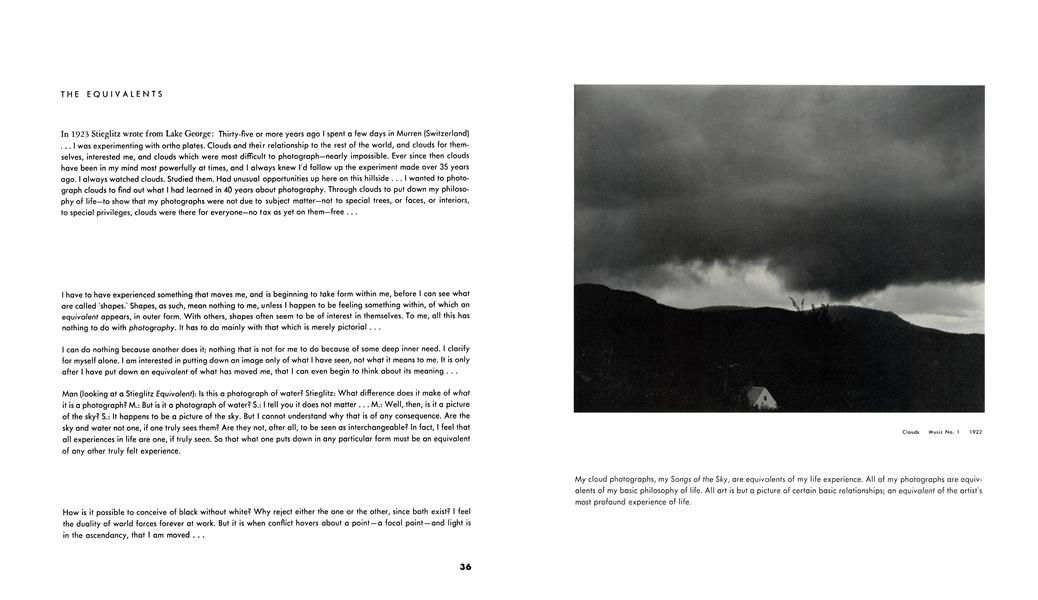

THE EQUIVALENTS

In 1923 Stieglitz wrote from Lake George: Thirty-five or more years ago I spent a few days in Murren (Switzerland) ... I was experimenting with ortho plates. Clouds and their relationship to the rest of the world, and clouds for themselves, interested me, and clouds which were most difficult to photograph—nearly impossible. Ever since then clouds have been in my mind most powerfully at times, and I always knew I’d follow up the experiment made over 35 years ago. I always watched clouds. Studied them. Had unusual opportunities up here on this hillside ... I wanted to photograph clouds to find out what I had learned in 40 years about photography. Through clouds to put down my philosophy of life—to show that my photographs were not due to subject matter—not to special trees, or faces, or interiors, to special privileges, clouds were there for everyone—no tax as yet on them—free .. .

I have to have experienced something that moves me, and is beginning to take form within me, before I can see what are called ‘shapes.’ Shapes, as such, mean nothing to me, unless I happen to be feeling something within, of which an equivalent appears, in outer form. With others, shapes often seem to be of interest in themselves. To me, all this has nothing to do with photography. It has to do mainly with that which is merely pictorial . . .

I can do nothing because another does it; nothing that is not for me to do because of some deep inner need. I clarify for myself alone. I am interested in putting down an image only of what I have seen, not what it means to me. It is only after I have put down an equivalent of what has moved me, that I can even begin to think about its meaning . . .

Man (looking at a Stieglitz Equivalent): Is this a photograph of water? Stieglitz: What difference does it make of what it is a photograph? M.: But is it a photograph of water? S.: I tell you it does not matter... M.: Well, then, is it a picture of the sky? S.: It happens to be a picture of the sky. But I cannot understand why that is of any consequence. Are the sky and water not one, if one truly sees them? Are they not, after all, to be seen as interchangeable? In fact, I feel that all experiences in life are one, if truly seen. So that what one puts down in any particular form must be an equivalent of any other truly felt experience.

How is it possible to conceive of black without white? Why reject either the one or the other, since both exist? I feel the duality of world forces forever at work. But it is when conflict hovers about a point —a focal point —and light is in the ascendancy, that I am moved . . .

My cloud photographs, my Songs of the Sky, are equivalents of my life experience. All of my photographs are equivalents of my basic philosophy of life. All art is but a picture of certain basic relationships; an equivalent of the artist’s most profound experience of life.

WHEN I AM MOVED BY SOMETHING, I FEEL A PASSIONATE DESIRE TO MAKE A LASTING EQUIVALENT OF IT. BUT WHAT I PUT DOWN MUST BE AS PERFECT IN ITSELF AS THE EXPERIENCE THAT HAS GENERATED MY ORIGINAL FEELING OF HAVING BEEN MOVED.

WHEN I AM ASKED WHY I DO NOT SIGN MY PHOTOGRAPHS, REPLY: 'IS THE SKY SIGNED?'

IF ONE CANNOT LOSE ONESELF TO SOMETHING BEYOND ONE, ONE IS BOUND TO BE DISAPPOINTED.

WHERE THERE IS NO EQUALITY OF RESPECT, THERE CAN BE NO TRUE RELATIONSHIP.

If what one makes is not created with a sense of sacredness, a sense of wonder; if it is not a form of love-making; if it is not created with the same passion as the first kiss, it has no right to be called a work of art.

A YES TO ONE'S YES, A NO TO ONE'S NO. THAT IS ONE'S TRUTH, ONE’S RELEASE. BUT ONE CANNOT FIND CORROBORATION FOR ONE'S OWN YES, ONE'S OWN NO, UNTIL ONE IS CLEAR WITHIN ONESELF AS TO WHAT ONE'S OWN FEELING IS. IT TAKES TWO TO MAKE A TRUTH.

When I met Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, the great Indian art historian, in 1928, not long after I had come to know Stieglitz, I asked Coomaraswamy which modern artists in America he admired. He replied, "Not any. And no Europeans either. The very term modern art is an absurdity. The notion that one should attempt to be original in art is sheer nonsense.”

"What,” I inquired, "do you feel about Stieglitz’s photography?”

Coomaraswamy replied at once, and with great enthusiasm, "His work counts. He is the one artist in America whose work truly matters.”

Mystified, I asked why this should be so, since Stieglitz was no more of a "traditionalist” in the strict, Hindu sense of the word, than were any of the modern artists whose work he championed, and whom Coomaraswamy deplored. "Stieglitz’s photographs,” said Coomaraswamy, "are in the great tradition. In his work, precisely the right values are stressed. Symbols are used correctly. His photographs are 'absolute’ art, in the same sense that Bach’s music is 'absolute’ music.”

I then learned that it was Hindu-traditionalist Coomaraswamy’s admiration for Stieglitz’s photographs that led to their being acquired by the Boston Museum in 1924—the Museum never before having opened its doors to photography.

Stieglitz might easily be thought of in terms of Existentialism, or Zen Buddhism, since what preoccupied him most was the reality of experience itself ; the process of becoming, rather than theory about experience, or the "finished product.” But he said of himself : "I seem to be claimed by every ist. Tet no ism in itself has any final meaning for me. All isms contain some measure of truth. Each is but part of a passing phase. I suppose that if I can be said to subscribe to any ism whatever, it may be that I am simply a fatalist. But with one eye on fate.”

"All true art is a picture to me—an equivalent—of a supreme order—in one form or another. Whether it be Christ, a book, a piece of music, or whatever ...” Stieglitz used the term equivalent in still other ways as well: Abhorring all isms, dogmas, theories, generalizations, but being deeply fascinated by attempting to discover what he liked to call the basic laws of life, it so happened that one of the laws about which he felt he had discovered something in the course of his "life-experience” was what he termed the laiv of equivalents.

He liked increasingly to claim that, to him, the Golden Rule was quite without point; that it was entirely meaningless to exhort people to "do unto others as one would have others do unto one” ; to "love one’s neighbor as oneself.” He expressed the belief that there is, rather, a law that functions inevitably—the law of equivalents—do what one may. He asserted that, quite automatically, one does do unto others precisely as others do unto one; one does love one’s neighbor precisely as he loves one—or as one loves oneself. One creates or evokes in others an exact equivalent of what one projects oneself.

When an artist finds his own truth, he will find that it fits in with traditional truths, for traditional truths are but truths that have endured over a long period of time. Originally, however, whether the truth found is a traditional one or not, is never a question that the artist asks, for, as each speaks his own truth from the depths of his own experience, it must automatically be in the great tradition of truth, and it will inevitably have been said precisely so for the first time. It is this that I mean in spirit when I say that all true things are equal to one another.