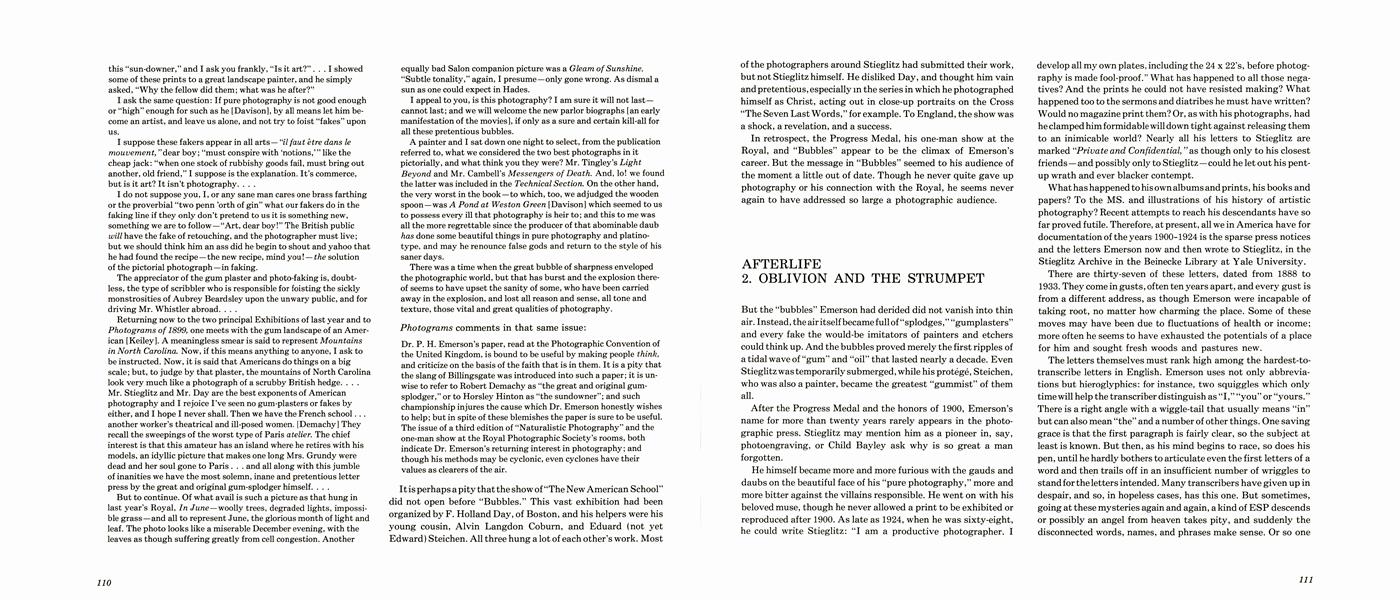

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine Art

Afterlife 2. Oblivion And The Strumpet

Spring 1975 Nancy NewhallAFTERLIFE 2. OBLIVION AND THE STRUMPET

But the "bubbles" Emerson had derided did not vanish into thin air. Instead, the airitself became full of "splodges,""gumplasters" and every fake the would-be imitators of painters and etchers could think up. And the bubbles proved merely the first ripples of a tidal wave of "gum" and "oil" that lasted nearly a decade. Even Stieglitz was temporarily submerged, while his protégé, Steichen, who was also a painter, became the greatest “gummist” of them all.

After the Progress Medal and the honors of 1900, Emerson’s name for more than twenty years rarely appears in the photographic press. Stieglitz may mention him as a pioneer in, say, photoengraving, or Child Bayley ask why is so great a man forgotten.

He himself became more and more furious with the gauds and daubs on the beautiful face of his “pure photography,” more and more bitter against the villains responsible. He went on with his beloved muse, though he never allowed a print to be exhibited or reproduced after 1900. As late as 1924, when he was sixty-eight, he could write Stieglitz: “I am a productive photographer. I develop all my own plates, including the 24 x 22’s, before photography is made fool-proof.” What has happened to all those negatives? And the prints he could not have resisted making? What happened too to the sermons and diatribes he must have written? Would no magazine print them? Or, as with his photographs, had he clamped him formidable will down tight against releasing them to an inimicable world? Nearly all his letters to Stieglitz are marked “Private and Confidential, ”as though only to his closest friends—and possibly only to Stieglitz—could he let out his pentup wrath and ever blacker contempt.

What has happened to his own albums and prints, his books and papers? To the MS. and illustrations of his history of artistic photography? Recent attempts to reach his descendants have so far proved futile. Therefore, at present, all we in America have for documentation of the years 1900-1924 is the sparse press notices and the letters Emerson now and then wrote to Stieglitz, in the Stieglitz Archive in the Beinecke Library at Yale University.

There are thirty-seven of these letters, dated from 1888 to 1933. They come in gusts, often ten years apart, and every gust is from a different address, as though Emerson were incapable of taking root, no matter how charming the place. Some of these moves may have been due to fluctuations of health or income; more often he seems to have exhausted the potentials of a place for him and sought fresh woods and pastures new.

The letters themselves must rank high among the hardest-totranscribe letters in English. Emerson uses not only abbreviations but hieroglyphics: for instance, two squiggles which only time will help the transcriber distinguish as “I,” “you” or “yours.” There is a right angle with a wiggle-tail that usually means “in” but can also mean “the” and a number of other things. One saving grace is that the first paragraph is fairly clear, so the subject at least is known. But then, as his mind begins to race, so does his pen, until he hardly bothers to articulate even the first letters of a word and then trails off in an insufficient number of wriggles to stand for the letters intended. Many transcribers have given up in despair, and so, in hopeless cases, has this one. But sometimes, going at these mysteries again and again, a kind of ESP descends or possibly an angel from heaven takes pity, and suddenly the disconnected words, names, and phrases make sense. Or so one hopes ; it will surprise no one who has attempted these transcriptions to find a later, clearer reading—or that it was certainly no angel who inspired that “translation.” Traduire c’est trahir: “To translate is to betray”—an axiom among those seldom appreciated, highly dedicated people called translators.

This brings up the question of who was his amanuensis in those days of no dictating machines and few typewriters? Who made readable that great spate of articles and books? Someone, certainly, who knew him and his handwriting well and was close enough to ask questions. His wife? She must have coped with her father’s hand, and, as a Grey Sister, with those of other doctors.

Did she begin with his first book, written during their honeymoon, Paul Ray at the Hospital? Lacking her or whoever it may have been, future transcribers might do well to consult a pharmacist or druggist—or, in British, a chemist or apothecary.

The letters tell us little about what Emerson was doing; they tell us how he felt. And, as noted before, we do not yet have Stieglitz’s replies in his own calligraphy, one of the most beautiful and powerful in the history of handwriting. The one letter in the Beinecke from Stieglitz to Emerson was typewritten, and therefore we have still a carbon.

To understand these letters, of which we have only Emerson’s side, we must attempt to understand the curious relation between the two. Emerson had discovered and acclaimed the young Stieglitz, true. (By the way, he was only eight years older than Stieglitz.) Stieglitz was to go far beyond him into seeing life through photography and art, yet still Emerson had gone before him, calling for “truth to Nature, ’’for the unconscious, natural pose, for the moment when light, landscape and the activities of men fused together, or when a cloud, a tree, a house, a face was suddenly revealed as a symbol of human experience. In exhibitions, again, Emerson went before him, insisting on beautiful prints on fine paper, simply framed — and if the prints were not worthy of hanging on “the line,” why hang them at all? Publications the same: fine platinum prints carefully printed, mounted on good paper and protected by delicate tissue, or gravures made under the photographer’s eye, equal to original prints in the opinion of both, and many others. Emerson learned to photoengrave, set up his own press and printed his last books himself. Stieglitz became a professional photoengraver, specializing in three colors. Both insisted on beautiful books, bindings and typography—necessarily expensive, though neither was in business for money. Emerson founded the Camera Club in London, the first important amateur club in England ; Stieglitz welded together two desultory amateur societies into what became the mighty Camera Club of New York. At this point, these two great masters begin to part. Emerson’s prepared Nature and Art never materialized; Stieglitz, having been an editor on the staff of The American Amateur Photographer, went on to edit four more magazines: Camera Notes, Camera Work, “291 ” and MSS. Emerson never ran a gallery; Stieglitz ran The Little Galleries of the PhotoSecession, which became the astounding “291,” and later The Intimate Gallery and An American Place. At the galleries, during the winter seasons, he was there, ill or well, from 10:00 to 5:00. When he could, he photographed New York City, the harbor, the streets, the rising skyscrapers, often in storm or night, often from his windows. During the summers, up at Lake George, he photographed the house, the lake, the barns, the trees— people in the water, on the porch, in a rowboat—until he was too weak and ill, at seventy-three, to set up camera any more.

In spite of the long silences, Emerson seems to have had a proprietary, even familiar feeling about Stieglitz, as if he were, photographically speaking, his son, or perhaps an erring nephew in need of a strong dose of the truth at certain times. It is doubtful if he ever realized how far his “son” had outrun his every dream.

The differences in temper and temperament between them widened as they grew older. Emerson, after his unnecessary selfcrucifixion on the cross of art—a man of high integrity and courage, he had to do it—could not, thereafter, ever chop and change; the Calvinists behind him forbade any backsliding. After his discovery of a new world and its beauties, his battles for it, his endurance of all the verbal sticks and stones which can do worse than break bones — a broken spirit and heart may never heal, but the breaking had been his own act—from then forward he pursued a steady course, no matter how ominous the sky, how dire the storms.

Not so Stieglitz. Impossible to defeat this man. Stieglitz too fed thousands on the loaves and fishes of his spirit; he too was hailed in triumph; he too had his crucifixions —which turned into transfigurations. He believed in life and art as its greatest and purest expression, and whether the expression was photography, or African sculpture, or children’s drawings or Picasso, or Brancusi, or Gertrude Stein, or Ernst Bloch in music, or the faithful service of Andrew, his matter and framer, it was no less life and art.

Stieglitz in his old age commented that his life had been a series of secessions. By that he did not mean the Civil War, the War of the Secession; he meant something much closer to a revolution of the spirit of the times. A brief, occasional sketch of these secessions may be helpful to those who do not know the life of Stieglitz, since they illumine the unknown later life of Emerson.

The first was not of his making. In 1890 Stieglitz was studying in Vienna with Josef Maria Eder, the photo-scientist, when his mother, heartbroken over the death of a daughter, begged his father to call Alfred, their first-born, home. Stieglitz did not want to go ; he loved his life in Europe, he had just won a scholarship and the future in photography looked bright. He went, in August, 1890.

Emerson, preparing for his year on the Broads, wrote him:

I congratulate you on the scholarship—Bravo! We are all winning around here and soon everybody will be a Naturalist. I hope to see you working with Beach on the American A P when you get back. . . .

I hope you will get a publisher in Germany. I am preparing the 3rd ed which will be published in the spring. I would rather you published a German translation from that as there are important alterations, not of principles but of matters which further confirm my teachings. . . .

And after that note, silence for twelve years. Why?

When Stieglitz got home, he found his parents insisting that he go into business, marry, and settle down. There was nothing he wanted to do less; he wanted to be free—free to wander and to photograph, experiment, perhaps run a magazine and assemble exhibitions of the most exciting and beautiful photographs. Nor, as he maintained all his life, did he feel man enough to assume the responsibility of a wife and family.

Then his father bought an interest in a company which was to be the first in America to develop three-color gravure. What better business for Alfred, with his fame as a photographer and his training under Vogel and Eder?

Was it at this point that he wrote Emerson that, being no longer in Germany, he could not easily find a German publisher, and that, with his present schedule, he could no longer take the time to do a translation? The truth was, of course, that he had lost interest in the idea. And Emerson, probably off on the Broads and wrestling with the problems that led to “The Death,” undoubtedly felt this and was a little hurt.

This is pure conjecture; Stieglitz may never have written at all. But he said he felt differently about Emerson after “The Death,” as if he had been false to his own ideals, in which Stieglitz still passionately believed. He himself, after Vogel and Eder, took H&D in stride and went on to push the medium beyond its then accepted limits—into night, rain, and storm.

Meanwhile, he became a professional photoengraver, making and printing the first three color gravures in the country—an invaluable experience.

In July, 1893, Emerson’s wish for him was fulfilled: his name appeared on the masthead of The American Amateur Photographer. All went quite well until Stieglitz devised a rejection slip worthy of Emerson: “Technically perfect; pictorially rotten!” This worried Beach a good deal; he felt he was losing subscribers. Stieglitz felt it was a good way to get rid of the dabblers and the fuddy-duddies who cluttered the American pictorial scene.

In 1895 he seceded voluntarily for the first time: he said he was “tired of doing business with a lawyer on one side and a policeman on the other,” and left the gravure company to his partners. The next secession was from The American Amateur Photographer. Beach published a copyrighted photograph without permission, was sued and forced to disclose his true circulation, which was a good deal smaller than he claimed for advertising purposes. Stieglitz resigned in disgust.

All this time he had been making photographs, winning medals (some one hundred and fifty in about a decade), writing articles and reviews. In 1894 he had been elected to the Linked Ring, then regarded as a great honor. Since, like Emerson, he never had to work for a living nor accept a job for pay, and now that he was free, he decided to do something about the desultory state of American amateur photography.

He welded together two clubs, one of which was thinking of becoming a bicycle club, into the Camera Club of New York. He refused the presidency but accepted the vice-presidency, saying he thought he could make the post more than a mere figurehead. Still, nothing seemed to happen creatively, so he asked the Club to let him take over the monthly bulletin they sent out free to each member; he had in mind a quarterly to be called Camera Notes. Each issue would comprise a thousand copies, and outsiders could subscribe for a dollar a year.

Camera Notes speedily became the most exquisite and exciting periodical of its time. Europeans began talking about it and subscribing; soon its first numbers at auction soared in value. It made the Club famous. And Stieglitz, traveling around on his frequent judgeships, began bringing back gifted unknowns who in turn brought others; he, for instance, found ClarenceH. White, of Ohio, and White foundEdward J. Steichen, of Milwaukee.

Soon, it seemed to the original New York members, more of the Club’s exhibition space and more of the pages of Camera Notes were being given to these outsiders than to themselves.

Their protests mounted until, in 1900, Stieglitz resigned as vice-president; in 1902 they fired him as editor of Camera Notes, which speedily collapsed.

Having recently been asked by the National Arts Club of New York to organize an exhibition of photographs, Stieglitz chose his favorites with no club to hold him back. He felt strongly that both the contents and the title of the show should constitute a declaration. Thinking of his friends, the painters in Munich and Vienna, who called themselves the Secession, he suddenly had title and theme—The Photo-Secession! Asked who belonged, he said, “Yours truly, for the moment. But there will be others.”

The show was an immense success. And Century magazine asked him to do some articles on photography.

How much of this did Emerson know? The main events, probably. If he did not personally subscribe to The American Amateur Photographer and Camera Notes, he could peruse them, whenever he went to London, at the RPS. But it was in the October 1902 number of the Century that he got a shock.

In his second article, “Modern Pictorial Photography,” Stieglitz began:

For some years there has been a distinct movement toward art in the photographic world. In England, the birthplace of pictorial photography, this movement took definite shape over nine years ago with the formation of the “Linked Ring,” an international body composed of some of the most advanced pictorial photographic workers of the period, and organized mainly for the purpose of holding an annual exhibition devoted exclusively to the encouragement and artistic advancement of photography. This exhibition, which was fashioned on the lines of the most advanced art salons of France, was an immediate success, and has now been repeated annually for nine years, exercising a marked influence on the pictorial photographic world. These exhibitions mark the beginning of modern pictorial photography. Exhibitions similar to those instituted by the Linked Ring were held in all the largest art centers of Europe, and eventually also in this country. America, until recently not even a factor in pictorial photographic matters, has during the last few years played a leading part in shaping and advancing the pictorial movement, shattering many photographic idols, and revolutionizing photographic ideas as far as its art ambitions were concerned. It battled vigorously for the establishment of newer and higher standards, and is at present doing everything possible still further to free the art from the trammels of conventionality, and to encourage greater individuality. . . .

He continues by telling of the acceptance of photography in various art salons, ending with the ridiculous tale of the Champde-Mars in Paris accepting ten of Steinchen’s photographs along with his drawings and paintings, and then, on learning they were photographs, refusing in horror to hang them. Stieglitz goes on to praise the expressive qualities of the manipulative processes, and lists the leading photographers of Austria, Germany, France. Then:

Great Britain, too, has her photographic celebrities, who have done their share in furthering the movement in pictorial photography by the individuality displayed in their work; the foremost are J. Craig Annan of Glasgow; A. Horsley Hinton, George Davison, Eustace Calland, and P. H. Emerson, of London.

Imagine Emerson by this time! Stieglitz must have been in great haste and at crisis in his own affairs to be so careless and thoughtless. And he did, at this time, disagree with Emerson, as the last paragraph proves:

It has been argued that the productions of the modern photographer are in the main not photography. While, strictly speaking, this may be true from the scientist’s point of view, it is a matter with which the artist does not concern himself, his aim being to produce with the means at hand that which seems to him beautiful. If the results obtained fulfil this requirement, he is satisfied, and it is to him of small consequence by what name those interested may see fit to label them. The Photo-Secessionists call them pictorial photographs.

Emerson’s expostulation is more than usually illegible; someone has interpolated between the lines a kind of translation. Stieglitz, knowing what an indomitable fighter he had roused against him, undoubtedly wanted to know what next.

Ailsa Lodge W. Christchurch, Hants. 1/10/02

Dear Mr. Steiglitz

I see an article of yours in this month’s Century in which you are good enough to remember my name. Knowing you or rather your career as I do I feel sure you are the last man to falsify history. You have been imposed upon as have a good many others by pushing and unprincipled charlatans. Of all the names you mention as having made modern photography the only one besides my own which has any claim is that of Mr. Davison, who was a follower of mine in company with Mr. Graham Balfour, Mr. Colls and others but who wandered afar [?] the battle and.... [Davison became an anarchist] and found his congenial home of art in commerce in the Kodak Co. As for the counter-jumper Hinton . . . he is a charlatan who has openly confessed to several of us that he made . . . so-called art-photographs for the f.s.d. he could get out of them.

Nearly everybody . . . long since has found him out and if I may be permitted to say so you are misrepresenting history and misleading people when you write as you do of these people. When I come to write the whole inner history of the whole business you will I am sure regret that you have allowed you self to be humbugged by charlatans.

I must ask you to consider this letter as private and only send it to you out of your young honesty of purpose and enthusiasm, which I for one consider wasted on a dead cause.

Faithfully yours

P. H. Emerson

A. Steiglitz Esq.

Stieglitz, when this had finally been deciphered, must have been aghast at his own thoughtlessness. How could he get so caught up in the whirlwind of his own recent affairs as to forget what Emerson had done for photography and, for that matter, himself? He must have rushed to get off a letter on the next boat. But in those days mail took two weeks to cross the Atlantic, so that a reply, even posthaste, could not be received by the sender under a month.

Emerson’s next letter, again from Christchurch, is dated 26/11/02.

Thanks for your letter. I felt sure you wished to give facts, but you see you have been away from the center of the storm.*

Davison up to a certain period (when he had learned my methods, which I have letters of his acknowledging) did help on the cause— then he was too vain and too ignorant to pursue the very legitimate means of experiment in pictorial—and he joined the charlatans and did more harm than good. Hinton came into the business a good deal later than Davison—had nothing to do with the development of Naturalistic Photography and struck [?] a meretricious, usually faked landscape which for a period here surely amazed the ignorant press man Gleason White—a little bookseller who came to his new home ( at Christchurch ) and who is a dabbler and scribbler introduced to the press of an artistic friend of mine who always smiled at his reputation when he set it. — But no serious artist ever considered being any maybe ... than the 1000 and 1 scribblers who lie and throw pens. Eustance Calland never did anything to merit his name being remembered and I say this to you although he came before Davison and who has always been honest—among the true aesthetes [?] of those who gave it up in disgust. He was Louis Stevenson’s cousin and a high classical scholar . . . and if I say so my pupil before Davison took up with Nat. Photoy. If you will permit [me] to say so I have always considered you as man and honest and you must of course follow your own impulses. I perhaps have been able to plumb the depths—or rather shallows—of Pictorial Photography sooner than others through having a lot of real big artists as friends and I assure you it is a dead cause. I cannot go into full details in a letter—but my last edition of Naturalistic Photography which I have not discarded ought to explain all to you if you are not impatient of carefully weighing the other side of the question.

The chief people are included in every [?] Pictorial Photography by the editor of the A P and as he confessed to us he did it for money you can see what his communications [?] are worth and Snowden Ward also as anyone can tell you does it for some trading purposes. ... I remain honest and unprejudiced ever. . . . The only use I can see in anything is many proofs [?] to guide the young professional so that he will not produce the frightful things of years ago—how few a man of brains like yourself—You will I feel one day agree with me that you have banked [?] your talents on a Strumpet)— i.e. pictorial photography.

*Obviously Emerson had so lost touch with America that he was unaware that the “storm” had moved from London to New York, and that Alfred Stieglitz was its “center.”

I would not take the trouble to tell anyone to escape that I know I personally have influenced it is a dead cause ( a lie a few now have found out for themselves) but when I feel I have influenced anybody I feel a sense of responsibility. I wasted some of the best years of my life and for me a lot of money on the Strumpet. . . . Had I been able to produce a book like my own Nat. Photoy. (last ed. ) I should have. ... in for it and been in a very different position than today. . . .

Kindly regard my letter as private and wishing you a speedy enlightenment so that no more years may be wasted.

Believe me—yours faithfully

P. H. Emerson

If you honor me with any more letters yourself, kindly address as above and not c/o the Royal Phot Soc—

Finally, the first number of Camera Work, dated January, 1903, but delayed by Stieglitz’s insistence on perfection, was ready. Crews of Photo-Secessionists had worked days and nights around the Stieglitz dining table, tipping in the superb gravures of Gertrude Käsebier’s portraits and Stieglitz’s “The Hand of Man” and the branch of baby birds, each subtly toned to be as close as possible to the original. The response to the announcements had been gratifying.

Stieglitz had sent a copy off to Emerson, together with a letter which may well have summarized what all photographers and photoengravers owe to him and how much Camera Work itself was due to his pioneering efforts. Beyond doubt, it also contained a plea for more legible handwriting.

Emerson’s reaction is curious. He does not note the Käsebiers nor “The Hand of Man,” he does not comment on the quarterly’s exquisite qualities—the soft gray cover, with Steichen’s design for the title in a paler gray, the delicate tissues protecting each gravure, the rich paper and distinctive typography. None of these could he have missed, after the books and portfolios he had himself designed and produced.

ll/IV/03

Dear Mr. Steiglitz

Thank you very much for your kind letter and No. 1 copy of your new venture. I must apologize to you for my infirmities—calligraphic—a friend of mine gets in a blacksmith to help him. Verb: sap.

But if I may be so bold what do you in the company of Hinton, Child Bayley, Demachy & Co. [He is pouncing on the Foreword, which lists their names among its supporters.] I always placed you higher far than these, and if the Strumpet is still a Circe toward [?] you why not publish some of your own beautiful work in a good style and leave these penny-a-liners and splodgers to their own devices. It is I hope not ungracious to look a gift-horse in its mouth—but how you give business to these pictorial photographers.

Davison as I tell you gets his living out of it and is a good business man. Hinton was a shop-walker, is what I call illiterate and uneducated (for the science of the A.P. is the work of T. Bolas) and the editorship of the A.P. is his living. If pictorial photography dies as it will—he will have to turn professional or go back to shop walking or such. Of late hear sounds of Journalism. Snowden Ward is a publisher and a pushing business man. . . .

[This is a letter of such illegibility that I am reduced to the following scattered phrases which may, however, give the general drift. N.N.]

. . . shallow people of no account with a handful of amateurs who take photos in their spare moments. I know of nobody except myself who can give up his trade or profession for it. ... You have Mrs. Cameron’s work—it is simply unshakeable. . . . Photography as an Art is a Strumpet and as a science it must. . . careful watching . . . one of the greatest German geologists . . . has had to give up its use in the science of geology, and take engravings. . . .

For certain trial purposes it is of course useful illustrations for catalogues etc., records . . . and I think you will before you die agree with these.

The rest of this letter seems to be lost. The next two letters, from 1904, appear to cast light on a mystery: Why did Stieglitz never publish Emerson’s prints and/or words in Camera Workl

Curmudgeons were nothing to Stieglitz, except possibly as entertainment. And as for the difficulty of making a new gravure from an old one, from an earlier stage of the process, especially if one’s standard is as close as possible to perfection—even that might not have stopped the skilled professional he was. It is possible that he did not know of Life and Landscape on the Norfolk Broads and its forty actual platinum prints, which he could easily have reproduced in all their luminous loveliness. And what an introduction six or eight of these might have been to a number of Camera Work! Each issue was numbered, I to XLIX-L, some double, some special, to make up for appearing very late (frequently the case with avant-garde publications). Each number was dedicated to a portfolio by one artist, one pnotograph to a spread, no words except the titles on the introductory page. A few others appeared further on, among the articles, by other photographers. Thus each was usually referred to as the Käsebier Number, or the Steichen Double Number, and so forth.

The first letter implies that Stieglitz had asked Alvin Langdon Coburn, a very young Bostonian with a private income who was already an inveterate globe-trotter, to find out what Emersons were available.

Foxwold Southborne-on-Sea W. Christchurch 21/l[?]/04

Dear Mr. Steiglitz

I trust you are ok as of this.

I write to tell you that I replied to Mr. Cockburn’s card at the Carlton very much in haste. I misread his name for Cohen and so addressed it to Mr. Cohen with his initial—but will find it in the letter office. I just want to man the rifles to show him I was not impolite enough to take no notice of his card.

I also note in your letter Al Cockburn brought to the new gallery you ask if I can put you in the way of getting one of my portfolios. I regret I cannot.

I have only one and have no idea where one could be bought, for they cost money. The only illustrated books of mine which are not quite sold out are:

Life and Landscape on the Norfolk Broads S. Low & Co. publisher. £ 6.6.0. A few left.

Wild Life on a Tidal Water. Edition de Luxe. D. Nutt—publisher. £ 3.3.0 A few left.

On English Lagoons Edition de Luxe. D. Nutt—publisher. £1.1.0 —and the rest are pictures [?] etc.

Excuse this hurried note—but I have a pile of correspondence on my schedule.

Yours ever P. H. Emerson

The next is a fragment, the front page or pages having apparently been lost. It cannot, however, have been written much before the middle of 1904, since it reviews the first six numbers of Camera Work.

. . . wandered from the true and narrow way that you can think anything in the publication worth issuing ... in the eyes of cognoscenti to raise photography.

No. 1 [Portraits by Gertrude Käsebier; “The Hand of Man,” the great locomotive puffing on its shining tracks, by Stieglitz] Too low in tone with a meretricious trickle [?] of light.

No. 2 [Portraits by Steichen] Flat, banal, and terribly crude and amateurish in composition.

No. 3 [Clarence White] Commonplace, false in values and childish in composition.

No. 4 [Cathedrals by Frederick Evans, who confessed his “pet heresy” was pure photography; “The Flatiron Building” by Stieglitz] Head too big, hands ditto. [Name undecipherable] is being damn bad — a rotter. *

No. 5 [Robert Demachy] Cui bono?

No. 6 [Alvin Langdon Coburn] Best destroyed at once.

* This is incomprehensible. Who can Emerson have mixed Evans with? Steichen? But the undecipherable name looks more like “Young Annan,” who doesn’t appear for a year or two and of whom it would not be even acceptably true anyway; most of his work is landscape.

The “art” seems to lie in the paper used and reminds me of weak art students who cannot draw well in chalk on white paper and use white chalk on dark paper and so get a meretricious and facile “artisticness” which the learned advise the real student to avoid. I cannot truly accept your very kind offer to appear in that crowd in any capacity for as far as I can see excepting yourself they are a lot of incompetent poseurs and as for raising the Strumpet—why it is merely adding more rouge and powder to an aging and decaying Strumpet. Hence these tears.

Yours as ever P. H. Emerson

This was enough for a perpetual silence, but in 1904 the periodic trip the Stieglitzes made to Europe included, for the first and only time, England. In a very amusing series of sketches called Time Exposures by Searchlight (New York, 1926), Stieglitz, listed as “The Prophet,” is reported as going to England especially to tell George Bernard Shaw what he thought of him. On the Channel, he gets so sore a throat he loses his voice. Since he can not possibly cope with Shaw without a voice, when he gets to London he cancels his luncheon date with Shaw by telegram and leaves England immediately.

What Stieglitz told me does not necessarily invalidate this tale. He had written Emerson he wanted to see him, specifying hotel and date. He said he wanted to talk to Emerson, not with him. But Stieglitz, like many whose intense energy is spiritual and emotional rather than physical, was actually frail and often ill. He said that when he arrived in London he had so high a fever he was forbidden to talk. Through the fever he dimly perceived a man come in, look down at him for a moment, then leave without a word. They told him afterwards the man was Emerson.

Many years later Stieglitz asked Emerson if Coburn brought him, and Emerson answered: “No. You asked me to come see you and I did. Coburn was already there.” Which seems proof enough. “So,” said Stieglitz to me, many years later, “you see we almost met!”

It is as fascinating as it is futile to speculate what might have happened if Stieglitz had had his voice. Shaw, I think, would have been immensely amused and written so brilliant a comment that Stieglitz could not have resisted putting it into Camera Work. With Emerson, my bet is that it would have been a draw, with Emerson composing a magnificent epithet— printable?—and stalking stiffly out. With the Stieglitz of, say, 1914 or 1924, it is doubtful if even Shaw would have had a chance, barring a witty riposte in a note. As for Emerson, would it have been too late for him to understand what Stieglitz was about? Probably he was too hard-set in his thought—but if the two had really ever met, in the true communion of brain and heart, the history of art, including photography, might be different.

In 1905, Steichen, who had come back to New York for a while, suggested that the apartment across the landing from his own on lower Fifth Avenue, near Madison Square, might make a nice little gallery for the Photo-Secession. After all, only a few things could be shown in Camera Work in one issue; the Secession did need walls, and a place to meet and have visitors. Whether it occurred to either of them that this would also be a forum for Stieglitz is unknown. Stieglitz signed the modest lease, and Steichen designed the simple, subtle, but for those days startling decor of the two little rooms, found the huge brass bowl, often filled by autumn leaves or spring branches, for the center table, limited hanging to the eye level and protected prints and books under a bookcase with pleated skirts below. And so began The Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession. Steichen, the painter, specified from the first that media other than photography should be shown on its walls.

Stieglitz himself did not begin to glimpse the Strumpet until a year or two later. His colleagues were twitting him for being so pure and old-fashioned; Steichen, world-famous now for his huge two-color gums, advised him not to send to shows any more unless he did a little revolutionizing. Stieglitz merely laughed. He knew what they all thought. He still believed in each realizing his own mode of expression. He had sometimes yielded to a delicate soft focus, often the perfect expression of a subject, such as his little daughter touching a blossom, or a lovely passing lady, or a spring shower on a young tree in half leaf, with a street sweeper below and the dim towers of Manhattan behind. Or the prizewinning “The Street, Winter” —the soft snow falling on the hansom cabs, the brownstones, the man walking in a long cape. Some twenty years later, a critic who doubted there was a hansom cab to be found in New York City remarked that the picture did not look dated.

But around 1906 Stieglitz began to be bored and oppressed by all the preening little personalities, with their jealousies and squabbles. Who was seeking truth or new beauty? Or life? Or anything but his or her own praise?

In January, 1907, he suddenly surprised everybody by devoting the Little Galleries to an exhibition of watercolors by Pamela Coleman Smith, an American illustrator living in England. Expressionistic, wild in color and image, her work must have been a shock to the photographers. Steichen, who was back in France, cabled: WANT RODIN DRAWINGS? Stieglitz cabled back: YES.

1907 was a portentous year. On the steamer to Europe, Stieglitz found he could no longer stand the overbearing people and strident voices of first class—which his wife insisted on—and walked forward. There, down below, were the people in steerage: the people, returning to Europe, for whom the present America had not been Paradise. Stieglitz rushed back for his Graflex, breathless. (He has often told this story.) Yes, nobody crucial to the composition had moved—the man in the straw hat, the man in suspenders. He developed this single negative with prayer in Paris. He was laughed at—all that complexity of figures split by huge diagonals. But Picasso, who that same year did his strange split-vision “Demoiselles d’Avignon, said when he saw it, “This man is working in the same direction I am.”

Then, in 1909, Stieglitz and Steichen were wandering through a large photograph exhibition in Dresden. Steichen, who had been the greatest show-off of them all, but who had both power and perception, said to Stieglitz, “Yours and Hill’s are the only ones that stand up.” Then he himself seceded from photography—the Strumpet anyway—and went back to painting and plant-breeding. And began sending to Stieglitz small shows by friends of his whose names were then unknown in America and even sometimes in Paris: Picasso, Braque, Matisse; some, like Cezanne, who were dead but recently recognized as geniuses; a couple of young American students named John Marin and Marsden Hartley. Fewer and fewer photographers were shown, and some years, none at all.

In 1910 the Photo-Secession organized a huge international exhibition of pictorial photography at The Albright Art Gallery in Buffalo. It was actually a series of one-man shows grouped by nationality. Velariums were hung, where needed, from the high ceilings to bring down their height and diffuse the skylights. Blue gauze was laid over the burlap walls to give them delicacy and a softer color. A team of four—Steiglitz, Paul Haviland, Clarence White and a new member, Max Weber—organized and hung this show. Installation, already become a fine and subtle art under Stieglitz and Steichen, rose to a new height with the help of the young painter Max Weber.

The Strumpet in her Pictorial guise had a splendid funeral. Everyone knew this was the death of the Photo-Secession, and many sincerely mourned its fighting spirit; it had been heroic, a magnificent gesture.

But the fighting spirit of art was flaming higher and more brilliantly than ever. And the Little Galleries became the famous “291,” after its address on Fifth Avenue.

Stieglitz did little photography if any in these years; he had to save his energy for converting visitors to seeing the vitality and beauty of early twentieth-century art and for presenting it with equal force in Camera Work.

In 1913 came the great, shocking International Exhibition of Modern Art, the “Amory show”; Stieglitz and “291” had sparked it. As honorary vice-chairman, he was exultant, vigorous and vociferous. At “291” he showed, for the first and only time, a one-man retrospective of his own work: critics found the counterfoil fascinating. And he must have been amused to open the New York Evening Sun and find the most controversial painting in the show, Marcel Duchamp’s “Nude Descending the Stairs,” inspired by photographic studies of motion, caricatured as a subway rush: “The Rude Descending the Stairs.”

Emerson did write Stieglitz one letter in 1914—just before World War I:

Foxwold [ ? ] Southbourne Bournemouth 31/V/14

Dear Mr. Steiglitz

Bedding gave me your address and I wonder if you can tell me anything about the Verito lens of the Wollensak Optical Co. Is it a semi-achromatic of the Smith type or one with primitive [?] spherical aberration or what. The Smith lens I do not regard with favor—Dallmeyer made me a lens like that 20 years ago and I rejected it—it gives a pin-holy effect and pin-hole effect is not the texture one requires at all.

How is Pictorial Photography in the States—it is practically dead over here except for some misguided and superficial people like Demachy and Co—they are doing bungling Photo-oleographs that are false in tonality and crude enough to delight a child.

I saw Coburn some time back—he is a sort of photo-journalist and is issuing topographical books on high [?] New York* etc. —he seems very enthusiastic.

I hear you do no more photography.

With kind regards F aithfully yrs P. H. Emerson

If Stieglitz bothered to answer this note, he probably told Emerson that yes, the Verito was not unlike the Smith; that many people liked it, though he himself neither liked the results nor had personal experience with it. And yes, Pictorial Photography in the States was dead if not worse.

Also that he hadn’t dusted off his camera lately.

Silence for another ten years.

Perhaps this is the place to sum up what happened to the lesser Pictorialists in the States. The strong, who had never really needed the favors of the Strumpet anyway, eventually gathered force and momentum to become the Purists, of whom more soon.

The weak, lacking their great leaders, forlornly huddled together and formed the Pictorial Photographers of America. They elected Clarence White their president, and when he died, in Mexico City in 1925, the last of their former standards died with him. They sank into unbelievable quagmires—trash worse than the Robinson period: babies, kittens and puppies of insufferable cuteness; bosoms brimming over gypsy costumes; the gray bearded old man with Bible or pipe, the old lady knitting. The greasy nude, often with Clarence White’s celebrated bubble, not without pornographic overtones. The absolute nadir was reached by one William Mortensen; one title and description will suffice: “Preparation for the Sabbat”—an already gleaming nude ramping on her broomstick in the firelight, while a shadowy old crone applies the last grease and gives the last unholy instructions.

*New York, 1910. Introduction by H. G. Wells.

That August of 1914, the Great War began crashing over the world. Emerson’s elder son, Leonard, was probably among the first to enlist, and probably at once commissioned an officer. The younger son, Ralf, was only sixteen but may have edged in later toward the end; perhaps this was the beginning of his military career in the Royal Engineers. During World War Two he was promoted to colonel and knighted for his services and his courage. How proud Emerson would have been! He must have fumed that, in 1914, at fifty-eight, he was himself too old to fight for England.

Stieglitz, on the other hand, could never quite believe that the good and gentle Germans he had loved and lived with in the ’80s were capable of the atrocities reported of them—the massacre march through Belgium, the burning of Louvain, the shooting of hostages. Most of it must be propaganda, mere hysteria. In the first years of the war, this didn’t matter; America was determined to let Europe fight her own wars.

The shows at “291” had never been better: African Art, Children’s Art, Brancusi, Nadelman, and in photography Paul Strand (“the man who has done something from within . . . the work is brutally direct—the expression of today”). And the reaction to Stieglitz’s question “What is ‘291’? I know it is not /” evoked so wide and multi-toned a response that he devoted to these letters the single issue of Camera Work that contains no illustrations.

If Emerson, as he later states, was appalled by the delicately colored reproductions of the strong, free Rodin drawings (what ugly women in what awkward motions! ), the Picasso charcoal all split into curves and angles, and the repetitious writing of Gertrude Stein, what must he have thought of any of the twelve issues of the magazine “291 ’’which may have survived the wolf packs of submarines to reach London? Satire, caricature, experimental typography. The first issue contained an “Ideogramme,” a poem by Apollinaire in picture form. The first important proto-Dada eruption. Picabia’s cover, with a lens pointed toward the word “ideal” detached from its Kodak, and beside it “Ici, c’est ici Stieglitz foi et amour.” The bold caricatures of Marius De Zayas; Picabia’s amusing and satiric machine drawings. Almost the whole roster of avant-garde artists and poets in both Europe and America. Emerson must have torn at what was left of his hair: was Stieglitz crazy or had he just gotten in with “a rotten crowd?” Shades of his good friends Goodall and Thomas!

But then the attitudes of Americans began to change. The doctrine of Schrecklichkeit (“frightfulness”) came home to them with the sinking of the Lusitania. Only the intelligence officers on both sides knew that, apart from passengers, her cargo was ammunition for the Allies. Britain, “perfidious Albion,” calculating that drowning a hundred or more Americans, among the horrendous list of victims, would bring the United States into the war, where its tremendous forces were badly needed, merely withdrew an expected protective warship and the German commander on the submarine was able to carry out his orders.

“The war to end wars” was on.

Friends began dropping away; “291” was dying, and so was Camera Work. The defection that hurt the worst was undubitably Steichen’s. After all, he had been born in Luxembourg, one of the first little countries annihilated. A lieutenant, he soon became chief of aerial photography for the U.S. A. He was desperately in need of film and other necessities, and glad he knew his way about European photography. But when Stieglitz offered to get the desultory Eastman Kodak Company going on its promised deliveries, Steichen ignored him.

“291” and Camera Work both died in 1917. As Stieglitz said, they began clean and they died clean. Photography died with Paul Strand, in the last double number of Camera Work; painting, with Georgia O’Keeffe—that last show on the walls of what she says was the most beautiful place she ever saw.

In 1915, Anita Politzer, a girl Stieglitz had seen “100 percent alive” in front of the Picassos, brought him a roll of charcoal drawings, telling him she had been enjoined to show them to nobody but felt she must show them to Stieglitz. He was amazed—“At last, a woman on paper!”—and insisted on keeping them, saying he would look at them several times a day for possibly months. They were not signed ; all he knew was that a woman of genius had made them.

He hung them, completely convinced. Suddenly a thin girl in plain black with a white collar confronted him. “Who gave you permission to hang these drawings?” “Nobody. Myself. They asked to be hung.” “Well, I made them. I am Georgia O’Keeffe. Take them down.” Stieglitz persuaded her she had no more right to keep these things from the world than a child had she borne it.

Did he see then in this spare, plainly dressed spinster, a Texas schoolteacher, her extraordinary beauty?

At last the senseless war was over. The stench of the millions too blown apart to be buried was dying from the battlefields; towns and monuments were being rebuilt.

Free now of gallery and magazines, alone since he and his wife had separated, Stieglitz could at last devote his full energies once more to photography. He had picked up his cameras occasionally during the last few years, photographing the clear, exquisite installations and also making a series from the windows of “291”—a little tree covered with fresh snow, dim lighted windows on a misty night. He had also begun to photograph O’Keeffe when she came to New York; in 1918 she came determined to make her living as a painter somehow. The little money she had saved soon ran out; she would have to go back to teaching. Stieglitz’s own income had dwindled seriously, but he offered her enough to live on for a year and just paint.

They shared a studio together. Suddenly, without intent on either side, as Stieglitz said, “It happened.” Exalted, deeply in love, both transcended any work they had done before. Stieglitz made a hundred or more photographs of O’Keeffe—everything about her: feet, hands, breasts, torso, ears, clothes, and most of all moods and emotions. He called this series “The Portrait of a Relationship.” He began to photograph a number of his friends with the same series idea of conveying a whole personality—not just one face, one mood, one setting, but as living beings, moving, sensing, changing.

Young photographers, coming back from the nightmare battlefields, their roots torn out, or equally uprooted by the stupidities behind the lines, found “the old man” (he was in his fifties) had performed miracles. There had never been photographs like these —so simple, so penetrating, so profound. No tricks, no personal theater, not even a signature. Clear and yet abstract in plane and form.

Various photographers reacted in astounded ways. Steichen, now in a colonel’s uniform, found the amazing experience of both O’Keeffe’s paintings and Stieglitz’s photography so overwhelming that he was nearly in tears and then, deciding he was tired of being poor, went into fashion, portraits of the famous, and advertising —in all of which fields he raised both the standards and the prices considerably. Edward Weston was already making the painful change from prizewinner of the salons to the great artist he became; he decided to go to Mexico and found his own new formal approach, both realistic and abstract, an inspiration to the artists there—Rivera, Orozco, Siqueiros.

Paul Strand, so close he felt like a son, was perhaps the hardest hit. During the war he had been an x-ray technician and then made medical movies. But back in the early ’20s he could not at first see past Stieglitz and could only imitate him. The imitation extended even to photographs, Paul trying to photograph his wife Rebecca as if she were Georgia. Stieglitz tried to prove to Paul that in Becky, daughter of vaudevillians, he had a much more pliant and vital model than the then rather fragile O’Keeffe. He made a series of nudes of Becky in the cold, sparkling water of Lake George; O’Keeffe could not at that time have endured such a trial. And why not find his own subject matter instead of the old barns and trees Stieglitz had been working with lately? Strand took his advice and began working with machines, such as his beautiful Akeley movie camera and lathes, and what was happening to the New York farm country as suburbia destroyed it.

In 1921 Mitchell Kennedy, who headed the Anderson Galleries, persuaded Stieglitz to give a one-man retrospective in two huge rooms. One hundred forty-five prints in platinum and palladium, less than a score from his early familiar work, 128 never shown publicly before. Sensation. “People came again and again. At times hundreds crowded the rooms. All seemed deeply moved. There was the silence of a church.”

Emerson began to hear about this from travelers recently in New York. Perhaps he also read in the Photo Miniature, July, 1921, what the editor, John Tennant, thought of that show; after summarizing Stieglitz’s career and his “impenetrable silence and obscurity” since “291,” and the question Where is Stieglitz?:

At once his answer and the challenge; the apocalypse of a personality unique in photographic annals this exhibition at the Anderson Galleries aroused more comment than any similar event since photography began, and deservedly, in that it was an exhibition of photography such as the world had never seen before. ... A revelation of the ultimate achievement of photography, controlled by the eye and hand of genius and utterly devoid of trick, device, or subterfuge! . . . Never was there such a hubbub about a one-man show.

What sort of photographs were these prints, which caused so much commotion? Just plain, straightforward photographs. But such photographs! Different from the photographs usually seen at the exhibitions? Yes. How different? There’s the rub. If you could see them for yourself, you would at once appreciate their difference. ... In the Stieglitz prints you have the subject itself, in its own substance or personality, as revealed by the natural play of light and shade about it, without disguise or attempt at interpretation, simply set forth with perfect technique. . . . They offered no hint of the photographer or his mannerisms, showed no effort at interpretation or artificiality of effect; there were no tricks of lens or lighting. I cannot describe them better or more completely than as plain, straight forward photographs... plus the nature, substance or personality of the subject, the vital interest, truth and life of the subject, resulting from an absolute mastery of the mechanics and technique of the photographic process. . . .

. . . They made me want to forget all the photographs I had seen before, and I have been impatient in the face of all the photographs I have seen since, so perfect were these prints in their technique, so satisfying in those subtle qualities which constitute what we commonly call “works of art.”

Accused of hypnotizing his remarkable sitters, Stieglitz turned his Graflex to the skies. “Clouds ... I always watched clouds. Studied them. . . . I wanted to photograph clouds to find out what I had learned in forty years about photography. Through clouds to put down my philosophy of life. . . . Clouds were there for everyone—no tax on them yet—free.”

He also discovered that poignant images evoking intense response from others—equivalents, as he called them, the clouds — ecstatic, emotional, meditative—and also simple, profound details, such as the rain-dripping apples before the gable at Lake George, photographed while his mother was dying, a rainbow plunging into the woods, the dying chestnuts crying in protest, the poplars accepting with grace their usual silver death, the old gelding in harness, which he called “Spiritual America” (workhorses in Europe were not gelded), the old dark barns at Lake George with melting snow on them—they were images of sorrow, mostly, but though few bore titles, people found in them something they felt which had never been expressed before.

As for reproducing his recent photographs, Stieglitz said NO to all comers. There had been such enormous changes in the photoengraving world that he felt he would have to get back into the works himself to find out how these things should be reproduced. Nothing quite like them had ever been done before, much less reproduced. They were contact prints from the 8 x 10 or the 4x5 Graflex, moderately sharp; they were at one and the same time real, abstract and mystic. Stieglitz had grown tired, during the Photo-Secession, of sending out beautiful things and getting them back, however be-medaled, damaged—frames nicked, glass broken, prints scarred, mats dirty—and no longer sent things on tour. Rarely could even nearby museums persuade him to lend anything in his care or collection—painting, watercolor, sculpture — and still more rarely, his own photographs. He had arrived, as early as 1903, at the conclusion that, no matter how many prints you made from a great negative, or how you toned them or accented one center of interest or another, there was always one finest print, and that was worth a thousand dollars. But not everyone who offered a thousand dollars—always as a donation to An Intimate Gallery or An American Place, never to Alfred Stieglitz —was allowed to have one. The same was true of Marin watercolors, O’Keeffe paintings, Lachaise sculptures and Dove metal paintings. “How much are you willing to give the artist?” was his invariable question to would-be collectors. But money could not buy art, nor could prestige. He would not let just anyone with money have these beautiful things; he had to be assured the possessor would love and understand them. And Stieglitz was by no means alone in his conviction that where photographs were concerned, museum people simply stepped on them or kicked them aside during installation. As for the postal services, we were all convinced the mail sorters played football with anything marked PHOTOGRAPHS-DO NOT BEND.

Praise for Stieglitz, for his photographs, his galleries and magazines, was coming from all sides, though no one who had not been in New York recently had seen the photographs.

In 1924 The Royal Photographic Society presented the Progress Medal to Stieglitz “for services rendered in the founding and fostering of pictorial photography in America, and particularly for his initiation and publishing of ‘Camera Work,’ the most artistic record of photography ever attempted.”

This undoubtedly spurred Emerson to undertake his longpromised “inner-history” of artistic photography; if he didn’t do it, no one, he felt, would ever know the truth.

5 Lascelles Mansions Eastbourne Feb 14 1924

Dear Mr. Steiglitz

Owing to the stupid and mendacious statements of the ill-informed I am writing a true history of the development of artistic photography.

I wrote to you some weeks ago to your address as given in the RPS list of members —i.e. Madison Avenue —and the letter was returned—marked “Return” [?] which I take is equivalent to “Unknown.” Then I wrote to Mr. Child Bayley who is a great admirer of yours and sent him the returned envelope and asked him if he could give me your current address, and he has given me the one on the cover which I hope will reach you.

What I needed to ask you is to let me see a half-dozen of your best prints of your photos done during the last five years. I know they are something especial but would be very much obliged if you could let me see them. I will return the stuff [?] and send them to Mr. Child Bayley. If you care to pen me a few brief biographical notes of your photographic work then I shall be obliged. I am most anxious to be fair to everyone whilst I agree that. . . but I took it you were led away by “gum” and “oil” for no one with real artistic feeling could be [taken] in by “pseudo-artists” like Demachy, Puyo, Coburn and co who could be led away by the rubbish. [?]

I am glad you got the progress medal though the ruling body of the RPS is so . . .to the progress medal that it is a dubious honour these days —but your genuine enthusiasm and work in the Camera publications deserved some mark —and perhaps your recent photographs which I am anxious to see.

Y ours very truly

P. H. Emerson

Stieglitz hesitated over this letter quite a while. The history of photography as an art (note difference in terms) did need to be written, but—by the opinionated bulldog Emerson? He was not going to send him any of his new work—What? Trust those prints to a steamboat handling?—though a crossing now took only one week. And he was certain Emerson, who had not even understood Camera Work nor kept in contact with twentieth-century art, would never understand them. Finally he wrote a letter explaining his present viewpoint, which obviously asked if Emerson thought he could really write such a history. Apparently he also included some comments by Herbert J. Seligmann, a friend and frequent visitor.

March 25 1924

I’m glad to get a reply from you at last. I don’t anticipate any difficulty in writing a real history. I have served my apprentice days in writing history for three solid years. I am writing history based on documentary evidence—and I flatter myself I know what art is and have had my opinions confirmed by the . . . artists with whom I have been brought in contact—to name two Whistler and J. Havard Thomas the sculptor an . . . old friend of mine, and the finest basrelief sculptor England has ever had. Then I have studied psychology— scientifically—I am a productive photographer. . . . “and we are the new men.” I develop all my own plates including the 24 x 22 before photography becomes fool-proof. . . .

I am not doing the scientific end—Eder did that and if he had not done it I should not be competent to do it.

I had a nice letter from Mr. Seligmann. I replied. . . . [This is a long and difficult letter of which I can decipher only an occasional phrase or sentence. N.N.]

The box of prints [?] and your letter has not arrived. I hope it will reach me by the next mail.

I of course can say nothing about your letter and photos until I see them —but somehow I think you are wandering far from the track in your thoughts. Why be so sensitive about not having any “ism” and objecting to Pictorial Photography. . . .

I think you are messing things up in the letters you sent about your photos. . . .

I object [to] your words straight photography . . . competent photographers can now be “straight” photographers. . . .

As for the museums buying your pictures ... I attach no importance to that. . . . many years ago some museums here and bigger ones [than the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston?] have shown examples of my work. Museum people are mere collectors. . . .

. . . puny literacy now in art photography. Coburn too. . . . empty and puff about his mediocre work . . . because Shaw and Wells wrote introductions to his books of prints. . . .

A painting is the result of the work of the brain and the hand — a photograph is the result of the brain and a mechanical apparatus —you can’t get away from that—no one can. . . .

Coburn . . . has not an original idea in his head and is no artist at all—he has no art.... I spent an afternoon with him here. He couldn’t see a picture in Nature! . . .

I have been very frank and hope you will understand. But I need to see your work. I hope you will be courteous enough to let me see it. . . .

How much of this letter Stieglitz could decipher is unknown. In any case, he sent Emerson a number of gravures, Paul Strand’s portrait of himself—in which he looks incredibly hoary, older than God—and quite a batch of clippings about his latest work.

April 6, 1924

Just a line to acknowledge your courtesy and kindness in sending me the New York Harbour and other publications which arrived safely. I am very interested in your portraits?] — but have been too busy to study any of the literature. I guess this is called literature and it fills me with amazement! Some of the writers cannot write clearly and there is a horrible pretension and affectation which is really laughable. America must be in a bad way to tolerate such piffle. I am no longer surprised at Pennell’s condemnation. . . .

In my humble opinion there is too much scribbling on “Art” and Photography. . . .

I hope to receive reproductions or copies of some of your “cloud songs”—

In great haste

Yours faithfully P. H. Emerson

Is Mr. Seligman your brother-in-law?

One can hardly fail to sympathize with Emerson. He does not say he has seen the gravures before ( in Camera Work ) and that the New York Harbor scenes are not too different from his own East Anglian; it is of course possible that he did not sense the much greater emotional impact and symbolism. But all those clippings! And yet, with them, none of those reputedly wonderful works which had elicited so much almost inarticulate praise.

Perhaps the most amusing of all these letters was written on April 30, 1924. And it may interest and entertain readers that Stieglitz’s own opinion of a few of those mentioned was not too dissimilar to Emerson’s.

Private

5 Lascelles Mansions Eastbourne Sussex April 30, 1924

Dear Steiglitz

Yes I heard you were top-notch at billiards—well you won’t allow it I know but our skill in billiards proved we had to my mind much more “art” than art photography because we could not show what was in us with the machine we could cry [sic] show up for a limit.

Paul Strand is an ignorant and pretentious duffer—he can neither write nor take a fine photograph judging from his portrait of you which is all wrong and proves he does not know the elements. It is dishonest in him to write as he does.

I think your friends would help your work along much more if they did not make comparisons and say it is far ahead of anything done —on which point I am agnostic until the spirit moves you to let me see 12 of your best things.

Mr. Seligmann has told me is no relation—you will allow a relative is bound to be inclined to favor his relatives —it is in human nature but now I know is his own spontaneous opinion. Bedding Chuff ran my work historically which he was competent to do —he said and many other papers . . . that I was founder of modern Pictorial Photography and this can be legally proved and I am providing the historical data to prove it. Then I showed Beddy letters artists had written me and he often met F. Sandys who is a great admirer of my work and one of the best English artists. Beddy is very modest and knows he does not know art —but when a new so-called artist cropped up in photography he always consulted artists —so in his opinion you really get a sort of composite of several artists. . . . Hence his condemnation of gum and oil.

I hope when you do decipher the rest of my letter you will find my sketch is not so far off.

Yes Coburn is a superficial, designing, unscrupulous little “bounder.” I don’t believe he could write that Ruskin cum Watts article on Beauty himself. He is as vain as a peacock with two tails—both which he has probably stolen.

Just a rotten little opportunist —he guns at what he has a poor hand.

The fuzzy types the Naturalistic work which he could never do for he could not see a picture in nature. He got the better scrawlers to write introductions to his books, and neither Shaw nor Wells know anything about art that I know from the artists who know them.

You see the present nincompoops who run the RPS want to make out I did as little as possible because I am an American and that’s all—but there are honest Englishmen who won’t allow it—Why shouldn’t anyone do photographs according to some art theory—in fact anyone does who does any artistic work, whether conscious or unconscious. I pay no attention to Rosenfeld —I could cut him to bone and ribbons—he does not understand at all and his style makes my head ache —he can’t write clear English—Seligmann can. . . .

Well send us along the dozen or baker’s dozen if you will and let me a fair look at your best work. If the work be as it will while here [it will be] no matter what anyone says. If it be not here [it will not] no matter how highly boosted. I think you will agree with this.

Look how photographers recorded Mrs. Cameron’s work but it came into its own all O.K. One photo society solemnly sat down and passed a resolution condemning it and it is entered in the minutes ( ! ) H. P. Robinson [intriguing?] and poking [her? them?] in the back and a lot of this —see Mrs. Cameron’s Annals of My Glasshouse.

With kindest regards Yrs faithfully

P. H Emerson

Then futilely:

May 7, 1924

I have had many very beautiful sets of photos sent to me and so kind are people that I am going to give three medals ( 2 silver and one bronze) for the three best prints sent in. The medals were those of me done by the late J. Havard Thomas, the best bas-relief sculptor England has ever had. . . . It is a work of art by a great artist and will someday be worth money.

I hope this may be an added inducement for you to send me twelve of your best photos—portraits and songs and nudes but especially I want to see . . . songs and the city and nudes and landscapes.

I will select three for the competition . . . and return you the rest in a week. . . the three I show to all my committee of artists for their opinions before I make the award.

You did show Strand didn’t you—and you might tell him of this letter ... to have sent me a dozen prints of his I shall be glad.

Why worry so about “aim” and “theory” . . . these neither are of any importance—all that counts is the photographs —by them alone will the future judge you. . .

I shall not print the names of [unaccepted?] competitors for the medals. . . . There will be no comparative criticism—either a man has art or has not.

I don’t see that it matters a halfpenny of gin whether you sign photos or not—some artists do. ... I happen to do it.

Dangling a medal (of himself) before Stieglitz, who, after winning 150 or so of the things, waged a campaign against awarding them—Emerson, of all people, who, after winning what he considered an inordinate number himself, withdrew his prints from competition! What psychology Emerson may have studied certainly didn’t include a key to Stieglitz ; in nearly a year of letters he tried every tactic he knew, including insult, and got nowhere.

And yet it could have been so simple, if he had the cash and health, to go to New York, see the wonderful things and talk to Stieglitz. They could have worked out together the means of reproduction— and many other tangled matters.

Plaintively:

5 Lascelles Mansion Eastbourne Sussex May 30, 1924

Dear Steiglitz

The weeks roll on and I am receiving parcels of prints from all parts of the world and [from?] you I do not even get a reply to my questions. Are you or are you not going to send me some prints — (portraits, Sky songs, and landscapes including the old barn with melting snow. ) If not please tell me and then I shall know where I am.

I had a parcel from Davison yesterday.

Faithfully P. H. Emerson

Be a sport and give us a chance!

Sheltered virtues have no merit.

Then he heard Stieglitz was ill and wrote, on June 6, 1924 :

I am so sorry you have been ill. I think you will find Lake George much better for your health than New York.

Please re-assure yourself that I have no feeling at all about not being included in Camera Work. You did ask me to write — this is quite true—and I gave you the real reasons why I did not want to. Hinton and Demachy did more harm to artistic photography than any two names I could give. Hinton confessed to me he took to it because he could never see a picture in nature. He began a Naturalistic and produced a lot of fresh stuff for that very reason. He thought [?] of possibly 15 of them and sent them to me for my opinion and I told him they were not worth keeping let alone publishing. He reproduced one the paper Photographic Art Journal—which see — a “frothy” thing—then he took to that terrible. ... a drunkard in ten days and died of delirium tremens. I guess Demachy is the same as far as inability to see pictures in nature and no one can be an artist without that. You will I think agree with that. . . . There is far too much rotten stuff written about it. That you should take Shaw’s opinion on photography amazes me—I would as soon take the man in the street—any man. . . . Shaw is a Irishman and like many of them hates England. Wells is an upstart and easily oversold [?] in every way.

“Gum” and “oil” are neither photography. They are bastard processes using photography and no photographer with artistic feeling would ever have touched either. Coburn tried gum and his “gums” are as feeble as anything else. I spotted his deceit at the very start—he . . . down to me on the pretext of taking my portrait and writing an article on my work for Platinotype — of course the article never appeared. I find him a wishywashy conceited vain and mediocre person—no delight in probing the characters of nearly. . . An insufferable little bounder. . . .

I was surprised to see you mention Robinson in your last—Surely you do not regret having not included him in Camera Work?

I have not seen Camera Work yet [Emerson is under the delusion that it was resuming publication, confusing it with MSS, the avantgarde little magazine Stieglitz ran in 1922-23.] —but from what I hear from competent critics—it is most incomplete as a recovery and you haven’t. . . . pushing a lot of feeble stuff of Caffin, Shaw and others.

I just have to combat that view of you alone—words being interrelated. I hold this to be a policy. A single work of art stands or falls upon its own intrinsic merit. A photograph proves whether the producer “has art” or whether he has not. That is why I wanted to see 12 prints. Photographers here and there have “fluked” a single “masterpiece.” That is the curse of photography. No one could do that in any of the graphic arts—he must be a master craftsman to produce a masterpiece.

Now pull up your britches and take in your belt and send me a dozen or 20 prints that is a good feller. There is to be no comparative criticism in my “history”—this is odious — I will not even give an opinion on them —all I need to see is enough to put you on my list of artists. You need not compete for my medals—they . . . will be marked hors concours if you do not wish to compete. . . . No one but you has refused yet and I have all the artistic photographers on my roll —many from abroad. But I have not finished yet not by a long chalk.

I have tried to write legibly and hope I may have succeeded. Wishing you a quick return to health and with kind regards—

F aithfully yours

P. H. Emerson

I don’t worry whether you work for money or not—all that concerns me is the art in the photographs.

Then he received from Paul Rosenfeld his Port of New York, which is a collection of character sketches and especially laudatory of Stieglitz and his works. In a rage he wrote Stieglitz:

5 Lascelles Mansions Eastbourne Sussex

June 21st, 1924

Dear Steiglitz

You I think mistook my letter and probably Paul Rosenfeld has written to you he sent me his book and in that book he made the absolutely misleading statement that in Camera Work is a full record of all the most artistic photographers. I wrote to him and pointed out that this is a terrible mistake for him to make for many of the best photographers are not in it at all. . . . Six of the very best are not included in it from the index published in Manuscripts. I said nothing about you or your work or it except that. A terrible mistake for any responsible critic to make—a mistake which damns ruin on a critic at once—mistake which you admit and which I am sure you would not have liked to be printed. All this scribbling on ART Photography does much harm and there comparisons are odious and futile. I don’t care whether you have an art theory or not—nearly all great painters have had theories—even Whistler and the great painter Hogarth spent much time in words at a theory— in the Analysis of Beauty. Painters work out their theories as they go along where they are going, whether they realize it or not. For example you have one principle “pure photography”—But all that does not matter—all that matters is the merit of the photographs.

[He then announces he has 12 b&w prints from nearly all the men worth considering, and that most of them have had difficulty in finding 12 really fine prints, for every 12 had a few weak ones that had to be replaced. Most of the best men are, he finds, very modest] —except for that vain and conceited little puppy—Coburn—who is not a great photographer and never will be (This is all private.)

I still get no photos from you nor any definite statements or whether you will not send me some. I would see some of your landscapes, and “songs”—if you will oblige I shall be glad and grateful.

I hope you are better,

Yours faithfully— P. H. Emerson

Then, apparently having received a note from Stieglitz which pleased him and soothed his anger:

June 26, 1924

Dear Steiglitz

I feel sure your health is returning for I see a glint of humour in your letter—sorry I can’t send you some words of wisdom how to get more and more health from your side.

I shall trouble you no more about prints. I say nothing of your recent landscapes for I have not seen even reproductions of them. Now I have the opinions of three competent persons (two artists and one photographer) upon them which is the next best thing to seeing them myself—for I can trust the opinions of the artists.

I hope the country life has completely restored you to health and if you change your mind send the prints along—or send a parcel to the RPS as a gift —so that if they be what is claimed by some of your friends they may be a prime [?] influence—so please don’t say I am wrong, or may be, about the landscapes. I have not given any opinion on them.

Cheerio. Yours faithfully.

P. H. Emerson

Silence for some months—or perhaps Stieglitz did not save the letters. Then:

Oct 1st 1924

Dear Steiglitz

That terrible production the ‘Playboy’ reached me and I thank you for sending it to me. I don’t wonder at lunacy being in the increase in the states when these terrible things are done in the name of Art. I see a reference to your cloud pictures—it is the photos I want to see and not ‘puffs.’ A chap called Hoppé has been puffing you over here and calling you the ‘arch-pioneer’ and as I am writing history I should like some legal evidence in what direction you have been a pioneer—bar the ‘fuzzytype’ I know of no pioneering of yours. Perhaps you will enlighten me. He who drives cattle should himself be fat and Hoppé’s production is that second-rate and where it’s appeared prove my theme that he has no art. If you get in with that crowd of German-Russian aliens you will go mad. ‘Playboy’ has given me a headache and as Pennell said of another publication it is the work of ‘incapables.’

How are you —I hope your health is better. Send along those photos and don’t be shy. Clarence White sent me a batch of his work. In fact now I have had photos from all but two or three who are really artists and they have promised.

Pure art photography is very very difficult to do—that I have learned and that is why all those chaps run off to gum and oil and jazz photos and fuzzytypes etc. I have been wading through acres of drivel on art and sacks [?] of photos and there is very little gold when the washing is done.

And following up:

October 3rd 1924

I wrote you yesterday on receipt of the terrible production the Playboy was it—it went into the waste-paper basket. The little part about your “Clouds” does not interest me at all —a man who edits a monstrosity like that does not count and the very fact that he puts his name as editor to it proves that his opinion is worthless.—You seem to fail to see this. As I said before if you get a favorable opinion on those cloud prints by an artist like Colike or Whistler let me see it.