THE SPECULATIVE OR SECRET ART

There is only one way in which symbols may be made truly living. One by one material things come to be known for what they are, beautiful symbols of still more beautiful Realities. One by one they are taken into the mind and their outward forms transcended until in the end only the Realities themselves are contemplated, and at last the soul comes to behold the One Reality face to face, and symbolism is overpassed.—Alvin Langdon Coburn70

In October 1912 Coburn married Edith Wightman Clement of Boston in Trinity Church, New York.

At this period I was far from well. How my wife (bless her) had the courage to marry me I often wonder, but she did.71

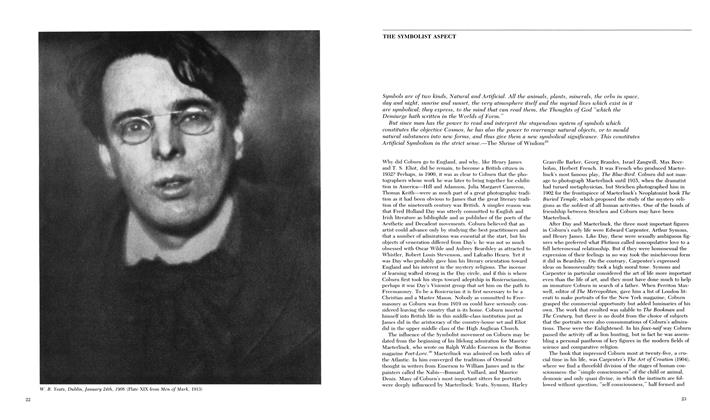

In an important sense this step marked the end of Coburn's photographic career. There were portraits to take, Vortographs to make, and Harlech and early British sites like Avebury to photograph, but marriage betokened psychological change. Rebellious youth gave way, at thirty, to the quieting of ambition in the wise care of a new maternal figure whom Coburn was now ready to accept. The next years until 1916 were spent producing books from work done almost ten years before, like Men of Mark and Moor Park, and organizing and making prints for his “Old Masters of Photography” exhibition, which toured the United States.

In 1916 Coburn was invited to Harlech by George Davison, whose great career in photography was now also finished. Davison occupied himself with the sponsorship of several groups making ways of life alternative to those of the establishment. He was seriously involved in the Labour movement, encouraged post-Symbolist music, and was host to a group concerned with comparative religious studies.72 Cyril Scott and Sir Granville Bantock were two leading British composers in Davison’s circle who shared Coburn’s religious interests. Scott was a Theosophist of the Blavatskian school, but Coburn found this ecstatic path to wisdom ultimately too disquieting for himself. Although he and Scott were students of the occult together in 1916, when Coburn in 1923 finally found a road that satisfied him he looked back on those experimental years as a waste of time. He had even fallen for the idea of astrological portraiture, unlike David Octavius Hill when invited to consider the possibility of phrenological portraiture in the 1840s.

These follies ended when Coburn met the man who put him on the quietist path to wisdom. Through him Coburn joined the Universal Order, which dedicated itself to the study of sacred texts referred to collectively as The Shrine of Wisdom, which was also the title of the magazine issued by the group.73 The group was intended to be not a popular religious movement but an anonymous society, and its magazine and other publications remain available today to those who want to broaden their religious knowledge without abandoning their own beliefs. Its explanatory leaflets explicitly reject spiritualism, occultism, astralism, magic, and parapsychology:

The inordinate craving for the mysterious and extraordinary is a perversion of the soul’s natural desire for the beautiful; because the more real mystery there is in a work of art the more intrinsic is the beauty that it holds.74

The emphasis is on devotional meditation on texts drawn from the great mystic traditions of the world: Hermetic (Hermes Trismegistus), Greek (Pythagoras and Plato), Neoplatonic (Plotinus and Thomas Taylor), Christian Neoplatonic (Dionysius the Areopagite and St. Paul), Chinese (Lao-tzu), Indian (the Gita), and Buddhist (the Mahayana school). That Coburn knew all these texts extremely well is certain. That he was one of the editors of the Shrine of Wisdom magazine seems extremely likely.

A close reading of Coburn’s commentary to The Classic of Purity, attributed both to Lao-tzu and to Ko-hsuan, shows how committed to Taoism he was, but also how he was able to relate its tenets to those of the Mahayana school on the one hand and those of Dionysius the Areopagite on the other.

Basically, there are two ways of approaching God, that of the Via Affirmativa, in which the mind is concerned with what He is, in relation to that which the finite is not, and that of the Via Negativa, which denies of Him all finite limitations or attributes whatsover.75

If we engage with Coburn’s distinction and analogize this in terms of photography, the difference is between bringing a consciousness of universals to certain particulars in the visible world (the photographic affirmative or positive) and stripping away the external aspect of all particulars until universals are revealed (the photographic negative). The positive demands a strong idealizing principle to order it. The negative is an aid to abstraction because it inverts and reverses spatial organization and tonal relationships. The positive way requires knowledge of a preexistent order; the negative way stimulates discovery of such a pattern. Arthur Symons put it differently:

All mystics being concerned with what is divine in life, with the laws which apply equally to time and eternity, it may happen to one to concern himself chiefly with time seen under the aspect of eternity, to another to concern himself with eternity under the aspect of time.76

The temporal emphasis is realist or positive in tendency, the eternal emphasis idealist or negative. But they are, as Coburn explained, complementary:

The Via Affirmativa and the Via Negativa have also been termed two modes of Contemplation of the Divine; they are said to mark the equilibrating Pulse of the true Mystical Life.

The approach to the Light Unapproachable is as much the goal for the mystic as the Inexpressible Meaning is for the Symbolist. But it is not a matter merely of intellect; it requires intuition and feeling trained and enhanced by quieting the desires. Coburn rejected the idea of mystical experiences induced by drugs, saying that he would rather “come in by the front door” or not at all.77

Coburn s commentary on the Yin Fu King of the emperor Huang-ti further confirms his position:

The wise may sometimes appear to be foolish and the foolish to be wise. But in apparent foolishness profound wisdom may be expressed and in apparent wisdom, great foolishness.78

Coburn’s own autobiography appears to be an extraordinarily naïve document, but it is only as “foolish” as the Masonic writings are “wise.” He had arrived at a stage when he regarded self-importance as nothing compared with Tao. The years of ambition, competition, egocentricity, and unnamed desires were past, but the wish to be remembered publicly for his photographs was not entirely stilled:

The Soul of man loves purity, but his mind is often rebellious. The mind of man loves stillness, but his desires draw him into activity. When a man is constantly able to govern his desires, his mind becomes spontaneously still.79

What had gradually happened was that the expression of Coburn’s true nature had shifted its ground. Up to the age of thirty he was a photographer-priest, as Sesshü was an artist-priest. From the time of his marriage he became increasingly a priestartist like another, later Japanese painter, Sengai. The spiritual channel had been open all along, but when it found its religious outlet Coburn’s photographic career was reduced to a hobby.

The photographs became merely confirmations of what he already knew intellectually. They were no longer the uncertain adventures of his youth but didactic tools. In youth the symbol was as mysteriously real as the truth for which it stood, but in age the descent into allegory and emblem marked the diversion of Coburn’s energies from the operative to the speculative mode.

Like zenga (Buddhist aesthetic objects for meditation), the Edinburgh and London photographs of the period 190.5-9 contain pictorial themes applicable to Buddha-nature although they are embodied in the Judeo-Christian tradition. Consider “Parliament from the River,” the image of the boat on the Thames in front of the Houses of Parliament, which, neo-Gothic in style, evoke the great cathedrals even though they represent only secular power. The Thames is the great flux. The clocktower of Big Ben measures its passing. The spire, the aspiration of eternal truth, annihilates time. Man, anonymous and barely visible at the oars, must guide his soul-ship through the gulf that divides permanence from change.

The dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral offered Coburn several opportunities for such metaphorical constructions. The possibilities of St. Paul’s as a subject were known to others in the Coburn circle of photographers in London. Walter Benington gave it an Impressionist treatment.80 Coburn framed it as if it was a Japanese temple in the manner of Hiroshige, but he also treated it as a Zen landscape and a Masonic emblem. In “St. Paul’s, from Ludgate Circus” the vapor (ch i, breath, air, even matter itself) from a locomotive ascends like a cloud—a manifestation of energy transformed. In the Zen, or Taoist, or Neoplatonic view of things the solid and the evanescent are one. A half dome as the circle of perfection, and a cloud such as a Japanese painter used to balance his space art, were equal in terms of matter and spirit. The cloud is a type form in Coburn, an idealized embodiment of transient effects.81 But as a pictorial motif it should also be related to the flaming clouds in the Pittsburgh steelworks pictures of 1910. In Coburn’s mind, poured steel (“White Hot”) was connected with the power of a waterfall in Yosemite, just as a cosmic flame of molten metal (“The Melting Pot”) was associated with a cloud form. Pillars of smoke and of cumulus cloud were ideally congruent. Like some ancient alchemist, the steelworker intervened in the energy exchange at the operative level.

Behind and within every operative effect, there is a speculative, super-physical or spiritual cause. ... To the Pythagoreans the spiritual significance of a geometrical truth was of far greater importance than its operative use, for from one such idea, innumerable practical examples could be worked . 82 out.

In Freemasonry “operative” and “speculative” are used to distinguish between the practice of the operative craftsmen who built the cathedrals of Europe and the speculative philosophers who developed the idea of God as the Great Architect and Grand Geometrician. Coburn often quoted the definition of Masonry, “A system of morality, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols.” It is a speculative theory of ethics represented to the initiated by means of ritual and emblems drawn from the operative field of classical architecture. Seventeenth-century emblem art was revived in the nineteenth century and even included imagery from the Industrial Revolution. Masonic elements derived from and contributed to this pictorial tradition: arches and bridges, domes and towers, steps and stairways, doorways and portals, fountains and rivers, groves and gardens, and natural and artificial temples, all of which are motifs in Coburn’s work, are found in the emblem books. Moor Park—more a Renaissance palace than an English country house—was a perfect building for photographic treatment as a Masonic memory system.

Freemasonry is deeply established in British public life. It is no exaggeration to say that in Coburn’s time very few prominent members of society were without knowledge of it. The kings of England and the archbishops of Canterbury were all Masons.

Jews were admitted. Freemasonry was and remains a wholly respectable practice:

Freemasonry in the good old easy-going pre-war days may have meant to many, a friendly gathering of brethren meeting for purposes of conviviality, with a background of charity and well-being.83

But Coburn, being American born, took it far more seriously than his new countrymen. To him it was a science of conduct and an art of living, the purpose of which was allegorical and the illustration of which was symbolical,

for we use the operative paraphernalia of the builder s art to indicate the method of an entirely different edifice: a temple not made with hands, the edifice of our own spiritual life.84

Coburn’s London portfolio does not require a specifically Masonic interpretation but may be usefully approached by using a similar system of allegory. For instance, “St. Paul’s, from the River’’ may be read at several levels. Literally, it is a picture of St. Paul’s Cathedral, Waterloo Bridge, and the River Thames. Figuratively, it unites a dome, a bridge, and a river. Allegorically, it offers a dome of knowledge, supported on pillars of Wisdom, over the Great Flood. Anagogically, it shows eternity triumphing over time. In this image, which Coburn used on the cover of the prospectus written by Shaw for the London portfolio, the telephoto lens has so arranged the view that the dome appears to rest on top of the bridge. The strong black line of the balustrade of the bridge separates the Above from the Below in Hermetic terms or in Chinese terms of yang and yin, but “these are in reality always perfectly integrated, for they subsist ideally in the spiritual realms.”85 But in this particular case a Masonic interpretation is probably more apt, because the architect of St. Paul’s, Sir Christopher Wren, was initiated as a Mason in 1691. That Coburn could publish the picture in the Daily Graphic86 shows that such an image could be safely displayed before the public while concealing its true meaning for the initiated.

The Knights Templar lived in the sanctuary of the Middle Temple throughout the fourteenth century, and Coburn photographed the later entrance built by Wren. The associative power of this structure so close to Fountain Court would not have been lost on him. Chivalric orders like that of St. John of Jerusalem and Manichean sects like the Albigenses had recourse to such places of sanctuary and concealment to protect themselves from persecution. But Coburn would have disapproved of the dualism of the Albigenses: to him evil was merely the absence of good, not a reality. If in 1916 Ezra Pound was willing to call Coburn what he would call very few, “Magister,”87 and one of their shared interests was Fenollosa and Eastern thought and another was G. R. S. Mead and Gnostic philosophy, yet another may have been Harold Bayley’s investigations into the lost symbolism of the Albigenses, New Light on the Renaissance (1909) and The Lost Language of Symbolism (1912). If the Templars were an order of chivalry that appealed to Coburn, the Albigenses were an order of education that appealed to Pound. In Avignon these Provençal illuminists expressed in papermarks and woodcuts their secret beliefs, combining Platonism with Christianity in a new intellectural system. The very word “symbol” finds its origin in “password” or “watchword” as well as in secret marks on vases, watermarks in paper, wedding rings, and other tokens. Bayley ended New Light on the Renaissance with a passionate appeal to contemporary artists to continue the secret tradition of the Albigenses:

The Church of the Holy Grail has broken the conditions which once fettered her, but her enemies, though now less material, are still ruthless and malignant. To contend with them successfully, the Church of the Future must cancel the unwarrantable distinction between “secular” and “sacred,” and must re-enlist her old-time emissaries the Musicians, the Dramatists, the Novelists, the Painters, and the Poets.88

Among the symbols that Bayley illustrated were variations on the scale of perfection, or Jacob’s ladder. Coburn himself referred to life as a ladder: “. . . its lowermost extremity rests upon the foundation of the earth, but it ascends even unto heaven.” The development of the soul depended on an ever ascending scale of faculties and power, but the ways of ascent were many.89 The Sphinx at the top of the steps in the photograph “The Sphinx, The Embankment” is the symbol put before a temple by the Egyptians to warn the priests against revealing divine secrets to the profane. “The Steps to the Sir Walter Scott Memorial” lead not to the neo-Gothic monument itself but to a tree, an archetypal motif of Gothic architecture. Another version of the ladder of ascent has, above some steps on Riverside Drive in New York, a viewing point built in Japanese style. Bayley’s versions have at their topmost points a cross, star, or fleur-de-lis, all emblems of Christ. The surmounting elements in Coburn’s designs are spiritual truths symbolized in terms of various religious or mystery systems.

In “The Enchanted Garden” two separate goals are embodied in the same image. On the left a set of steps leads to a figure of Hermes, which typifies the step-by-step approach to the goal; on the right is an illuminated clearing, which typifies the attainment of the goal by the lightning flash of intuition. In China, Northern Zen achieved its goal by the gradual method, whereas Southern Zen preferred sudden enlightenment. In his later life Coburn preferred the wisdom attained by scholarship, but in his photographic career he was more open to ephemeral manifestations in nature. The two methods result in a combination of the monumental with the lyrical. At the foot of the steps is a dark patch symbolic of the invisible presence of the person about to begin the ascent. Masonic emblems often show two figures, one a guide and the other an initiate, standing at the foot of a stairway between two pillars of a porch on the threshold of the initiate’s spiritual ascent.90 At the top of the stairs a Master Mason draws back the veil that conceals the mystery. Coburn did not attempt this kind of allegorical scene with figures, although in the Moor Park photograph “The Edge of the Garden” a silhouetted figure or a fountain, with the ladder motif represented by a low stone projection, may suggest the invisible goal and a token presence.

“Weir’s Close” was singled out by Alfred Stieglitz as especially fine.91 But what did he see in it? Was it the wit of the relation between the light of the sun and man’s feeble imitiation of it, the gaslight? Was it the great arrowhead of light formed by two planes plunging in reverse perspective down right? Did Stieglitz note the significance of the two steps rising to a door in relation to the barred window? This stage set without actors ri vals "Fountain Court" as Coburn's greatest Symbolist picture, an inexpressible combination of sensuous beauty with intellec tual suggestion.

In terms of symbolism the twin towers of "Westminster Ab bey" evoke the Castle-Temple that in the Christian tradition represents the summit of moral achievement and sanctity of life. In combination with the towers, the streetlamps, which contain globe-and-cross forms, typify enlightenment. In "Trafalgar Square" the reflections of the fountain and the column are so related as to evoke the candlestick, which is in all the mystery religions the emblem of good works. This time the invisible presence is the defender of the British Empire, Nelson himself. "The British Lion" is an allegorical picture. Literally, it shows the Victorian artist Sir Edwin Landseer's sculpture together with the cupola of the National Gallery. Figuratively, military power protects the treasure house of civilization. Anagogically, the principle of spiritedness guards the ideal of art: the lion, it had been believed since ancient times, slept with its eyes open.

If London was full of emblematic possibilities, New York may have offered fewer at first sight. Nevertheless, in the photo graph Coburn titled "The Octopus," the shadow of a pinnacle superimposed on part of a series of paths in the form of a wheel may refer obliquely to the idea of the point within the circle.

The Point within a Circle is both a human and a Divine sym bol. With man the point is Spirit and the circumference is body; and the soul, that mystery with its centre everywhere and its circumference nowhere, joins the two.92

Equally, the pinnacle may evoke the dark threat of material power on the white light beneath the solar wheel, which may be either the mark of the learned school of St. Catherine or the excellent wheel of good law. The sun wheel appears as a motif in Coburn's portrait of the photographer George H. Seeley as a Symbolist evocation of this kind. When Coburn used the title "The Octopus" he imagined the creature in the same hiero glyphic context as the lion, the dragon, and the eagle.

A remarkable picture of the Singer Building aspiring vertical ly and the street below running horizontally, making a triangle or V-shape in two planes, with the slightest hint of the displaced Trinity Church at the left edge of the picture, may evoke the branching paths of spirituality and materialism in the modern world. "The Two Trees, Rothenberg" offers a simplified version of a V-shape with the spire of the church rising between the trees. "The Woodland Scene" uses that shape to usher in the moonlight to oppose the darkness. Ezra Pound's image among the Vortographs may be a parody by Coburn of the kind that he made of Mark Twain as an Eastern sage. Pound is divinely fa vored many times over by means of the multiple exposure of his triangular collar points. But the crown of deification that usually accompanied these triangles with twin globes of love and knowl edge-his spectacles-somehow eluded him here, even as it did in life.

If the V-shape of Pound's collar did not stand for spirituality, perhaps it stood for Vorticism, a word that Pound coined to de scribe London's contribution to Cubo-Futurism. Coburn's Vorti cist career lasted all of one month at the beginning of 1917. Under the influence of Ezra Pound—who had been hustling to invent first Imagism and then Vorticism—and having finished his major work and not yet settled in the path of his future life, Coburn tried to find his way into the vortex of literary London. He had made portraits of Wyndham Lewis and Edward Wadsworth that included their Vorticist paintings as backgrounds.93 In Punch magazine there was already in June 1914 a cartoon, “The Cubist Photographer,” in which a large prism was shown set up between camera and sitter, with a series of multifaceted images on the wall of the studio.94

Coburn had helped pay for the publication of Max Weber’s Cubist Poems (1914), and probably took his modernist principles from him rather than Pound. At the Clarence White School of Photography in New York, Weber had encouraged the students to bring as much abstraction as possible into their work. The emphasis was on design rather than representation. Coburn saw these exercises at an exhibition of the Royal Photographic Society in 1915, and some were published in the magazine of the Pictorial Photographers of America, Photo-Graphic Art, for which Coburn was the London correspondent.95 An unsigned article in the same issue cautioned against unthinking and willful overproduction in photography. The young photographer had to decide “whether his presence in photography is to contribute to its advancement or to join those who are conducting an aimless existence.”

The terrors of an aimless existence confronted Coburn. Steichen faced the end of Pictorialist photography by studying art forms in nature and new ideas about proportion. This intelligent decision helped develop the metamorphic tradition that would sustain two generations of American photographers, from Edward Weston to Paul Caponigro.96 It represented a firm commitment to realism in photography. But the idealist tendency in Coburn’s personality was too strong to allow him to make the transition from Pictorialism to straight photography. From the beginning of his career to the very end it is clear that he was progressing down a road to pure idealism. Vorticism represented the moment when he arrived at extreme abstraction in photography.

Steichen had been able to continue because he was able to adjust to new photographic conditions—the new bromide papers, the new objectivity—and find metamorphic meaning in the appearances of nature. Coburn could not. He attempted in the Vortograph to turn his Symbolist approach, already heavily slanted in favor of idealism, into a formula. He no longer allowed the inner forms in nature to interact with its outer aspects but imposed his idealist will on it. If Pound was an idealist posing as a realist, Coburn was never anything other than the complete epopt who dealt in mysteries. Dematerialization or idealization was his aim. While this was restrained by his relation to the Pictorialist tradition, he could work against its conventional aspects to wonderful effect; but when he broke with that tradition, his ideal philosophy turned his work into ciphers of no importance to anyone other than himself. Vorticism marks the moment when he briefly despaired of being able to consider outer phenomena as other than distorted aspects of an ideal geometry. The Vorticists, organized by Pound and Wyndham Lewis, produced an exhibition in June 1915, and two issues of a magazine, Blast, in which, among others, Frank Brangwyn was “blasted” as out of date (in fact, he was at the height of his fame). But the new tyros of the art world were determined to have a movement, like the French, Germans, and Italians, no matter how alien such a concept is to the British, and Coburn had to join or be blasted, too.

Pound contributed an anonymous introduction to Coburn s exhibition “Vortographs and Paintings” at the Camera Club in London in February 1917. Coburn added a postscript in which he expressed his realization that he had been used to further Pound’s movement. The paintings he had made in the summer of 1916, before he had the benefit of the Vortescope—the combination of mirrors that produced the pseudopris matic image of the Vortographs—were Post-Impressionist. They were decorative, artificial in color, yet related to reality, so Pound excluded Coburn from the Vorticist group of painters. Coburn’s ink drawing on the cover of the catalogue was closer to a design for a kimono by the painter Paul Signac than to anything by the Vorticist painters or by the Vorticist sculptors Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Jacob Epstein. The eighteeen or so Vortographs Coburn made can be divided into three principal groups. The first group consists of a two-dimensional set of lines with an image of Pound in silhouette. They are flat designs. The second group, in which multiple exposure was added to the mirror effects, shows an increased number of overlapped diagonal lines in the manner of Lewis’s Composition (1913), for instance. The third group is visually derived from the drawings by Jacob Epstein for his Rock-drill (1913-15). Pound’s knowledge of photography was extremely limited:

Art photography has been stuck for twenty years. During that time practically no new effects have been achieved. Art photography is stale and suburban.97

To say that photography had made no progress since 1897 was nonsense, but Pound wanted to negate the influence of Impressionism with Vorticism:

. . . pleasure is derivable not only from the stroking or pushing of the retina by light waves of various colour, BUT ALSO by the impact of those waves in certain arranged tracts.

But Coburn’s “Station Roofs, Pittsburgh” (1910) and pictures of New York from its pinnacles showed that he was perfectly capable of arranging his compositions in Vorticist tracts even if their origins were in Japanese composition rather than Italian Futurism. Key words like “impact” in Pound’s writing and his attacks on “blur” show that he was rejecting caressive and maternal Impressionism in favor of the clean thrust of Vorticism. He cultivated the idea of the hard edge. The sexual overtones of Vorticism, the protofascist cult of the male and of the warrior, are inescapable. The true mystery of life for Pound was coitus, and his hieratic head carved in stone by Gaudier was a monument to his cold phallicism. Pound wrote:

The modern will enjoy Vortograph No. 3, not because it reminds him of a shell bursting on a hillside, but because the arrangement of forms pleases him, as a phrase of Chopin must please him. He will enjoy Vortograph No. 8, not because it reminds him of a falling Zeppelin, but because he likes the arrangement of its blocks of dark and light.

Note that, despite his attack on representation, Pound was still forcibly reminded of concrete phenomena but rejected the shell in favor of Chopin, the zeppelin in favor of light and shade.

The proneness of the human mind to find meaning is, happily, inextinguishable. We will continue to like things because we recognize them, even as we enjoy our sensitivity to the forms that bring them into our minds. The joke is ultimately on Pound: we will never again look at “Vortograph No. 8” without thinking of a zeppelin. After more than half a century of blocks of dark and light we are not impressed by them alone. The saddest aspect of Coburn’s experiments is that they took place at the moment when the image produced by the Vortescope most resembled what he knew to be preexisting Vorticist imagery.

The Vortographs are wholly derivative and deflect us from Coburn’s great work as a photographer.

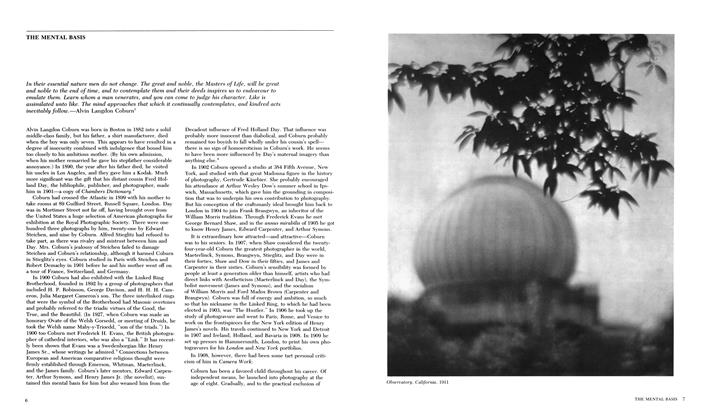

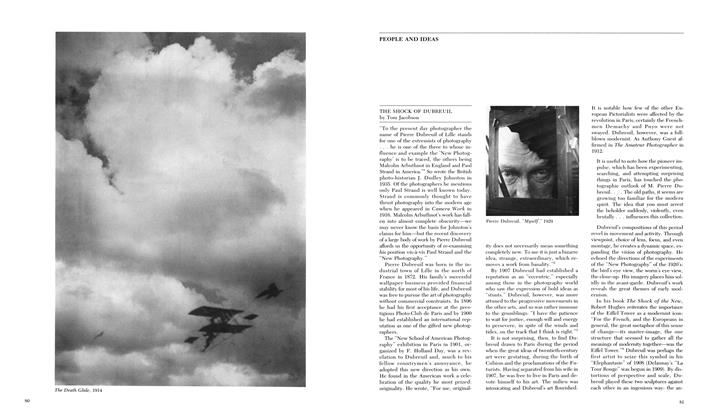

The idea of the bursting shell and the falling zeppelin should be compared with Coburn’s “The Death Glide” (See: Page 80). If the Vorticist emphasized the orgasmic nature of death, the Symbolist stressed a less dramatic transition from one spiritual state to another. Pound conceived of woman as an octopus98—a chaos requiring the weightless shadow of the phallus to bring her to law and light. Coburn’s octopus photograph was not based on such an attitude. He was a quietist in both sex and religion. The aggressive phallicism of the Vorticist was alien to his nature. When he introduced himself to George Meredith, the poet of Modern Love, he did so by sending him a photograph of a golden-haired young mother giving her infant the breast. His interest in Lewis Carroll’s photographic work, with its fixation on prepubescent girls, is an indication of his sexual immaturity. He was not an aggressively heterosexual figure like Pound, Stieglitz, or Steichen, but treated marriage and religion as a solution to his personal problems. The way Coburn wrote about his wife was extraordinary:

She did not have any children of her own, but she would have made a lovely mother, and much of her maternal feeling was lavished on this unworthy little boy, which I did my best to appreciate.

When Pound was broadcasting on behalf of Mussolini during World War II, Coburn was turning his home in North Wales into a hospital for the Red Cross. The men’s essential natures had achieved final expression.

Whether a certain romantic, sexual agony is necessary to the production of art is an old question. At about the same time that Coburn was finally giving up art for religion in 1924, the American poet in the Stieglitz circle, Hart Crane, author of The Bridge, was disputing this subject with Gorham Munson, an important man of American letters in the twenties. Munson understood that early life influences begun in vanity, pride, and ambition sometimes mature under the influence of art and religion and strike a level of consciousness that he called the influence of an occult school. What gripped young Americans in 1924 was the development of P. D. Ouspensky’s ideas by G. I. Gurdjieff, as disseminated by the English writer A. R. Orage, who was then in New York giving demonstrations and lectures on the Harmonious Development of Man. In Britain, Coburn was coming under the analogous influence of such a school. But unlike Crane, who came to resent and reject the influence, Coburn took to it utterly. Crane argued that the discipline of self-knowledge, the eradication of the self that plagued and vexed the soul, stopped people from writing. As Munson put it:

Discipline suggests a price to be paid. The passivity and inertia of one’s psychology resist discipline. There is a fear of losing the life one has. Man is strangely attached to his weaknesses. Sometimes he would like to grow out of them, but not at the price of hard struggle against them. In a crisis of life-change men find that they love their suffering and are fearful of the vista of a new life.100

Crane, who was homosexual, would not pay the price—drink and probable suicide followed as he tried to keep writing in the life image of the poet Rimbaud. Coburn was willing to pay the price—calm and contentment followed, but no photography to speak of. He had exchanged the Symbolist sensibility—immaturity, vexation, and all—for the concept of Awen (the name he gave his last house in North Wales). The Shrine of Wisdom described Awen as the Druidic principle of unity within the soul, the principle by which individual consciousness is united with God:

According to the Ancient Bards, the presence of Awen is to be realized “by habituating one’s self to the holy life, with all love towards God and man, all justice and mercy, all generosity, all endurance, and all peace, by practising the good disciplinary arts and sciences, by avoiding pride, cruelty, uncleanness, killing, stealing, covetousness, and all injustice; by avoiding all things that corrupt and quench the light of Awen where it exists and which prevent its participation where it is present.”101

Discipline of this kind resulted ultimately in a sterilizing puritanism that Coburn welcomed and Crane fiercely rejected. One of them lived to be eighty-four, the other died at thirty-three.

As “young Parsifal” and “the Hustler” Coburn had suffered. As a member of the Universal Order he found a way to still his desires and attain peace of mind. The Symbolist photographer became the Mason, the devotee of Japanese art became the Taoist, and the Bostonian comparative religionist found a home in the Church in Wales.

As a Symbolist photographer Coburn was influenced by spiritual values and a concept of hidden knowledge but kept up his endless search for meaning in nature. A degree of agony was grist for his mill. The assumption of being in possession of meaning and having attained enlightenment leads to the complacent idea that one is a complete or perfected person whose role is to teach others. The mystic may continue to be an artist, but the mystagogue must be a teacher. Hart Crane expressed a healthy resentment toward the mystagogue. Coburn undoubtedly became a teacher, though not, of course, of the monologic kind like Gurdjieff. The Universal Order was dialogic and was committed to avoiding all cults of personality.

When the history of modernism comes to be written from a religious rather than formalist point of view, it will be seen that abstract artists like Kandinsky, Mondrian, and Malevich proceeded from symbolic rather than abstract ideas. Far from being formal experiments, their work was based on spiritual and utopian ideas. Equally, it is possible to see Coburn’s work as the logical extension of his decided tendency toward the gradual elimination of the facts of nature in favor of its mysterious appearances, which early on had led to a concern, stimulated by Dow, with pattern, decoration, and design but, under the influence of Symons, never out of touch with reality. Coburn’s emphasis was, in the end, on a municipal rather than an abstract sublime. He did not, like Mondrian and Malevich, construct an abstract language in which to represent spiritual ideas but considered the visible, urban world a conjectural rather than absolute symbol of the invisible. He subscribed to a theory of expression rather than of abstraction. The Vortographs represent a momentary lapse in favor of abstraction, when evoked meaning gave way to pure form.

If an objet d art is a created artifact and an objet trouvé is an object found in the world, there ought to be a name for an object that is both made and found at the same moment—an object transfigured rather than manipulated, presented rather than represented, inscribed rather than described. To see a naturalistic object in a new light, under this transformed aspect, is the great gift within the power of a fine photographer. To make such a picture is to know enough. To know too much is to stop responding to nature in favor of merely contemplating it. By 1924 Coburn was indeed the man who knew too much. The animus of art had been finally subsumed under the mental impulse of religion, and his ethical development had assuaged his need to participate further in the competitive world of photography.