Be-ing Without Clothes: Neither Nude Nor Naked

Be-ingness and Ideal Form

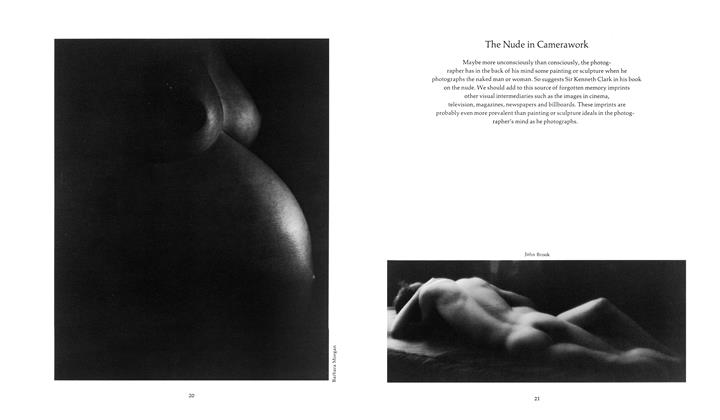

The critical background for this exhibition was Sir Kenneth Clark's definitive book, The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form (Doubleday and Co., Inc., Garden City, N.Y., 1959). How generous a parade it presents of mutations of the nude and naked in art from antiquity to Henry Moore. Conzzzcerning photography, Clark observes: "Consciously or unconsciously, photographers have usually recognized that in a photograph of the nude their real object is not to reproduce the naked body, but to imitate some artist's view of what the naked body should be." We should add to this source of forgotten memory imprints all the pictures a photographer sees, from cinema to billboards. Any visual intermediary will affect a photographer's approach to the unclothed figure. Acknowledging varied visual influences, we noticed that the photographers' handling of the less than ideal human form, disturbing in its imperfection, had a certain common denominator. In numerous satisfying works a certain "taste" for something different from the classic proportions and poses of the nude in art appeared like a promise. The persistence of that taste suggests that a different aesthetic should be defined in order for the concept of ideal form to accommodate the medium of camerawork. This essay moves toward the clarification of such an aesthetic. Its preliminary formulation reads: "being without clothes, neither nude nor naked."

Clark demonstrates in his book that ancient Greek sculptors and painters found an ideal form to symbolize the gods in the alteration of the proportions of the human body. We may observe a comparison of these changed proportions in a Christine Enos picture (page 66). The proportions found during the years 480 to 440 B.C. satisfied for centuries the inner longing in mankind, particularly in artists, for the Perfect. Man liked to find himself mirrored in the work of men. During this time it was felt that the beautiful body and the beautifully trained athlete were fit models for gods. Christianity changed the relationship of man to God : the hero turned into the monk. The only subjects the medieval painter and sculptor depicted without clothes were Adam, Eve and the crucified Christ. The magnificent ideal forms of ancient Greek statues changed drastically to depict fallen man. New ideals had to be invented. The bellies of Adam and Eve protruded like bulbs from the earth. The spindly legs could barely support their weight, and the mystery of sex was guarded by the fig leaf. Nonetheless, these were ideal forms satisfying some gnawing hunger deep in the soul of the Dark Ages. Ungodlike as they were, Adam and Eve were never as ridiculous as today's Everyman in front of the camera with his bodily inconsistencies and bumps. During the Renaissance, according to Clark, Michelangelo loved the form of the human male as much as did the ancient Greeks. Michelangelo mirrored an attitude of his period — a time in which the most noble aim in art was to give human form to the dying Jesus and the resurrected Christ.

Contemporary man has turned away from images of gods and goddesses, Adam and Eve, and the Resurrection with the result that he is in desperate need of spiritual regeneration today. It is not gods and parents who have died, as man today often claims - it is man himself who has gone to sleep on a collision course toward world destruction. Twentieth century art and photography prophesy something of the sort. Painted, sculpted, or photographed nudes are regularly tortured beyond belief or reduced to principles of geometry that destroy the Phoenix - power of regeneration. What goddess could ever hatch a Brancusi egg? Or what god could play swan to Bill Brandt's Ledas?

Why or how Man has turned away from his spiritual birthright is the subject of Seyyed Nasr's book, Encounter of Man and Nature: The Spiritual Crisis of Modern Man (Allen and Unwin, Ltd., London, 1968). He reasons that after alchemy was profaned and became chemistry, and astrology was profaned and became astronomy, then putting man above God would lead to the present crisis proportions. Over a century ago Charles Baudelaire foresaw that photography would profane art. In the midst of the growing crisis, a handful of photographers have gone against the stream, struggled to prove that camerawork is at times a form of psychological alchemy; at times subject to the outer forces astrology seeks to understand; at times, a form of prayer. Camerawork, as opposed to profane photography, is a concerned force in the spiritualization of man. The nudes of Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Weston lead in that direction. They celebrate the splinter of divinity in the body, the substance which leads toward spiritualization.

From one of Clark's ideas, "The nude is not a subject of art, but a form of art," we find a crucial stepping stone toward an answer to our question of whether we might find an extended concept of the "nude" in camerawork. We wondered if being without clothes might be a form of camerawork. If so, what kind of form? If the "nude" were a form of art and the "naked" a form of life, then "be-ing without clothes" would have to be a form of camerawork that was neither "nude" nor "naked." With those restrictions, what remained for the model in front of the camera to do, except be? While both art and photography depend upon the undressed model, photography is the more dependent. A comparison of the attitude of contemporary painters and photographers toward the model will be useful in developing a concept for camerawork, which relates to the unclothed human being. The painter uses the model for the qualities of the flesh, but he does not necessarily have to depend upon the model's vitality. If the model happens to be awake, the situation or encounter may be much more stimulating, but the painter does not have to energize the subject's livingness or thought. He has the power through his artistic talent, his mind and his hand to make the drawn line or incised stone come alive while the model remains inwardly asleep and thoughtless. The photographer has the power and the talent to make his model come to life. In his creative state he works with, not from the model. In his creativity he is, and when he is, his model can be.

If the photographer and the model are of different sexes, both parties are likely to feel stimulated, energized, vivified rather than tired after a camera session. Painters and photographers are often moved to have sex after intensively photographing or painting the naked figure. As Clark has suggested: "Nature has a way of surpassing Art." There is an alternative. The sex stimulation may be turned to its other function, the nourishment of inner growth. If the photographer makes that turn, the interpersonal period when he and the undressed model have only a camera between them may become one long meditation. The photographer initiates the meditation when he introduces a thought that the two can develop together. In fact, the quality of the thought determines whether intercourse is stimulated or spirit fed - orgasm or insight.

Clark writes concisely concerning thought appearing in the nude in art: "the miracle of Rembrandt's Bathsheba, the naked body permeated with thought, was never repeated . . . Moreover, this Christian acceptance of the unfortunate body has permitted the Christian privilege of a soul [italics ours]. The conventional nudes based on classical originals could bear no burden of thought or inner life without losing their formal completeness. Rembrandt can give his Bathsheba an expression of reverie so complex that we follow her thoughts far beyond the moment depicted; and yet these thoughts are indissolubly part of her body, which speaks to us in its own language . .

Can we say that “the naked body permeated with thought“ may be photographed? That the camera may see the thought? That the photographic image may reveal the thought? In this essay we continue to say “yes“ to these questions. For example, consider the images photographed by Michael Kliks (page 23) or Arnold Henderson (page 39).

The concept of thought defines our formulation clearly. Neither nude nor naked, be-ing without clothes means the presence of thought in the body that vitalizes the whole human being.

The Family, the Ideal Form, and Revolt

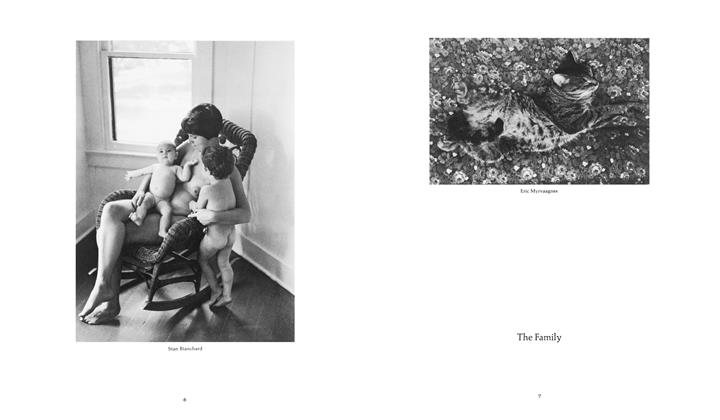

We would like to point out the pictures that compose the two gestalts mentioned earlier: first, the family; second, the search for an ideal form and its tormented opposition. We will consider initially and briefly the family because it seems to take ideal form in its stride: the family is satisfied with its concern for contact with flesh and the communication of lovingness by touch.

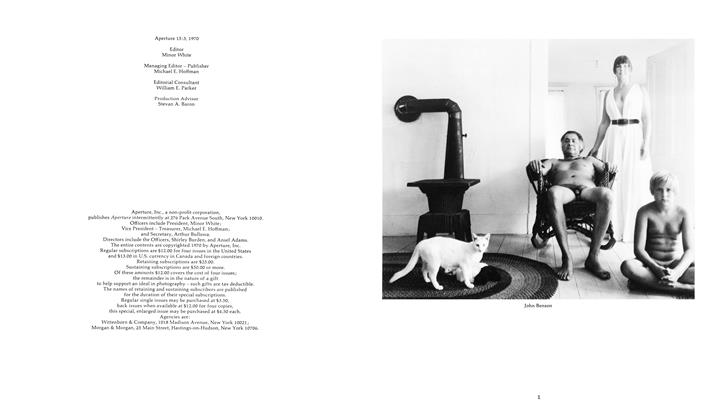

John Benson (page 1) updates the “long hard look" characteristic of the photographs of itinerant photographers in the Great Plains almost a century ago. No less honest, yet with fewer clothes and more humor, Benson's family is unmistakably 1969 A.D., unquestionably being if not be-ing, and particularly photographic. Father and child images such as that by Karen Tweedy-Holmes (page 12) are rare and so we wished we might have shown one of Walter Chappell's, but the father's erection would not pass the barrier of “public morals." Mother and child are often photographed both during and after pregnancy: Barbara Morgan (page 20) in the classic manner and Goodwin Harding (page 15) in the contemporary manner of subject related to environment. Charles Renfrow's photograph of mother and daughter combing their hair in the bathroom (page 14) is an example of the careless, random cinematic treatment of an undraped pair. For many photographers today the casual attitude extends beyond the family to groups of youth in varied activities. In Stephen Siegel's photograph of a "blind walk" (not in catalogue) on a path in the woods, blindfolded photographers are being led by nude models of both sexes. Richard Wynn's photograph (page 17) is full of the joy of being alive - ideas be damned, the thought of joy is enough.

If there is love and humor in the family, there is also sarcasm. Leslie Krim's floating nude in a corner (page 37) is suggestive of punishment. Richard Kirstel's photograph of a woman with a group of dolls around her (page 36) is one of a long series intended as a dream sequence, but the image has its own reality and could suggest mother as psychological manipulator. Another photograph which functions symbolically is Leslie Krim's "Two Bicycles in a Room" (page 78). The naked man on one bicycle is more wrapped in plastic hose than the ancient Greek Laocoön is in serpents. The woman sitting on the other bicycle is unencumbered by clothes or coils. We can make up our own story of how soon the pair will part.

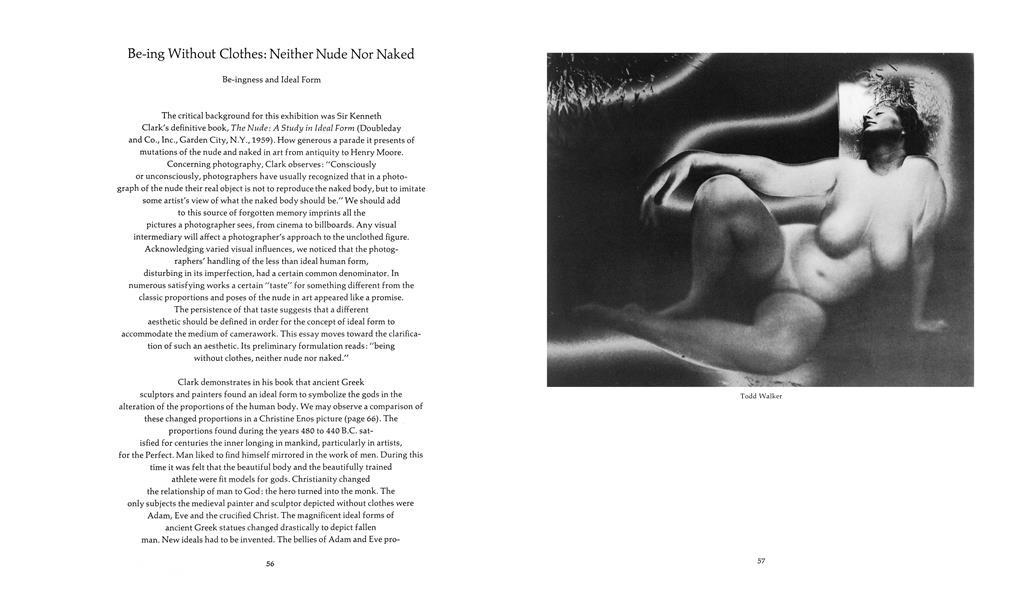

The second gestalt, the ideal and its opposite, the tormented denial, requires more space. Examples of emulation of the classic nudes in painting (Todd Walker, page 57, and James Jevne, page 60) or classic images in photography (Goodwin Harding, page 63) are in the minority. The majority of the photographs take the negative side of the search for ideal form, frequently in rebellion against art, camerawork, war or some other aspect of society.

We should consider the evidence of revolution through imagery at some length because the great-grandsons of the PhotoSecessionists are again using the medium for revolt. While their great-grandfathers pitted an ideal form against Philistinism in photography, the current revolt looks like a dismissal of both the Philistine and the ideal form.

Although carelessness is the order of the day among the great-grandsons, now and then we see work among the inherently creative twenty-year-olds that evokes the sense of personal authenticity that has always been the watermark of art. Many students are discovering that when the uniquely photographic print fails, some derivation from the original negative may evoke the very feeling that inspired them to expose in the first place. With such experiences repeated often enough, who wouldn't begin to doubt the supremacy of the pure photography tradition?

Carelessness in art or photography amounts to scuttling the standards and canons of a cultivated class of society, thus instantly eliminating that class from its accustomed authority. The uncultivated assert their supremacy in many fields today: folk music, rock, the music of John Cage, solarized prints, sandwiched negatives and all the rest - leaving the authorities of taste out in the cold. Much contemporary work disregards the standards of unique photography without a second thought. “This is the way it is,“ they say, as they offer black-edged prints of undressed people for evaluation. How is the symbolism of the funeral actually meant? As a revolt against twentieth century technological materialism? As a symbolic burying of outworn forms? As a wish to avoid the kind of deaths a war society promises?

Without standards, or with non-standards accepted because they are the antitheses of the traditional ones, it becomes possible to depict graphically with the image of the naked body disgust, resentment, and downright "No" to malpractices in society - though, what the photographer "shoots" with a camera is never quite as dead afterward as what he hits with a bullet. The current settingaside of traditional standards in photography is evidenced in two processes at once: a manifestation of revolt and, at the same time, the unrest out of which fresh, ideal and viable new standards will spring.

Revolt by art is an old practice. Clark cites the dumpy, nude, middle-aged women which Rembrandt etched to protest the superficial prettiness of his contemporaries. He also cites Picasso, who shattered the human form in Cubism, and Rouault, whose paintings of prostitutes are sufficiently ugly to inspire us with fear. Be-ing ugly, at times, is. Clark says, in reference to Rouault's prostitutes, ".. . in the lukewarm materialistic society of the 1900's, absolute degradation came closer to redemption than worldly compromise. But the curious thing for our present purpose is that Rouault should have chosen to communicate this belief through the nude. He has done so precisely because it gives most pain. It has hurt him, and he is savagely determined that it will hurt us . . . and yet Rouault convinces us that this hideous image is necessary." In photography, the revolt must be against the human body itself. Often revolution in art only shatters an idea or symbolic representation of man. When camerawork destroys an aesthetic form through the image of the unclothed human form, it torments the viewer's flesh at the same time. By the power of empathy, our own body and bones are wrenched, dismembered or tortured. Robert Heinecken (page 83) commits in his work a savagery comparable to Rouault's prostitutes.

PhotoGRAPHIC rendering techniques (Benno Friedman, page 73) which were suspect a decade ago are commonplace and enthusiastically practiced today. Usually masked beneath the guise of beauty or a didactic "This is the way I like it," not all tormented images are born of conscious revolution. Too often the dismemberments seem to be imitating the fashionable. There are a few instances (Paul Wigger, page 50) when the device of disturbing human proportions or substituting the substance of paper for the substance of flesh powerfully evokes psyche or inner growth.

The pictures of disfigurements of the human form are arranged in a tentative progression. Whereas Robert Boni's image (page 64) shows flesh, Arthur Freed's (page 65) destroys flesh and empties the body of substance, leaving a shell of form. Bill Brandt's images in his "Perspective of Nudes" frequently destroy the flesh - the critics say, for the sake of design ; the psychologists say, to either kill us or remind us we are dead. Brandt distorts in the wide-angle-lens-manner shown in this book by Thomas Weir (page 43). From Brandt, however, one gets the feeling of a search for some ideal form through abstraction in the manner of Brancusi or Arp. For Weir the distortion seems to originate in the hope of an affront to sensibilities for shock value alone. At the same time, his wide-angled women symbolize a misshapen society, upholding false perceptions of reality.

Cut and dismembered bodies are manifested in the work of Allan Dutton (pages 69 and 71) and may symbolize man's desire to manipulate the world to pieces. Edmund Teske, with double exposures, illustrates the distance between man and woman as seen in an opium dream (page 70). Graphic additions to the body, as used by Eric Kroll (page 76) and Benno Friedman (page 73), express keen delight at surpassing the limits of unique photography. They seem to be trying to escape from the sort of pictorial self-consciousness found in Norman Lerner's black girl (page 72). They both substitute selfexpression for self-consciousness in their additions to a medium that, left alone, promotes consciousness of self - which does not hinder marvelous image making. The general euphoria of Friedman's bathers (page 68) radiates be-ingness.

The Sabatier effect, often mistakenly called solarization, in some mysterious way lends a quality of aesthetic distance to Arnold Doren's work (pages 75 and 82). This distance may be interpreted at one level as a restlessness or disappointment with unique photography, and at another level, as a driving desire to remake a world with camera (or a bulldozer if he had one). In other instances, the Sabatier effect clothes the unclothed body by substituting photographic tone or value for flesh (James Jevne, page 60), thereby converting a being without clothes into a nude - distant, idealized, therefore more respectable. James Jevne's model draws the solarized tone around her like a cloak, elevating her ecstasy. The body may be seriously distorted (Charles Swedlund, page 81) or reduced to blobs (Eric Kroll, page 76). Finally, the body disappears. If an eventful transformation takes place (Charles Swedlund, page 85), the body is not recognizable as a body, but only as a metamorphosed image that seems the embodiment of light in photographic silver.

Robert Heinecken's work has steadily evolved from photographically stripping a woman to imagistic dismemberment of her body. At one point his photographs of the body were pasted on the six sides of loose cubes: the observer could rearrange the woman at will. Whether this satisfies a hatred of women, a compassion for the breakdown of a woman, or furious anger at her is not necessary for the observer to decide. This destruction symbolizes brutalized societies so distant from humanity that such vicarious blood-letting is a crying delight.

Dan McCormack (page 79) dismembers the human body in a cooler vein. He reduces it to buttons and makes pleasant decorative designs that soon resemble keyboards and other mathematically precise forms. If this is not the ultimate of inhumanity, it comes close. One is reminded less of communal man than of IBM man or of a hole in a piece of paper. He symbolizes another human truth: each man or woman may be compared to a blood or nerve cell contributing its part to the good of a whole society.

From this rather lengthy description of the ways contemporary photographers agonize the human body, we also should point out that their work relates also to a larger aspect of society. VVe would speak of this as a photographic reflection of the “spirit of the times.“ Clark stresses the point differently in his statement: ".. . thus modern art shows even more explicitly than the art of the past that the nude does not simply represent the body, but relates it, by analogy, to all the structures that have become a part of our imaginative experience. Greeks related it to their geometry. Twentieth century man, with his vastly extended experience of physical life and his more elaborate patterns of mathematical symbols, must have at the back of his mind analogies of far greater complexity. But he has not abandoned the effort to express them visibly as a part of himself/'

Part of what the twentieth century has related by analogy to the nude is a death wish, a Götterdämmerung on a huge scale. According to Clark it was announced by the Romantic poets and painters of the last century and brought to fullness in this century by science and technology. The images of some photographers imply a taste of the future more than a wish to topple used-up structures (Seth Kobb, page 88, and Michael Fredericks, page 89). Their revolt is against this twentieth century death wish. Others appear indifferent: in their expression of be-ing they oppose nothing (Peter de Lory, page 16, Irene Strauss, page 9, and Paul Wigger, page 49). If God wants to destroy the world, all He has to do is leave man to his own devices.

Other contemporary photographers claim to be merely following their likes and dislikes, that is, working blindly. When they work blindly something in their unconscious takes advantage of them, laughing at their likes and dislikes. Without their consent, the temper of the times uses their eyes for its eyes and their images for its prophecies. As we started work on the exhibition, the symptoms of working blindly first appeared as psychological sickness to which remedies must be applied. Then we began to see these sick images in the larger context of the natural turning of cycles. It was as if the photographers, unconsciously reflecting cosmic forces, were caught up in that stage of society's evolution that marks the end of an era. We called this negative gestalt "Everyman's Götterdämmerung."

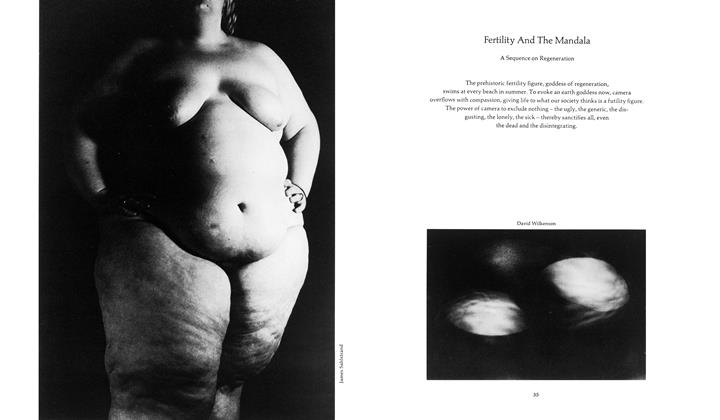

A number of sick images gathered around James Sahlstrand's "Earth Mother - Enormous" (page 34). Hence this image opens a series in the catalogue that might be called Regeneration. Of the fat woman we were tempted to say, "Yes, my boy, we have polluted everything." A revolting figure, she attracted, like Venus, other images of alienation around her - to mother them. These follow in the catalogue. Then a transformation took place in us. The fat woman turned into a prehistoric figure of fertility; reminiscent of Elie Nadelman's dolls she became the eternal motherhood figure full of nourishment, embracing everything, growing old with giving. The vision arose of ten thousand ancient cultures, of millions venerating what we call the ugly.

The knowledge that the fat woman is a photograph led to insight concerning the process of camera be-ing without clothes itself. Nothing is excluded in camerawork and compassion will flow for everything alive and struggling, beautiful and reigning, defeated and dead, ugly and working. Camera sanctifies death and blesses life because both are parts of the same cycle - what dies must be born again. It seemed for a moment that camera bestows fertility continuously upon the futility figure of the fat woman, and she in turn nourishes the frightened, the despairing, the arrogant and the perverted clustered around her. Her dark earth powers, like camera, like the great Mother Nature, filled us with compassion. Only our eyes were offended by the ugly shell.

The downward direction of the sequence begins to turn upward with the implication of intercourse by Arthur Freed (page 46). The image suggests that darkness may become light during the act of intercourse: regeneration at some level may start with the sexual act. The symbolic form of the turning point of regeneration occurs in the double exposure image by James Marchael (page 47). By this double exposure or double printing, Marchael establishes a relationship between the physical and spiritual union of man and woman. The image also reveals the Jungian animus and anima in every individual. A man's engagement of these two in himself can be the turning point of regeneration. After that comes the struggle to unify the conflicting forces in us. Paul Wigger's picture (page 49) may be read either as a vision of victory over inhibitions or as the spirit rising from the dead. His picture (page 50) is the first reaching-out for the vision. Linda Connor (page 51) and Sandy Hochhausen (page 52) have loosened ties from figures and caused them to float. The flapping wings of Charles Swedlund's image (page 53), pathetic as they are, symbolize our primary efforts at regeneration. We wonder how we, by our efforts, can ever be regenerated. Herbert Hamilton's "Mindloge I" (page 54) shows a way: by meditation. Hamilton's image is not an ideal form, but rather the image is a tool, a mandala, the study of which is symbolic of esoteric "centering."

Toward the Future

Perhaps some images of the future are already here. According to George Gurdjieff, Nature always casts her artists before her. Thus the photographers chosen by Nature will be in some measure prophetic. Are the Laurés (page 90), the Alinders (page 91), the Bensons (page 1), the Fredericks (page 89) and the Chappells (page 59) straws in the wind?

Scholars have observed that modes of expressive art correspond to the temper of the times, and changes in periods of art and society are speeding up. These periods once endured beyond a man's life span. Shifts now come so often that periods are shorter than a man's lifetime. Instead of thinking of the epoch as stable and man as changing, we must consider the environment and society as shifting, and know that somehow each man must, if he can, find stability within himself. Dare we say that a search for "be-ing without clothes, neither nude nor naked" would lead to the discovery of that stability within oneself? We do! We do because we see an increasing number of younger photographers who somehow act as spokesmen for the rest, presenting "manifestoes" of intentions that may be summed up as follows:

Camera is indifferent to how it is used. It has a kind of holy detachment. Greyness, smudges, brilliance, bent corners, splotches, accidental movement marks are all the same to it. To the River Ganges it matters not whether a herdsman fords his cattle, or the retinue of a prince crosses with jewelled ankles. Camera has its own characteristics and among them is the ability to emulate or echo other arts and crafts, including dream analysis, painting, poetry, sculpture, music, dance, weaving, pottery and marksmanship. I have chosen photography as my medium. I will select the segment of its spectrum which fits my likes and ignore the rest if I wish. When I feel like painting, I will jiggle my camera, take out the lens, sandwich negatives or anything else that occurs to me. If I want to explore the unimagined images hidden in my negatives, I will solarize, reverse or combine in any way that suits me. Above all, I am as wary of these distinctions as camera is indifferent. It's all photography to me, including drawing and talking and loving. Photography is my medium and I don't care how I use it or how it uses me. Anyone who accuses me of being unwilling to accept the descipline of unique photography simply doesn't know that photography can be, or that I embrace camera because it frees me to be.

Taking a last overlook at be-ing without clothes, we observe that a map is not a terrain. Neither the catalogue nor the exhibition embodies the process of "being neither nude nor naked but filled with thought." This is Everyman's prerogative in the process of living. It is, therefore, both a subject and a form of camerawork.

Be-ing without clothes seems to belong to youth. Paraphrasing Clark, the body is beautiful in swimming before it is beautiful in camerawork.