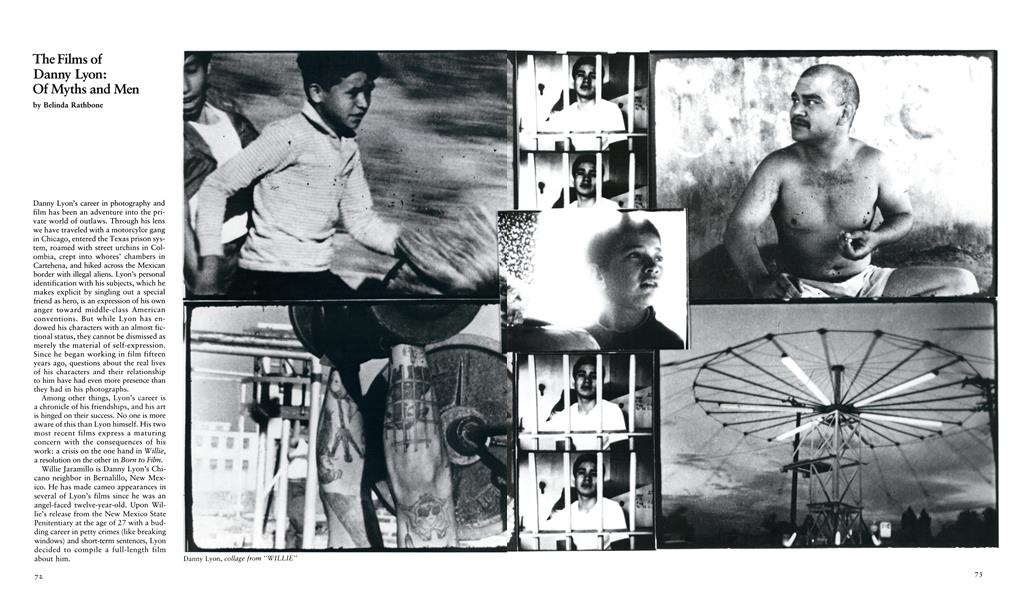

The Films of Danny Lyon: Of Myths and Men

Belinda Rathbone

Danny Lyon's career in photography and film has been an adventure into the private world of outlaws. Through his lens we have traveled with a motorcylce gang in Chicago, entered the Texas prison system, roamed with street urchins in Colombia, crept into whores' chambers in Cartehena, and hiked across the Mexican border with illegal aliens. Lyon’s personal identification with his subjects, which he makes explicit by singling out a special friend as hero, is an expression of his own anger toward middle-class American conventions. But while Lyon has endowed his characters with an almost fictional status, they cannot be dismissed as merely the material of self-expression. Since he began working in film fifteen years ago, questions about the real lives of his characters and their relationship to him have had even more presence than they had in his photographs.

Among other things, Lyon’s career is a chronicle of his friendships, and his art is hinged on their success. No one is more aware of this than Lyon himself. His two most recent films express a maturing concern with the consequences of his work: a crisis on the one hand in Willie, a resolution on the other in Born to Film.

Willie Jaramillo is Danny Lyon’s Chicano neighbor in Bernalillo, New Mexico. He has made cameo appearances in several of Lyon’s films since he was an angel-faced twelve-year-old. Upon Willie’s release from the New Mexico State Penitentiary at the age of 27 with a budding career in petty crimes (like breaking windows) and short-term sentences, Lyon decided to compile a full-length film about him.

From the beginning Willie strikes a note of hopelessness. No longer the young idealist yearning for the experience of older men, Lyon is now the disappointed mentor searching for the logic of Willie’s decline. “He’s a space case,” says Willie’s nephew, Jamie; and when the filmmaker asks him if Willie wants to get out of jail, Jamie answers, “No, he likes it there.” Willie’s brother, Fernando, blunts any further attempts at reasoning when he states philosophically, “That’s his life, and Fve got my life and you’ve got your life.”

The film is a helpless backward glance, a search for meaning in despair of finding it. Memories of childhood interrupt the present. Scenes of Willie as a little boy cut from Lyon’s own footage suggest the filmmaker’s hope for his subject and add to the rhythm of sorrow and repetition. There is no sense of progress, only falling, backward. Willie is tossed in and out of jail without any clear evidence as to why or when. The dreadful boredom of prison life is vivid as Lyon pans through Willie’s cell-block; each captive rises to the bait of the movie camera until finally we find Willie, our reluctant hero, hiding his head under a sun visor, overcome, it seems, by the pressure to perform. In another scene we find Willie at a prison hymn sing following the drone of the guitarist preacher on the other side of the bars while his fellow inmates watch TV, doze on the table, or hide behind their hymnals. Even in the images of Willie’s freedom outside the prison walls, there is the depressing hum of monotony. At home Willie dances alone, his hands stuffed in his pockets as he shuffles around the room to the melancholic beat of “Because” by the Dave Clark Five; in an amusement park a ferris wheel spins round and round in the summer twilight. “My mistake was coming back to this town,” says Willie. “If I had another place to go, I would. But I don’t have no place to go to.”

While Lyon’s earlier work is striking for the artist’s remarkable rapport with dangerous and alienated men, Willie contains many signs of rejection. Lyon cannot reach this lethargic youth as easily as he could reach, for example, the lonely middle-aged, life-sentenced Billy McCune, the hero of Conversations with the Dead. And while McCune sprouted a primitive artistic drive in an effort to stay human in inhuman conditions and carried on a lively correspondence with the author, Willie flounders between passive religious chanting and animal rage. What becomes, one must wonder, of Lyon’s romance with the underdog as he himself grows older and gradually shifts his role from admirer to sage?

Lyon’s turn from photography to film in 1969 coincides with the waning of his youthful idealism. With his first film, Social Sciences 127, a 21 minute sketch of a veteran tattoo artist by the name of Bill Sanders, we encounter for the first time the artist’s comic side and a cynicism aimed directly at himself. Lyon presents Sanders as a kind of photo-anthropologist. Sanders rambles on about his clients to the buzz of his electric needle as Lyon pans across the walls of his shop, which are covered with fading Polaroids of his proud customers displaying tattoos on their arms, breasts, thighs, or wherever. Lyon chose to use film in the case of Sanders “because he was the photographer.” This haphazard amateur collage spoke altogether a different language from the one that Lyon already spoke so fluently. Bill Sanders’s wall of Polaroids suggests the total lack of design he had over the entries and exits of his customers, a messy inconclusiveness. Lyon’s homage to the older, wiser, and more primitive Sanders—who “knew more about what a photograph is than most museum curators”—expresses a growing distrust of his own attempts to make social statements through elegant and wellordered imagery, a distrust of the romantic in himself.

Social Sciences 127 arrives directly on the heels of Conversations with the Dead, Lyon’s most refined and commercially successful book of photographs. At the moment when he achieved greatest control over his medium, when his images threatened to become classics (which they are), Lyon decided to move on, explaining his turn to film as a desire for a greater sense of realism.

In documentary film, more than in photography, the artist’s deal with chance is precarious. Using an inherently narrative medium to tell what is not exactly a story, the filmmaker struggles against the natural incoherence of events or gives in to their chaos. The tension between what is happening and what the filmmaker wants to happen, the very reason that so many documentary filmmakers eventually move on to fiction, is perhaps what Lyon was seeking—a more honest, if more apparently flawed, confrontation with his subjects.

Self-doubts about the duplicity of his medium have nagged at Lyon since he began his career more than twenty years ago. In his introduction to The Bikeriders, he expresses his fear of glamorizing his subjects, saying of his friend Cal that if he became the hero of a book, he might “perish on the coffee tables of America.” With this he echoes the young James Agee who, in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, devotes as much attention to his own agony as a journalist as he does to the tenant farmers he has been assigned to describe. Likewise, Lyon is poised between his loyalty to Cal as a real person and the business of making him a photoliterary figure. What is ironic about this kind of intimate journalism in which the journalist implicates himself as mediator is that in his effort to reveal the truth, he endows his subject with a nearly mythical status. And the more extreme the attention to detail and the more reverent the approach to the subject’s own artless expression, the more literary they become. In Conversations with the Dead, the FBI reports and personal correspondence that document the real lives of the prison inmates extend this tradition. “In the sense that any dream is a work of art, so is any letter,” Agee wrote. “The variety to be found in any letter is almost as unlimited as literate human experience; their monotony is equally valuable.”

Conversations with the Dead has been construed as a political statement by some, but it is only so in the sense that any worthwhile work of literature is subversive at its core. Lyon is too involved with his subject and too passionate to sort out matters better left to criminologists. He is more interested in describing the experience of being there and once again apologizes for the inadequacy of photographs: “the material I have collected here doesn’t approach for a moment the feeling you get standing for two minutes in the corridor of Ellis.” He concedes to the greater wisdom of the naive: I have found someone much more eloquent than I to explain to the free world what life in prison is like” (Billy McCune). By its very title, Lyon suggests that Conversations with the Dead is a book about something much larger and more timeless than the specifics of the Texas Department of Corrections.

Lyon’s films are more “real” than his photographs. His characters are less idealized, their gestures less refined and more humorous, their speech less eloquent than letters. Scenes in Willie of the prison yard and cell-block take us a step closer, perhaps, to the feeling Lyon couldn’t describe about the corridor of Ellis. The miracles of candid film imagery have moments of unexpected brilliance in this film, moments beyond the imagination of any screenwriter, moments so obscure it would be impossible to describe them here. And the sound of the swinging speed bag in the prison yard or the leaden chorus of prisoners obediently singing “we shall never be discouraged . . .” has a philosophical ring as powerful as anything that can be written.

Lyon’s familiarity with prisons and prison types is evident. The feeling of intimacy he achieves in this film makes prison life seem, in a way, less threatening than before; it also seems more ridiculous. Everyone appears to be young and of similar background. The kind of forced sense of humor and camaraderie that exist among peers who are thrown together against their wills make the whole scene something like a third-rate boarding school for drop-outs.

In the midst of extraordinary film opportunities, Lyon has to struggle to remain faithful to his nominal subject. His attention wanders, naturally, to Willie’s more engaging cell-block neighbors such as “The General,” who performs Kung Fu for the camera; Frank Martinez, a hyper-talkative marijuana farmer; Julian Romero, a fastidious inmate rearranging his belongings in his cell; and Michael Guzman, a coy young murderer on death row. While the film spontaneously brings us face to face with these characters, it also exposes Lyon’s isolation from his main character, and the very unnatural act of trailing someone with a movie camera and sound equipment. As with so many documentary films, this one works best when Lyon follows his intuition and not his sense of purpose.

But beyond the technical details of filmmaking, the most disturbing thing about Willie is Willie. Many of Danny Lyon’s characters have succeeded as heroes because he has enlarged one moment in their lives; they are single frames taken out of context and out of time. We discover them in the same spirit as Lyon did, with unreserved fascination. Cal the biker, Billy McCune the convict, and Eddie the wetback rest safely in the annals of photo-literature; meanwhile, backstage, the real drama of Lyon’s own life continues. “I got tired of being a Chicago Outlaw,” Lyon confessed not long ago. “After the pictures and the writing were done, I really couldn’t stand it anymore, having to drink three quarts of beer every Friday night.” Willie Jaramillo is the only character Lyon knew before he went astray, and the film was inspired by someone who is now lost in the past. Not only does Willie turn out to be a failure in the eyes of society (which would be alright with Lyon), he is a failure as a rebel, which is more serious. For a rebel to be a hero he must be courageous, at least superficially, and Willie is a coward. In retrospect many of Lyon’s heroes are not all that courageous, but they seemed to be because Lyon believed them to be. The difference with Willie is that the filmmaker’s disappointment in his hero is as much a presence in the film as Willie’s reluctance to be one.

The freedom that has allowed Lyon to make friends with wayward men is the same freedom that, perhaps, requires him to leave most of them behind. If Lyon’s earlier work is about the artist’s own escape from his middle-class background, Willie is about imprisonment more profound than the walls of a cell. It is an admission of defeat at trying to make a friend of an alien or a hero out of a nobody. Whether or not Willie fails as a film, it is a film about failure. The onward progress of Lyon’s life and his art have given him a vision that is unbecoming to rebels.

Fortunately, Lyon’s sense of hope for humanity has other outlets. Born to Film is both a posthumous tribute to his father, who was an amateur filmmaker, and a training film for Lyon’s son. The film is a compilation of Ernst Lyon’s home movies showing the filmmaker as a little boy, and his own footage of his son Raphe enduring similar growing pains. A dialogue between Danny Lyon and his son runs throughout as they look at old family films: “Who’s that army guy?” (Raphe); “That’s my father, that’s Ernst” (Danny).

While he teaches Raphe to respect the work of forgotten men, as well as to overcome his fear of the strange and new, the themes of Danny Lyon’s career converge. Memories are around one corner, danger around the other. A friendly snake curls around Raphe’s neck at the editing table, causing some concern; meanwhile the filmmaker as a little boy watches in horror as a family friend decapitates a chicken on a farm. In another scene the pet snake (returned to her glass box) strangles and devours a mouse, while outside, on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, a hooker makes her daily march and a drug addict is carried away on a stretcher. The film closes with a scene of Raphe blindfolded, learning from a blind man what it’s like not to see, a complement to the opening scene of a rodeo rider hanging upside down from a galloping horse. And finally, to the lonely and terrible sound of sirens, Ernst Lyon writes “The End” in the sand with a stick as it is erased by the tide.

Bom to Film is as seductive as a system of mirrors—mirrors, in fact, being one of its motifs, a metaphor for looking backward. This homemade collage recalls Bill Sanders tattoo shop where the act and its historical proof exist in the same small room, where the artist works surrounded by memories of his personal encounters. The language of the camera is returned to its most revelatory and private function: the ability to hoard the past and even rearrange it. But then, this language is also subject to chance. As his son learns to distinguish between myth and reality, Danny Lyon himself is still in pursuit of that rare moment when they are one and the same.

WILLIE and BORN TO FILM are avadable for $49.00 each on VHS video casssette from Bleak Beauty, Box 295, New Suffolk, NY 11956. Tel: 516-734-6774.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

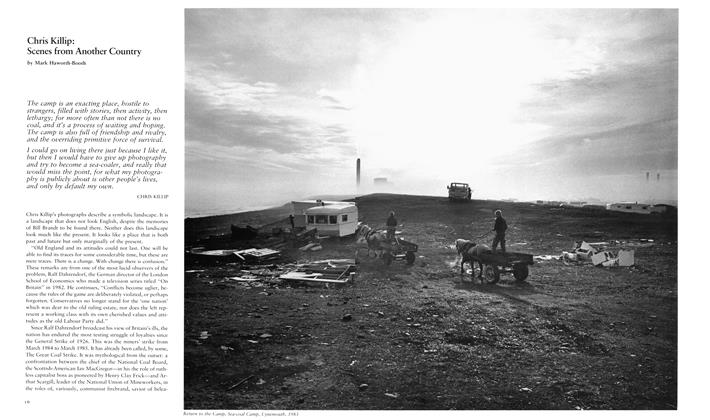

Chris Killip: Scenes From Another Country

Summer 1986 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

Nan Goldin's Ballad Of Sexual Dependency

Summer 1986 By Mark Holborn -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasAn Argument With History

Summer 1986 By Ron Horning -

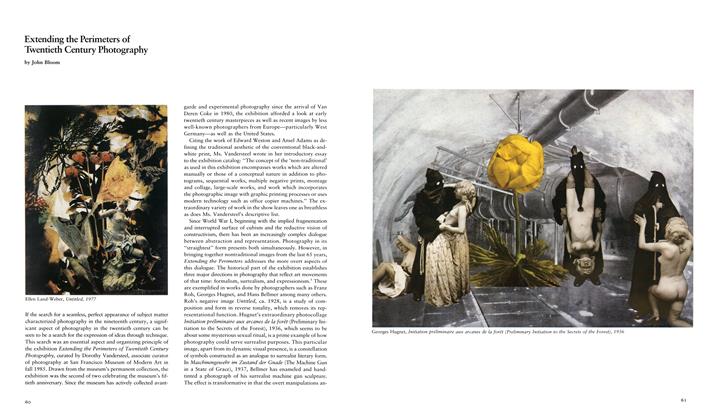

Extending The Perimeters Of Twentieth Century Photography

Summer 1986 By John Bloom -

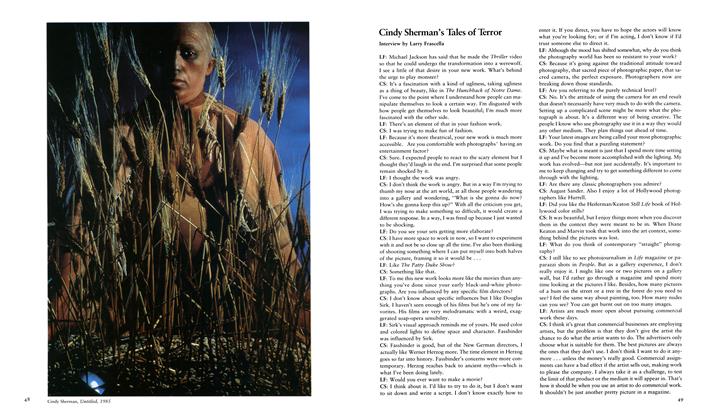

Cindy Sherman's Tales Of Terror

Summer 1986 By Larry Frascella -

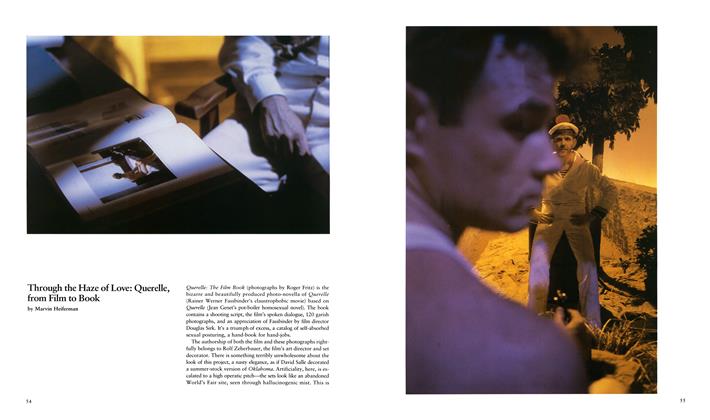

Through The Haze Of Love: Querelle, From Film To Book

Summer 1986 By Marvin Heiferman