To be a child is not an affair of bow old one is. “Child” like “angel” is a concept, a realm of possible being. Many children have never been allowed to stray into childhood. Sometimes I dream at last of becoming a child.

A child can be an artist, he can be a poet. But can a child be a banker? It is in such an affair as running a bank or managing a store or directing a war that adulthood counts, an experienced mind. It is in the world of these pursuits that “experience” counts. One, two, three, times divided by. The secret of genius lies in this: that here experience is not made to count. Where experience knows nothing of counting, it creates only itself out of itself.

ROBERT DUNCAN, On Children, Art and Love

Dream Portraits

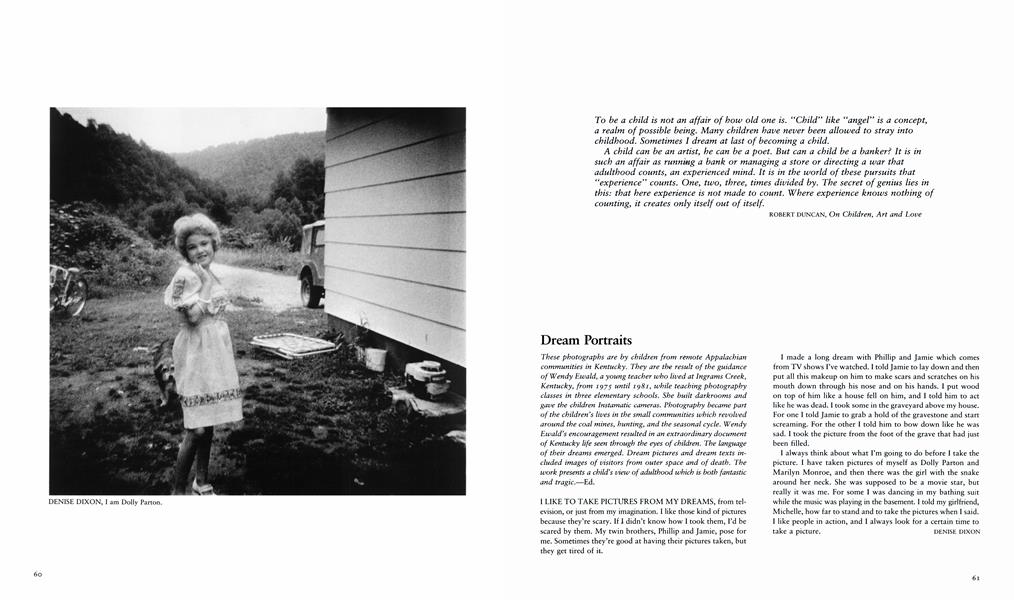

These photographs are by children from remote Appalachian communities in Kentucky. They are the result of the guidance of Wendy Ewald, a young teacher who lived at Ingrams Creek, Kentucky, from 1975 until 1981, while teaching photography classes in three elementary schools. She built darkrooms and gave the children Instamatic cameras. Photography became part of the children s lives in the small communities which revolved around the coal mines, hunting, and the seasonal cycle. Wendy Ewald’'s encouragement resulted in an extraordinary document of Kentucky life seen through the eyes of children. The language of their dreams emerged. Dream pictures and dream texts included images of visitors from outer space and of death. The work presents a child’s view of adulthood which is both fantastic and tragic.—Ed.

I LIKE TO TAKE PICTURES FROM MY DREAMS, from television, or just from my imagination. I like those kind of pictures because they’re scary. If 1 didn’t know how I took them, I’d be scared by them. My twin brothers, Phillip and Jamie, pose for me. Sometimes they’re good at having their pictures taken, but they get tired of it.

I made a long dream with Phillip and Jamie which comes from TV shows I’ve watched. I told Jamie to lay down and then put all this makeup on him to make scars and scratches on his mouth down through his nose and on his hands. I put wood on top of him like a house fell on him, and I told him to act like he was dead. I took some in the graveyard above my house. For one I told Jamie to grab a hold of the gravestone and start screaming. For the other I told him to bow down like he was sad. I took the picture from the foot of the grave that had just been filled.

I always think about what I’m going to do before I take the picture. I have taken pictures of myself as Dolly Parton and Marilyn Monroe, and then there was the girl with the snake around her neck. She was supposed to be a movie star, but really it was me. For some I was dancing in my bathing suit while the music was playing in the basement. I told my girlfriend, Michelle, how far to stand and to take the pictures when I said. I like people in action, and I always look for a certain time to take a picture.

DENISE DIXON

To dream some of the dreams Tve dreamed my mind has to be five or six times as big as the world. There are different places in my mind. Just all over space, earth, everywhere something needs to be straightened out. And it’s just full of a bunch of machines making it go. DARLENE WATTS

Representation is not a singular act but a continuous and repetitive process of symbolization, a dense and hierarchical vocabulary of the world once removed. “Reality” is increasingly the vanishing point of its image, the inaccessible “other” and “elsewhere” of a copious landscape of articulated separation. . .

. . . The entry into an image, the rupture and reintegration of its coherent form, exposes that which lies between meaning, the reciprocal meeting of an object and its apprehension.

SARAH CHARLESWORTH

We like to imagine the future as a place where people loved abstraction before they encountered sentimentality.

SHERRIE LEVINE

The mystery of time, the magic of light, the enigma of reality—and their interrelationships—are my constant themes and preoccupations. Because of these metaphysical and poetic preoccupations, I frequently attempt to show in my work, in various ways, the unreality of the “real” and the reality of the “unreal.” This may result, at times, in some disturbing effects. But art should be disturbing; it should make us both think and feel; it should infect the subconscious as well as the conscious mind; it should never allow complacency nor condone the status quo.

My central position, therefore, is one of extreme romanticism—the concept of “reality” as being, innately, mystery and magic; the intuitive awareness of the power of the “unknown”—which human beings are afraid to realize, and which none of their religious and intellectual systems can really take into account. This romanticism revolves upon the feeling that the world is far stranger than we think; that the “reality” we think we know is only a small part of a “total reality;” and that the human imagination is the key to this hidden, and more inclusive, “reality.”

CLARENCE JOHN LAUGHLIN, The Personal Eye

Poe, in Ligeia, quotes Bacon: “There is no exquisite beauty without some strangeness in the proportion.” This, at last, is the final rallying cry of the Romantics. Mae West, oracular to the end, would dare to say it a little too amusingly to suit Clarence, when she says to her dwarf: “Honey, you ain’t seen nuthin’ yet!” Where the Lady stops, nobody knows. Give Clarence John Laughlin an object—the chances are exactly the same. It’s a brandnew ball game, fans, and we’re going into extra innings . . .

JONATHAN WILLIAMS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

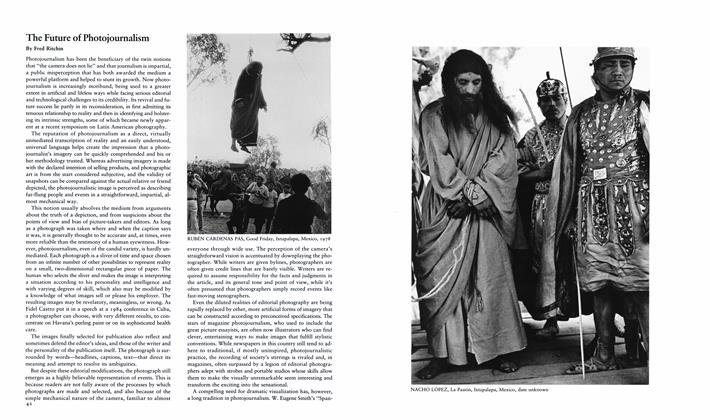

The Future Of Photojournalism

Fall 1985 By Fred Ritchin -

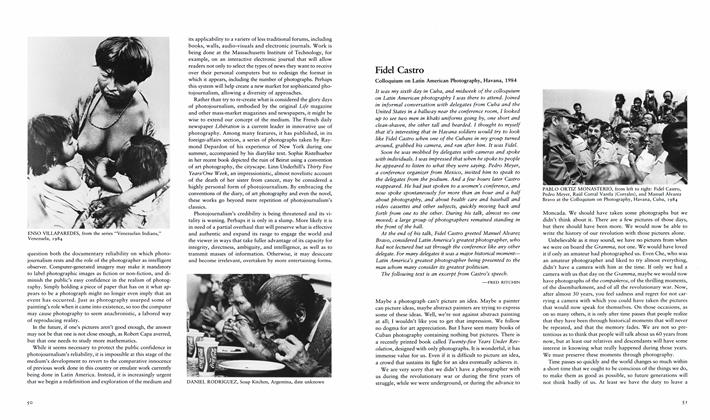

Fidel Castro: Colloquium On Latin American Photography, Havana, 1984

Fall 1985 By Fred Ritchin, Sarah Charlesworth -

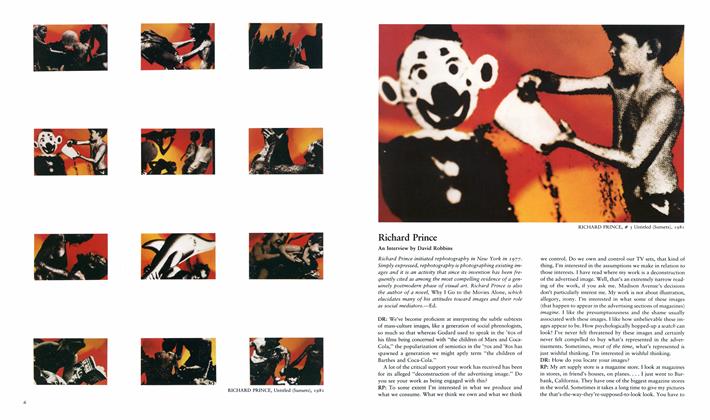

Richard Prince: An Interview By David Robbins

Fall 1985 By David Robbins -

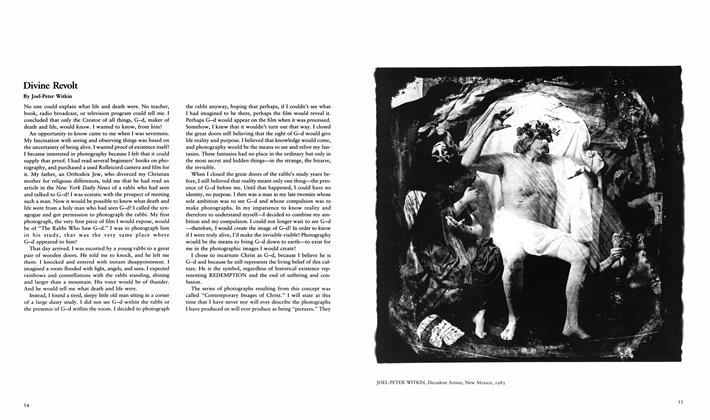

Divine Revolt

Fall 1985 By Joel-Peter Witkin -

Black Dice

Fall 1985 By John Baldessari -

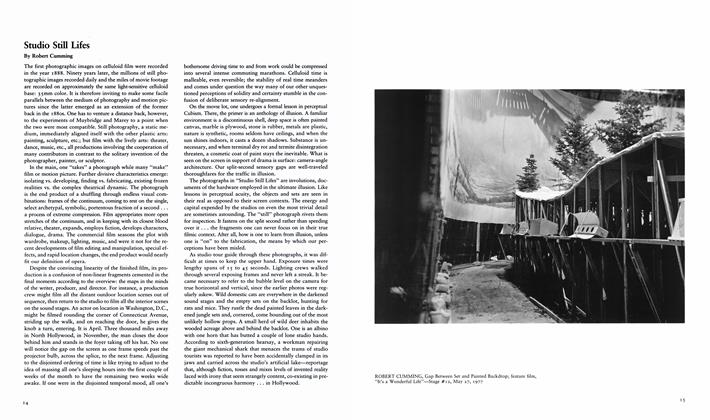

Studio Still Lifes

Fall 1985 By Robert Cumming