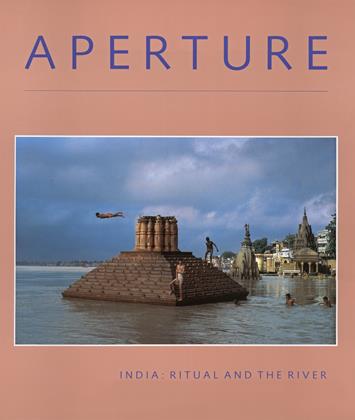

Ritual and the River

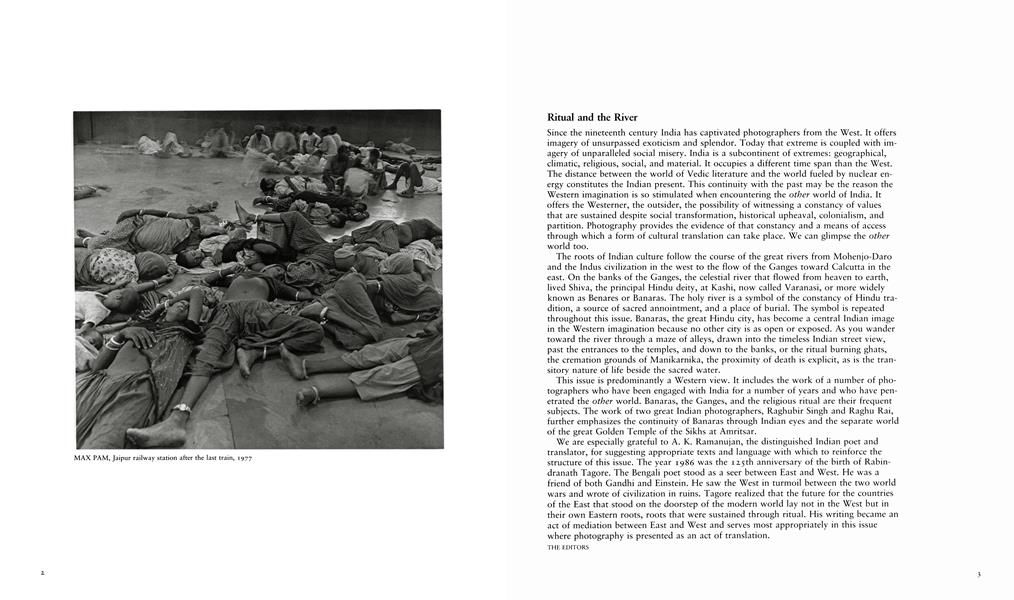

Since the nineteenth century India has captivated photographers from the West. It offers imagery of unsurpassed exoticism and splendor. Today that extreme is coupled with imagery of unparalleled social misery. India is a subcontinent of extremes: geographical, climatic, religious, social, and material. It occupies a different time span than the West. The distance between the world of Vedic literature and the world fueled by nuclear energy constitutes the Indian present. This continuity with the past may be the reason the Western imagination is so stimulated when encountering the other world of India. It offers the Westerner, the outsider, the possibility of witnessing a constancy of values that are sustained despite social transformation, historical upheaval, colonialism, and partition. Photography provides the evidence of that constancy and a means of access through which a form of cultural translation can take place. We can glimpse the other world too.

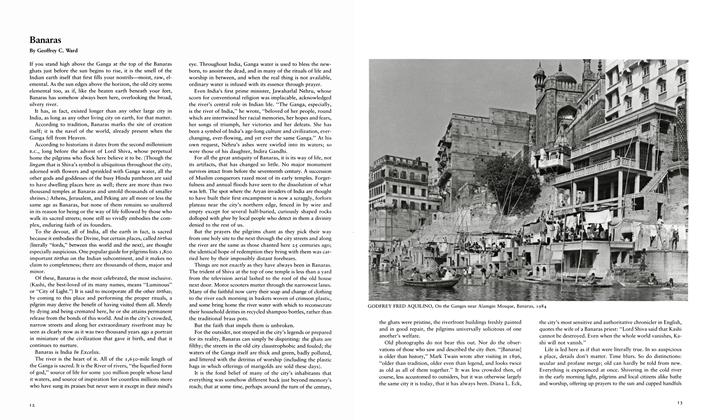

The roots of Indian culture follow the course of the great rivers from Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus civilization in the west to the flow of the Ganges toward Calcutta in the east. On the banks of the Ganges, the celestial river that flowed from heaven to earth, lived Shiva, the principal Hindu deity, at Kashi, now called Varanasi, or more widely known as Benares or Bañaras. The holy river is a symbol of the constancy of Hindu tradition, a source of sacred annointment, and a place of burial. The symbol is repeated throughout this issue. Bañaras, the great Hindu city, has become a central Indian image in the Western imagination because no other city is as open or exposed. As you wander toward the river through a maze of alleys, drawn into the timeless Indian street view, past the entrances to the temples, and down to the banks, or the ritual burning ghats, the cremation grounds of Manikarnika, the proximity of death is explicit, as is the transitory nature of life beside the sacred water.

This issue is predominantly a Western view. It includes the work of a number of photographers who have been engaged with India for a number of years and who have penetrated the other world. Bañaras, the Ganges, and the religious ritual are their frequent subjects. The work of two great Indian photographers, Raghubir Singh and Raghu Rai, further emphasizes the continuity of Bañaras through Indian eyes and the separate world of the great Golden Temple of the Sikhs at Amritsar.

We are especially grateful to A. K. Ramanujan, the distinguished Indian poet and translator, for suggesting appropriate texts and language with which to reinforce the structure of this issue. The year 1986 was the 12.5th anniversary of the birth of Rabindranath Tagore. The Bengali poet stood as a seer between East and West. He was a friend of both Gandhi and Einstein. He saw the West in turmoil between the two world wars and wrote of civilization in ruins. Tagore realized that the future for the countries of the East that stood on the doorstep of the modern world lay not in the West but in their own Eastern roots, roots that were sustained through ritual. His writing became an act of mediation between East and West and serves most appropriately in this issue where photography is presented as an act of translation.

THE EDITORS

I love India, not because I cultivate the idolatry of geography, not because I have had the chance to be born in her soil, but because she has saved through the tumultuous ages the living words that have issued from the illuminated consciousness of he great sons: Brahma is truth, Brahma is wisdom, Brahma is infinite; peace is in Brahma, goodness is in Brahma, and the unity of all beings is in Brahma.

RABINDRANATH TAGORE, A Vision of India’s History, 1912

India is of course infinitely more in the imagination than a subject for the photographer; it embodies an entire huge ethos, a symbol for the very ambiguity of human acculturated existence, a testament to the co-existing spiritual grace and emotional disease in all of us. India is as much about human culture per se as it is about mans relation to nature. JANE LIVINGSTON

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

The Editors

-

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteTechnology And Transformation

Spring 1987 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

Editor's NotePhotostroika: New Soviet Photography

Fall 1989 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteMoments Of Grace: Spirit In The American Landscape

Winter 1998 By The Editors -

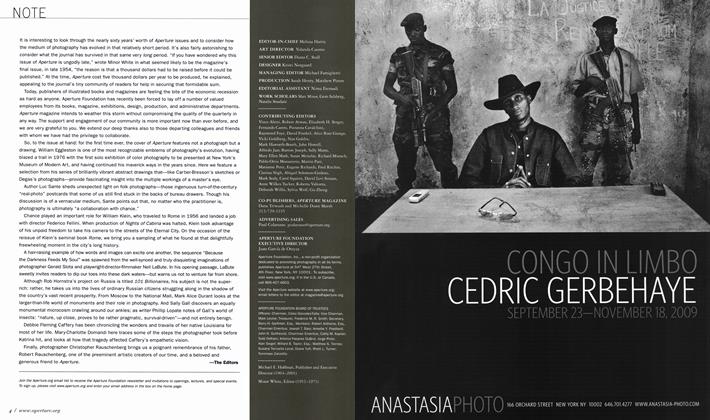

Note

NoteNote

Fall 2009 By The Editors -

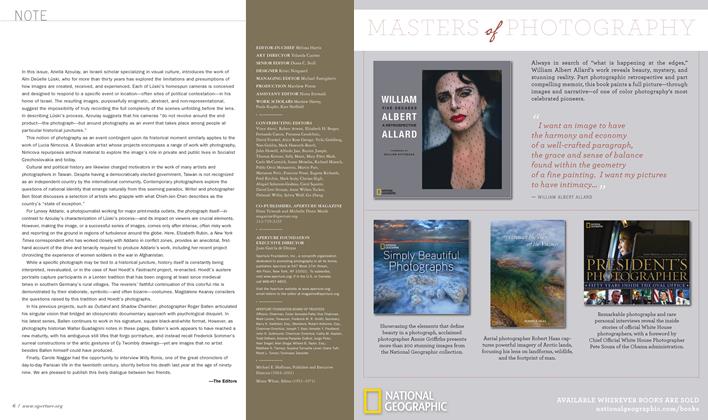

Note

NoteNote

Winter 2010 By The Editors -

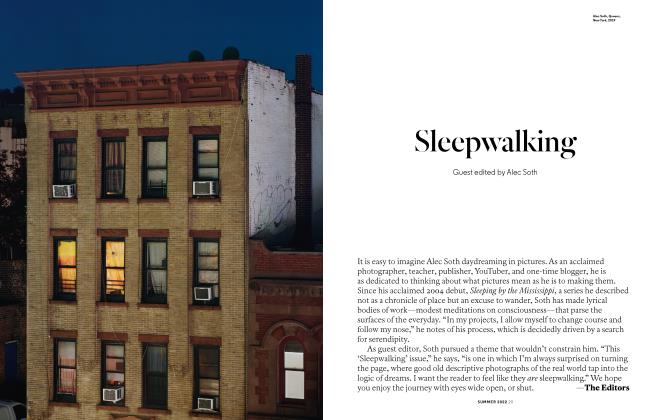

Sleepwalking

SUMMER 2022 By The Editors