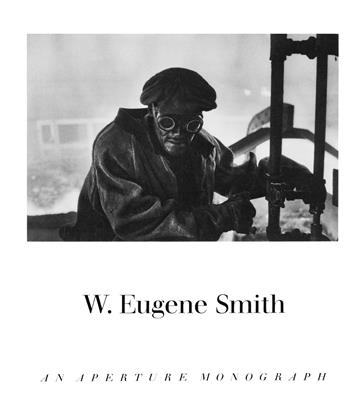

W. Eugene Smith

Success or Failure: Art or History

I. Biographical

Gene Smith first used his camera at age fourteen for aerial photography. Within a year he turned himself into a pursuer of current events, a reporter for the Wichita Eagle and Beacon. These were provincial heartland papers informing those heirs of the pioneers, who, invading that 'dark and bloody ground,’ had penetrated to our Middle West a century before. They, like old John Brown in his Mosaic mania toward abstract justice, absorbed with due violence a Puritan ecology from the Plains: flatness—no mountains, rigid decency, poverty, possibility, adventure. In the Twenties, there were no longer buffaloes. Indians. Brown’s nor Cantrill’s raiders, but sport still—plus aviation. In 1927. Charles Lindbergh, a middle-class. Middle-Western youth with something of a radical political heritage, gave the world an apologue for unlimited possibility in our conquest of space and time. But this was also the Dust Bowl era. when pioneer heirs learned to starve in silence or push on, past where their forefathers had first settled, to an even more forbidding Pacific coast. An ungenerous land once promising milk and honey framed images of the plagues of Egypt: starving families in rusty jalopies, cattle dead in the dust, migratory workers. This was visible testimony to the rewards of a century of Anglo-Saxon white Protestant psalm-singing. Smith as a young photo-journalist burned all his early prints and negatives; they were inadequate in focusing on the bitter epoch in which he was raised. Modesty, or awe. was born; a burden of indignation outweighed the innocent placement of effective or facile images useful to journalism. Later he wrote: “I had an intuitive sense of timing, an impossibly poor technique, an excitement to the fact of the event rather than of interpretive insight. Although I was deeply moved I did not have the power to communicate it.”

Smith, about fifteen, already ached with the discrepancy between “art” and “life.” In paint one might struggle with a recalcitrant medium, overcoming initial clumsiness by digital mastery although the mechanics had little enough to do with vision or endowment.

In photography you had to make the shutter’s click capture a legible (and symbolically strong) image as fact. Continua of facts make history but are neither significantly graphic nor beautiful in surface or pigment. Ilis failure to satisfy as an artist was now salvation as a photographer, and not for a last time. In 1936. his father killed himself. Daylong, nightlong disasters; drought, dust, business failure sapped pioneer energy. At eighteen. Smith, long before he could accurately define a failure in The American Dream, was haunted by its ghost in his own house. His father was dead. How? By whom? Why? When? Where? What docs journalism fatten on? Murder and suicide. Naturally, local newspapers sniffed this small fact: the irrelevant, forgettable, expendable detail of some guy (named Smith?—not Jones, nor Brown). Why did a perfectly sensible man do a silly thing like that? Son, why did your daddy do it? He had so much to live for. Or did he?

Eugene Smith was educated early in a hatred of journalism, the apt shabby techniques of sob sister, feature writer, their colleagues with cameras, whose increasingly professional rape of privacy must dog Gene Smith for thirty years since he would, perforce, try to make a living beside them. But also art can be the prize snatched from such mortality as his father’s. James Joyce fused fact with fiction in the context of Roman Catholicism in desuetude. Perhaps this doesn’t apply to Kansas, but when young Stephen Dédains, a rebel trembling on the threshold of art as a career, is taunted by his clever friend—Your mother’s lousy dead and you wouldn’t even pray for her—we hear an echo. What prayers prevail. Roman or Baptist? Your father is lousy dead; make something out of the lousy life which did him in. With a camera. I shall indict my father’s murderer or fix the black magic of his, and my, self-murder. While newspapers, weeklies thrive by soiling us with their information, nevertheless, there must be a continuing dialogue. One must speak to another, many others—the world. Few are saints, martyrs, or artists. But let a working historian tell it how it was and is. “How could I remain to work in such a profession of dishonesty?”

Thus demanded our indignant young Kansas Calvinist. Revenge murder by disdain? Avenge Daddy by silence. Noton your life. Life? (Life?)

Smith was convinced by a friend on a newspaper that “honesty is not a profession. Honesty consists of what the individual brings to his work.” Silence is golden, but the blank page tells no tale. So this naive postulant got himself a “photographic scholarship,” created uniquely for him, at the University of Notre Dame.

In 1937, aged nineteen, he had enough of the strictures of disciplines which were then possibly more medieval than they might be today. Nevertheless he had been taught—and he learned. He came to New York to the big life. To Life, a weekly magazine, large format; progressive pictorial journalism beckoned. When before in our civilization had the double page spread offered a surface so worthy of significant images? Shortly after, Smith joined the staff of Newsweek. Life had seemed too raw, too sensational, not in “good taste” to that class of luxury advertisers whom Henry Luce was astute enough to disdain. Luce, pioneer publisher, the smartest since William Randolph I learst, let Newsweek glean those politer pastures of domesticated comestibility. Newsweek offered its readership a trace less rough, a bit more squeamish, smelling of that genuine gilt-edged American phony—Family Circulation.

In 19 38, W. Eugene Smith was fired by Newsweek. which had its own morality, for Smith had done a bad thing. He had used a miniature camera. You don’t use a small camera, boy, for a big magazine. Or at least a magazine bucking to be big as Life and twice as polite. You sell automobiles by the big sound the doors make when they bang, bigly, shut. That Rig Door Sound. Apart from the elementary fact that small cameras can spy on or seduce those moments from history which Newsweek was eager to purvey, pictorial journalism as then practiced seems primitive now. Smith was broke; he free-lanced. He was soon offered permanent assignments. After all, he took pretty good pictures. But he preferred to risk starving than do hack work which only turned his stomach. He didn’t exactly starve. He got jobs—from Life, from Colliers. The New York Times. The American.

But now, oddly enough, he found the very use of his miniature camera hampering. Already it was a tool he had mastered. Hence he could discard it. He was becoming overly conscious of technique. He found himself getting dangerously artistic. There were problems: artificial light and a factitious employment of the multiple flash. Was he letting himself be victimized by that very freedom for which he’d fought?

In 1939. whichever muse it is that governs photography said:

“Gene, you’ve been a good boy. You’ve used your eyes. You have fair eyes and a trigger finger. Rest them. Also, you have two ears. Listen.

The measure of music is a means of dividing, marking, analysing—time. Music may whet your vision, which can be dulled. Gene, do thou listen.”

What does music mean to most artists (i.e. visual or plastic practitioners performing today) ? A few poets, composers, and dancers listen to records as if they were something more than a background for small talk, aural interior decoration, or an additive to dings. That fancy hi-fi set, costing whatever its components cost, blasting away, wall-to-wall plush listening but not hearing; noise fused in flannel non-music. Yeah, hut the beat, man; the beat. Contrariwise, Smith took music as metric; its structure, its ambivalent syncopation, its return to order in opposition, its dialectical balance. Its very insistence, sharpened hand and eye. In 1939. he signed a retainer contract with what was then, after all (and all was quite a lot) and what is still, the most progressive mass-circulation weekly. Life.

In 1940, he married. A year later, impatient with the rut of assignments, he resigned his contract, attempting to find again some individual, idiosyncratic identity. It’s hard working in a factory; it’s doubtless hard even for the editors. Sometime, somewhere, there must be picture-editors with a sense of personal gift; sometime, somewhere, there seem to have been good prose-editors. Richard Garnett slaved for Joseph Conrad, whose native tongue was Polish; G. B. Shaw illadvised T.E. Lawrence. The services of that editorial saint. Maxwell Perkins, are well-known. No one could ultimately salvage the mindless rhetoric of Thomas Wolfe, but Perkins was friend and collaborator of Scott Fitzgerald. Neither Life nor any of the other magazines have been often distinguished for comprehension or encouragement of mavericks like Smith. They are not patrons but publishers. It is naive to believe that they can be much more—same as Hollywood. However, in the hope that they might be. photographers are still encouraged to take good pictures, some of which get published. Choice or sequence are rarely those pleasing photographers. At this time. Life, jealous master and notable slave driver, naturally nettled by Smith’s recalcitrance, warned him that if he was quixotic enough to throw up this contract, he could expect no further mercy from the Luce-machine.

But 1942 was wartime. Smith was in a position to elect his assignments. Now, thirty years later, he accuses himself of misusing his hard-earned liberty because of creative or rather moral immaturity. “I made . . . brash, dashing, ‘interpretative’ photographs which were overly clever and with too much technique . . . with great depth of field, very little depth of feeling, and with considerable ‘success.’ ” Although these shots were conscientiously taken and analyzed to discover his own possibly unique service, they were still within the fairly strict limits of acceptable mass-media journalism. Yet he was always trying “to find himself.” If this was vanity or dispersal of energy, while his considerable facility continued to make him feel somehow guilty, the problem of identity for commercial photographers remains: Who am I? Am I a photographer? Am I an historian? Am I an artist? Can I be used? To what limits do I pay for my use? Is my use, on any terms, always to be diluted?

Understanding so well the debasing mechanics of stop-press necessity, he managed to feel ashamed of work which later might have pleased him more. Such shame is either self-indulgence or the sole pay an artist-photographer or journalist-historian can award himself. In his own eyes, Smith repudiated his work; true, he had taken some fine pictures, but conditions prompting their taking were a violation of that luxurious qualification which for lack of a better definition he would always consider as freedom. To a man with a simpler soul, equable nature, or more modest energy, such a restriction might seem priggish and puritanical. Worse, eminently impractical. The few good pictures, or rather, the few pictures with which their taker was pleased, were paid for by endless ratiocination: dissatisfaction with those that hired him. with himself for letting himself be hired, with factors that forced the hiring.

Then, there was a real war. World War II. as distant today as the campaigns of Marlborough or Wellington. In between, there’s been Korea: the immense obscenity of Vietnam. But World War II was. after all. not a phony war. hut Hitler’s war. And the Pacific—

Pearl Harbor—Tarawa—Rabaul—Eniwetok—Iwo .Tima. Gene Smith was invited to join Commander Edward Steichen’s group of U.S. Navy photographers, hut. apart from the fact Smith possessed no education (i.e. a parchment testifying four years attendance at an accredited college), he suffered from poor eyesight—also other physical lapses and a difficult character. Hence he was disqualified as “impossible” by the solemn idiots of the Navy, who debarred him from observing the death in battle of better educated boys.

However, fortunately, wars arc worse run than Time, Life, or Newsweek. As fighting hots up, rules relax. In 1942-43, Smith found himself briefly as a war correspondent in the Atlantic theater, joining the staff of Ziff-Davis publications. He rejoined Life in 19 44. Whatever else is said. Life made the best pictorial coverage of any wars within its life. Gene Smith saw the Pacific. He was party to many island invasions, on the unlucky thirteenth of which lie was seriously wounded. “I would that my photographs might be, not the coverage of a newsevent, but an indictment of war—the brutal corrupting viciousness of its doing to the minds and bodies of men; and that my photographs might be a powerful emotional catalyst to the reasoning which would help this vile and criminal stupidity from beginning again.”

Herein lies the disarming failure in Smith’s photography. EIc considers his pictures of Saipan and Iwo Jima failures. That is, he could not show on a plain paper-surface coated with chemicals, in a snapped shot—the plump immediacy, savor of fright, grief, sadism, fun, and luck of war. Who can make an image to be saved from oblivion, emanating from a vivid orgy? Painter or photographer? Leonardo and Michelangelo failed to distill much tragedy in competitive patriotic cartoons celebrating a famous Florentine battle. They did display glorious gigantomachia, which long served as academies for the heroic male nude. What was war to them but a fair pretext to demonstrate the glory of athletic manhood?—Tragedy? Not remotely.—Heroic? Possibly theatrical; certainly beautiful and absorbingly interesting for technical virtuosity. Picasso’s gigantically overestimated composition for which the bombing of Guernica was pretext is not tragic, nor exemplary (except plastically). It is an entré acte curtain in tasteful grisaille for an unproduced ballet. Its graphic ingenuities have moved no one to tears—Picasso least of all. Now it has become merely a world-famous object, postcards of which are sacred souvenirs. That art is life, a substitute for life, or a program for living is a pious 1 ie. perpetuated by museums of modern art, wherever they may be found. For men of lesser gift and greater guilt or stricter morality (like Gene Smith), battle is also a bloody game. But he was unable to spotlight it in an arcane proscenium or narcissistic sado-masochism on the level of an art-historical palimpsest. Smith, in spite of his skills and presence in thirteen assault landings, failed to capture that moment of truth in one of them, which rendered an image as memorable as Picasso’s, although from his own words this seems to be what he was attempting. Woodrow Wilson did not make the world safe for democracy even by a first world war; Smith failed as has everyone else who attempts to make didactic art out of sudden death or mindless murder. Painters seldom have such ambitions; they are more preoccupied, modest, realistic in the matter of intellectual analysis. Smith differed from Picasso, and it was not only the difference between painter and photographer. Heroically, Smith with his meager equipment, a camera, lacked the tradition of structures of Western art, the services of postCubist analysis, the prestige of museum-culture, and an enormous visual ingenuity. He merely waited for invisible batteries masked by ragged palms to shoot the shit out of him and his friends as they hit the beach. Now he says he thinks this was a waste of time since marines are still getting shit shot out of them. I do not think his pictures from Iwo Jima and Saipan are negligible. Some of his shots, while they certainly prevent no future war, serve to remind us what this particular

war was like. They will serve as attractive footnotes to those overtidy histories which generalize war; they are miniature diamond-hard pebbles in a vast human mosaic.

Who needs such photographs? Life paid for them as it has tens of thousands of others. They were not particularly well-edited. Few felt Smith’s shots were different in quality from many other reporters.

But Life glamorized their daring representative and canonized him with a full-page portrait, his body completely swaddled in bandages. Given his ethic, naturally he was crushed by the inadequacy of his camera, his failure to capture what he d actually lived. Smith failed as a philosopher, not as a photographer. No picture, however sadistic, pornographic, or aesthetic, starts or stops anything. Michelangelo’s Last Judgment did not salvage the Judeo-Christian ethic. Mathew Brady hardly prevented another Gettysburg. Art has its place, proud or pitiful. Possibly photography is an art; at least photography is now more artful than most painting. The camera hasn’t the potential for synthesis that has been demonstrated by digital mastery governed by visionaries in manual contact with stone, bronze, or paint. Photography is a branch of social science, if indeed there is such a measuring—and history. I hey may be the same thing. Certainly science and history employ artistic techniques. But contemporary obsession with the so-called creative act has swollen photography by idiotic snobbery which has the presumption, since both camera work and etching are classified in museums as graphics, to equate Rembrandt with Stieglitz and Goya with Brady. Greedy and pretentious print departments in our busier museums claim any image on paper as the equal of every or any other image on paper. This results in three generations of photographers whose activity is, from an aesthetic or qualitative judgement—nervous, compulsive, indiscriminate, self-imitative, mechanical, ingenious, and tiresome. It has stimulated curatorial energies; every print by everyone is an artifact, as significant as any Egyptian shard from some dubious and repetitive dynasty—significant only from the fact that it exists. Dominated by a condign conspiracy between mass media, coffee-table publishing, luxury-advertising, and competitive curators, photography since the Korean War has declined into ferocious overexposure. Possibly every click of every lens everywhere in the world would have a statistical significance were it reduced by computers to incidences of apathy and mindlessness on every map. Possibly there has been an advance in color, over-printing, tricks, and (ultimately) modest gimmicks. Photography has followed the example of the tradition of automatic writing, the stream-of-consciousness used without consciousness or conscience. A quivering aura of tedium, the factitious prestige of the after-image hovers over most contemporary photography, which a caricaturist (like Max Beerbohm) could have penned: the ghost of Gertrude Stein, a stuttering mother-image presiding over the suicide of Ernest Elemingway, setting on his oft-wounded brow a bull-horned crown of thorns labelled “Success.”

So for Gene Smith, his shots at Saipan and Iwo Jima failed. lie condemns them; who with better right? Had it been left to me,

I would have included very few others and quadrupled those admitted here. Anyway, he proceeded toward work that held greater personal satisfaction. He went through a lot more personal hell returning to work for the big-circulation magazines, where, in spite of everything, is the lone place professional photographers make a living. Ele was told he would have to prove anew his capacity to fulfill certain standards and requirements. Times had changed. New styles were needed. New styles of coverage. Life had to keep up with the times. Lije. The Times. Time. The very quality or strength which had made Smith’s name condemned him now to a file marked “Smith.” A hospital is not the worst place in which to learn self-development. After several months spent thus from 1947, he emerged, healthier, to embark on a series of picture-essays that included “Folk Singers,” “The Country Doctor,” “Trial by Jury,” “Hard Times on Broadway,” “Life Without Germs,” “Recording Artists,” “Nurse Midwife,” (the very famous) “Spanish Village,” “The Reign of Chemistry,” “Charlie Chaplin at Work,” and “Man of Mercy” ( Albert Schweitzer in Africa).

Samplings of these picture-essays are shown here. It’s too bad they can’t be seen on that scale for which they were first conceived. Those which have been chosen may be better printed than when they first appeared, but now they are very much smaller. Doubtless, their graphic or plastic values are closer to Smith’s intention even reduced as they are. But the overall effect on the big pages, rough and grainy as the presses made them, loses immediacy. Only “The Country Doctor” retains full value in its generous pathos: that icon of exhaustion. For significant failures, since Smith seems to revel in his particular brand of unsuccess,

I cite the essays on Charlie Chaplin and Albert Schweitzer—not pictorially, but for Smith a treatment of the mask of mortality. Llere are two of our most charismatic archetypes, world-famous victims— seduced, corrupted, defamed, historically betrayed by mass cult, mass media, and a passionate lack of ironic historicity. Here is spelled out, once and for all, that genius for didactic exploitation, the formula unconsciously following guidelines instituted by William Randolph Hearst. developed by Henry Luce. Supremely well stage-managed, reproduced, distributed, here is the rape of the innocent image.

Chaplin: greatest comedian of his time, casting himself as a failure through the confusion of compassion and irresponsible self-indulgence, corroborated by the publicity departments of the studio he almost knew enough to control, reduced to a grotesque expatriate basking in self-pity and a vacuous sunset. Schweitzer: in his youth, seeker of the “historical Jesus;” servant of Johann Sebastian Bach; traduced into a monster of self-indulgence; prey of an army of magnetized, voracious journalists, dedicated to perpetuating his ruthless paternalism and primitivistic methods. Schweitzer, framed in the persistent, picturesque atmosphere of an unchangeable jungle, administering homeopathic pity: retarded, retardative. No saint, but a powerful ego, vain as a movie star or canonized symphonic conductor, whose self-seduction was greased by every aid from Lije. Look, Paris Match. Der Stern, and those other hundred eager scavengers. Squadrons of reporters sent out by the big weeklies served owners and publishers, who were also, and in fact, supporting Love, the core of the Judeo-Christian ethic, in its precipitate decline. Was it by accident Henry Luce was the child of missionaries to the (Buddhist) heathen? Did not the world still need saints and martyrs, if not canonized by a church in decline, at least self-elected and blessed by the chrism of publicity? Chaplin, the martyred exile; Schweitzer cast as Bach-SocratesJcsus—could have, to the eye schooled in the irony of historical metaphor, been illuminated in the full aura of their metaphysical desperation. Instead, the compassionate camera man fell into the well-placed trap. Chaplin had not staged the greatest contemporary tragicomedies for nothing; he presented himself as he wished to be type-cast, with a minimum of make-up. Schweitzer was indeed theologian, organist, country doctor, missionary to the blacks; a sacred monster, in the line of freaks of dubious religiosity which stretches from the Abbé Liszt, through Richard Wagner to Billy Graham. And let us not, in any negative enthusiasm, condemn Time, Life, or Fortune for the rewards or opportunities they offer. Fame and adventure arc paid for generously. Editors allocate no assignment to those unwilling. The trick is this (as all tricks of the devil are) : to offer seemingly unlimited chances for capturing the sources of power (material or spiritual), and then due to circumstances beyond their control, to edit that very truth-telling essence right out of existence. The conditions of journalistic photography, its undivorceable marriage to advertising, and the vacuity of public taste ensure this. And it is “beyond control” if you conduct mass media. Ultimately it is the photographer’s choice, not his editor’s. The Luce-machine is not the devil, not even today amid our general apathy. Less and less, defeated by a more powerful horror, T.V., is it The Enemy. But the wizard’s promise of unlimited accessibility, with the fatal need to dull those edges a true poet must always require, corrodes any person confused in his gifts. Few survive such promises—journalist or historian, critic or photographer; everyone, including the readership, blames the machine rather than his own essential apathy.

This is by way of no judgment on W. Eugene Smith. Nor is it his biography. This is already too long an essay on why this book is a failure, why all such are bound to fail. A full account of Smith’s life would be too painful to read or write.Few practitioners of his craft anywhere have survived his portions of personal misfortune, disaster, suffering. “Trying to keep going, to continue without turning from my photographicjournalistic stand, from those standards, those beliefs in photography I would demand of no one else.* Trying to continue my own small kind of personal crusade which is many things beyond being a photographic photographer.”

What was the epitaph over Fitzgerald’s Gatsby? “The poor son of a bitch.” What must be the epitaph of anyone who tries greatly and modestly fails? Nevertheless, I do not believe that Smith has lower standards for other men’s work than for his own. If so, it is disquieting. Those who press beyond the tried analysis of their limits after a normal period of daring and enthusiasm waste themselves in repetitions of failure, trials which have not paid off, which will never be solved by reiterating formulae. Picasso boasts: “Je ne cherche pas; je trouve.” It can take a lifetime to recognize limits, but it is a waste of muscle if, through conscious suffering, one learns nothing but compassion. That, dictionaries say, means suffering with another: fellow-feeling, sympathy, pity inclining one to succumb or spare. Inflated images of beloved pre-digested, tenderized popular types, not as they are in history, but as they are industriously blown up to be by an avid, avaricious permanent Present, feed on the reverse of Compassion, which is Self-Pity. To most, glancing through the pages of Time and Life, compassion means: I’m sorry for me.

Who has the right to make such drastic or dispassionate judgment? You don’t hit a man when he’s down. We live in terrible times. Gene Smith has been one of their more capacious witnesses. But, for the sake of argument, and, since this is an essay about photography, may we not, indulging in the sport of analytical speculation, ask ourselves why this collection does not add up to more, and not alone this particular book? Why docs every photographic book and almost every portfolio, however fairly edited or produced, amount to something less than one might have hoped from the energy, money, talent, technique expended? Photography, that is individual shots by professional photographers ( films are something else), too often impresses us as delinquent craft.

‘Author’s italics.

Dr. W illiam H. Sheldon, in his classic Varieties of Delinquent Youth. analyzes the problem, not—as does our dictionary—as neglect of duty (whose duty? judged by what or whom? ). but as the failure to fulfill certain expectations which, governed by long attentive analysis, might lead to a belief in some inherent, specific, unexpected potential. Delinquency in art today is general; the history of twentiethcentury painting, prose, and to a large degree poetry, a century from now will be less concerned with several isolated, memorable works, but rather with the exploitation and distribution of numerous momentarily negotiable personalities by casuistic mechanisms. Photography as an art form is a special case of delinquency. Much was expected; more came to be claimed. More was hoped from its putative services than any invention involving eye and finger since brush and chisel. It would surely replace painting; it only replaces portraiture and the battle picture. In our epoch, brush and chisel are judged officially obsolete. Instead, as franchise, we have drop, blot, splatter, or its reverse in hard-edged, paper-taped stencil; the ragpicker’s bag, the junk-yard welder’s torch. Metric in verse has been replaced by wan idiosyncratic “sensibility”; if a sold is sensitive, perforce his feeling is sincere, the feeling itself distinguished chiefly by the length of its typewritten line. The same follows equally for the structures or non-structures of aural mechanics in which melody has been outlawed along with verbal metric in a series of academic specifications which would have left Sir Joshua Reynolds breathless. Indeed the camera, quantitatively speaking, has been able to leave us more memorable images which stick in the increasingly unretentivc eye than the dreary successions of periods of a dozen modern painters, whose lively obsequies arc regularly, efficiently, tidily, and fatally celebrated by accelerating series of retrospective shows at all those museums of modern art. Atget. Lartigue, Sander, Evans, Brassai, Strand. Caponigro, Gene Smith, or any personal favorite you nominate mean more, even in terms of plastic visual values, than the preponderance of painters, inflated past all limits in their vastly more pretentious and eager delinquency. But the potential of photography, the parochial prestige of the photographer, has been outrageously shored up. past any early promise or eventual achievement, except in those realms of scientific measurement, where human eyes are physically incapable of penetrating. But, except for museum curators, scientific photographs do not share in the hierarchy of art, except by accident or ingenious manipulation.

Photography as science (including the landscape, as in the woodland and stream pictures of Caponigro), photography as history (as in the picture-essays of Gene Smith) is always youthful and attractive. But its unhappy flirtation with art depends on pretentious perfectionism, genteel embroidery. Imperialistic curators devoted to collection and classification are no friends to photography. They acquire samples, as if they were stamp collectors. Everyone must have his triangular Gapc-of-Good-I lope, his surcharged U.S. penny ( 1871 ). Prints are filed alongside thousands of papery companions. Key photographers since the start were painters— Nadar, Steichen, Man Ray, Cartier-Bresson, Walker Evans—not great painters, but men comprehending the problems of rendering forms on a plane surface by hand and eye. Ancestral magicians (like Stieglitz, that Albert Schweitzer of photography) pushed the medium into a prestige of graphics past any real potential. From the ambitious areas they prophesied, on some level with Rembrandt or Goya, we cite its present delinquency: chiefly breasts and bellies, bumps and holes, hills and hollows at the disposal of Hugh Pleffner and the photographic advanceguard of luxury advertising.

The dictionary defines pornography as uThe description of the life, manners, habits, etc. of prostitutes and their patrons; hence, the expression or suggestion of obscene or unchaste subjects in literature or art.”

W. Eugene Smith is not a pornographer, but rather something more frightening and attuned to his time. He is a pornocratic photographer.

The dictionary defines pornocracy as uThe dominating influence of whores. Specifically: the government of Rome during the first half of the tenth century.”

The photographer’s service is not that of the lithographer, or etcher manqúe, or an embroiderer of trifling surfaces. His greatest service is the seizure of the metaphorical moment. History is constructed from documents; even the liveliest must be interpreted. This is not a task for him who first does the documenting. Documents testifying to the syntax of Cicero, the placement of caesurea in a line of Horace, the development of Marlowe’s iambic pentameter, or the invention of an oil pigment capable of being stored in tin and hence portable are keys to history. It is hardly by accident that W. Eugene Smith is a pornocratic historian.

His times require him. As Rome approached the year 1,000. as we approach the year 2.000. worlds split. Byzantium had smashed the simple atomic unity of a Western civilized empire. (Barbarians were simply people who could not speak Greek.) What was promised to the people of Constantine’s inheritance for a second millenium, since Jesus had signally failed to fulfill his absolute promise of love, forgiveness, peace, redemption, was a state in which assassination was the accepted policy of constant, instant coups d’etat, where potential prime ministers were systematically castrated to ensure their clerical careers and soldiers were promptly blinded as reward for their service to the basileus. Imperial whores ruled from the Golden Horn. Naturally, the end of such a world was expected with some enthusiasm. The Eastern empire had endowed Rome with that shattering schism from which it never recovered. At the present, our pornocracy makes noises about an ecumenical theology in all the spasms of its senility, but this is more like an Appalachian conference of inefficient Mafia-types fending off untidy anarchy than real belief in any compassionate authority of a prince of peace.

It is to the world of 2,000 a.d. to which Gene Smith’s pictures address themselves. They may have their small if solid use by that world then to show our world now. Brady for 1861 -65, Atget for 1895-1910. Cartier-Bresson for 1935-70, Gene Smith roughly for the dates of this album. But Smith is different in kind; none of the others were hysterics.

It is that element of controlled and sometimes uncontrolled hysteria which blesses Smith s best shots with aptness. Hysteria, tlie enemy of nihilism, a clean suggestion that things have gotten out of hand, smolders in Smith’s most memorable prints. And, except for his war pictures, there is little enough violence; rather, a brooding calm before a presumed, inevitable explosion.

II. Autobiographical

I have a personal pornographic or pornocratic anecdote to tell about W. Eugene Smith, whom I met in 1940 and whose photographs I admired more than any American, save Brady, Walker Evans, and Alice Boughton.*

In 1942.1 was about to go into the Army. I had a friend who shall be namclessly called Jerome Peters. He was a reporter for Time. Ele came to interview me about the ballet, a traditional form of virtuoso theatrical dancing based on antique academic disciplines. He claimed he wished to know about the relevance of ballet in wartime. Could ballet be expected to survive with Western Civilization at stake? Could ballet withstand Hitler? How many homosexuals were there in my company? Would they claim draft-deferment? I asked him if he were referring to queens or dikes; if so, did that sincerely interest Henry Luce. Oh hell; you gotta get your story. This reporter had a sensitive approach; he had been to Cornell. He was sincerely (and he meant sincerely) interested in The Dance. So was I, and for lack of a better term we became “friends.” Indeed I wanted a story in Time about male dancers. George Bernard Shaw, and Lenin before him, claimed an exemption of male performing artists from combat since their national service was in an exceptional virtuosity. So Jerry Peters and I became moderately intimate; we drank late. We didn’t talk about the fucking war; we talked about fucking. He had a walk-up in Yorkville. One night I was inspired to outline a Time-style story with a switch which might get it past the Gossip Department editor. Ballet was skill, a metaphor for Freedom for which we were (almost) all fighting. Jerry was a little hysterical; when drunk, he got mean. Fie was pro-Nazi in his liberal-radical style; handsome and tubercular. Also crazy, in an uninteresting way. One thing he would not do was get himself drafted; sure his lungs were touched, but he wasn’t sure how long this would stick for a 4-F disqualification. We indulged in one of those conversations about whether or not it was ultimately efficient to avoid the main, leading, or most significant events of one’s epoch with lots of Jack Daniels. Finally he admitted he would tell ’em he was queer rather than get shot up in some idiotic war. He wanted to be a writer; he knew a lot about how Time worked; by God, after the war, or whenever, he was going to sit down and write the exposé of what shit Time really was. His rather small room had a door which ostensibly led to the john. He asked if I really had to go. I said I could piss out the window or didn’t his can flush? Reluctantly he unlocked the door. What a relief! Suddenly, around the walls, I saw that they were completely papered with photographic proofs filched from Harry Luce’s files. They were Gene Smith’s shots of Pacific landings, recounting in detail the end of several young men ’neath frayed palms. Some were blurred, others clear; some had their typewritten labels still pasted on. Obviously they were pornographic; did Jerry sit there and amuse himself by shots of Tarawa? I came out of the closet and said something about Gene Smith being our contemporary Mathew Brady.

‘Illustrator of the great “New York” edition of the novels of Henry James, whose Photographing the Famous appeared in 1928.

He sighed: “Now you know. I can’t take it. I’m scared. Did you see those pictures?”

“Yes,” I said, “beautifully composed, like Rembrandt or Goya.”

Jerry yelled: “You ignorant bastard; they’re real.” He was getting nervous; so was 1.1 said I assumed they were from a feature-film produced by Henry Luce. He yelled louder: “Now get out; if you tell anyone I’ll kill myself.” No need, for like one of those abrupt, untragic deaths in E. M. Forster’s novels, T.B. took him two years later.

However, in his bathroom, before I’d ever seen a battle, I saw what Gene Smith had seen. A chapel for private devotions, creamy with guilt and fright, had emblazoned upon its walls some mini-pix Michelangelos. Gene had found and fixed one Last Judgment. Here was the pornography of murder—in which Jerry Peters had no share. Modest bacteria would claim him; until that moment he might dawdle on his can, confessing to gods of shame and death. Smith’s icons were no palimpsest of tasteful torture. An historian had been sent to the Pacific by a commercial enterprise in the service of an imperialist power. He had taken his camera. He had seen stalwart, excellently trained and equipped boys atomized in an Eden-like landscape. He had recorded what he’d seen, not by accident, nor yet as a roving reporter, but with a nugget of grace allocated by some dispassionate godhead, who. disallowing compassion, unoccupied with salvage or salvation, whispered: “Gene, my servant, show it how it is.”

Gene did. Maybe Jerry Peters, a penitent sinner of 1943, was partially pardoned by the recognition of truth in those extremities of action he was too lame to emulate, but who himself was also a forgiveable victim. Whatever Gene chooses to think of himself, it is not compassion residual in his photographs I most prize. In our day—since World War I. the Spanish War, World War II. Korea. Vietnam, the Middle East; the various ends of the Kennedy brothers, civil-rights workers, Black Panthers, Martin Luther King, and the many more murders about to break above us, an inevitable repression which will make McCarthy’s inquisition look like a picnic—compassion won’t mean any more: I’m sorry for me. I see Gene Smith’s best photographs as icons, like those thank-you pictures painted by grateful craftsmen, set up as tokens before altars of their favorite name-saint intercessors, who saved their lives from tuberculosis, mad dogs, or an automobile accident. Without self-pity or vanity. Possibly hysterical. Possibly insane. Memorable.

May 4, rpdp

Lincoln Kirstein

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Bibliography

Winter 1969 By Peter C. Bunnell -

W. Eugene Smith His Photographs And Notes

Winter 1969 By Lincoln Kirstein -

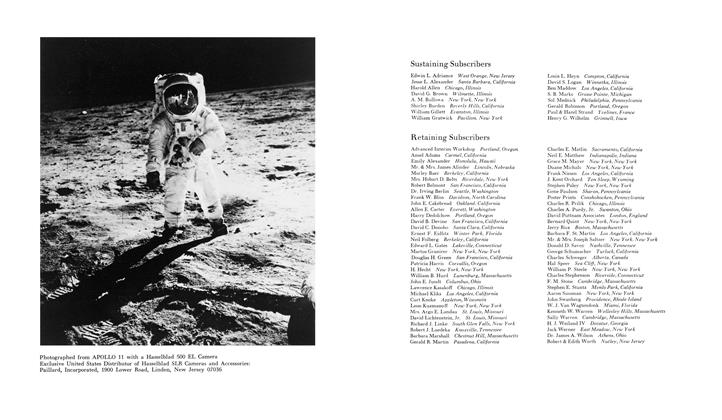

Photographed From Apollo 11 With A Hasselblad 500 El Camera

Winter 1969 -

Aperture

Winter 1969 -

Woodstock Music Festival At Bethel, New York 1969

Winter 1969 -

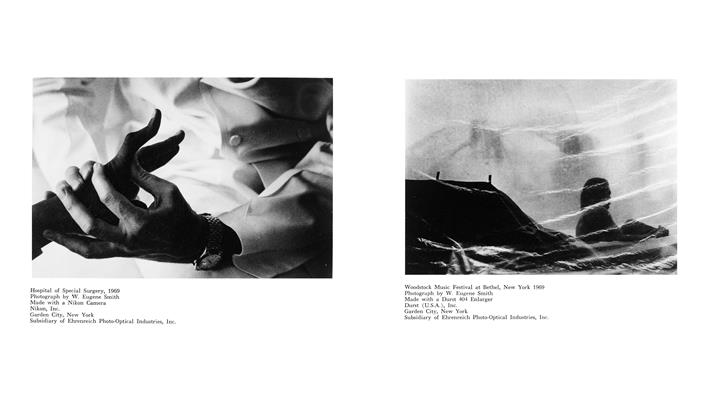

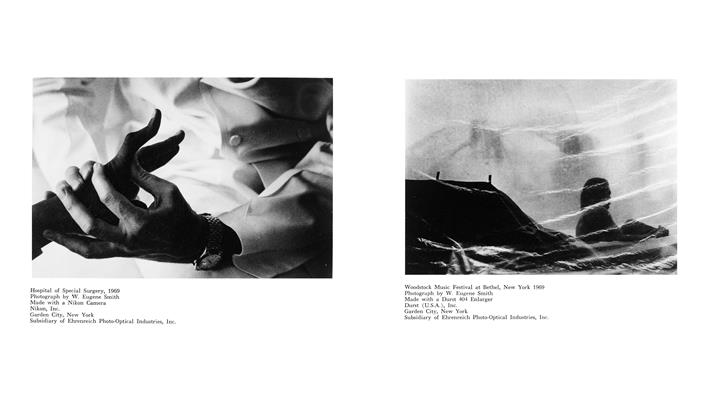

Hospital Of Special Surgery, 1969

Winter 1969