He had made the woodpile himself so I have tried to immortalize him with it.

Work is love made visible

Kahlil Gibran

"One must be able to gain an understanding at short notice and close range, of the beauties of character, intellect and spirit so as to be able to draw out the best qualities and make them show in the outer aspect of the sitter. To do this one must not have a too-pronounced notion of what constitutes beauty in the external, and above all not worship it. To worship beauty for its own sake is narrow and one surely cannot derive from it that aesthetic pleasure which comes from finding beauty in the commonest things.”

Imogen Cunningham Wilson’s Photographic Magazine, March, 1914

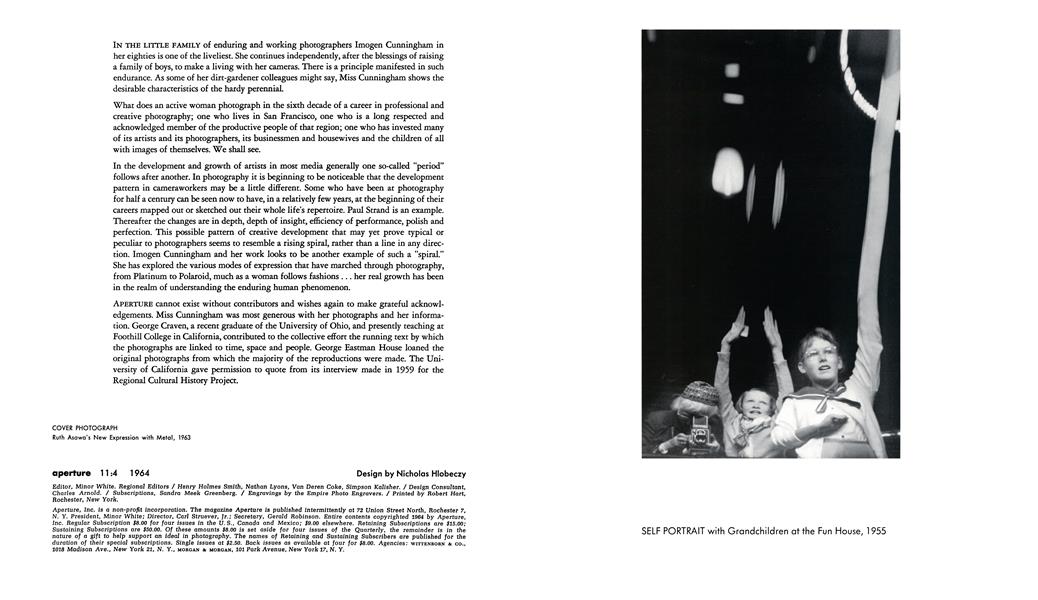

THE WORK OF IMOGEN CUNNINGHAM spans nearly half the history of photography and encompasses all of its traditional modes of expression. While her earliest images are in the mainstream of pictorialism, her later ones in the vein of the documentarian, much of her work, like the best in any medium, defies classification. From the beginning sixty-three years ago she has never hesitated to experiment; through all her efforts, however, runs the central idea that photography, as all art, must in some way be concerned with life. And in the photographs of Imogen Cunningham, the pulse of life is vibrant and sure.

In all her thousands of photographs and all her reflections of various periods she pointedly refuses to be put into a niche. "I’ve tried my best,” she has often remarked, "to sell people on the idea that I photograph anything that can be exposed to light.” Her versatility spins out of a hard core of sensitivity to the human spirit. Her photographs, as she herself, vitalizes us.

THE OLDEST CHILD OF SIX by her widowed father’s second wife, Imogen Cunningham was born in 1883 at Portland, Oregon. In primitive Seattle, where she was raised and started to photograph in 1901, she still remembers seeing bear tracks in the woods on her way to school. Her father, vegetarian, a believer in communal life, a road mender, farmer, well read in many fields including Theosophy, was understanding and patient with her early interest in drawing and painting. He arranged for his favorite, and erratic, daughter to study art privately, since there was no art instruction in the public schools, on week ends and summers. She was always on her own, interested in something or other that her family was not. One day in 1900 she saw the photographs of Gertrude Käsebier, later a member of the Photo-Secession in New York, reproduced in The Craftsman. "If I could only be that good!” she thought and set about persuading her father to build a darkroom in the woodshed. He did during 1901.

At the University of Washington, which had no art or art history courses at the time, she majored in Chemistry. She learned to make lantern slides for Botany. After college she worked in the studio of Edward S. Curtis, famed pictorial photographer of Indians. "The man who influenced my life at that time was A. F. Muhr, who has never been heard of since. He was the operator of the Curtis establishment and he was a gentleman from way back, also a fine technician. He really gave me the run of the place, and I learned the platinum printing process from the gal who did it—I have forgotten her name. She married and I was given the job after working there five months.” She remained for two years.

GERMANY AND RETURN

In 1909 she went to Dresden, Germany on a Scholarship of $500.00 provided by the national organization of Pi Beta Phi to the Technische Hochschule and continued her study of physical chemistry as related to photography. "I did some experiments on the amount of seeing that can be done with green light. Panchromatic film was just then being investigated. I also made a photographic printing paper in imitation of platinum but using a much cheaper salt, that of Lead. The article I wrote on this was published in a German magazine and paid for. It was later translated by the English and published without my permission, though my name was attached.” The spare time was spent at museums, theatre, opera and a little nearby traveling during vacations. The photographing was mainly portraits.

"After Germany, and I think even before, I knew that I was more interested in the visual and what one can do with photography than in the scientific.”

She visited London on the way home photographing some of the sights. There is a handsome Platinum print of the fountain in Trafalgar Square, dated 1910, in the extensive collection of her work at Eastman House. She stopped to visit Alvin Langdon Coburn, another member of the Photo-Secession, who had just moved to England. In a letter dated 1964 she wrote, "I met Coburn at his studio .. . my impression of him then was that he was a very handsome young man with a red beard ( about the color of my own hair ). He had a very watchful mother who, when Alvin was not in the room, told me that I could never become as good a photographer as Alvin. But he was not at all like that.”

In New York she met Alfred Stieglitz, the motivator of the Photo-Secession at the Gallery called 291. "Of course I was greatly impressed and rather afraid of him. I did not express myself in any way that anyone could possibly remember. At the time I felt that he was very sharp and not very chummy. I looked up Gertrude Käsebier. She was most cordial. She was working with students on platinum printing and had one eye bandaged from an infection caused by the platinum. As long as I worked with platinum I managed to avoid this, though it was quite common.”

Stieglitz, when I photographed him in An American Place with his own camera he was very willing. I brought my own holders for it. The camera was so old and wobbly that I had to wait until it settled down, after I put the holder in. Also I had never used a bulb release, so he practiced me with it. I had no meter and just held the bulb as long as I thought he was “holding." It worked, seven negatives, nothing moved.

Letter 1964

SEATTLE

Thus prepared, Miss Cunningham returned to Seattle without wishing to work elsewhere and opened a portrait studio in an attractive little cottage on "First Hill.” "Mrs. Elizabeth Champney who was already what I thought was an 'old lady’ was my first customer. She had written Vassar Girls Abroad, a book I never got through. Though flash powder in a pan was in vogue I preferred the naturalistic. I was not greedy and I had enough portrait work of both children and adults from the very beginning to pay my debts from the European trip and eat, so I started 'fooling around’ with friends as models. From this period the only things that I still like are 'The Wood Beyond the World’ suggested by a William Morris story of that title—a man and woman in flowing drapes on a wooded path. ( Eastman House has a splendid print of it. ) There are others of various people both naked and draped in the woods or standing in a pool of water.”

These were busy years, she joined the Pictorial Photographers of America, the Seattle Fine Arts Society, became friends with John Paul Edwards who was the motivator of an organization in California whose members sent prints to each other. Dated as it seems now, she felt it was as good as anything being done anywhere, with the exception of Stieglitz. In 1914 Wilson’s Photographic Magazine published a selection of her best. She was on her way to becoming well known in American photography. She helped sell prints and paintings of various artists by giving teas. Among them was a young native son, Roi Partridge, an etcher, who because of the war had been forced to leave Paris. They were married in 1915. For the first year they had studios next door to each other. By 1917 three sons had been born, two were twins, they had moved to a small place on Twin Peaks in San Francisco and by 1920 to Oakland. During this time professional photography had ceased except for an occasional portrait, or photographs of plants that various friends had given her for her Oakland garden. In 1921 she started to work again, with a large job for the Bolm Ballet while on tour. When her husband started to teach art at Mills College many of the girls came for portraits. He called it the "Jitter Studio, the Acne of Perfection” because there were so many girls that had to be retouched. About 1925 she started to photograph the magnificent "Pflanzenformen” photographs, ten of which friend Edward Weston selected for display in the American section of the famous Film und Foto exhibition at Stuttgart, Germany in 1929. (Four of these are reproduced on pages 143 through 146.) Directly perceived the forms distinctly emphasized, some of them suggest, in their simplicity, "abstractions” as we use that term so loosely today.

f/64 Group, 1932

Speaking of this never formed, never dissolved, one year and one exhibition, meetings of friends, Miss Cunningham goes on record with an interviewer for the Regional Cultural History Project of the University of California as saying that the instigator was Willard Van Dyke, a cinema-photographer working in the region at the time. To the interviewer’s statement "f/64 has always been considered reflective of American work in photography,” Miss Cunningham answered, "It is not only American, it’s Western American. It isn’t even American, it’s western.” At this 1959 interview she also said of the group, "It’s not that it took shape at all that impresses me, but it’s the quotations you read about it.” And again, "This does not mean that we all used the small aperture, but we were for reality. That was what we talked about too. Not being phony, you know.”

THE MINIATURE CAMERA

A friend returning from abroad in 1938 brought back to Imogen a Zeiss Super Ikonta B. This seemed good to her and she curtailed her work with view cameras (an 8 x 10 for her portraits of Hollywood people for Vanity Fair from 1932 to 1934). By 1945 she had a Rolleiflex and has been addicted to it ever since. These small cameras released her to photography in the rhythm of human expressions and gestures. She wandered about San Francisco’s streets and alleys, in the studios of her artist friends, heaven only knows where. Truly if the light shone on it little escaped her interest. She wrote in 1964, "Now with Tri-X (you see I have a mania for speed) the camera is often hand-held even for grownups. With children almost always, and in our climate, outdoors. I take them where I find them.”

"As one looks at it now (1964), I was greatly handicapped by a 5 x 7 view camera, the only thing I had for years after I returned to the USA.”

Since 1947 she has lived in a small house on Green Street. She lives simply and tastefully in practical surroundings that are expressive of her life and work. She dresses likewise. There is a garden in front. Since 1947 she has taught classes now and then at the San Francisco Institute of Art, mainly in portraiture. It is the private talks however to those students who find their way to her home that really matter. Loaded with wondrous ideas from the various schools in the city she brings them back to their feet before it is too late.

PORTRAITURE

What gives Miss Cunningham’s portraits such intensity? Obviously not the subjects alone. The photographs seem to symbolize a warm relationship between the artist and those who come before her camera. Possessed of a remarkable sense of awareness, she quickly discards artifice and vanity, gets right to the very core of a person’s being. A Cunningham portrait is far more than a record of a personality; it captures inseparably the internal and external individual. Often it bares the soul.

Two excerpts from the University of California interview follow: "Professor Luther with whom I studied in Germany asked me to photograph him at the moment when I thought his thinking was at its peak, and he was doing a mathematical problem in his head. He felt that the photograph was extremely successful. I thought so too. But he was another one of those persons who is always natural. He wasn’t vain.”

"The portrait has to render something that comes from the person himself, and if I don’t get that at all . . . well, I won’t say that I haven’t sold things that I didn’t think were very good.”

"Most people are shocked by their photographs and I have come to the point of seldom having a session with anybody showing them their proofs. What I now do is to send the proofs by mail. When they get them they may take the agony out of their souls before they come to see me. They bring them back and then we can have some kind of a session about it. But when I see them seeing themselves, I am so pained. It’s embarrassing, humiliating, destructive. I can’t take it any more.”

What does it feel like to be photographed by Imogen Cunningham? That must vary with each individual. The editor of Aperture reports his experience in 1963: "We went out of doors in a narrow space between house and fence where the light was luminous. I was seated on the ground amid some dried plant branches. Listening to the overtones of her words, which were not particularly connected, a warmth was communicated. Then her face became beautiful . . . this was the wonder to watch and I gave myself up to the light that seemed to diffuse outward from her face and head. She likes to photograph anything that can be exposed to light, I remembered her saying. Only then did I realize that it was her own light—whether she admitted or even knew it.

Poet, playwright, film-maker, her portrait discloses a man who can skillfully pose a question in one medium and masterfully answer it in another.

“I cannot say that my recent work is very different than anything that I have done previously. I have not been out on the streets as much in the last two years. As usual I trust to the stimulus of the moment to work except when I have to dig up my own stimulus for some real uninteresting job.”

Perhaps the most importance about Imogen Cunningham in 1964 is that she continues to grow in vision, wisdom and love. If one recognizes this love is the matrix from which all her art has developed, the past is clearly revealed and the future can be forecast with lively anticipation. For art, Stieglitz reminded us, is the affirmation of life, and the evidence of life is everywhere, including Imogen.