The Camera and Dr. Barnardo

Alan Trachtenberg

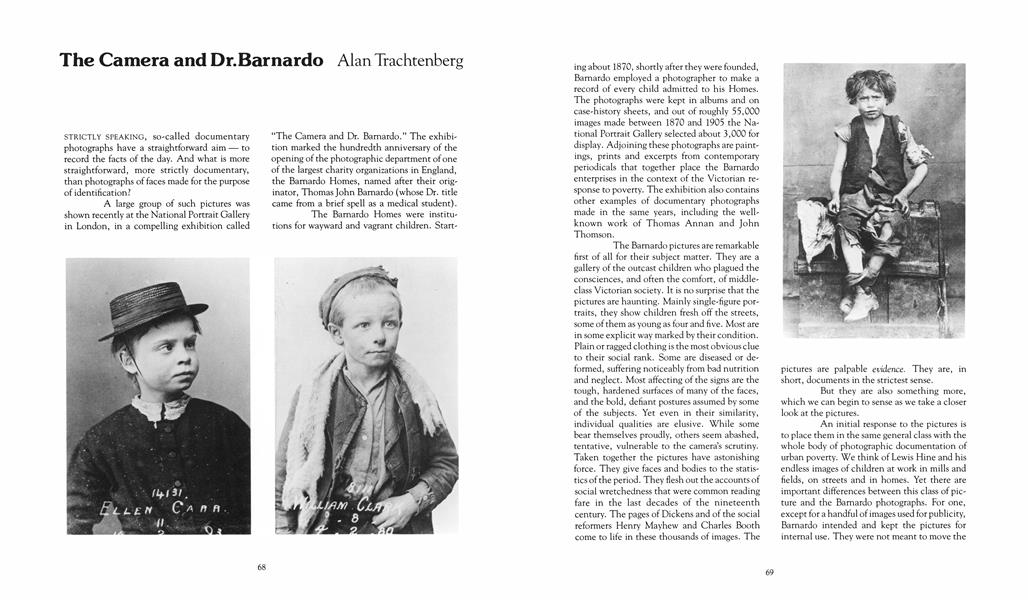

STRICTLY SPEAKING, so-called documentary photographs have a straightforward aim — to record the facts of the day. And what is more straightforward, more strictly documentary, than photographs of faces made for the purpose of identification?

A large group of such pictures was shown recently at the National Portrait Gallery in London, in a compelling exhibition called “The Camera and Dr. Bamardo.” The exhibition marked the hundredth anniversary of the opening of the photographic department of one of the largest charity organizations in England, the Bamardo Homes, named after their originator, Thomas John Bamardo (whose Dr. title came from a brief spell as a medical student).

The Bamardo Homes were institutions for wayward and vagrant children. Starting about 1870, shortly after they were founded, Bamardo employed a photographer to make a record of every child admitted to his Homes. The photographs were kept in albums and on case-history sheets, and out of roughly 55,000 images made between 1870 and 1905 the National Portrait Gallery selected about 3,000 for display. Adjoining these photographs are paintings, prints and excerpts from contemporary periodicals that together place the Bamardo enterprises in the context of the Victorian response to poverty. The exhibition also contains other examples of documentary photographs made in the same years, including the wellknown work of Thomas Annan and John Thomson.

The Bamardo pictures are remarkable first of all for their subject matter. They are a gallery of the outcast children who plagued the consciences, and often the comfort, of middleclass Victorian society. It is no surprise that the pictures are haunting. Mainly single-figure portraits, they show children fresh off the streets, some of them as young as four and five. Most are in some explicit way marked by their condition. Plain or ragged clothing is the most obvious clue to their social rank. Some are diseased or deformed, suffering noticeably from bad nutrition and neglect. Most affecting of the signs are the tough, hardened surfaces of many of the faces, and the bold, defiant postures assumed by some of the subjects. Yet even in their similarity, individual qualities are elusive. While some bear themselves proudly, others seem abashed, tentative, vulnerable to the camera’s scrutiny. Taken together the pictures have astonishing force. They give faces and bodies to the statistics of the period. They flesh out the accounts of social wretchedness that were common reading fare in the last decades of the nineteenth century. The pages of Dickens and of the social reformers Henry Mayhew and Charles Booth come to life in these thousands of images. The pictures are palpable evidence. They are, in short, documents in the strictest sense.

But they are also something more, which we can begin to sense as we take a closer look at the pictures.

An initial response to the pictures is to place them in the same general class with the whole body of photographic documentation of urban poverty. We think of Lewis Hine and his endless images of children at work in mills and fields, on streets and in homes. Yet there are important differences between this class of picture and the Bamardo photographs. For one, except for a handful of images used for publicity, Bamardo intended and kept the pictures for internal use. They were not meant to move the public, but were consigned to the record books of the Homes. For another, documentary photographers like Thomson and Jacob Riis and Hine, who presented their work to the public, usually accompanied their images with explanatory texts, detailed its important features and often indicated how the photographer felt about the subject. The photographs were part of a general investigation. By contrast, the Barnardo pictures were simply meant to be likenesses. If they now move us to empathy or pity or outrage at the social system, this was not their original aim, and they do it without the rhetorical elements—either in the picture or in an accompanying text—employed by the photographer-investigators.

Our impulse to place the Bamardo pictures within a larger documentary tradition stems from the historical association between the term “documentary” and pictures of the poor, the downtrodden, the outcast. That association reveals much about the role documentary photography has played in reinforcing one of the major ideas about modem life, that society is profoundly divided in economic terms. But when we compare the Bamardo pictures to the more familiar documentary work of Riis and Hine, we see that these faces are not simply factual images of a suffering underclass. The message of the pictures is more complex (as, indeed, may be the category of documentary itself). They are not only mug shots.

Though each picture contains the name and number of the child it shows, this information does not exhaust its meaning. Something more than the mere identification of physiognomy appears.

Upon inspecting the pictures, the additional qualities derive from the fact that the dominant photographic convention they utilize — and it is appropriate to refer to it as a convention, established through the previous two decades of Victorian photography—is that of the studio portrait. These are posed pictures, made with a measure of collaboration between sitter and photographer, in an enclosed photographic space defined by certain props and background. The poses are often familiar: body draped over chair, arms folded, three-quarter view. There is little of the stark frontality of the early police photographs that the exhibition displays alongside the Bamardo collection. Even in the Barnardo pictures made in the years before the photographic department began in 1874, with the children usually in the open air, posed against walls or among odds and ends of the street, there is the mark of the studio portrait. They are carefully composed, the child placed artfully to occupy most of the frame, often to convey the impression of having been just found in a natural habitat.

In the typical commercial situation the studio portrait is a willing collaboration between sitter and photographer. The studio allows the sitter a special space within which to compose himself into an expression, a picture, that approximates his own as well as his society’s ideal. In effect, the sitter becomes his pose, self-enhanced in that one moment he believes will last forever. The entire experience is momentarily eternalizing. The portrait is variously an extension of being, an aggrandizing act against time, an assertion of a role the sitter wishes to play.

Needless to say, these were not the conditions that obtained in the Bamardo pictures, for all that they utilized similar pictorial conventions. To itemize the obvious: The children were not customers. They had no friends or family who might welcome a picture, and it is likely that many of them never even saw their own pictures. The picture-making situation existed primarily for identification, and the children were not encouraged to efface themselves into a timeless pose. If anything, especially in the earlier pictures which were meant for publicity, they were encouraged to perform as poor, suffering children—that is, to exaggerate the truth about themselves in order to transform that truth into a pictorial role.

In any case, the result is that while the studio convention used in these photographs makes them more than documentary, the inappropriate use of convention makes them less than full studio portraits. As records the pictures tell us too much, because the studio mode allows the child room for more individual expression than necessary; yet as portraits they seem incomplete, reticent, as if the sitter wants to withhold more than he reveals. The pictures exude an unsettling ambiguity. They seem to approach yet fall just short of an unbearable revelation.

Such a pervasive contradiction between function and mode in an entire body of work is, I believe, a unqiue event in photography. How is it to be accounted for? The answer seems to lie in the values of the institutional structure that created this ambivalent gallery of faces in the first place. If the pictures exceed the strict and narrow sense of documentary, if they are more or less deliberate inventions of meaning, then their meaning and their history are intimately associated with the institution that made them, the Bamardo enterprise.

To the comfortable classes in Victorian England, the poverty-stricken had only simple needs: to be cared for, body and soul. Their plight seemed a natural outcome of simple causes: their refusal to work, their prostitution, drink and general depravity. The Christian charity movements in the 1860’s and 1870’s attempted to recruit middleand upper-class support for their sundry activities on the grounds that the better classes, being morally superior, might have a benign effect on the poor, who suffered as much from bad morals as from empty pockets. Moreover, the better classes would help themselves in subtle ways by charitable giving — for charity would confirm the superior position of the privileged, thus maintaining the social distance between giver and recipient.

Thomas John Bamardo was a prominent figure in these charity enterprises. He began his work in the late 1860’s, when the situation of the poverty-stricken had grown menacing. Large numbers of unemployed and casual laborers had demonstrated against their conditions, and the contingent of beggars, including children, had increased on the streets. Bamardo was a vigorous go-getter, a shrewd and determined entrepreneur on behalf of his Homes and missions. His activities were financed entirely by private contributions; he had no explicit interest in the political system nor in crusading for social reform. His passion was not to eliminate poverty but to save the young. His appeal was to conscience, and he flooded the nation with pamphlets, issues of his journal, Night and Day, and collection boxes adorned with photographs of deprived children.

In his copious writings, he describes himself as a “warrior-evangel,” fishing among the “wastrel children of the slums” where “it has been my delight to set traps by which I might catch the wandering feet of little homeless waifs who were vagrants, and were in the custody of beggars or people of evil who would in all likelihood have degraded and ruined them.” He speaks of his own “tender violence” in rounding up homeless children from dark alleys or lodging houses. The children were innocents, and he was their salvation.

“I don’t quite know what it is that makes children so attractive to me,” he wrote, “but although I have had many who have been crippled and sadly deformed, and some who have been afflicted with very dreadful disorders, I think I may say of a truth that I have never seen a really ugly child! There is always in my mind something beautiful in the little ones, however disfigured they may be with sin and suffering, something that looks out of their young eyes and half-formed features, and that pathetically appeals to one’s pity and sympathy and love — something, too, that fills one with reverence for childhood.” But Bamardo also expressed the obverse of the sentimental vision: children are often “as wild as the proverbial March hare” and difficult to keep in hand. In short, they require a mixed feeding: reverence for their angelic innocence, and stem discipline for their demonic outbursts. This, in essence, was Bamardo’s formula for dealing with the double-natured children in his care.

The formula was a recipe for moral transformation, and it is no surprise that Bamardo’s earliest use of photographs was an attempt to make visible the transforming effect of his Homes. His first published pictures were before-and-after shots of children, first in the state of raggedness and despair, then cleaned up and happily at work at a trade. These paired images appeared in pamphlets or as pairs of cards, sold in sets to the public on which Barnardo counted for support. “Once a Little Vagrant” and “Now a Little Workman” is a typical set. These before-and-after sequences were based on an astute recognition of the innate power of the camera to convey a narrative message, and, in sequential images, to make the passage of time seem concrete, dramatic and palpable. They may be the earliest appearance of this device, which was to become so common in advertising. The particular narrative implied in these sequences accorded perfectly with the moral views of the charity movement: that appropriate institutional care led to the salvation of the poor. In these compositions the viewer is not obliged to discover a visual meaning but only to recognize a visual equivalent of an ideology he is already presumed to possess. (In this characteristic too, in the ease and immediacy of the communication, the device anticipates the common rhetorical patterns of advertising. )

The images were in fact staged, sometimes extensively, and in 1876, when several charges were brought against Bamardo by a rival clergyman for alleged misconduct and misuse of funds, the pictures were part of the accusation:

The system of taking, and making capital of, the children’s photographs is not only dishonest, but has a tendency to destroy the better feelings of the children. Bamardo’s method is to take the children as they are supposed to enter the Home, and then after they have been in the Home some time. He is not satisfied with taking them as they really are, but he tears their clothes, so as to make them appear worse than they really are. They are also taken in purely fictitious positions. A lad named Fletcher is taken with a shoeblack’s box upon his back, although he never was a shoeblack . . .

Before an arbitration court Bamardo conceded occasional falsifications in the pictures. (He also conceded other charges of floggings and solitary confinements, which the court allowed were justified.) Yet he defended the falsifications as legitimate because the pictures represented a class of children: . very many photographs are representative or typical, i.e. not intended so much to represent the individual boy or girl whose face is depicted, but a WHOLE CLASS of street children of whom very many have been rescued.” The language of Bamardo’s defense is curiously anthropological, as if the children represented a separate species.

The purpose of a photograph, Barnardo argues, is to convey an accurate picture of a creature in “its real and habitual state from which we sought to rescue it.” In order “to illustrate this CLASS and their condition, we are often compelled to seize the most favorable opportunities of fine weather, and the reception of some boy or girl even of a less destitute class, whose expression of face, form, and general carriage may, if aided by suitable additions or subtractions of clothing, and if placed in corresponding attitudes, conveys a truthful picture (because it is typical) of the class of children received in unfavorable weather, whom we could not, for the reasons given, photograph immediately.” Even taking into account the common sophistry of legalistic argument (“suitable additions and subtractions of clothing”), the statement reveals an interesting unconscious motive, which is to submerge the individuality of the child within the illustrative trope of the “class.”

The court’s response to the defense helps, in fact, to clarify the presumptions of the defense. The judges ruled against Bamardo in this instance (though generally clearing him of the most serious charges) by condemning his use of “artistic fiction” in material that passes as photographic, that is, factual, illustration. Barnardo himself had invoked the authority of Art in his defense, citing the art-photographs of Rej lander and the paintings of B. S. Marks as precedents for using individuals to depict classes. In effect, the court conceded that the staged images were “artistic,” but ruled against them precisely because they were. “Artistic fictions” were legitimate in works that presented themselves as “art,” but not in works that appeared before the public as faithful records of fact.

Bamardo was caught in a dilemma arising from photography itself. His use of the admittedly faked images rested on the unspoken assumption that the public accepted photography in the manner of Lady Eastlake ( 1857): a “sworn witness of everything presented to her view.” Thus the public would accept as literally true anything that appeared before it as a photograph. Now, this power to transcribe the literal was precisely what many artistic photographers attempted to overcome—in the case of Rejlander, by building up single images out of multiple negatives in pictures with allegorical themes, of which “Two Ways of Life” (1857) is the most famous. Bamardo’s argument is a wish to have it both ways: the staged or artistic was also to be accepted as the literal and true. At a deeper level, moreover, he seems to have wanted to maintain some aura of art (or typical representation) as a way of controlling the images projected by the children, a way of stage-managing them to conform to the ideological statement. This is not to say that he personally feared a direct image, unmediated by any sentiment or fiction of art; his recognition of what constituted a picture of his children was limited by his — and his culture’s — preconception of what the “type” of poor, ragged street waifs looked like. The notion of an artistic fiction, in this instance then, was a way of controlling the image, of keeping its meaning safely within the bounds of recognized and accepted sentiment.

Barnardo abandoned the outright fictions of the before-and-after pictures; yet what are the studio conventions he then employed in the bulk of the album pictures but another effort to control, to impose pictorial values drawn from a social tradition of portraiture? Of course, merely to pose the children and provide meager props in order to pictorialize their image is hardly a malicious method of control — insofar as they were conscious, the motives, in fact, are strictly aesthetic rather than social. But cultural values express themselves most potently in behavior that does not require conscious thought.

It may be only a coincidence that in the full statement to the court in which Barnardo described his intentions in employing photographs, he stressed precisely their usefulness for control. Coincidence or not, his words are revealing. Apart from the propagandistic purposes of “advocating the claims of our Institution . . . with the Christian public,” the photographs had two other functions. One was “to obtain and retain an exact likeness, which being attached to a faithful record in our History Book of each individual case, shall enable us in future to trace every child’s career.” The other function suggests the “trace” the Homes might want to undertake: “to make the recognition easy of boys or girls guilty of criminal acts. . . . Many such instances have already occurred in which the possession of these photographs has enabled us to communicate with the police, or with former employees, and thus led to the discovery of offenders. ” The pictures were useful, too, in locating “children absconding from our Homes,” or recovering those “who have been stolen from their parents or guardians, or were tempted by evil companions to leave home.”

What crowds into these words is the uneasy feeling that children caused deep insecurity in the period. They were potential criminals, even if also potential workers. Moreover, they were property; they belonged to someone, and the photograph could be used as proof of ownership. In this connection it is enlightening to learn that illegal detention of children was another charge raised against Bamardo, one that the court overruled on the grounds that the Homes had the moral right to remove children from improper parents.

If the stated intention of the pictures was to serve as dossier photographs, mere identification shots, then why the studio motifs, the concessions to convention? One answer might be that the convention of the plain dossier photograph had not yet taken hold. But the factual dossier picture would not represent as faithfully the complex attitudes of the Bamardo Homes toward their wards. The pictures are inescapably ambiguous and contradictory because that, in fact, was the nature of the relations between the children and the Homes.

The children had no choice but to sit; it was part of the admission process. In one picture in the exhibition, a young boy turns his back and remains recorded in that ultimate refusal to be seen. But most complied, arranging themselves as directed before the camera. Smiles are scarce and faces are solemn masks. Occasionally we encounter a genuine collaboration between sitter and photographer, a meeting of eyes that fixes our own gaze back at the revealed truth of a person. Yet on the whole the sitters are not comfortable. Their freedom to make their own statement is incomplete, denied as much by their social and cultural deprivation as by the photographers conventionality. Why are they being photographed? And how are they supposed to look, to present themselves? Neither sitter nor photographer seems able to overcome the gulf implied by these questions, which in turn derive from the institutional situation within which the photographic transaction occurs.

The children deliver themselves, but tentatively, in some cases defiantly, in most cases begrudgingly. What they are delivering themselves to is an idea of a picture which corresponds to the idea embodied in their situation: that they are outcasts who require transformation into useful citizenship. The pictures will touch them with a respectability that they have not yet attained. In a profound sense these are threshhold photographs, made at the beginning of a new phase in the lives of these small figures gathered from the streets. The children clutch their individual histories to themselves, as if aware that something will be taken from them in exchange for the image they are about to surrender to the camera.

Now that we can see these photographs in a gallery, isolated from their original function, they magnetize our attention in a curiously affecting way. They continue to hold us because they say so little about the individual children yet at the same time so much about their collective predicament. Their power is paradoxical; they are affecting because of the absence of the deep visual encounters we expect from major portraits. Instead of the commanding eye of an artist, the most palpable presence in the pictures is Bamardo’s “tender violence,” sentimentality linked to a vigorous authoritarianism. From that fundamental contradiction comes the pictorial values which govern the images.

The lesson of the Bamardo pictures is that photographs have histories intricately embedded in their structures, in the icons they employ, in the point of view they establish. How different these pictures might have been if the photographer had practiced a strict frontality, even within the studio format. The pictures represent choices which in turn represent values and ideologies. And what are pictorial values themselves but visual equivalents of cultural values? The strictest documentary photograph has within it some notion of picture-making, which is also a stance toward the world. ■