Towards a Proper Silence

NINETEENTH-CENTURY PHOTOGRAPHS OF THE AMERICAN LANDSCAPE

Robert Adams

We try hard not to be sentimental, not to feel more emotion for a subject than it deserves. Old landscape photographs are, however, sometimes cited as temptations. If the open America we loved is gone, then its recollection and the grief that inspires may be useless.

The force of this argument comes from our shock at the state of the current West. When else has a region of more than a million square miles been so damaged in so short a time? We catch ourselves thinking, in the bitterness that can accompany the unexpected sound of an aluminum can bending underfoot, that it would have been merciful if Columbus had been wrong and the world flat, with an edge from which to fall, rather than a circular cage that returns us to our mistakes. The geography seems hopeless.

It is true, admittedly, that the West has historically been filled in a series of sudden invasions, and that our present experience is in certain respects no different. The invasion that followed in the two decades after the Civil War—a time when many extraordinary photographs of the landscape were made—was itself facilitated as ours has been by new technology (theirs included such things as the invention of barbed wire and the completion of the transcontinental railroad). It was a period as well, like ours, of brutality; John Muir observed, as did others, that “nearly all railroads are bordered by belts of desolation,” perhaps referring to events like the killing of more than a million buffalo for their tongues alone. Even the junk the early intruders scattered forecast ours; a new arrival to Denver in 1869 wrote that “the prairie is littered for miles with old tin cans and empty bottles.”

What sets our recent experience apart, though, is first of all the scale of what has happened. It would not have been especially hard in the early part of this century to have retraced exactly the early photographers’ travels, but by the 1960s and ’70s one would have had to have been a confirmed trespasser; thousands of miles of roads were abruptly walled off by private property signs (meaning, often, corporate property), and even if one made it through to the photographers’ vantage points one was likely to discover that their subjects were flat gone— the Salt Lake Valley under smog, many of the canyons under water, Shoshone Falls reduced to support irrigation, Mono Lake drained down the aqueduct to Los Angeles. Suddenly the size of the American space proved no defense.

The first useful thing of which nineteenth-century photographs remind us is, I think, that space is not simple. We have tended to think it remained until we marked it off with fences or roads, or until we put buildings in it; if we could see to the horizon free of these things we assumed space remained. But as a short walk in the Southwest now often proves, it may be possible to see little but rabbitbrush for miles and yet know that the area is overpopulated.

Among the most compelling truths in some of the early photographs is their implication of silence. Western space was mostly quiet, a fact suggested metaphorically by the pictures’ visual stillness (a matter both of their subject and composition). What sound there was in front of the camera a hundred years ago usually came from the wind, though even that stirred few trees; running water appears in some of the pictures, but it was an exception; relative to the East there were not even many birds.

Now the noise level is far greater. The degree of change is demonstrated nearly everywhere, but I remember learning its complexity once as I photographed a remote church on the Colorado high plains; throughout the afternoon I studied the outside of the building from locations in the open fields to all sides, and alternately looked at the expanse from inside the church, through its simple lancet windows (one of the mysteries of space being that it sometimes seems bigger through a frame). At dusk I watched a line of clouds on the eastern horizon, white and rose, and then lightning far away in Nebraska, silent. In the morning, however, the place disappeared in sound. At first it had all seemed to be whole with the previous day: a coyote barked, the sun rose through a mist, and wildflowers opened. As I worked to set up a camera, though, there began and built to full volume in three or four seconds a noise of indescribable intensity; I turned to see a fighter plane, no more than two hundred feet off the ground and to the side of me, emerge from the haze and then disappear back into it, the heavy, terrible rush of its engine fading for many seconds out across the prairie. Eventually all was as quiet as it had been before, but the identity of the place, an identity dependent on the unbroken silence of space, was lost to me.

Another quality of space of which I am reminded when I look at old photographs is the easy tempo of life within it— often space looks nearly unmoving—and by extension the tempo appropriate for anyone who hopes to experience space. The pinsharp views (how long did the photographer have to wait out the wind?) were made only after establishing what amounted to a little camp in order to prepare the plates, and then taken only by substantial time exposure. They suggest, through the photographer’s patience, an appropriately respectful acknowledgment of the geologic and botanic time it took to shape the space itself. How can we hope, after all, to see a tree or rock or clear north sky if we do not adopt a little of its mode of life, a little of its time.

To put this another way, if we consider the difference between William Henry Jackson packing in his cameras by mule, and the person stepping for a moment from his car to take a picture with an Instamatic, it becomes clear how some of our space has vanished; if the time it takes to cross space is a way by which we define it, then to arrive at a view of space “in no time” is to have denied its reality (there are in fact few good snapshots of space). Edward Hoagland once observed that Walt Whitman would have enjoyed driving, which is surely true in the sense that he loved to see all he could so that he could assemble those long catalogues of his; after a few days at the wheel, though, I suspect Whitman’s love of space might have brought him back to walking, since only at that speed is America the size he believed it. The poet William Stafford has written about the relation of time and walking to the settlement of open America, about

Pioneers, for whom history was walking through dead grass and the main things that happened were miles and the time of day.1

Space does, it is true, occasionally have other speeds, as of antelope, which can run as fast as a car, though only for a brief while, but the common pace is more like that of tumbleweed, comic plants that wallop along at a rate we can usually match on foot (farmers on the plains have regrettably now found ways to strip wild growth from fence rows, denying us the plant’s reminder of the velocity by which space is preserved). Little wonder that we, car-addicted, find the old pictures of openness—pictures usually without any blur, and made by what seems a ritual of patience—wonderful. They restore to us knowledge of a place we seek but lose in the rush of our search. Though to enjoy even the pictures, much less the space itself, requires that we be still longer than is our custom.

Another subtlety of space of which the photographs constructively remind us is the shaping, animating part played there by light. The intensity of sunlight in the West sets the region apart (Nabokov observed that only in Colorado had he seen skies—so clear that if one looks straight up they appear blueblack—like those of central Russia). The early photographers were limited in what they could show of variations in the sky, but they effectively suggested the power of light by juxtaposing bright, bleached ground against areas of deep shadow.

One remembers those pictures now, with their impression of arcing light, when one visits places like the bluffs above Green River, Wyoming, and sees there the numerous sources of aerial contamination that on some days make it look like the Ruhr, the sky dulled. Physically, much of the land is almost as empty as it was when Jackson and Timothy O’Sullivan photographed there, but the beauty of the space—the sense that everything in it is alive and valuable—is gone. Exactly how this happens I do not think can be explained, any more than can the opening verses of Genesis about light’s part in giving form to the void. But the importance of pure light is a fact for any photographer to experience; with it pictures of space are easy, and without it they are a struggle; though the difference between a clean sky and a smoggy one is not felt only by photographers. How emphatically absolute the distinction can be—we might at first suppose air pollution to be insubstantial and relative—was synopsized for me by the reaction of a woman who arrived in Denver in the 1960s to consider it as a home for her family; almost at once she phoned her husband who was working in Connecticut—he had been stationed in Denver during the Second World War—and said simply, referring to the landscape he had seen, “It’s not here anymore.”

Each of these aspects of space—its silence, its resistance to speed, and its revelation by light—seems to me usefully emphasized by nineteenth-century photographs because even today there are fragments of the American space to be protected, and that is something that is more likely to happen if we are clear about the nature of what is threatened. The difficulty is, however, that we do not seem much to love what space there is left. One thinks not only of the greed of developers, which is numbingly obvious, but of a widespread nihilism that now extends through much of the population, witness the reflexive littering, the use of spray paint on rocks, the girdling of trees near campgrounds, and the use of off-road vehicles for the maximum violence of their impact. The West has ended, it would seem, as the nation’s vacant lot, a place we valued at first for the wildflowers, and because the kids could play there, but where eventually we stole over and dumped the hedge clippings, and then the crankcase oil and dog manure, until finally now it has become such an eyesore that we hope someone will just buy it and build and get the thing over with. We are tired, I think, of staring at our corruption.

The sadness of this is, as the foregoing consideration of some of the qualities of space suggests, that areas of the American West are not wholly irredeemable. Though cities will not be unbuilt (some may disappear for lack of water), at least certain aspects of space, as suggested by the early pictures, could be partially restored—the land’s quiet, its impression of size and stability when encountered slowly, and its sun-irradiated beauty. Some places could, in short, be emptied. We could control sound pollution by regulating the design of tires, by outlawing dirt bikes, and by restricting routes open to airplanes; we could reduce the speed at which we travel through open country, not only by enforcing lower speeds on highways and waterways but by excluding motor vehicles entirely from whole areas; we could certainly better regulate light-impairing air pollution. Half damaged though the land is, we could keep what remaining space we have from shrinking, and perhaps even learn how, as the Japanese do with gardens, to make what there is seem, by our understanding care of it, bigger than it literally is, more spacious. At least there is no reason for a state like Kansas, with its ever-present horizon line, to seem small. Theodore Roethke described the peace that we might achieve:

The fields stretch out in long unbroken rows. We walk aware of what is far and close. Here distance is familiar as a friend. The feud we kept with space comes to an end.2

The possibility of such a reconciliation, based on the fact that some of the American space is recoverable, is part of what keeps the pictures from being of only sentimental interest. To love the old views is not entirely hopeless nostalgia, but rather an understandable and fitting passion for what can in some measure be ours again.

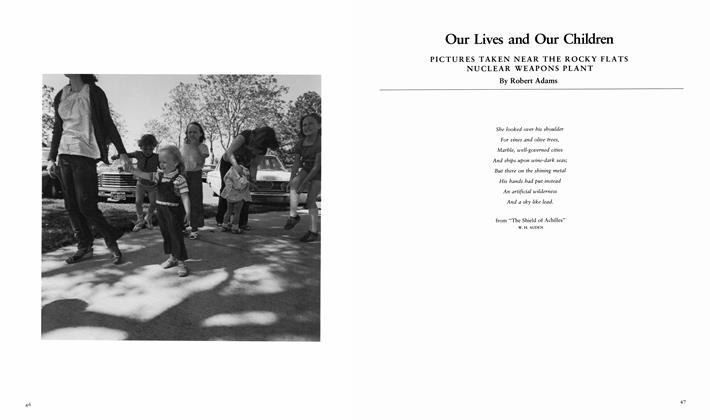

The condition of the western space now does raise questions, nonetheless, about our own nature. When I think, for example, of Denver, I wonder if we can save ourselves. On grassland northeast of the city, the Rocky Mountain Arsenal has buried in shallow trenches, without record of location, wheat rust agent made originally for germ warfare; the dump stands upwind of the American wheat bowl, and there is apparently nothing to prevent prairie dogs or a badger from someday opening it. To the west of the city, meanwhile, tableland has been so contaminated by fugitive plutonium from the Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant that developers have been forbidden to build there, the space having been poisoned for many generations to come. If we can do these things—and they are not by any means isolated evils—are we capable of decent behavior? (It is a doubt that qualifies our enthusiasm even for the achievements of NASA.) Is what has happened to the West a matter for those social scientists who take a mechanistic view of man, or for theologians, who see us as moral beings capable of choice?

The best answer to this unanswerable conundrum seems to me to be the compromise offered by classical tragedy. The plays are convincing I think because they falsify neither side of our ambiguous experience, which is of both freedom and fate— freedom as we know the world to be more exciting than the monotonies of a naturalistic novel, and fate as we live in a world worse than anyone could have desired.

In the plays of Sophocles and Shakespeare the hero is shown to believe, in ignorant pride, that he is godlike, which is to say free, and to learn through suffering that his freedom is paradoxical—to accept limits. Although presumably the photographers who took the early landscapes did not intend such an analysis of our country, since they witnessed no more than the opening events, their pictures do lead us now to reflect on a tragic progression. They remind us of the opportunity the openness provided for the confusion of space and freedom, an understandable but arrogant mistake for which we now suffer.

Space as we see it in the early pictures was not just a matter of long views, but also of distance from people. Many of the scenes are completely unpopulated, lacking any signs of man at all. Where there are figures they seem mostly to have been drafted from the photographer’s party. And when there are buildings or railroads they often appear to have gotten the photographer’s attention precisely because their presence was unusual.

In front of such landscapes it is easy to sympathize with those who lived out the early acts of our national misunderstanding of space. Little wonder that Americans said so confidently and unqualifiedly that they were free. How could they be otherwise—they were alone, or so it seemed. And they had gotten there as a result of their own effort. One of the striking things about many pioneer journals is that though the events described sound inexorable (disease, accident, failed crops), the feeling expressed is of having chosen the life. Even in accounts of river travel, where the course was set, there was a sense of liberty; Huck Finn, Twain’s incognito, expressed it almost every time he shoved the raft away from the bank, and Major Powell, no matter how deep in the confines of some gorge, wrote as if he were carried along mainly by the engine of his own enthusiastic choice.

At its best this equation of freedom with isolation from others has been understood as liberty to know oneself. In the words of Rosalie Sorrels, the contemporary composer and singer, the West “is the territory of space ... a place where people have gone so that they could hear the sounds of their own singing . . . so that they could hear their name if they were called . . . so that they could know what they think.” It is impossible even now, even after our tragedy, not to admire the spirit of that. One wonders, for example, if Abraham Lincoln’s character would have been the same had his family not been the sort to keep moving west as soon as they saw the arrival of neighbors.

A consideration of space and freedom and the American West begins logically, in fact, with the Civil War, a war about freedom (it also marks, conveniently, the starting point in America for serious, extensive landscape photography). A significant amount of the War was fought along the edge of the American space, and some even in it, as at Glorieta Pass, New Mexico. And the War’s conclusion made possible the beginning of the great invasion of western space. Indeed, as has often been pointed out, had those who enacted the war not been allowed to migrate in numbers into the West it is hard to see how the hatreds would have cooled as they did.

George N. Barnard’s pictures of holes blasted in the woods stand as frightening metaphors for what would follow the war; the bare ground and broken trees synopsize what was to be our violent assertion of our own space in space. As do all wars, the Civil War produced a generation of people tired of trying, of paying for ideals, and the condition of the West is to be explained in part by that generation’s cynicism and the pattern it set. Many immigrants saw their separation from others as a welcome freedom from responsibility. Liberty meant leaving people, whatever their needs, behind. We became a nation of boomers, everlastingly after a new start out in the open, by ourselves.

This morally indefensible equation of space, understood as distance from others, and freedom, understood as license to pursue one’s own interests without regard for those of others (no one else being in view), has ended of course in the reduction of everyone’s freedom. As the apparently infinite number of opportunities to start again stretched away westward, the mythology of capitalism appeared plausible. Anyone could, if the compulsion of his greed were left alone by government, go into the space, which was luckily well stocked with natural resources, and by work become rich. Mounting evidence to the contrary has for the most part been censored out in public education and the press, both influenced by profiteers, until now things have gone so far that the space has nearly been denied us. Ironically, corporate capitalism has for a century been allowed such sway that it has now, in the name of economic efficiency, almost cleared the space of exactly the people who wanted to enjoy it—small farmers, miners, and ranchers. We are left an urban nation, one today largely prohibited even visiting rights to the country. We look back at early pictures and marvel that the sheer size and beauty of the space could have absorbed and hidden for so long the damage done by unrestrained self-interest. Our destiny is to suffer the imprisonment of places like Los Angeles, with its twelve lane “freeways,” though whether in this we have the courage to find self-knowledge remains unclear.

What is the relevance of old photographs, then, to a country that has enacted a tragedy, that has, in Theodore Roethke’s words, “failed to live up to its geography”? Part of the answer is that the pictures tell us more accurately than any other documents we have exactly what we have destroyed. With the pictures in hand there is no escaping the gravity of our violence; the record is precise, as exact as the ruler O’Sullivan photographed against Inscription Rock in New Mexico.

What we are forced to see is that the West really was, despite all the temptations there are to romanticize the past, extraordinary—as extraordinary as the great flow of the Columbia River, the rock spires in Canyon de Chelly, or the deep space above the Sierra. The pictures make clear that before we came to it in numbers the West was perfect. The camera, as used by O’Sullivan and Jackson and Carleton E. Watkins and John K. Hillers, refutes every easy notion of progress, every sloppy assertion that we have improved things (early land promoters on the prairie actually argued that settlement would increase the rainfall!). When we look at what was there before us we are compelled to admit with the poet Cid Corman, “How obvious it is I couldn’t have imagined this.”

One way to judge the importance of the photographs is to compare them to paintings from the same time. Enough landmarks remain in something like their original form to check both photographers and painters against identical subjects, and with few exceptions the photographers come off better. I think for example of the painting now in the White House by Thomas Moran of the bluffs at Green River, a picture in which the sky seems derived from the English moors, lush and moist. It is a fiction, as are most of Moran’s finished paintings, just as are those by Albert Bierstadt, the other celebrity painter of the time.3

There are in fact only a few accurate nineteenth-century western landscape painters—Karl Bodmer, John Henry Hill, Worthington Whittridge, and Sanford Robinson Gifford are the only ones I would care to defend—and for the most part they made their reputations elsewhere, their contact with the West having been brief and geographically narrow.4 By contrast, photographic careers of lasting importance were built almost entirely in the West, and evidence a longer and wider acquaintance with the landscape.

Why painting, which earlier had flourished as a record of space along the eastern seaboard, succeeded so little in the West is a matter of speculation. The photographers may in some cases have been helped by the fact that their job was usually first to make a clear record for the War Department or the Geological Survey or the railroads; it was the sort of assignment to keep one moving and save one from pretense. But some of the painters were given similar priorities.

One suspects that the freshness of the photographic enterprise may have helped—the fact that there was a new way to see. Something at any rate appears to have built an enthusiasm that in turn contributed to endurance, and since the longer one is in a landscape, especially a spare one, the more one is likely to love it, it gave them an advantage, art being in the last analysis an affirmation, a statement of affection. Jackson, for instance, when he lost his job with the Geological Survey, never seriously considered leaving the West: “Whatever I might find for myself,” he wrote, “it must be in some great open country.” Few painters were that committed to the place. The photographers were the ones who were in it for keeps, and who were intoxicated by some of the spirit of that ad for film (recorded by Steve Fitch) on the road to Grand Canyon—“Hit the Rim Loaded.” It was fun. O’Sullivan is quoted, for example, as saying even of the desolate and mosquito-infested Humboldt Sink that “viewing there was as pleasant work as could be desired.” One supposes that the spell-binding nature of photography led them on just as it does us—the fact that in one take you can get it all right down to the individual leaves on the sagebrush.

The chief reason the photographers did better than the painters, however, was that when the painters were confronted with space they filled it with the products of their imaginations, whereas photographers were relatively unable to do that. The limits of the machine saved them. If there was “nothing” there, they had in some way to settle for that, and find a method to convince us to do the same. Generally speaking the painters imposed Switzerland on the Rockies, for instance, producing western landscapes that were crowded rather than spacious; they turned mountains vertiginous, hung thick atmospheric effects on peaks and through valleys, and placed in the foregrounds camps and grazing animals. Though photographers could and did steepen the apparent grade of mountains, they could only imperfectly register clouds (some like Barnard tried to print in skies from second negatives that had been exposed specifically to record them, but the composite usually betrayed itself at the horizon), and they hadn’t any chance at all, with their slow apparatus, of stopping camp activity or wildlife.

Nineteenth-century photographers of the West could not, in short, often bring landscapes to intense dramatic focus, as could painters, because they could not add to them. If the middle was empty, that was the way it had to be shown. (They could, of course, fill pictures with eccentricities like Shoshone Falls and El Capitan, but the meaning of these spectacles was ultimately to be found in the norm they exceeded, so that to concentrate on them exclusively would have produced a record as pointless as those tourist slide shows that unrelentingly take us to every spring and geyser in Yellowstone.) At their best the photographers accepted limitations and faced space as the antitheatrical puzzle it is—a stage without a center. The resulting pictures have an element almost of banality about them, but it is exactly this acknowledgment of the plain surface to things that helps legitimize the photographer’s difficult claim that the landscape is coherent. We know, as we recognize the commonness of places, that this is our world and that the photographer has not cheated on his way to his affirmation of meaning.

Among the reasons for enjoying the experience of space is the proof it offers of our small size. We feel in its presence the same relief expressed by the man who in 1902 managed to drive his car—the first one ever—to the edge of the Grand Canyon: “I stood there upon the rim of that tremendous chasm and forgot who I was and what I came there for.” It had apparently been one of those journeys away from oneself, in search of awe—a drive we still make.

Insofar as the western photographers were artists, however, their work helps us beyond a humbling realization of our small size to a conviction of our significance as part of the whole. We and everything else are shown, in the best pictures, to matter. The photographer’s experience was, it seems to me apparent from the pictures, finally not just of the scale but of the shape of space, and their achievement was to convey this graphically.

What they found was that by adjusting with fanatical, reverential care the camera’s angle of view and distance from the subject they could compose pictures so that the apparently vacant center was revealed as part of a cohesive totality. They showed space as itself an element in an overall structure, a landscape in which everything—mud, rocks, brush, and sky— was relevant to the picture, everything part of an exactly balanced form.

Art never, of course, explains or proves meaning—the picture is only a record of the artist’s witness to it. He or she can, however, be a convincing witness. In the case of these pictures we are helped to belief, I think, by the photographic approach— the views are mostly long shots that have been made with normal lenses (lenses that approximate the breadth and magnification of average human vision). It was a method that restricted the photographer’s opportunities to control our view of the subject (his only ways substantially to alter the composition being to hike farther, or to wait or return for different light), but the sense of objectivity it conveys tends to neutralize our skepticism. It is obviously easy to assert that life is coherent, but to work out the visual metaphor for that affirmation from within the limits of an almost ant-like perspective is hard and remarkable. One is reminded of George Steiner’s definition of classicism as “art by privation.” What kind of art could be more convincing in the depiction of the Southwest, of the desert, of a landscape that is by common standards deprived?

To go beyond showing mere size to a demonstration of form is important because awe by itself, without an accompanying conviction of pattern, can easily give way just to fear. Job was at last reconciled to life not by being shown only that he was small and therefore necessarily ignorant, but by being reminded of mysteries that are part of a creation in which all elements are subordinate to a design. The world, God tells Job, is a “vast expanse” but regulated by seasons, the heavens are immense but divided and given shape by stars like those in the Pleiades, and the oceans are an “unfathomable deep” but the appointed home for whales. By contrast it is an attention to size alone, at the expense of pattern, that makes so much romantic art so discomforting. One wishes romantics were compelled more often to live on the ocean or the prairie, where they could discover to what lengths the size of space might drive them. Ahab was fiction’s hyperbole, of course, actually doing battle with the inarticulate expanse, but his compulsion is there for any of us still to suffer, even if more passively. I think, for example, of a man on the Colorado prairie of whom I know, an exsubmariner who has relegated his orthodox house to storage and moved below ground into a roofed-over foundation, safely submerged.

To the extent that life is a process in which everything seems to be taken away, minimal landscapes are inevitably more, I think, than playgrounds for aesthetes. They are one of the extreme places where we live out with greater than usual awareness our search for an exception, for what is not taken away. How else explain, finally, the power of the best nineteenthcentury landscapes of space except as they result from this struggle.

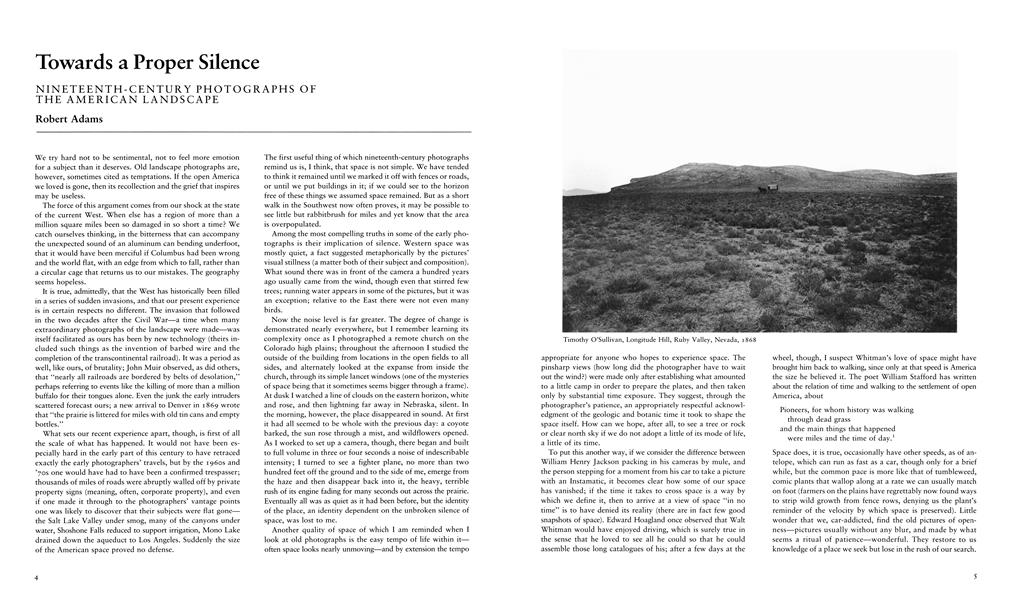

Timothy O’Sullivan was, it seems to me, the greatest of the photographers because he understood nature first as architecture. He was our Cezanne, repeatedly creating pictures that were, while they acknowledged the vacancy at the center (a paradoxical symbol for the opacity of life), nonetheless compositions of perfect order and balance. O’Sullivan’s goal seems to have been, as Cezanne phrased it, “exciting serenity.” Each was an artist/geologist, in love with light and rock.

O’Sullivan came to the convictions he expressed in his western pictures by way of experiences that must seem to us now especially relevant; he began by photographing war. Sometimes this involved taking shots of units behind the lines, like those of soldiers attached to the headquarters for the army of the Potomac, shown drawn up in ranks, and of a contingent of more than two hundred wagons and teams assembled perfectly into formation. On other occasions, however, he photographed in the midst of combat, as at Fredericksburg, or in the aftermath of combat, as at Gettysburg where he made among the most desolate pictures ever taken of war’s results. In one such view he recorded a meadow littered randomly with bloating corpses; the head of the nearest tilts toward the camera, mouth agape as if caught mid-scream, while in the distance a living officer sits placidly on his horse, forecasting the grandiose, dishonest statuary to come. Another picture shows bodies that have been dragged by a graves detail into a ragged line, a grotesque approximation of parade ground order.

Nietzsche observed that “Whosoever has built a new Heaven has found the strength for it only in his own Hell,” and this it seems to me must have been to some extent the origin of O’Sullivan’s western landscapes. More than any of the other photographers O’Sullivan was interested in emptiness, in apparently negative landscapes, in the barest, least hospitable ground (he did little with the luxurious growth in Panama, where he visited briefly). Most of his pictures are of vacancies— canyons or flats or lakes, the latter rendered as silver holes reflecting the space of the sky. In them he compulsively sought to find shape, to adjust his perspective until the plate registered every seemingly inconsequential element in balance.

The uniformity of emphasis in such pictures—the overall order, but often without a dramatic center—has recommended them to some modern photographers and painters who see the world as nonhierarchical, and who therefore themselves photograph or paint in ways that emphasize all components equally. This bias has tended to obscure, however, what was for O’Sullivan, I suspect, a different goal—to counter the leveling confusion he witnessed in battle. It is hard in fact not to see the ambulance he used to carry his equipment through the West as a metaphor, though it obviously wasn’t meant that way, for what appears to have been his wandering recovery from the disintegration he pictured at Gettysburg. Because the fact is that the landscapes he made in the West affirm with obsessive consistency an order larger than the one he saw blasted away, an order beyond human making or unmaking. The pictures themselves are human compositions, but they refer to a design that is independent of us.

Not very far in the future it may be seen that the evolution of the environment has been the major cause of the evolution of life; that a mere Malthusian struggle was not the author and finisher of evolution; but that He who brought to bear that mysterious energy we call life upon primeval matter bestowed at the same time a power of development by change, arranging that the interaction of energy and matter which make the environment should, from time to time, burst in upon the higher current of life and sweep it onward and upward to ever higher and better manifestations.

CLARENCE KING, from Catastrophism and Evolution, 1877

O’Sullivan was, from what little evidence there is, a likable, outgoing man—apparently a storyteller, notoriously profane, and respected enough by his companions to be frequently put in charge. Despite his gregariousness, however, he made people his first pictorial concern only rarely. He may not have been skilled at portraiture, but one also suspects that by the time he got to the West people did not much interest him as photographic subjects—except, and it is an important exception, as their response to nature interested him. The best picture he made at the Zuni pueblo, for instance, was not directly of Indians but of their walled gardens at the edge of the desert. And among the finest pictures he ever took were those at Canyon de Chelly, a place where people had for centuries lived harmoniously in a reserve of rock. It is interesting to recall as background for those pictures, however, what O’Sullivan surely knew as he photographed there in 1873—that in January, 1864, while the Civil War continued in the East, Kit Carson had led federal troops into the Canyon, and there killed or captured what Indians he found (they were starving and freezing) and as a final stroke, ordered the destruction of some five thousand peach trees that the Indians had lovingly tended on the canyon floor. Against these events O’Sullivan’s landscapes, which are filled with light and stillness, stand as profound meditations.

It has been suggested, mostly on the basis of O’Sullivan’s having worked for Clarence King’s surveying expedition through the West, that O’Sullivan shared not only King’s interest in the “catastrophes” recorded in western geology, but also his belief that the earth’s history is determined by catastrophes. In such a reading the pictures (which do often show geologic upheavals, as are to be seen throughout much of the West) are ominous and any divinity responsible for them is hostile.

Though O’Sullivan certainly suffered the catastrophe of the war and thus might have been attracted to the topic in general, it seems to me doubtful that the pictures of the West were taken as an indictment of the nature of life. For one thing, the pictures he made of the war’s casualties did that in a way so absolute that anything more was redundant. As for King’s influence (and to a lesser degree that of George Wheeler, O’Sullivan’s other superior in the field), presumably they did talk philosophy around the campfire, but that does not itself establish what O’Sullivan, very much his own man, believed. The pictures are the only dependable evidence we have about that, and the persistent impression they give is of calm, of stasis, which does not really accord with a philosophy of turmoil. O’Sullivan undoubtedly pictured many things at King’s request, but his treatment of the subjects suggests that the director of the project may not have understood what motivated the photographer (this kind of innocence is not unusual; Roy Stryker, who supervised photographers working for the Farm Security Administration in the 193os, had, for example, little grasp of what one of the best of them, Walker Evans, was trying to do). It is worth adding, finally, a truism from the experience of many landscape photographers: one does not for long wrestle a view camera in the wind and heat and cold just to illustrate a philosophy. The thing that keeps you scrambling over the rocks, risking snakes, and swatting at the flies is the view. It is only your enjoyment of and commitment to what you see, not to what you rationally understand, that balances the otherwise absurd investment of labor.

Whether O’Sullivan’s pictures and those of other nineteenthcentury landscapists suggest a hostile universe comes down, I think, to expectations. If we require a world designed for us, then the West they pictured is threatening, even malevolent. Alternatively, however, we can try as they did to see the landscape from a less self-centered point of view, and perhaps find in that perspective some consolation.

Admittedly the pictures do not suggest that life will turn easy. Cezanne is himself reported habitually to have remarked that “life is fearful”; Mont Sainte-Victoire was, like much of the geography O’Sullivan photographed, a pitching mountain. The wonder of the paintings and photographs is, though, that in them the violent forms are brought still, held credibly in the perfect order of the picture’s composition. Nothing is proven, but as statements of faith they strengthen our resolve to try to discover in our own lives a cognate for the artist’s vision. In the case of O’Sullivan’s vision, typified as it is finally by the intense quiet of Canyon de Chelly, we note how arduously it was earned, coming only by way of the scream at Gettysburg. O’Sullivan’s western pictures are, to borrow a phrase from Roethke, the achievement of “a man struggling to find his proper silence.”

This essay originally appeared as an introduction to Daniel Wolf’s book, The American Space, published in 1983 by Wesleyan University Press.

1William Stafford, “Prairie Town,” Stories that Could be True: New and Collected Poems (New York: Harper and Row, 1977), p. 70.

2Theodore Roethke, “In Praise of Prairie,” The Collected Poems of Theodore Roethke (New Yoríc: Doubleday, 1966), p. 13.

3It is true that many preliminary studies by Bierstadt and Moran are convincing, suggesting that part of the problem may have been the necessity of doing the finished paintings (which tended to be large) long afterward, far removed from the subject. The changes that the two made, however, were always additions in the direction of Wagnerian theatricality, and it is impossible not to conclude, when confronted by studies so uniformly better than the finished works, that the painters did not understand what they were doing; with Bierstadt and Moran we are reminded of Goethe’s observation that “genius is knowing when to stop.” Other landscape sketchers in the West, though perhaps not geniuses— men like Seth Eastman, John Mix Stanley, and Frederick Piercy—did usually content themselves with what they recorded on the scene, and thereby left us records of less ambiguous value.

4The finest landscape painter of the American wilderness in the second half of the nineteenth century, Winslow Homer, never came west, and the great realist, Thomas Eakins, visited the West only one summer, leaving as his best record of the experience two photographs of cowboys. Of the other major painters whom one supposes might have dealt credibly with the American West, Frederic Church traveled extensively but never to the West, and John Frederick Kensett, though he did get to a little west of Denver, apparently was there too briefly to understand well what he saw (his sketches are, with one or two exceptions, uncharacteristically exaggerated).

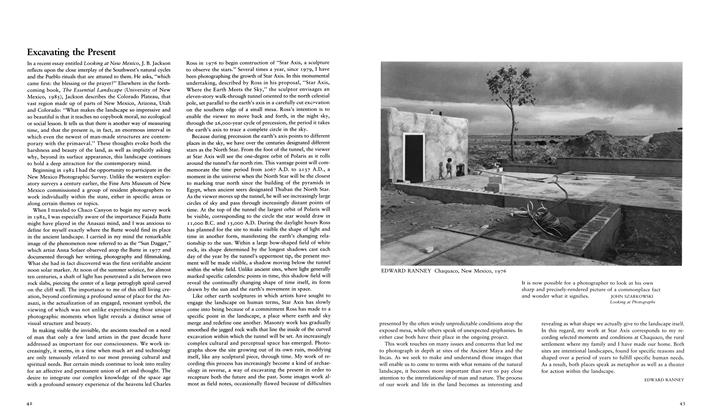

Mythology and photography both bring the sky down to earth, as it were, and focus time and light, making them, if not familiar, then less uncanny. Yet time and light clearly transcend these instruments and the humans who use them—who are left “lost” in the seemingly infinite space-time heralded by the stars. The instruments seem as much an effort to preclude a terrifying numinous experience of infinite space-time or time-light as to make finite the infinite.

DONALD B. KUSPIT, from Charles Ross: Light’s Measure, 1978

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Robert Adams

-

Our Lives And Our Children

Summer 1982 By Robert Adams -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasAn Enduring Grace: The Photographs Of Laura Gilpin

Spring 1988 By Robert Adams -

Letters

LettersLetters

Summer 1994 By Robert Adams -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasAlfred Stieglitz: A Biography, Richard Whelan

Summer 1996 By Robert Adams -

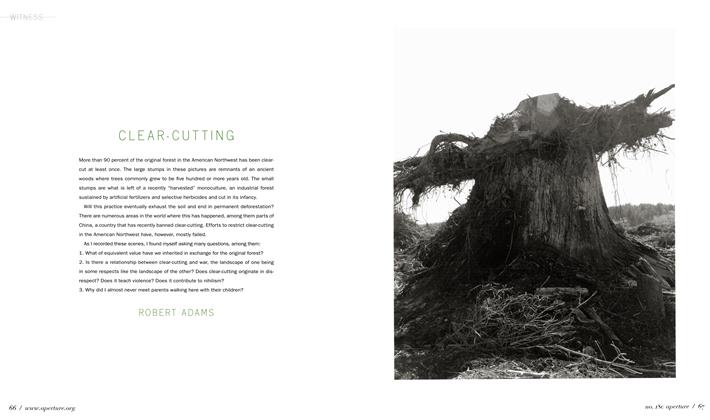

Witness

WitnessClear-Cutting

Fall 2005 By Robert Adams -

Creative Photographer

Creative PhotographerCreative Photographer

Summer 1984 By Roger Lipsey, Robert Adams