BLACK AND WHITE ARE THE COLORS OF ROBERT FRANK

Edna Bennett

"Who is Robert Frank? What are his photographs?” The questions come in over a transom of silence—Before me, a collection of his photographs. In me, a deposit of words collected during an interview. Memory stirs the years—first impact of his photographs—this man knows the ways of light.—Light slashes his vision—then stitches the parts; letters following his Guggenheim-fostered travels; check-in talks over assignments; sidewalk conversations constantly interrupted by his camera action; brief meetings with his wife and two children; clattered coffee shop counters echoing talk of was, is, will be.

Who is this man? Who is this man with a camera? He is one and that one is whole. A whole that has not, will not be shattered by conforming to dollar success. Robert Frank, Swiss-born, was a photographer at the age of 18, mainly to avoid further schooling and his father’s business. As an apprenticephotographer, he worked a versatile range from industrial to fashion photography. In 1947, when he was 23, he came to New York to work in the Harpers Bazaar Studio as a fashion photographer. It was there he met Alexey Brodovitch who encouraged him to emerge from the frothy web.

Late in 1948, he made a trip to Peru and Bolivia, then came back to America to work as a freelance magazine photographer. Working with the 35mm camera, he said: "One gets good results very quickly with the small camera. You can’t miss taking passable pictures once you learn the simple knobs. But, with this little machine in the hand, you cannot wait for what is called 'the decisive moment.’ You don’t photograph because you have a camera, you photograph because you have eyes and because you have something to say.”

During the years from 1950 to 1953, Robert Frank did a lot of traveling in Europe— living in Paris, London, Valencia. Tired of commercial photography, he strove to link his inner and outer world in the development of an individual style. As he says: "You must go your own way, as in any creative field. Otherwise, you may be successful in an ability to grind out exposures, but you will only be an imitator.”

For the following two years, Robert Frank worked as a freelance photographer for national magazine publications. He looks back on this period of his working life with some pride, some resignation and not a little frustration. He found it more and more difficult to work independently—from both a materialistic and a spiritual sense. Magazines, who chose to give him assignments because of his individual style and unusual approach, also complained that he was too different; they were too surprised by the pictures he made for them.

Of the photo-journalism field, Robert Frank says—"I am not a pessimist, but looking at a contemporary picture magazine makes it difficult for me to speak about the advancement of photography, since photography today is accepted without question, and is also presumed to be understood by all—even children. I feel that only the integrity of the individual photographer can raise its level.

"Photography is a lonely journey. It is the only road a creative photographer can take. There are no compromises—few photographers accept this fact and perhaps that is the reason why we have so few great photographers. In recent years, the term photo-journalism has become a definition of good photography, especially among magazine photographers. To me, photo-journalism means dictation of taste by the magazine.

"Working on an assignment for a magazine suggests to me the feeling of a hack writer or a commercial illustrator. I resent that my ideas, my mind and my eye are not creating the picture but that the editor’s mind and eye have the final say. If the photographer wants to be an artist, his thoughts cannot be developed overnight at the corner drug store.”

In his early 30’s, Robert Frank was awarded a grant from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation to photograph the American scene. US. Camera Annual—1958 carried a selection of these pictures, and a statement by Robert Frank. In part, he said... "I am grateful to the Guggenheim Foundation for their confidence and the provisions they made for me to work freely in my medium over a protracted period. When I applied for the Guggenheim Fellowship, I wrote... 'To produce an authentic contemporary document, the visual impact should be such as will nullify explanation ..

"With these photographs, I have attempted to show a cross-section of the American population. My effort was to express it simply and without confusion. The view is personal and, therefore, various facets of American life and society have been ignored ...

"I have been frequently accused of deliberately twisting subject matter to my point of view. Above all, I know that life for a photographer cannot be a matter of indifference. Opinion often consists of a kind of criticism. But criticism can come out of love. It is important to see what is invisible to others. Perhaps the look of hope or the look of sadness. Also, it is always the instantaneous reaction to oneself that produces a photograph.

"My photographs are not planned or composed in advance and I do not anticipate that the onlooker will share my viewpoint. However, I feel that if my photograph leaves an image on his mind—something has been accomplished.”

In the same issue of US. Camera Annual, Walker Evans wrote about Robert Frank and the Guggenheim pictures... "Assuredly the gods who sent Robert Frank, so heavily armed, across the United States did so with a certain smile... That Frank has responded to America with many tears, some hope, and his own brand of fascination, you can see in looking at his pictures of people, of roadside landscapes and urban cauldrons and of semi-divine, semi-satanic children. He shows high irony towards a nation that generally speaking has it not; adult detachment towards the more-or-less juvenile section of the population that came into his view. This bracing, almost stinging manner is seldom seen in a sustained collection of photographs. It is a far cry from all the woolly, successful 'photo-sentiments’ about human familyhood; from the mindless pictorial sales talk around fashionable, guilty and therefore bogus heartfeeling.

"For the thousandth time, it must be said that pictures speak for themselves, wordlessly, visually—or they fail.”

Frank’s book, Les Américains, was published in Paris by Robert Delpire in 1958. The following year Grove Press brought out an American edition, minus the French text, which was replaced with an introduction by Jack Kerouac. It was received with mingled praise and condemnation. The feeling seemed to be that the title was all-inclusive, but the pictures were not. Of the reviews, Robert commented—"I welcome criticism if it is intelligent and constructive, but the lack of good critics interested in photography is one of my complaints about photography today.

"Painters, even second and third-grade ones, are taken seriously. They can command intelligent criticism. For the photographer, this is impossible. He has no place to exhibit, no able critics to evaluate his work. It is very hard for him to feel that he is getting real recognition. There is so little for the photographer who really tries. The Guggenheim is the only good thing left. It is pitiful what the museums are doing for the photographer. If they want photography as part of their program, then let them treat it as an art and the photographer as an artist. Otherwise, why do they bother? Why can’t the photographer be accorded the dignity due the serious artist?”

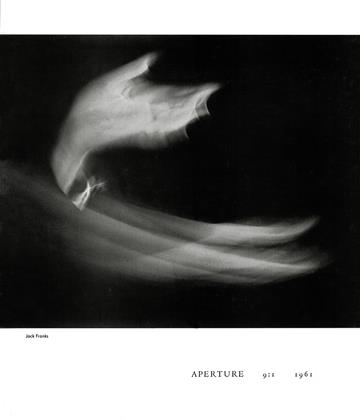

Robert Frank has said of his work ... "Black and white are the colors of photography. To me, they symbolize the alternatives of hope and despair to which mankind is forever subjected. Most of my photographs are of people; they are seen simply, as through the eyes of the man in the street. There is one thing the photograph must contain, the humanity of the moment. This kind of photography is realism. But realism is not enough—there has to be vision, and the two together can make a good photograph. It is difficult to describe this thin line where matter ends and mind begins.”

It might well be said that black and white are the colors of Robert Frank. He is neither highlighted with exhilaration or shadowed with depression, but both are in his personality, as they are in his photographs. He seeks, searches, tries to grasp, to feel, to know himself in all the manifestations that make up a complex personality. Robert Frank does not carry a "chip on the shoulder” as he is so often accused. He is a deeply serious person. Seemingly, he stands aside from the mid-stream, objective and disconnected. This is as false as some of the opinions about his photographs. In reality, he is a tender, gentle, alive and concerned person. He wants with all his being to work as he must—without compromise. And he has the guts to do it though he masks his courage with a smiling jest—"I guess I am able to live cheaper than most.”

As far back as 1954, Robert Frank believed that working in films was a logical extension of still photography. In his search for his own visual images, he has worked mainly in this medium for the past two years. Two movie shorts, Pull My Daisy, co-produced with painter Alfred Leslie, and narrated by Jack Kerouac and The Sin of Jesus, from a short story by the Russian writer, Isaac Babel, have been the result.

Having just completed The Sin of Jesus, which is his own production, I asked Robert what he planned for the future. He wants to stay in films because he feels the challenge is greater and that in this work he can continue the kind of photography he wants to do. He said—"Because of a certain reputation as a still photographer, I could make more money now in that field, but I could not push harder in the direction I would like to go. I feel very strongly that what I want to say in photography—-Yes, I said a lot of it in my book— I can say more in movie work and can say it differently. I can go forward. I have never been satisfied with what I have done. I must keep going. It is a very difficult medium.”

Jack Kerouac said in his introduction to The Americans... "Robert Frank, Swiss, unobtrusive, nice, with that little camera he raises and snaps with one hand he sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film, taking rank among the tragic poets of the world.”

Robert Frank says of all his photography—"Something must be left for the onlooker. He must have something to see. It is not all said for him.”

The onlooker, however, sometimes finds it hard to keep his visual footing when confronted with Robert’s photography. It switch-blades the unsuspecting who were casually "just looking, thanks.”