Burk Uzzle: The hustle comes of age

When Uzzle got married at nineteen in the small North Carolina town where he grew up, he photographed the story of the wedding dress, his mother and his bride-to-be meeting for the first time to sew the gown, and a $25 budget for the entire wedding. After the ceremony, a few dollars in pocket and the picture story in hand, they scratched off in a swirl of rice for an ambitious honeymoon in New York City. He had been reading Popular Photography and U.S. Camera for years, and attending summer short courses in photojournalism on Grandfather Mountain, and he was ready now to make his move. Yesterday it was Dunn, North Carolina, 3000 just folks, a tobacco town where The Charlottesville Observer and The Nashville Tennessean were the big time, or The Miami Herald and The Louisville Courier-Journal if you were particularly big for your britches. Tomorrow it would be the tall town itself and the big fellows from the city, home of old Coney Island infrared Weegee, riffraff sleeping on the fire escape, home of Black Star and Life and Magnum Photos. When the nineteen year old Uzzles zinged over the George Washington Bridge in their rented car, down and around and onto the West Side Highway, it was after midnight, which was scary enough for a couple of kids who’d been brought up to believe that the devil took over after dark, never mind all that traffic and signs that a body couldn’t make sense of even with a map. They were terrified. It was enough for a while just to keep from getting run into a concrete wall by all those loose-jointed taxis with their impudent horns. They middle-laned it all the way down, the upper west side, midtown, the lower west side, and then all the way back up on the F.D.R. Drive, the lower east side, midtown, the upper east side, and then all the way back down again on the west .... For two hours they looped the island, down the west side and back up the east, discussing the situation every ñow and then like a mature married couple, until finally they couldn’t face one another unless they at least tried to get off, pick an exit, one was as good as the next .... And so there they were, finally, in the big city, move over big city! if Dunn could just see them now! but it wasn’t the Empire State Building and Fifth Avenue on a Fred Astaire Easter Sunday, it was 125th Street and Lenox, the center of Harlem on a Saturday night—oh lawdy, they would have gladly gone back to looping if they could have found the way. At last they were standing in front of the night clerk of a midtown hotel, like a couple of kids in a Dickens novel, asking please kind sir for a place to sleep. The years have taught Uzzle that no matter where you’re headed you better act like you know where you’re going. Even now, in his mid-thirties, for all his motorcycles and hobnobbing with the high rollers on the Avenue, Uzzle, a small frail man with hom-rimmed glasses, isn’t exactly what you expect to see checking in midtown at 3:30 A.M. on a Saturday night. The clerk looked them up and down and said, you must be kidding. And they looked at one another and agreed they must be. They went back out on the street, and found their car, and got back on the highway, and got the blue blazes out of that place, getting some sleep finally in a motel in New Jersey. The next day, though, they were back in town, at the Black Star office, picture story in hand, fame and fortune calling the plays again like a sportscaster, and there they stayed, hour after hour, waiting with all the other hopefuls for someone to look at his work.

When Uzzle was twelve years old he was getting his bayonet-base SF stop-action pictures of the grade school basketball games published in the local paper. The fantasy then was a 4 x 5 Speed Graphic with a Graflex flash gun, your pockets bulging professionally with Press 40’s, a backup pack of Super XX and a backup set of D cells in a work-worn vulcanite case, gray with black hardware, with your work-worn name and affiliation stenciled on top, the shutter release on the lens board mounted at a fetching angle. He manned the photo machine in the bus station in the days before it was fully automated; he worked for the local newspaper and the local studio, going from house to house on a bicycle with a Rolleicord, $1 for a glossy 8 x 10, carrying the vulcanite case in the bike basket, a perfect fit. He learned when to wait and where, and how to move when the time came; when the next fantasy shaped up, when the hustle was on.

Hour after hour, day after day, the Uzzles spent their honeymoon in the Black Star office, fewer dollars in the pocket each day, waiting amid all the cigars and ringing phones, shoulder to shoulder on the bench against the wall with all the other hopefuls in all the other offices of all the other talent brokers all over the world, virtually all of them on their quick way to stacking trays in Horn & Hardardt and then on back home to become the presidents of the local camera clubs and to reminisce the rest of their lives about New York and the Black Star office. Finally somebody looked at Uzzle’s pictures, which is all it has usually taken, and in the happy end he paid for his honeymoon with pictures of his wedding. A few months later he was under contract with Black Star, and a few years later he was a Life staffer, and a few years after that he was proffered an invitation to join Magnum, that honey of all moons to young photojournalists who took their readings in the shadow of Cartier-Bresson. For every ten thousand photographers who want to join Magnum, one gets the chance; for every ten who get the chance, nine jump at it. Uzzle hung back for a couple of years; he was accustomed now to being the one, not the nine out of ten; in 1967 he became a member of Magnum, and still is.

The photography scene, as most of us know only too well, is chock full of intense paranoia, and its attendant isolation. There are little groups huddled together bad-mouthing one another, suspicious and compulsively defensive. Those who refuse to be pinned down in any little comer of it—like Davidson, and Friedlander, and Harbutt, and Uzzle—are especially important to us all. Uzzle is equally at home in the Witkin Gallery and on the Avenue, in Aperture and on the cover of Newsweek, as comfortable thinking and talking as most photographers are being pointedly silent. Fie is free, as very few of his professional colleagues in New York are, to think that Jerry Uelsmann’s work might very well turn out to be more important than all Magnum’s put together, Cartier-Bresson excepted, and at the same time, as few of Uelsmann’s admirers are, to believe that Philip Jones Griffiths’ Vietnam Inc. is more valuable than all but the best of the fancy camera work and printmaking that has accompanied the exhaustion of photojournalism.

Among those he works with in New York—the photographers, the art directors, the editors, the agents—Uzzle has the reputation of a professional among professionals. One of his colleagues in Magnum, a man who has proven many times over his instinct for being in the right place at the right time, tells what it’s like for a photojoumalist to work elbow to elbow with him: they both appeared in Memphis when Martin Luther King was assassinated and ran on the story together for three days without sleep. When he got back and looked at his proof sheets, Uzzle was in nearly every picture he took. When the floor beneath that kind of photography began to give way, eventually dropping Life magazine itself into the rubble, a lot of photographers who had grown up on the streets had to find other ways to make a living. One of Magnum’s responses was to cultivate the world of annual stockholders’ reports, to sell the likes of Elliott Erwitt or Bruce Davidson to RCA for $750 to $ 1,000 a day so that it would be possible to photograph East 100th Street whether or not anybody wanted to buy the pictures. Uzzle had never done industrial photography, and he wasn’t one of the first Magnum photographers to try, but when he did it was the old honeymoon story all over again: he stood around long enough for somebody to look at his work, and a year later he was out in front, the first thing you saw when you got around the comer. If Magnum wants to sell somebody besides Uzzle to a potential new client now, they don’t show Uzzle’s portfolio.

There are a lot of people running around wearing different hats, but very few who can keep their head in the same place underneath them all. Uzzle can photograph motorcycle freaks one day and the board of directors of Merrill, Lynch the next not because he has a knack for moving among mutually exclusive worlds but because he sees them all as part of the same thing. Coming down off Grandfather Mountain, he might have looped the twentieth century a few times before he landed, but once he put down he knew exactly where he was and what he wanted to do with that knowledge. Uzzle has an almost Fulleresque love of technology, the sort of feel for computers and chrome and steel that we ordinarily associate with the hand crafts. Let the freaks and the directors fight if they must, he’s not much interested in their argument, or anybody else’s. For all his competitiveness, Uzzle isn’t the least bit contentious, not now anyway, quite the opposite, in fact, gracious, generous, unassuming in spirit as well as manner, a fine charm and sense of proportion to him; he has the moves of a man very much in command of himself and his life. Instead of writing industry off as his bread and butter, which can be a tricky kind of bookkeeping, treacherous at times, he sees in it an entree into a world that he is all the wiser for knowing, and that, from time to time, hands him personal satisfaction along with his livelihood. His Sun City pictures, some of which are in his first book, the recently published Landscapes, sprang full-blown out of the unlikely head of a bunch of financiers. As part of an annual report he drove around a southern California development with them, listening to them analyze the community, and returned immediately when the assignment was done to photograph the place through their eyes, a series of hard-edged acerbic pictures that cut through to the very gizzard of a world seen as stocks and bonds. When he has to wrestle with his life, he does it, it would seem, like a Judo master. He takes the weight of what is thrown at him and uses it to his own ends; where others struggle, he dances.

If the one head is essential to what Uzzle is about, so too are the many hats; that’s the way his circuit is wired, the way his juices flow. He has a Protean appetite for change, seems to thrive on it. A lot of adventurousness is predicated on stability back home, wherever or whatever home is. It may be family, place, God, previous accomplishments, usually, in the end, an unflappable confidence in one’s instincts. When Uzzle turned away from his early journalism in mid-success in search of a more sophisticated image of the social landscape, those around him shook their heads and called the move a mistake. When he turned away from the social landscape in mid-success to fiddle with set-ups of styrofoam and industrial gewgaws in a studio, he got the same reaction, even more so—imagine a Cornell Capa or a Marc Riboud looking at pictures of white on white! And now, as the large-format work begins to be taken seriously, he is back out on the streets with the Leicas, and some of the same people are telling him all over again that he is making a mistake.

For all his passion for photography as photography, the black Leicas in loving hands, miniature homemade blue denim duffle bags for carrying film, the archival prints in the clear plastic sleeves in the museum boxes, photography has never been an end in itself for Uzzle. Early on, in the days of the summer short courses in the south and the assignments as a staffer for Life, it was not only a livelihood but a way to go places and do things. The sexy old press pass to where the action is skipped him brilliantly across the surfaces of the world. As he matured and came into the awareness of an inner life, he grew tired of just going to those places and doing those things, and photography became a way of articulating his spiritual life, a way to stop skipping and go deep, a ritual spread like foam on the surface where he dove.

Uzzle’s career over the past ten years or so is a paradigm of much that has happened in serious photography in this country—which in turn reflects many of the important changes in the culture at large. When Robert Frost delivered a poem at Kennedy’s inauguration, we were still looking to public life and to institutions for much of our nourishment, if not our salvation. Then the Bay of Pigs, and the missile crisis, and the assassination, and the war, and more assassinations, and more war, and Kent State, and Nixon. ... As think little was replacing think big as a habit of mind, home rule undercutting the sprawling bureaucracies, as The Whole Earth Catalogue was replacing the Civil Defense Manual as a check list for our survival kits, as Richard Alpert was spinning through drugs on his way to becoming Baba Ram Dass, as dumb Indians were turning out to be wiser than the think tanks, as we were beginning to listen to our bodies instead of our psychiatrists, as we were becoming more interested in art (in news that stays news, as Pound puts it) than The New York Times, the Uzzles moved from the city to the country, fixed up an old farmhouse not far from Woodstock, New York, and Uzzle stepped completely outside the long shadow of Cartier-Bresson, the public world of decisive moments, the small camera and the quick move, into the lights of his own new studio, private arrangements and a different pace. The anecdotes of his earlier social commentary, built around associations that were often verbal, or at least verbalizable, gave way to imagery that had little or no paraphrasable content—which, when it worked, got well beyond an interest in the purely visual into the tilts and swings of the psyche itself. And now, as the country purges itself by cleaning out the government, Uzzle is back on the public scene, a Proteus flying by the seat of his pants, the new hand-held work showing clearly the influence of the studio. It is a much quieter, more introspective thing he does now; the associations he is making are no longer characteristically anecdotal, but visual and plastic. Perception is replacing statement; where once he was a heavy hand and a belly punch, now he floats in the vapors of things—in his words, “a journalism of the spirit.”

The story of the sea god Proteus suggests an interesting way of looking at a career such as Uzzle’s. Sometimes known as Poseidon’s son, other times as his attendant, Proteus had the power to change forms at will, a man one minute, a monster the next, a story close to the heart of an anxious, uncertain and insecure age. If you can stand all the quick changes, so the story goes, if you can hang in there with Proteus without demanding that he be one thing or another, he’ll quiet down after a while and tell you what you want to know. It is a very rich and profound story about the illusory nature of the material world, about energy and change, about knowledge, about patience, about two radically different views of the world fused into one act .... Proteus is not only the nervousness of the twentieth-century materialistic west, checking the doors every few minutes to make sure the escape routes are open, the mode of reason and wit and irony and artifice, he is also at the same time the powwow doctor in his dance, the One running through its manifestations as the Many.

According to the story, Proteus has yet another power. He foretells the future. Much as Cartier-Bresson’s work is haunted by the past, a European chamber music of the eye, Uzzle’s is haunted by the future—and, his love affair with technology notwithstanding, haunted is the right word—a landscape so divorced from earth, air, water and fire as to seem almost lunar at times, a world so wired to efficiency that nothing is admitted into it that can’t be controlled. Over and over again he tells us that although the superhighways and computers sing, we may become captives of mechanical dreams which are foolish at best, at worst utterly dehumanized and sterile. Uzzle is good enough, and Landscapes is coherent and purposefully U.S.A. enough, to call to mind The Americans. People are at the heart of Frank’s world, their surroundings an extension of or a comment on their inner lives, whereas in Uzzle the landscape is the thing, the people, in most of his pictures, merely a function of it, like the figures that indicate the scale on a geological map. The humanist would hope that the differences are between two points of view, not a change that has occurred in the country at large in the years between the two books.

As an artist Uzzle’s signature is in part his theme, in part the consummate, at times exhilarating authority of his execution. With the exception of his romantic soft-focus pictures of the hard-edged world of chrome and steel and bike-riders, and some of the large-format work, he hasn’t innovated so much as refined and perfected and extended. Even when he is showing his sources—Cartier, Kertész, a touch here and there of others—what you see is how good he is. Or how good he is. Uzzle is a virtuoso, and like many virtuosos he justifies his use of others with the sheer command of his performance. And part of his signature, a large part, comes from that uncanny knack he has for boldness and delicacy in the same stroke. So characteristic, and so convincing; it sorts down to the theme of all his themes, what really moves him. It is probably there that he is making the artist’s inevitable self-portrait, saying something again and again, perhaps, of what it is like to be a frail North Carolina bicycle boy given to bold moves in the world, wheelies amongst the music of the industrial spheres.

His signature as a man is his self-confidence. Coming off Grandfather Mountain on a bicycle, wideeyed and bushy-tailed and moving fast, is a great approach to the wide world if you don’t crack up on contact. It is a lot easier to maintain innocence and enthusiasm for life than it is to achieve it. Uzzle knows what it is like to be a winner, but he might have to learn to lose as well if he wants to take that final turn to ripeness. No matter who gets around the corner first, the dark forces are there waiting, a knowledge which is only begining to appear in his work. Still, his confidence stands strong in mid-career.

A couple of years ago Uzzle took up motorcycles, and he and his sons have been riding trail bikes lately in the meets. The bike thing isn’t cut throat winner-takeall, for there is a wonderful mystique that surrounds it, a copy of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and a lot of beautiful father-and-son stuff, but the growing number of trophies in the house bear witness that the competitor in him is still kicking. The hustle gets you only part way, and he knows that. Competitiveness might be the way of some worlds, but if a work of art spins off from that spirit, it is because something finer is also there. You can court the muse, and probably have to if you want her to notice you but you damn well better not go trying to wrestle her to the floor. If you want to dance with the powers, you have to follow their lead. In Uzzle’s words, “Photography used to be something you could do with your legs, but now you have to do it with your head and heart. ” And the true heart doesn’t bend to anyone’s will. About all you can do, Uzzle would say, is blow cool camera, let it happen, and see what comes out.

James Baker Hall

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

James Baker Hall

-

Ralph Eugene Meatyard

Summer 1974 By James Baker Hall -

Song Without Words

Winter 1978 By James Baker Hall -

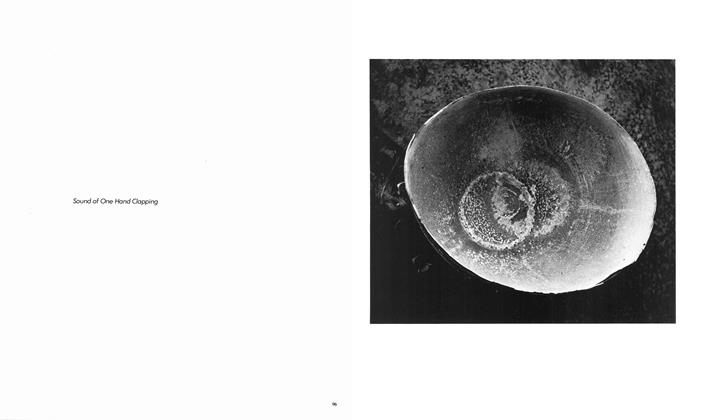

Sound Of One Hand Clapping

Winter 1978 By James Baker Hall -

Postscript

Winter 1978 By James Baker Hall -

Emblems & Rites

Summer 1974 By James Baker Hall, Guy Davenport -

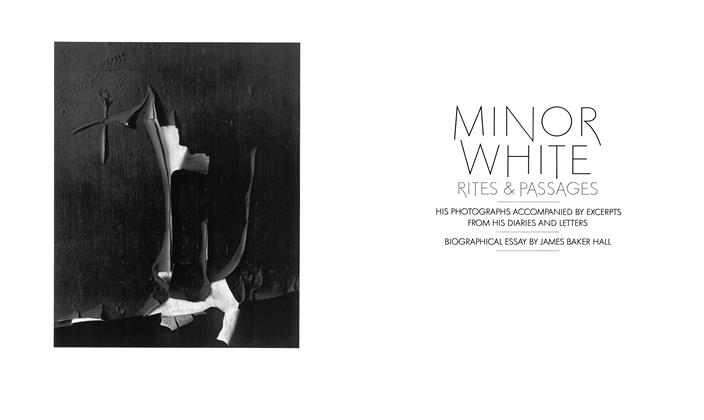

Minor White: Rites & Passages

Winter 1978 By James Baker Hall, Michael E. Hoffman