Uelsmann’s Unitary Reality

Wiliam E. Parker

Suggesting that the photographic medium and the camera’s instantaneous moment for arresting permanence from transience precludes the photographer’s opportunity to reconsider, transpose, eliminate, or augment, the Newhalls have written: . . the masters are unanimous:

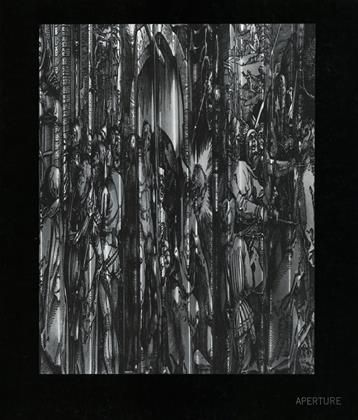

the photographic image must not be tampered with. For them, the work of any human hand is clumsy, any piecing together of negatives glaringly false, any cropping not envisaged before exposure an admission of weakness.” 1 If the case is such, these canons of insistence for the pure and unaltered photographic form are being superbly challenged by the composite prints and amalgamated images created by Jerry N. Uelsmann. Exemplary of reemergent interest in the vivification of reality through transformed photographic representation, Uelsmann’s work has received remarkable acclaim. Perhaps this acclaim has developed naturally from a revision of aesthetic canons in our time, a revision that seems to insist that media have no innate limitations and that creative integrity is posited in the form and not the man. More likely, Uelsmann’s recognition is a testament that excellent photography will include, within its proper function as art, transformational processes and images capturing enduringness through synthesis and augmented recognition. Uelsmann, a recent master, extends the photographic potential, amplifying directions reminiscent of the past and projecting the future significance of a type of creative consciousness involved in camera work.

The techniques Uelsmann employs—among them, combination printing, the negative sandwich, and “blends” —recapitulate processes focused paradigmatically by the mid-Victorians: Price, Rejlander, and Robinson. Also, Uelsmann’s photographs share the process spirit, if not the cross-media extremes, of explorations in photomontage and collage originated by amateur artists in the 1860’s and cultivated with intensive vigor by representatives of Dada, Surrealism, and the Bauhaus in the period between the two World Wars.2 This is not to suggest that Uelsmann’s extensions of composite techniques resurrect

1 Newhall, Beaumont and Nancy: Masters of Photography, George Braziller, Inc., New York, 1958, p. 10.

2 For further information see: Gernsheim, Helmut and Alison: The History of Photography, Oxford University Press, London, 1955, Part the “High Art” 3 pretensions and allegorical-pictorial banalities which so charmed Albert and Victoria’s favorites. Nor do such extensions reanimate the predominant inversively negativistic, irrational, or abstract-constructivist tendencies of later art concerned with severe amalgams of fact, pure form, and fancy. Uelsmann’s composite techniques engage the past, yet enable the realization of a richer pictorial ethic and recognition of the real.

Whatever significance informed the compound “failures” of the Victorians may be reinterpreted as an archaic préfiguration of a perception which Uelsmann, extending the inherent capacities for veracity in the photographic medium, brings to bear with greater creative insight and moral clarity: the fact that life’s richer forms, emotions, and events are seldom caught whole in the pure linearity of existence, but, in art, may become unified in their right and proper perspective as conjunctions of forms, emotions, and events. In Uelsmann’s art, profound psychical and physical awarenesses of interconnections between varieties of experience are merged into composite recognitions. The differentiated inconsequentiality of “things” is made consequential; the irrelevant becomes relevant: first, through the initial glimpse of affinities between an infinite number of diverse realities and their coordinate imagistic potentials or equivalences; second, in a creative process which couples the discontinuous clarity of previsualization (the automatic and final fixing of the perceived and conceived in the shutter’s release, as Weston suggested), and the continuous vision of postvisualization, Uelsmann’s term for the intuitive observation and reintegration which takes place in the darkroom— that other milieu wherein the processes of vision continue the alchemy of discovery and transformation, synthesis and conjunction.4 Contrary to uniquely individuated research, the Victorians sought to court concomitant forms in painting (anecdotal realism) by composing images “made by Nature” (the photographic pastiche) in order to achieve a “virtuous” and competitive representationalism. For example, H. P. Robinson, in a humorous essay, thought that photography could accomplish an unparalleled mimetic reality only if one recognized that though the medium cannot lie like paint, it has the merit of approaching it in mendacity; and, paradoxically, in its capacity for imitating nature and bending to the creative will, photography is the most perfect art of all.5 Uelsmann, however, seeks to reveal an authentic representationalism, employing the most appropriate medium for the forms of his search and, unlike his forebears, creating composite images wherein the paradoxical and anachronistic realities we sense as “presences,” yet cannot commonly “see,” are made visible and very much the truth rather than illusion. Ultimately, Uelsmann’s photography is a regenerative clarification of a creative consciousness which must have been dimly felt, but not adequately visualized or conceived by earlier exponents of the photographic sensibility.6

IV. The Collodion Period, 16. “High Art” Photography; Gernsheim, Helmut: Creative Photography, Boston Book & Art Shop, Massachusetts, 1962, Chapter XIX (The Influence of Surrealism). Also, Coke, Van Deren: The Painter and The Photograph, The University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1964, pp. 23-27.

3 The term is from Gernsheim, Helmut and Alison: The History of Photography, Ibid.

4 The reader may wish to refer to extracts from a paper entitled “Post-Visualization” by Jerry N. Uelsmann, read to the Photographic Education Conference in 1965, “Jerry N. Uelsmann; Composite,” Camera 46: 1, 1967, pp. 6, 19.

5 See Robinson, Henry P.: Paradoxes of Art, Science, and Photography, Wilson’s Photographic Magazine, Vol. 29, 1892, pp. 242-45, included in Lyons, Nathan: Photographers on Photography, Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1966, pp. 82-88. Robinson states: “The truth that is wanted is artistic truth—. . . . Artistic truth is a conventional representation that looks like truth when we have been educated up to accepting it as a substitute for truth. ... it is sometimes said, perhaps jokingly—. . . —that photography cannot be art because it has no capaciy for lying. Although the saying is wrong as regards our art, this is putting the semblance of a great truth in a coarse way. In other and more polite words, no method can be adequate means to an artistic end that will not adapt itself to the will of the artist. The reason is this, if it can be reduced to reason: admit that all art must be based on nature; but nature is not art, and art, not being nature, cannot fail to be more or less conventional. ... It is clear, then, that a method that will not admit of the modifications of the artist cannot be an art, and therefore is photography in a perilous state if we cannot prove that it is endowed with possibilities of untruth. ... to the artist there is no merit in a process that cannot be made to say the thing that is not. . . . from this point of view, painting is a much greater art than photography . . . but . . . photography . . . has a capacity for lying sufficient to enable it to worthily enroll its name among the noble arts. . . . Photography gives us the means of a nearer imitation of nature than any other art, yet has sufficient elasticity to show the directing mind, and therefore is the most perfect art of all. If we must have paradoxes, let us carry them to the bitter end. ... of the possible delinquencies and untruthfulnesses that art requires and photography can accomplish ... if it cannot lie like paint, it has the merit of approaching it in mendacity.”

6 As part of a more inclusive study of Uelsmann’s photography, I intend to define the implications of this creative consciousness, presenting an interpretive commentary on the origins and development of interests in composite techniques and combination printing. This future commentary will be concerned with innate psychological predilections for recording polysynthetic or syzygial views of reality operative in such practices prior to usually presupposed influences on and in their development, among the latter: Lake Price’s lectures and articles on art and photography; John Burnet’s Art Essays; Ruskin’s views on art and morality; H. P. Robinson’s influential Picture Making by Photography; and the naive intention which, seeking to share the pictorial aesthetic of anecdotal realism in painting, resolved itself in artificial photographic forms suffering, “not, as is commonly believed from a pictorial rela-

It is equally true that Uelsmann’s photographs appear sympathetic toward the alterations of representationalism residually endowed by later experimentations in art and photography, yet his exercised liberty in recording things as they are, or as they can be, does not emerge from expressive modes of protest, whim, or psychological catharsis. Nor does his instinct for a “freeing of processes” suggest an exotic attitude toward photographic representation destructive to the inherent integrity of the medium, which can, it is true, illustrate without alterational impositions. Only adequately interpreted, Uelsmann’s apparent inventions emerge from a declared romantic mode of creative expression, a mode which insists on being “involved with the celebration of life,” 7 not with its denial and disjunction. A sensitive response to his forms will reveal that they betray no essential opposition to the basic unit distinctions of reality one usually experiences; rather, as symbolic forms, they represent a verification of the conjunctive possibilities of mind and world. Though they may imply a reality that the photographer is presumably seeking to define for himself, the works are better realized in their plastic and imagistic presence, as a synthesis of personal and suprapersonal realities that are both credible and imaginative. Uelsmann’s photographs are identifications of a unitary reality realized in la matière première for the recognition and recording of intensified actuality in two-dimensional form. Law Whyte has stated: “The history of ideas is only in small degree a matter of the conscious choice of aims and methods. If it had to be that, it could not have begun at all. Ideas are not conscious inferences from experience, but orderings of experience, achieved largely unconsciously.” 9 Whyte has made equally significant observations in his provocative essay, “The Growth of Ideas,” from which the following fragments are recorded:

2

Jerry Uelsmann develops photographs which simultaneously link psychological and physical phenomena. If one accepts his expansion of the parameters of the photographic process to include transformations of unique forms and images resultant in composite orderings of experience, one might also approach the questions: what beliefs, feelings, perceptions, what philosophical attitudes, are foundations for his work and creativity? What views of reality motivate his forms? A note on the development of ideas and several of Uelsmann’s expressed thoughts may offer some initial answers.

Arthur O. Lovejoy, writing on the primary and persistent or recurrent dynamic units of the history of thought, remarks that there are “first, implicit or incompletely explicit assumptions, or more or less unconscious mental habits, operating in the thought of an individual or a generation.” 8 Sharing this primary view, Lancelot

tionship to reality, but from a bad pictorial relationship . . . ,” as Sidney Tillim has suggested in his article: “Walker Evans: Photography as Representation” (ARTFORUM, Vol. V, number 7, March 1967, p. 14). For the purposes of the present commentary, facets of this creative consciousness are expressed as Uelsmann’s work defines them.

7 See Kinzer, H. M.: Jerry Uelsmann: ‘involved with the celebration of life’, Popular Photography, November 1965, Vol. 57, No. 5, p. 180.

8 Lovejoy, Arthur O.: The Great Chain of Being, Harper Torchbooks, The Academy Library, Harper & Row Publishers, New York, publ. 1960, (Copyright 1936 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College), p. 7.

“Art, not school philosophy, is the most revealing expression of the state of mind of a period . . . The growth of an idea is a progressive ordering of experience, and all thinking consists in such ordering within the mind of one person. . . . man and man alone is creative in the richest sense, and he is this by himself as an individual alone with his creative imagination. ... in particular creative thought is an ordering process . . . Each phase in the life history of an idea necessarily occurs before its practical justification, just as a seed has to be formed before it can grow, and a plant grow before it can bear fruit. The idea has to acquire form in the plastic matrix of a human mind before it can spread out to reorganize his systematic knowledge, and this reorganization has to be accomplished before the idea can be communicated to, and accepted by, others.

. . . Through imitation we learn to understand what already exists. Through creation we come to understand something new.” 10

How strikingly parallel to the foregoing thoughts are Uelsmann’s comments on his own work and creative processes, published in late 1965:

“I didn’t just start doing these things for the sake of doing them. It was an effort for me to find a way of commenting on the world that the straight photograph couldn’t do; I had the need to make this kind of statement.

“A great deal of my discovery occurs in the process. ... I guess I’m a great believer in what some psychologists prefer to call the preconscious. That is, if I have the slightest inkling of a favorable response when I’m looking at proof sheets or doing some of the early explorations of these things, I go ahead and print it, and I live with it . . .

“These things are seeds. Some are reasonably well conceived things that I think will survive. Thy suggest a great many directions; all I have done is keep the process open to creative thinking at every stage . . .

“Much of life is an unresolvable thing. I like to present a problematic situation, and let the viewer in his inventive way come to grips with it on personal terms . . .

9 Whyte, Lancelot Law: The Unconscious Before Freud, Doubleday Anchor Book, Doubleday & Company, Garden City, New York, 1962, p. 3.

10 Whyte, Lancelot Law: “The Growth of Ideas” (1954) In Man and Tansformation: Papers from the Eranos Yearbook, Ed. by Joseph Campbell, Bollingen Series XXX.5, Pantheon Books, New York, 1964, pp. 253, 257, 262-263.

Sometimes I feel that I am on the first page of a personal visual dictionary that I am slowly evolving in an effort to define my own existence ... I get excited by every aspect of the process, and it brings me messages from the other world in a sense ... I somehow deal photographically on serious terms with this reality I’m trying to find and understand. . . .” 11

Uelsmann’s thoughts define essential aspects of his creative disposition. He views himself as the medium through whom an autonomous creative process continues and in whom an evolving reality is brought to bear and extended into form. He is the type of artist who is internally acted upon prior to the drama of external actuation.12 Rather than “will” his art, Uelsmann keeps the process open, fluid, subject to orderings of reality that are not only conscious and “known,” but preconscious and therefore truly objective and devoid of the personal limitations of adopted styles or devices. He has faith—if one will accept the term—in reality as it emerges from the flux of experience, in reality based upon evolvement and futurity, not upon imitation or the determinatives of limited conscious aims. He trusts archetypal sources which may be described as psychic potentials for form and meaning, prompting and contributing to the creativity of consciousness.13 In Uelsmann’s photographic process, these archetypal sources serve as guides and as tendencies, as motivational stimuli, whose affects are brought to conscious visibility on the pictorial plane as symbols. With these thoughts considered, one can recognize the essential ordering continuum from which Uelsmann’s work emerges. Initially, there is the emotive encounter with a “form as such” and the preliminary recording of its presence on film. The differentiated “form” is felt to be structurally and imagistically abundant. Later, in the darkroom, its structural and imagistic plenitude, affected by the insights and original actions of the photographer, impinges upon the potencies of other recorded forms. Ultimately, a conjunctive intuition in the artist, preconsciously animated by archetypal potentialities, recommends that mutually interactive forms be brought into union on a symbolic plane born from conscious and unconscious recognitions. Through the use of composite techniques, the formerly separate imprints of experience overlap their configurational, referential, and imagistic identities, are synthesized, and become, finally, a singularly symbolic and unified work of photographic art.14 This process may appear to dismiss the typical clinical procedures of the darkroom; however, Uelsmann has already spoken to this point, writing, “that many photographers avoid the darkroom as much as possible may be due in part to the fact that the mind is relegated to basic technical decisions. Some are even hostile toward it. . . . An indifferent attitude toward the darkroom is further reflected by the fact that many distinguished photographers do not do their own processing and printing. ... It is my conviction that the darkroom is capable of being, in the truest sense, a visual laboratory, a place for discovery, observation, and meditation. ... Let us not delude ourselves by the seemingly scientific nature of the darkroom ritual; it has been and always will be a form of alchemy. Our over precious attitude toward that ritual has tended to conceal from us an innermost world of mystery, enigma, and insight. . . .” 15 Regardless of what might be considered

11 All quotations from Kinzer, H. M.: op. cit., pp. 140, 178-180.

12 Carl G. Jung defined this type of creative disposition in his essay entitled “Psychology and Literature,” first published in 1929, particularly in his consideration of the visionary mode of artistic creation. To the point, Jung states: “Art is a kind of innate drive that seizes a human being and makes him its instrument. The artist is not a person endowed with free will who seeks his own ends, but one who allows art to realize its purposes through him.” From Modern Man in Search of a Soul, Harvest Books, Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., New York, first published in 1933, M.11.63, p. 169.

13 Again, Jung offers insights for consideration: “the archetypes, are as it were the hidden foundations of the conscious mind, or, to use another comparison, the roots which the psyche has sunk not only in the earth in the narrower sense but in the world in general. Archetypes are systems of readiness for action, and at the same time images and emotions. They are inherited with the brain-structure—indeed, they are its psychic aspect . . . They are thus, essentially, the chthonic portion of the psyche, if we may use such an expression—that portion through which the psyche is attached to nature, or in which its link with the earth appears at its most tangible.” (from Civilization in Transition, Collected Works 10, p. 31.). “It is necessary to point out once more that archetypes are not determined as regards their content, but only as regards their form and then only to a very limited degree. A primordial image is determined as to its content only when it has become conscious and is therefore filled out with the material of conscious experience. . . . The archetype in itself is empty and purely formal, nothing but a facultas praeformandi, a possibility of representation which is given a priori. The representations themselves are not inherited, only the forms, and in that respect they correspond in every way to the instincts, which are also determined in form only.” (—from The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, Collected Works 9, i, pp. 79f.). Collected Works published by the Bollingen Foundation, New York, N. Y. Jung has also written: “The creative process, insofar as we are able to follow it at all, consists in an unconscious animation of the archetype, and in a development and shaping of this image till the work is completed.” (—from Contributions to Analytical Psychology, Harcourt, Brace & Co., New York, 1928, p. 248).

14 Morris Philipson in his Outline of a Jungian Aesthetics (Northwestern University Press, 1963, pp. 27, 28) reminds us of the philological explanations of the origins of the Greek root word for “symbol. “In Greek, the word is symbolon. It is constituted of the syllable syn, which means ‘together, common, simultaneous with, or according to,’ and the word bolon, which means ‘that which has been thrown’; coming from the verb form ballo, ‘I throw.’ When the object called a ‘symbol’ is thought of independent from what it represents, the implication is drawn that it is constituted of elements that have been thrown together. . . . The symbol ... is part of an attempt to link a given known with an unknown; it is a content, available to sensory perception which would connect present experience with something that is not immediately available.”

15 Uelsmann, Jerry N.: “Post-Visualization,” op. cit. p. 19. Uelsmann’s statement that the darkroom process will always be a form of alchemy is most provocative. Uelsmann’s technical wedding of forms is accomplished as a further extension of symbolic fusion, utilizing a process which is similar to that which alchemists likened to the nuptial “coniunctio,” a symbolic ordering process in which divergent elements were amalgamated into one whole representing the mysterium coniunctionis of world recognitions with psychic recognitions. M. Esther Harding in her work Psychic Energy: Its Source and Its Transformation (Bollingen Series X, Pantheon Books, New York, N. Y., 1947, second edition, 1963, pp. 422-424) comments on

unusual procedures in the process of accomplishing conjunctive recognitions and in the imprinting of these recognitions in photographic works, Uelsmann informs others of dimensions of experience which they may have neglected, never accepted, or visibly misunderstood. At the same time he presents problematic situations marked for resolution in the eye and mind of his audience, particularly for those creative persons who may wish to share his search to realize a profound symbolic reality. It is to sympathetic observers that Uelsmann’s photographs are a compliment. For them, a confrontation with the attitudes and principles emanating directly from his work may prove further satisfaction to questions that have been asked.

“Enigmatic Figure” of 1959 (figure 1) is one of Uelsmann’s earliest composite images created technically through the use of the negative sandwich.16 Of early works in his development Uelsmann has stated that he was struck with the possibilities of uniting forms, particularly “to create a single image integration, to develop a compound metaphor for interconnections between opposites felt important, but as yet not fully understood.” 17 In this photograph and in “Mechanical Man” (figure 2) of the same year, imagery alone postulates Uelsmann’s concern for arresting a unitary reality. It is as if his first recognition of the importance of symbolical structure emerged in some chance manipulation of multiple negatives, the charge of possibilities discovered in the imprint of one image created from two. What was recognized became a basic and fundamental spirit informing the genesis of his first composite forms and a continuing influence in the development of his imagery. This fundamental attitudinal spirit conveys a definite emotion for viewing man and world in union, as one singularly total reality, cultivated through a synthesis born of a type of “monistic or pantheistic pathos,” 18 from which forms both physical and psychical are perceived and believed in as inextricably linked through consubstantial sympathies. Arthur O. Lovejoy has defined the psychological intensity of this type of emotion, which appeared early in the development of Uelsmann’s creative photography, in his comment that: “. . . psychologically the force of the monistic pathos is in some degree intelligible when one considers the nature of the implicit responses which talk about oneness produces. It affords, for example, a welcome sense of freedom, arising from a triumph over, or an absolution from, the troublesome cleavages and disjunction of things. To recognize that things which we have hitherto kept apart in our minds are somehow the same thing—that, of itself, is normally an agreeable experience for human beings. . . . when a monistic philosophy declares, or suggests, that one is oneself a part of the universal Oneness, a whole complex of obscure emotional responses is released.” 19 The release of creative energy in Uelsmann’s early work articulates that neither man nor nature, man nor machine, are limited particularistic identities. In “Enigmatic Figure” the semblance of a human form—walnut head, body of light—suffuses over the sinuous grain of wood, conjoined with fragments of leaves and lichens in a microcosmic landscape. In “Mechanical Man,” a technological portrait emerges—“bolt cover” and spectacles combining in an interpretation reminiscent of Rembrandt’s famous elephantine eye.

the alchemists search “in nature to see whether they could not uncover there a secret way of uniting things and adapt it to their purposes” and their varied processes engendered or “needed for making the aurum nostrum (‘our gold’) or the philosopher’s stone— in psychological language, the Self . . .” Dr. Harding reports that some alchemists “assert that nature unaided actually can make the stone, though it requires aeons of time and the process may be greatly hastened by art: ‘What nature cannot perfect in a very long space of time we compleat in a short space by our artifice: for art can in many things supply the defect of Nature.’ ” (See footnote, p. 424:6. From Geber, “Summa perfectionis,” ed. Holmyard, p. 43.) Carl Jung has also commented on the alchemical concern for creating a unification of the psychical and the physical, stating in his work, Mysterium Coniunctionis: An Inquiry Into The Separation and Synthesis of Psychic Opposites in Alchemy (Bollingen Series XX, Pantheon Books, 1963, pp. 537, 538, 544-545, 554), “undoubtedly the idea of the unus mundus is founded on the assumption that the multiplicity of the empirical world rests on an underlying unity, and that not two or more fundamentally different worlds exist side by side or are mingled with one another. Rather, everything, divided and different belongs to one and the same world, which is not the world of sense but a postulate whose probability is vouched for by the fact that until now no one has been able to discover a world in which the known laws of nature are invalid. . . . The intense emotion that is always associated with the vitality of an archetypal idea, conveys—even though only a minimum of rational understanding may be present—a premonitory experience of wholeness to which a subsequently differentiated understanding can add nothing essential, at least as regards the totality of the experience. . . . the alchemical opus was ... an individual undertaking on which the adept staked his whole soul for the transcendental purpose of producing a unity. It was a work of reconciliation between apparently incompatible opposites, which, characteristically, were understood not merely as the natural hostility of the physical elements but at the same time as a moral conflict. Since the object of this endeavor was seen outside as well as inside, as both physical and psychic, the work extended as it were through the whole of nature, and its goal consisted in a symbol which had an empirical and at the same time a transcendental aspect.”

16 Subsequent concern will be with the ideas and images reflected in Uelsmann’s work and not with the technical foundations of their form. All of the photographs illustrated are composite prints.

17 In a conversation with the author, 1967.

Accompanying the substantiation of archetypally motivated and monistically identified reality, wherein fractionalism is supplanted by polysynthesism, Uelsmann’s work provides trenchant evidence of a concern for configurative-imagistic continuity and relativity. This concern is overtly signified in Uelsmann’s photographs and appears to be grounded in a philosophy which has stemmed from limitedly recognized Platonic and Aristotelian ideas; 20 further, for the immediate purpose of determining foundations for his work and imagery, his belief in continuity and relativity indicates a participation in ideas which have been significantly heuristic in the development of photographic aesthetics.21 Uelsmann’s “Equivalent” of 1964 (figure 3) recommends itself as a definition of the semiotic imagery which may emerge from a concern for forms in continuum and subject to relativistic conjoination. The closed fist and anatomy of the nude in chiaroscuro impinge upon one another as astonishingly similar configurations; their masculine and feminine connotations existent as separate identities and, at the same time, affected by the enantiodromian interplay of comparative perceptions: the fist erotic, the body an expression of force; the nude becoming the hand, the hand the nude. Another extension of the concept of continuity and relativity effecting interpenetrative imagistic iconography is witnessed in an untitled photograph of 1963 (figure 4). Of this work Uelsmann has stated: “This was one of the earliest of the ‘room’ group. The intensification of the space . . . the shirt becoming something else. The shirt I just threw on the floor, without arranging it. It becomes a sort of symbol—of a man—and also a sort of shape growing out of her head.” 22 There is a mood of pervasive strangeness in this work, directly provoked by the juxtapositioning of familiar forms: in the foreground, the face of the photographer’s wife, Marilynn; on the floor above, the shirt hovering like a spectral creature; outside the room, the sentinel figure of a girl, her face and figure framed and “crosshaired” by the pane separations of the window through which she stares; and beyond, the pineapple palms and brush of the Florida landscape. Each separate unit would hardly appear unique in isolation, but in relationship, with the configuration of forms subject to imagistic continuity, each partakes of the symbolistic plenitude existent in the other. They combine to arrest our understanding of the significance of the bizarre and the lonely; they symbolize the curiosity of the secret encounter when privacy and contemplation are subject to furtive observation. Relatively, the observer of the photograph becomes, like the girl at the window, a participant in the mystery of observed utter isolation.23 A related symbolic interpenetration of forms appears in “Massacre of the Innocents” of 1964 (figure 5). The work conveys a specific sociological theme: a protest toward the failure of a Southeastern community to support the receipt of Federal funds benefiting underprivileged children. Parallels to the deprived children appear planally in the foreground of the photograph as a suite of paper dolls, valentine innocents paving the street, receiving the disdainful glance of a “negative” community resident walking by. Another figure, crone-like, stands at the corner of the U. S. Post Office of Lawtey, Florida, a flanking counterpoint to the American flag unfurled on the opposite side. Christmas garlands decorate the windows of the luminously desubstantiated architectural form. The “children” are like nostalgic reminiscences, discarded notional realities. The building, the persons, the flag, are positive reversal images suggesting fading postures of “lawabidingness,” apparitional inhabitants and objects occupying a very unreal world. The bitter impact of the photograph is not immediate; it can only be sensed in the recognition of the subject suggested by relationships and through the continuous repetition of the images affecting one another. The total effect documents a theme, doubly: the destruction of the human potential and the decorporealization of humane behaviour. At the same time the work reengages a persistent historical theme of inglorious human cruelty: the massacre of the innocents apparent in Biblical literature and in the art of such masters as Breughel and Raimondi.

18 The term is Lovejoy’s, one type of “metaphysical pathos.” Op. Cit.,

pp. 11,12.

19 Lovejoy: Ibid, pp. 12,13.

20 It would be absurd to think that this intimation could be exegetically defined in an article. At the risk of being too dependent upon a singularly provocative source, the following comments by Arthur 0. Lovejoy, may amplify the suggestion: “. . . it is in Aristotle that we find emerging another conception—that of continuity— which was destined to fuse with the Platonistic doctrine of the necessary ‘fullness’ of the world, and to be regarded as logically implied by it. . . . He is oftenest regarded, I suppose, as the great representative of a logic which rests upon the assumption of the

possibility of clear divisions and rigorous classification. . . . But this is only half the story about Aristotle; and it is questionable whether it is the more important half. For it is equally true that he first suggested the limitations and dangers of classification, and the non-conformity of nature to those sharp divisions which are so indispensable for language and so convenient for our ordinary mental operations. . . .” Lovejoy remarks that Aristotle’s concept of continuity encouraged diametrically opposed sorts of conscious or unconscious logic. He states: “There are not many differences in mental habit more significant than that between the habit of thinking in discrete, well-defined class-concepts and that of thinking in terms of continuity, of infinitely delicate shadings-off of everything into something else, of the overlapping of essences, so that the whole notion of species comes to seem an artifice of thought not truly applicable to the fluency, the, so to say, universal overlappingness of the real world.” Ibid, pp. 55, 57-58.

21 Uelsmann studied at the Rochester Institute of Technology and the University of Indiana. His former instructors and advisors included the photographers: Ralph Hattersley, Minor White, and Henry Holmes Smith. Particular ideas related to Uelsmann’s concern for continuity and relativity are evident in: Smith, Henry Holmes: Photography In Our Time: A Note on Some Prospects for the Seventh Decade (1961) and White, Minor: Equivalence: The Perennial Trend (1963), included in Lyons, Nathan: Photographers on Photography; op. cit., pp. 99-103, 168-175. It is equally interesting to note that Herbert J. Seligmann, in his document, Alfred Stieglitz Talking (Yale University Library, New Haven, 1966, pp. 17-18), reports that Stieglitz’s concept of equivalence emerged from his discovery of a law that everything is relative to the limits of the universe in any direction. These comments are made anecdotally, yet with significance nonetheless.

22 Kinzer, H. M.: op. cit., p. 180.

23 It is also evident that the observer becomes a participant responding to the relationships that the photographer defined in the combination of varied representations to create a total image. To this point, Sergei Eisenstein, in his essay “The Image in Process” of 1938, has defined aspects of imagistic development and participation in writing on the montage principle applicable to any form of art: “The juxtaposition of . . . partial details in a given montage construction calls to life and forces into the light that general quality in which each detail has participated and which binds together all the details into a whole, namely, into that generalized image, wherein the creator, followed by the spectator, experiences the theme. . . . Consequently, in the actual method of creating images, a work of art must reproduce that process whereby, in life itself, new images are built up in the human consciousness and feelings. . . . Montage, has a realistic significance when the separate pieces produce, in juxtaposition, the generality, the synthesis of one’s theme. . . . The strength of montage resides in this, that it includes in the creative process the emotions and mind of the spectator. . . . The image planned by the author has become flesh of the flesh of the spectator’s risen image. . . . Within me, as a spectator, this image is born and grown. Not only the author has created, but I also—the creating spectator—have participated. . . . the montage principle in films is only a sectional application of the montage principle in general, a principle which, if fully understood, passes far beyond the limits of splicing bits of film together.”—From The Film Sense (1938), translated from the Russian by Jay Leyda, New York, 1947. Copyright 1942 by Harcourt, Brace & World Inc.; included in The Modern Tradition: Backgrounds of Modern Literature, Edited by Richard Ellmann and Charles Feidelson, Jr.; Oxford University Press, New York, 1965, pp. 163, 164, 167, 168, 169,

Uelsmann’s view of reality includes a sensation for a world subject to change and transformation, a point of view toward rhythms of movement and plastic vibrations motivating forms. René Huyghe in Art and the Spirit of Man speaks of a new concept emergent in 20th century art, the concept of energy: “We find the same eagerness to capture the primordial impulse of life in terms of essential energy. . . . artists . . . seek to put themselves in tune with universal life, with the ‘cosmos,’ as they occasionally term it . . .” 24 Uelsmann, without denying the import of structure, shares this eagerness to sense the pulsation of experience, the primal energy of vital time and cosmic fluxion,25 not moments of change stabilized in the photographic fixity of an event, a person, place, or thing. His work suggests a concern for discovering what Erich Neumann phrased to be “a breakthrough into the realm of essence,” an attainment of “the image and likeness of a primal creative force, prior to the world and outside the world, which, though split from the very beginning into the polarity of nature and psyche, is in essence one undivided whole.” 26

Apparent in all, but specifically revealed in individual works, Uelsmann’s animated and autonomously dynamic world, including images constituted by forces, movement, and change, becomes vibrantly defined. Concrete definition is replaced by an intense activation of space and time, a “stilled” cinematic representationalism. In the work, “Introspection” of 1961 (figure 6), the flat, pine-scrub, goldenrod spiked, and bay-tree flora of the Northcentral Florida landscape is transformed into an environmental dream, wherein a somnolent sweater-girl walks, her image seen in the perspective of natural space and at the same time floating toward the frontal plane of the photograph in a facial montage permeating the landscape atmospherically, suggesting that she and her “spirit” and the world are one. In “Ritual Room” of 1965 (figure 7), symmetrical repetitions of mirror-imaged forms of bed sheets in disarray, rise like waves on tumultuous waters, creating a kinetic rorschach interior challenging the sinuate thrusts of glasspane scribbles and rampant interlaces of botanical forms seen without the window. A photograph created in 1965 (figure 8) features a flabellate and iconic palm frond, seemingly unfolding “wings,” its spears like tentacles fingering through the grass of a landscape including three solid earth forms aligned like incipient units of a dolmen—like ritual mounds behind the celebrant leaf—closured energy forms budding from the earth against a burst of variegated foliage. “The Return” of 1963 (figure 9) acquaints us with a human identification of Uelsmann’s concern for dynamism. In viewing the work, one might ask: what prodigal rushes toward the glowing and crumpled paper face, what rude hut receives the entry? What time defines the drama of return? What images of particularity and peculiarity, of specific time and place, are transformed in the focus of time in flux, the theme of movement from one point to another, the personification of figurative motion and transformation? Obviously, answers are discovered only in the empathie observation that what is witnessed is not a subject but the personified insignia of change.

24 Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, New York, 1962, p. 76.

25 Frank A. Doggett in his brilliant study, Stevens’ Poetry of Thought ((The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, Maryland, 1966, pp 67, 68) comments on the various and particular aspects of the flux that Wallace Stevens’ poetry offers, aspects which the present writer feels are remarkably similar to Uelsmann’s visually realized conceptions of change and fluxion: “Bergson’s duree, the stream of thought of William James, Whitehead's process, Santayana’s flux— these were terms familiar in the first third of our century to nonspecialists in philosophy and psychology like Wallace Stevens. The basic time image of these men is the archetypal image of flowing water.” One will recognize, upon familiarity with Uelsmann’s total oeuvre, the concentration upon the image of aqueous fluidity (see figure 12). Doggett continues: “This ancient image of time and change has almost lost its metaphoric character and seems now a simple observation of natural fact. In Heraclitus, it had been ‘fresh waters are ever flowing in upon you,’ and in our age James and Bergson and Santayana use the word flux as if it were a literal description rather than a comparison of a concept (time) to a physical fact. ... He (Stevens) approaches the image as though perceived by one person or as if in relation to an individual, or as the flux of life, of common experience, or as the cosmic flux of life, matter, all.”

26 Eranos Yearbooks, Ed. by Joseph Campbell, Bollingen Series XXX.3, Pantheon Books, New York, 1957, p. 17. In this same essay Neumann suggests that “An animistic, pantheistic sense of a world animated by the archetypes is revealed in the autonomous dynamic of natural form, . . . the autonomous dynamic creates psychic landscapes whose mood, emotion, color—. . . —are the authentic expression of the powers. These powers everywhere, in wind and cube, in the ugly and absurd as well as in stone or stream— and ultimately in the human as well—are manifested as movement, never as given and fixed things.” (p. 33). Lancelot Law Whyte,

Reality as process preconsciously structured by archetypal provocations; a unitary reality which makes the mundane facts of the usual pale before the possible; reality as a philosophy which sees in man and things the image of continual change and transformation: for Uelsmann these are awarenesses to be defined in the reality of the photograph. His work conjoins with other significant reactions toward the limitations of rationalism which dawned from Descartes’ dreams of St. Martin’s Eve on November 10th in 1619, dreams which apparently codified for Western man a felt, if not actual, separation between mind and matter, a split between psyche and world. Fortunately, Uelsmann, among other major creative persons, has refused this feeling, cultivating an ability to represent the uniqueness of the actual and the potential of the actual for becoming more than it specifically seems.

writing of discoverers of the unconscious before 1730, mentions “the Cambridge divine, philosopher, and student of science,” Ralph Cudworth (1617-1688), and his “outlook . . . based on a ‘plastic nature,’ vitalized by ‘plastic energy’ also, Shaftesbury (1671-1713), who interpreted “the divine spirit of the world as a plastic force, or as he called it a forming power pervading everything: matter, life, and mind." See The Unconscious Before Freud, op. cit. pp. 88, 89, 91.

3

Symbolic modes defining qualities of Jerry Uelsmann’s composite photographs reveal notable recurrences, rather than lineal manifestations, of the attention of his creative consciousness. His images are increasingly subtle and complex reenactments of veridical intuitions and observations cumulatively attractive to his eye and mind. Viewed as such, his art develops through a process of variations in symbolic reengagement. His works are not creations defining the positivists’ reality subject to “ticktock” time; rather, they are corroborations of a cyclical search for the eternalness of an archetypal and unitary reality, multifariously intimating the time of clocklessness —mythical and spiritual time—and existent as varying expressions of invariable provocations.27 Thus, while his motivating sources are felt to be constant—as constant as the instincts and as long as psyche and flesh, spirit and matter remain viable—Uelsmann’s modes of symbolic representation serve as ways to create identification of this unitary reality. These modes are marked by incredible variation. This point would be awesomely evident if one were to establish an inclusive familiarity with the composite photographs Uelsmann has created in little less than a decade—close to two hundred and fifty major exhibition works, not to mention innumerable experimental forms never publicly shown. While retaining an impressive relational integrity, his photographs present a visualperceptual range that is extraordinary, considering the complexity of the forms, and an astonishing variety or potential for expansion, considering the frequently stated though obviously debatable belief that particular techniques and latitudes of representation intrinsic to such techniques are mutually definitive and limiting.

27 Rich sources which may amplify this opinion are: Mircea Eliade’s work, Cosmos and History: The Myth of the Eternal Return (Harper Torchbooks/The Cloister Library, Harper & Brothers, New York, N. Y., 1959); Man and Time: Papers from the Eranos Yearbooks (Bollingen Series XXX.3, Pantheon Books, Inc., New York, N.Y., 1957), particularly the papers by Erich Neumann (Art and Time, 1951), Henri-Charles Puech (Gnosis and Time, 1951), Giles Quispel (Time and History in Patristic Christianity, 1951), and Adolf Portmann (Time in the Life of the Organism, 1951). Uelsmann, with characteristic wit, wrote to the author in a letter of July 8, 1967: “. . . I think I’ve been making the ‘stills’ for God’s home movies . . .” Curiously, this aside is delightfully suggestive of his concern for the numinosity attendent to archetypal recognitions. Erich Neumann amplifies the thought in his statement: “Thus from the very outset man is a creator of symbols; he constructs his characteristic spiritual-psychic world from the symbols in which he speaks and thinks of the world around him, but also from the forms and images which his numinous experience arouses in him. . . . the creative struggle with the numinosum has fallen to the lot of the individual, and an essential arena of this struggle is art, in which the relation of the creative individual to the numinosum takes form.” (from, Art and Time, ibid, pp. 5, 13.) The word numinous, beyond its derivation from the Latin word numen, meaning god, is profoundly defined in Rudolf Otto’s classic work, The Idea of The Holy (A Galaxy Book, Oxford University Press, New York, N. Y., 1958, particularly Chapter IX,3.: Means by which the Numinous is expressed in Art, pp. 65-71, and Appendix V: The Supra-Personal in the Numinous, pp. 197-203.) Otto remarks :“. . . all that we call person and personal, indeed all that we can know or name in ourselves at all, is but one element is the whole. Beneath it lies, even in us, that ‘wholly other,’ whose profundities, impenetrable to any concept, can yet be grasped in the numinous self-feeling by one who has experience of the deeper life.” (p. 203). Uelsmann’s concern for the uncanny, mythical, and the numinous in his photographs has often earned for the works the accolade or antagonism of the term “mystical.” In any case or event, it is the author’s opinion that his forms definitely burst the bounds of the simply personal, the confines of traditional imagistic canons, and the closed consciousness of the intellectually determinative artistic.

In view of the diversity of his forms, articulating the range of Uelsmann’s symbolic modes must be less than comprehensive; however, an interpretive overview leaning directly on Juan Eduardo Cirlot’s definition of four functions of symbolic syntax concluding the illuminative introduction to his Diccionario De Símbolos Tradicionales,28 will, with trust, extend the response to the photographer’s field of symbolic action.

The photograph, “Yesterday’s Child” of 1966 (figure 10) introduces the first mode of symbolic syntax which Cirlot calls the successive manner involving “one symbol being placed alongside another; their meanings, however, do not combine and are not even interrelated.” It is possible that meanings may be evoked by the serially distributed forms—the monumental face, the pendant pillow gently goaded by the doorknob, the shirt hanging like a dark waterfall interrupting the starkly vertical slice of the door —meanings that might be associated with design relationships or sensed fancies of sexuality, implied by the series in conjunction. It is unlikely that any metaphorical interpretation would enhance the basic symbolic function of the work. In numerous composite photographs Uelsmann employs objects and figures whose individual imagistic plenitude is purposely defined within limits just prior to interpenetration with companionate forms. In this ordering process of selection and composition the forms become tensional units, individually defined as a series and independently creating imagistic suspense as a result of their inhibited juxtapositioning. Numerous works similar

28 Translated from the Spanish as A Dictionary of Symbols by Jack Sage (Foreword by Herbert Read); Philosophical Library, New York, N. Y., copyright, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. 1962, published by Philosophical Library, Inc., 1962. Cirlot states: “Symbolic syntax in respect of the relationship between its individual elements, may function in four different ways: (a) the successive manner ... ; (b) the progressive manner . . . ; (c) the composite manner ... ; (d) the dramatic manner . . .” (p. liii) Cirlot’s explicit definition of each manner will be documented wherever apparent in the remaining context of this paper. It is important to realize that Cirlot’s opinion is that “Symbols, in whatever form they may appear, are not usually isolated; they appear in clusters, giving rise to symbolic compositions which may be evolved in time (as in the case of story-telling), in space (works of art, emblems, graphic designs), or in both space and time (dreams, drama). . . . But we must also recall that the Scylla and Charybdis of symbolism are (firstly) devitalization through allegorical over-simplification, and (secondly) ambiguity arising from exaggeration of either its meaning or its ultimate implications; for in truth, its deepest meaning is unequivocal since, in the infinite, the apparent diversity of meaning merges into Oneness.” (pp. lii, liii) It should be clear by implication that Cirlot’s use of the terms is most inclusive and that his views on symbolic interpretation are sensitive to incautious approaches. His use of terms and attendant amplifications are not necessarily pointed to others for critical use; however, his four functions of symbolic syntax are so insightfully related to the symbolic encounter in all the arts and in the history of ideas, that the present author chooses to liberally employ Cirlot’s symbolic categories.

to the one at hand, in terms of symbolic function, suggest the possibility of unification without resolving the image of the reality itself. Using the successive manner of symbolic syntax, Uelsmann prompts the observer into a state of expectancy, into a desire to witness relationships, and, at the same time, clearly recommends to the eye, the nature of the human tendency to differentiate. He clearly defines the prelude to enriched symbolic union, approaching the borders of polysynthesis while keeping the quality of differences intact. Both fact and possibility contribute to the dynamics of this work and to others similarly formed in the successive manner.

Comparable to the compositional order of “Yesterday’s Child” is “Room Number 4” of 1963 (figure 11), a work indicative of the progressive manner in which units represent different stages in the symbolic process. Each configured unit is an expectant “presence”, awaiting symbolic amalgamation with the others, or, in a fundamental sense, appearing to affect parallel relationships as a result of a collective occupancy of continuous space. In “Room Number 4,” a chthonic natural form—pod and husk— grown from the energy of Nature is recorded as a vegetational paradigm for male and female union. The motif is a visual metaphor for vital procreative powers and cooperating forces of the natural and human world; as such, it emanates a common and cumulative symbolic rhythm which spreads its identity to the other configurations. The female figure in silhouette strikes a passive pose, becoming a vague form intensified by the illuminated backdrop of wild Nature, and awaiting clear emergence, identification, and definition. The male image, an energetic torso cropped in the natural stance of classical contrapposto, seems to share with the girl a dramatic destiny which may include, but quite transcend, the connotations of the signally insistent natural form on the left. The two figures appear to be candidates for an archetypal enactment, a celebrative drama, which will include the recognition of opposites and culminate in their union. The male stands with assurance and certainty, as an ephebe and man, in the dark context of isolation; the female appears as a shaped possibility, a shadowy spirit figure, just come from earth and nature and light. The pod-husk form suggests a physical encounter, yet this stage of relationship has already been fulfilled by its own presence. Following the progression of symbolic possibilities, intuitively prompted by the images within the work, one will inevitably sense a hint toward the recognition of a psychical, rather than physical, conjunction; a coniunctio of masculine consciousness with incipient components of the feminine unconscious, the male and female principles—in the imagery of the photograph only implied, but symbolically promised through contemplation. The progressions of symbolic imagery in the work are remarkably reminiscent of familiar archetypal forms. For example, the pod and husk combination is comparable to the lingam and yoni motif in Indian art, a composite form in which the lingam or phallus, symbolizes male creative power, and the yonl, its counterpart—often forming the base for the lingam and on occasion individually apparent as a “convex, swelled-out symbol marked by a furrow,” 29—imagistically expresses female creative energy. The two forms combine to represent the “creative union that procreates and sustains the life of the universe.” 30 The description of the symbolic potential affected by the presence of the girl and boy in the photograph, is ultimately realized in a comparative image from Cambodia, a fourteenth-century stone sculpture: “Lingam Revealing The Goddess.” (figure 11a). Heinrich Zimmer has written of this almost incredible image: “Shiva and the Goddess represent the polar aspects of the one essence and therefore cannot be at variance: she expresses his secret nature and unfolds his character . . . the symbol of the lingam opens up at the four sides and discloses, among other figures representative of its power, the Goddess herself . . . here the Goddess has ten arms and five heads ... is the essence, the creative energy, the shakti, of the phallic pillar.” 31 As creative energy the goddess represents an aspect of the total psychic identity, the archetype of the perennial feminine principle of earth, matter, and the inspiring unconscious viewed from the referential standpoint of mythic identification and twentieth-century active ego consciousness with its characteristic male symbolisms. With certainty, Uelsmann has approached an intimation of this archetypal level in the progressive symbolisms of “Room Number 4.”

Cirlot writes of a mode of symbolic syntax “in which the proximity of the symbols brings about change and creates complex meanings: a synthesis, that is, and not merely a mixture of their meanings.” He refers to these functions as occurring in the composite manner. The representations of a wind-felled tree bearing unexpected foliage and a recumbent figure of a beautiful woman gently commingled with scintillating corrugations of an open field transformed to rippling water, coalesce in an untitled photograph of 1966 (figure 12). This tranquil and rhythmic form is exemplary of composite symbolic synthesis.

An evidence of Uelsmann’s extension of symbolism transcending the technical and iconographical intentions in the early tradition of combination printing, is discovered in a comparison between the present work and H. P. Robinson’s “The Lady of Shalott” created in 1861 (figure 12a). Helmut Gernsheim, writing of this work made up from two negatives, states: “ The Lady of Shalott’ . . .

29 Zimmer, Heinrich: Myths and Symbols In Indian Art and Civilization (Edited by Joseph Campbell), Harper Torchbooks, The Bollingen Library, Harper & Row Publishers, New York, N. Y., copyright 1946 by Bollingen Foundation, Inc., first Harper Torchbook edition published 1962, p. 138 (the words refer to a representation of the yoni held in the left hand of the goddess Shakti, in a Bengalese relief of the tenth-century A.D., depicting Shiva with his consort; see Figure 34 accompanying Zimmer’s text).

30 Zimmer, Heinrich: ibid, p. 127.

31 Zimmer, Heinrich: ibid, p. 199.

was a bold attempt to illustrate Tennyson’s romantic poem . . . while this deliberately artificial picture somehow succeeds in conveying something of the romantic spirit of Tennyson’s poem, Robinson’s favourite rustic compositions . . . strive after naturalism and fail completely.” 32 Such criticism is not at all disagreeable, for Robinson did indeed attempt to extend the limits of imaginative naturalism without success. He failed because his work remained too entrenched within the bounds of a limited perception of natural truth. Uelsmann’s image is neither inhibited naturalism nor a poetic interpretation of a world obvious to the eye. His form is a fact, truly an event and an objective identification of relationships which are permeational and literal to an unlimiting sensibility. The presence of the total image is in the service of reality rather than magic. If one can accept the amalgamation as credible, a synthesis of complex meanings will ensue as a consequence of belief.

Plastically, the work is a masterpiece of pervasive structural confluences: note the tremulous stream-patterns of water wrinkled by darts of wind repeated in the fall of folds and draped undulations of the dress; the contours of negative shapes defined by the lateral trunk and leafless branches of the tree parallel to the bounding line of the horizon, contours befitting identical fusion with the upper configured edge of the figure and the internal linearities of its gown; the pneumatic balloon of central foliation in the tree echoing the vibrational and watermoon globousness of the reflection in the foreground. Each relationship is a denial of separateness and isolated identification, each interrelation configures a gestalt emanating profound symbolic implications. Sensing the extraordinary content implications of this form will be difficult unless one is willing to sympathize with deeper promptings of archetypal images; in this case, with the elementary character of the Feminine and its identification in the reposed woman, earth and vegetation, water, and the quiet energy of nature in transformation. Erich Neumann, in The Great Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype, evokes entrances to this sympathy: “The Great Goddess is the flowing unity of subterranean and celestial primordial water ... To her belong all waters, streams, fountains, ponds, and springs . . .”33 “The Great Earth Mother who brings forth all life from herself is eminently the mother of all vegetation. . . 34 “Because the earth, as creative as-

pect of the Feminine, rules over vegetative life, it holds the secret of the deeper and original form of ‘conception and generation’ upon which all animal life is based. For this reason the highest and most essential mysteries of the Feminine are symbolized by the earth and its transformation.” 35 Considering the integrations cultivated by Uelsmann’s sensitivity, it is likely that what we see in the photograph is not only quantitative interpenetration—of tree and woman, water, earth, and sky—but a qualitative transformation of spirit in his recognition of the signals of the Archetypal Feminine—in the creation of a setting for his “soul image,” his anima, his own “soulfulness, . . . formed in part by the male’s personal as well as archetypal experience of the Feminine. . . .” 36

32 Gernsheim, Helmut and Alison: The History of Photography, op. cit.,

pp.180-181.

33 Bollingen Series XLVII, Pantheon Books, New York, New York,

1955, p. 222.

34 Ibid, p. 48.

35 Ibid, p. 51.

To approach a unitary reality is a major intentional effort and most creative individuals are not equal to the task. Courageously, Uelsmann seeks to define a complete evocation of existence as one searching for a confirmation of self and symbol in the art of photography. Toward an integration of concern, certain series of photographs monumentalize the last mode of symbolic syntax, the dramatic manner. In this mode, grouped identifications of a grand symbol occur. All singular images apparent as separate documents of a unique creative consciousness cohere within an archetypal context. The photographs which follow express themselves in the archetypal context which has been intimated by the previously discussed photograph: the Archetypal Feminine.*7 Whether this context includes symbolic identifications of the Feminine as earth, goddess, mother, inspiratrice, anima, the revealing unconscious in man, spirit world, unifying mandala, or the image of the ritual hierosgamos, or union of male and female principles, none—individually—will encompass the totality of imagistic affect serving to define a grand symbol. Fortunately, this end must be recognized by the observer who contemplates the subsequent composite photographs as collective identifications of a meaning which must include one’s own identity as part of the necessary experience of the symbolic process and, ultimately, of magnificent recognition.

In five photographs (Figures 13 through 17) the mystery of the Archetypal Feminine is revealed with remarkable variation. Essentially, the five works evoke a series of successive revelations of the image as symbolic of the association of woman with the natural world and of the Feminine presence as a numinous reality. An untitled work of 1965 (figure 13) represents the typical ambivalence of an archetypal image, the elementary positive and negative characteristics of its presence apparent in symbolic form. A sculptured goddess, an exquisite riddle, blooms amidst leaves; a Kore figure, recently burst from bonds of underworld concealment and cavernous darkness reveals herself above the terrifying yawn of the claw-teeth petals below her rising form. Above, a mythical anima figure, an object imbued with the presence of the transformative feminine spirit; below, a vestigial sign of her ancient mother: the maw of the earth, “the abyss of hell, the dark hold of the depths, the devouring womb of the grave and of death, of darkness without light, of nothingness.” 38 A composite image of biomorphic and suprahuman identity, associating nature and earth with the Feminine, is evident in a combination print of 1963 (figure 14). The linear criss-crosses of weeds and grasses and their flecked interstices configure a woman’s face, implying an identification of bush and plant—in fact, all vegetative life—with nature as Mother, as a fertile presence preeminently the source of all natural fruition and decay. Strikingly parallel to this work and its image is a detail from an eleventh century manuscript painting in an Exultet Roll illuminated at the Abbey of Monte Cassino, now in the British Museum (figure 14a). Earth is shown as a woman suckling monsters, her arms upraised in a gesture of epiphany, her body the mound of earth itself with several representations of its creature inhabitants and organic forms. Another variant in Uelsmann’s concentration on the content of the Archetypal Feminine becomes manifest in “Myth of the Tree,” a composite work of 1962 (figure 15). Though his titles for works are developed for cataloguing purposes, there is an intuitive amplification of content in his naming of this work. The face of a woman appears as the foundation for the soaring thrust of a tree. Neumann commenting on the vegetative symbolism of the tree states that fruit-bearing trees are to be identified under the aegis of the Archetypal Feminine, serving as representations of the nourishing, containing, and transforming aspects of the female nature of the tree. He also reminds us, however, that the tree may symbolize the “earth phallus, the male principle jutting out of the earth, in which the procreative character outweighs that of sheltering and containing. This applies particularly to such trees as the cypress, which, in contrast to the feminine forms of the fruit trees and leafy trees, are phallic in the accentuation of their trunks.” 39 Remembering the image evoked by the vegetative form in “Room Number 4” (figure 11), one may discover that here too is an image of united masculine and feminine principles; however, it is probable that Uelsmann’s intuition, from which this photographic image arose, conceived of the mask-like face to be an image of the Feminine as primal energy, a prelude to his sensitivity defining the archetypal image of the Feminine as earth, since it includes the identical facial form of the later print of 1963 (figure 14). That the image in “Myth of the Tree” is not simply a personal notion, but a transpersonal recognition, is verified relationally in the tree symbolism of an alchemical illustration (figure 15a) wherein a figure represents the female tree of destiny and bearer of images of transformation.40 A further manifestation of the earth archetype awakened by the experience of the Archetypal Feminine occurs in a print of 1966 (figure 16) defining the uppermost figure of an empty-eyed introspective woman encapsulated under the seemingly petrified arch of a triangulated mirror-imaged tree trunk surrounded by jutting boulders. The image shares the iconological import of the Great Goddess abiding within the subterranean core of geological nature and pictured with penetrative mystery in Leonardo da Vinci’s painting, “The Virgin of the Rocks,” (figure 16a). Neumann in his essay, “Leonardo and the Mother Archetype”41 recognized an aspect of the Zeitgeist which motivated, archetypally, the creation of Leonardo’s work: “Whereas the Middle Ages—and particularly the Gothic period— were dominated by the archetype of the Heavenly Father, the development begun in the Renaissance was based on a revival of the feminine earth archetype. In the course of the last centuries it has led to a revolution of mankind ‘from below,’ taking hold of every layer of Western existence. . . . This striking of roots made possible the discovery of the body and natural science, and also of the soul and the unconscious; but underlying all this was the ‘materialistic’ foundation of human existence, which as nature and earth became the foundation of our view of the world as manifested in astronomy and geology, physics and chemistry, biology, sociology, and psychology.” 42 Of the imagery in the painting, Neumann continues: “This madonna is unique. In no other work of art has the secret that light is born of darkness, and that the Spirit Mother of the child savior is one with the sheltering infiniteness of earthly nature, been manifested so eloquently. The triangle, with its base on the earth, which determines the structure of the picture, is an old feminine symbol, the Pythagorean sign of wisdom and space.” 43 Uelsmann’s “goddess” is a sister to the Virgin, an iconic presence rising from the base of the photographic form, entering the chambered whiteness of an ascendant spatial arrow touching the tip of a dark heart-like shape growing upward and linked serially to smaller darts and angles pointing toward the minuscule crevice opening to the sky. The image of woman as a numinous, transpersonal presence is dramatized in “Quest of Continual Becoming” (figure 17). Seated like an enthroned priestess in the corner of a symmetrically invented room appears an essentially static image of the Feminine, disturbed into mobility only by the suggested closing and unfolding of her quaternate arms. Similar to a neolithic image of a primordial goddess (figure 17a), the hieratic impersonalism of her presence is astonishing as an image of beckoning archetypal power. Both photograph and sculpture relate to the image of the seated Great Mother, “the original form of the ‘enthroned Goddess,’ and also of the throne itself. ... As mother and earth, the Great Mother is the ‘throne’ pure and simple, . . .”44 originally symbolized by the mountain, “an immobile and sedentary symbol that visibly rules over the land. First it was the Mountain Mother, a numinous godhead; later it became the seat and the throne of the visible or invisible numen; still later, the ‘empty throne,’ on which the godhead ‘descends.’ ”45 In Uelsmann’s image the gesturing woman awaits becoming, to be possessed by a recognition of her presence as an image of fascinating unconscious forces.

36 Ibid, p. 33. 37 The writer is well aware of the difficulty of this conception and also of the problem of ensuring that it may be believed, let alone be considered as a credible possiblity. Nonetheless, he trusts that it will be recognized by some that archetypes cannot be advantaged by abstract conceptions of their reality, for archetypal images are not what is written about them, but what they are in experience and expression. Uelsmann’s work need not depend upon the support of “explanations,” nor should it be misconstrued by anyone that what he creates is felt by the author only to be significant in that it can be approached referentially, rather than experienced as forms, as works of art. It is guaranteed that what he creates contains and may prompt a variable recognition of content as flexible as that posited in every individual who “sees” his work.

38 Neumann, Erich: The Great Mother, op. cit. p. 149.

39 Neumann: ibid, p. 49.

40 For an analysis of this image and referential notes see Neumann: ibid, p. 248.

41 One of four essays in Art and the Creative Unconscious, Bollingen Series LXI, Pantheon Books, New York, New York, 1959.

42 Ibid, p. 32.

43 Ibid, p. 35.

For the masculine consciousness the possession of feminine unconscious forces is a major opus in the process of becoming a complete individual, a total human being. When this conjunction within the human personality takes place and images of its process are projected into art, the symbol of the hierosgamos, the sacred or spiritual marriage of archetypal forms evoking a unified reality is configured. The personification of the feminine nature of a man’s unconscious—as woman, matter, muse, and earth; “as a force that sets him in motion and impels him toward change . . . the active inspiration of the Feminine presiding over the birth of the new” 46; as the mediating function of the anima image which remains “in place between individual consciousness and the collective unconscious,”47 the source of archetypal motivations— becomes the substance for a grand symbolism and the testament to a deeply personal creative process. Uelsmann engages both the personal reality and the externalized theme in a series of works related to previous forms developed in the dramatic manner. “Celebration of Life” of 1965 (figure 18) iconographically suggests the image of woman risen from the undifferentiated matter of an earthy canyon. Confident in her emergence beneath a hovering foliate cloud which recalls the atmospheric representations of the procreative classical Gods—for example, Zeus, as a cloud emitting a shower of gold (figure 18a)—the woman as a symbol of the unconscious awaits conjunction with the pneumatic masculine spirit connoted by the foliate orb, a visual metaphor for consciousness in the male. René Magritte’s surreal “Castle of the Pyrenees”, 1955 (figure 19a) provided the external source for the imagery of Uelsmann’s “Magritte’s Touchstone” of 1965 (figure 19). Magritte’s lapping oceanic waters have been transformed to earth and earth’s personification in the reappearance of the sleeping woman; the floating rock in the painting becomes a massive boulder above landscape and woman in Uelsmann’s photographic form, an intimation of the Self attendant to the revelation of the Archetypal Feminine. An untitled work of 1966 (figure 20) recapitulates the image of woman as terrestrial creature and mediatress of revelation. The looming left hand of the reclining woman carries a negative reversal image of a masculine figure, an emergent identity of the “other half” of the total being revealed from the unconscious. S. Giedion in The Eternal Present: The Beginnings of Art,48 suggests amplifications related to this image, in writing: “Bachofen considered the left hand to be ‘the symbol of the maternal aspect of matter.’ In support of this he cited Pliny, who linked the left side of the human body with the female principle. In suggesting relationship with the Mother-Goddess, Bachofen referred to a passage in Apuleius recounting how, in the Egyptian procession of Isis, ‘the Egyptian Great Mother,’ the priests carried a large representation of a left hand . . . That Bachofen was justified in his views on the significance of right and left hands—which he stressed frequently—is supported by recent researches. ‘It goes beyond the realm of a single world creation myth to an almost universal conception of mankind that the right side is regarded as male and the left as female’ (Baumann).” 49 Uelsmann’s figure occurs in the lineage of this grand symbolic implication—the left hand associated with the revelational anima figure and also with the unconscious which brings to bear the dark twin to one’s conscious identity and the coordinate awareness of one’s very soul. Uelsmann’s imagistic effort to portray his intensity for unifying masculine and feminine principles, to seek a conjunctive possibility for awareness of totality, appeared as early as 1961 in his photographs, “On Marriage” (figure 21) and “Symbolic Mutation” (figure 22). In both, the search for masculine-feminine union is dramatically symbolized: the hand with ringed finger sinking into the earth, a ritualistic image of mystical union; the fist seemingly grasping the elusive female face, a documentation of the urgency to arrest the anima presence as substance and as form. Culminating imagistic expressions of this search for a union of opposites appear in two untitled works of 1966. In a complex landscape (figure 23), man and woman stand beneath a “treetemple” arch, awaiting the eminent drama of conjunction. Between the figures, defined within the inverted pyramid of light, a sign of union, a branch-fragment linkage, informs the potential affect of the scene. Dominant in the foreground is a rocklike mandala or magic circle, expanding the projected promise of equilibrium and totality. Similar symbolistic affect occurs in a sixteenth century manuscript illustration, “Alchemical Vessel with Tree” (figure 23a). Illustrated is an aspect of the mystery of “the transformative process rising from the vessel . . . represented by the pillar-tree, round which is twined the double snake of the opposites that are to be united.”50 The tree,

44 Neumann, Erich: The Great Mother, op. cit., p. 98.

45 Ibid, p. 99.

46 Ibid, p. 32.

47 Jung, C. G.: from Unpublished Seminar Notes. “Vision” I, p. 116, in Memories, Dreams, Reflections; Vintage Books, New York, New York, 1965, p. 380.

48 Bollingen Series XXXIV.6., Pantheon Books, New York, New York, 1962.

49 Ibid, pp. 109-110.

50 See Neumann, Erich: The Great Mother, op. cit., p. 328.

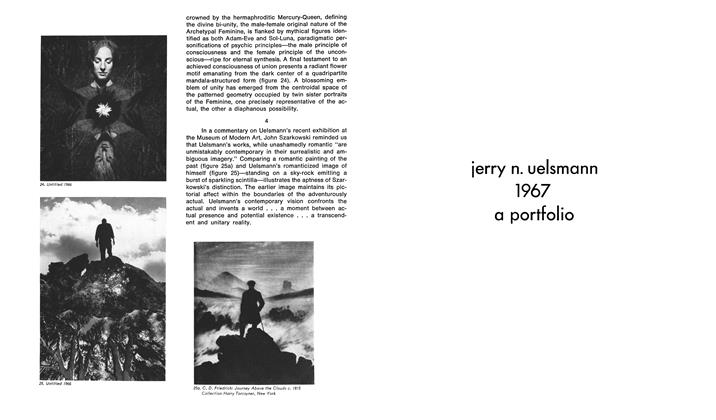

crowned by the hermaphroditic Mercury-Queen, defining the divine bi-unity, the male-female original nature of the Archetypal Feminine, is flanked by mythical figures identified as both Adam-Eve and Sol-Luna, paradigmatic personifications of psychic principles—the male principle of consciousness and the female principle of the unconscious—ripe for eternal synthesis. A final testament to an achieved consciousness of union presents a radiant flower motif emanating from the dark center of a quadripartite mandala-structured form (figure 24). A blossoming emblem of unity has emerged from the centroidal space of the patterned geometry occupied by twin sister portraits of the Feminine, one precisely representative of the actual, the other a diaphanous possibility.

4

In a commentary on Uelsmann’s recent exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, John Szarkowski reminded us that Uelsmann’s works, while unashamedly romantic “are unmistakably contemporary in their surrealistic and ambiguous imagery.” Comparing a romantic painting of the past (figure 25a) and Uelsmann’s romanticized image of himself (figure 25)—standing on a sky-rock emitting a burst of sparkling scintilla—illustrates the aptness of Szarkowski’s distinction. The earlier image maintains its pictorial affect within the boundaries of the adventurously actual. Uelsmann’s contemporary vision confronts the actual and invents a world ... a moment between actual presence and potential existence ... a transcendent and unitary reality.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Leslie Krims

Fall 1967 By Peter C. Bunnell -

A Meeting Of The Portland Interim Workshop

Fall 1967 -

Jerry N. Uelsmann: 1967, A Portfolio

Fall 1967 -

Comment And Review

Comment And ReviewPhotography And The Mass Media

Fall 1967 By John Szarkowski -

Comment And Review