively. It is easy to imagine this mother and this daughter sharing a story over milk and cookies, or reading aloud together from a book before the girl goes to sleep. So many photographs of mothers and daughters, from the time of Gertrude Käsebier to the present, display them in this storybook relationship. Alice Walker, author of The Color Purple, wrote about her own mother’s stories as the most precious cargo of her soul. It was not only that she would retell them, but that she believed her mother was a writer manqué. What was more important, claimed Walker, was the fact that she absorbed the cadences of her mother’s voice until they became part of her own art. Even though the Winogrand photograph does not show a mother reading to a child, something about the daughters’ almost convulsive gesture of love bespeaks a close, articulate friendship between the two.

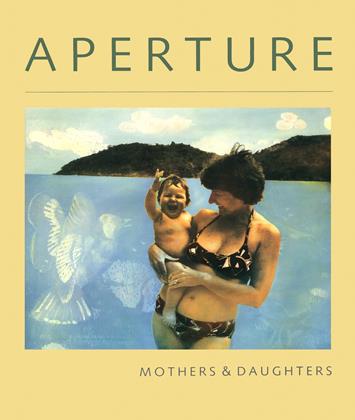

Perhaps the most joyous photograph in the entire collection is Bea Nettles’ Rachel and the Bananaquit (front cover). Bea has undoubtedly been telling her merry daughter about a fantastic bird, a story that Rachel will remember and can recall as long as this picture survives. Here is the mother-daughter combination before the pressures of growing up intervene, before competition emerges, before sexuality threatens, before illness or separation or divorce or social disaster can overpower this captivating joie de vivre. It is perhaps the single picture in the collection that is a genuine Adoration, with the daughter even raising her chubby little hand as if in benediction. It is an incredibly rich image despite its pictorial directness and simplicity.

Could the Nettles’ picture have had the same effect in black and white? No. An immediate loss would be the warm interaction between flesh tones, fantasy creature, and tropical landscape. Yet many photographers contend that nothing but black and white can express concepts. Robert Frank, for one, once insisted that black and white were the only possible colors for photographs. He wrote that they symbolized the antipodes of hope and despair to which humanity was forever doomed. His was a tragic vision, yet not all photographers choose to see the world in such radically opposed values. Even Frank admitted, “There is one thing the photograph must contain, the humanity of the moment.” If several of the photographs in this collection hint at despair, many of them, like the Nettles picture, do indeed reverberate with the humanity of the moment, humanity here meaning not simply people, but their humaneness, their tenderness, their loving, their fragilities, their strengths.

Since our humanity can be expressed in both verbal and visual languages, it can be said that Mother is a verb, while Daughter can be nothing but a noun. To mother is to nurture, to cherish, to nurse, to care for, to encourage, to provide sustenance for, to educate: those are the good attributes of our verb. The less admirable attributes are still verbs: to dominate, to squelch, to crush, to compete, to smother—yet these are not ordinarily considered the exclusive behaviors of the role of Mother, but merely the unsavory behaviors of human beings, male or female. To daughter does not exist as a verb; one cannot “daughter” someone else, whereas one can “mother” even if you are male.

This difference in the syntactical definitions of their roles accounts for the absence of some types of interactions from this collection. We do not, for example, see many older daughters caring for their invalid mothers. We do not see—and how to represent it?—mature women taking on the reversed roles of mothering the mother in her old age. We do, however, see glimpses of the generations of great grandmother, grandmother, mother, and daughter, with the daughter sometimes bearing in her arms the succeeding generation. This chain of being, female to female, has been the inspiration for much contemporary literature and poetry, and, to judge by these photographs, has become the focus of attention for many visual artists as well. The struggle is to convey through concrete physical appearance the ineffable, the indescribable subtleties of a primary female relationship.

That relationship between mothers and daughters has undergone many changes. While every mother in the past was perforce also a daughter, today’s options ensure that not every daughter may choose to be a mother. It was perhaps inevitable that sophisticated technology, birth control methods that are relatively safe, a complete alteration in the nature of work and other socioeconomic factors of the postindustrial world, would impinge on the structure of the family. It was inevitable that the division of labor eminently suited to the cave-hunter stage of society—with women safely indoors bearing and rearing children, and men outdoors hunting the woolly mammoth for food—would alter not only with the advent of agriculture and the domestication of animals but also with the long history of a shift from production to service. The complexities of cities, the long commutes to work, the recent struggle for the father to share the responsibilities of parenthood, the ever-rising rate of divorce and the subsequent abandonment of women to poverty-stricken single parenthood—all these factors will impact on what might otherwise seem to be the most natural and fundamental of all relationships, that of mother to child. Even the privilege of educating the daughters may be shifted elsewhere.

Photographers will need to be able to communicate these subtleties without reviving traditional stereotypes. So much is invisible in any relationship that it requires great feats of the imagination to conjure up significant meanings that we can share. We are still learning about the varieties of motherdaughter interactions, just as we are beginning to learn about many other aspects of what it means to be human. These pictures demonstrate that there is no single mother-daughter relationship, but almost as many differences as there are individuals.

THE ENVELOPE

It is true, Martin Heidegger, as you have written, I fear to cease, even knowing that at the hour of my death my daughters will absorb me, even knowing they will carry me about forever inside them, an arrested fetus, even as I carry the ghost of my mother under my navel, a nervy little androgynous person, a miracle folded in lotus position.

Like those old pear-shaped Russian dolls that open at the middle to reveal another and another, down to the peasized, irreducible minim, may we carry our mothers forth in our bellies. May we, borne onward by our daughters, ride in the Envelope of Almost-lnfinity, that chain letter good for the next twenty-five thousand days of their lives.

MAXINE KUMIN