OBSTACLES TO CREATIVITY and the Teachers' Role in their Reduction

In one of the most worthy articles that the editor has encountered in ages, Dr. Berlin offers suggestions for removing obstacles to creativity that have widespread application. He is a many titled man at the Langley Porter Neuropsychiatric Institute in San Francisco and is intimately acquainted with why students in both the arts and sciences who show early promise often fail to develop into mature artists or scientists.

i. n. berlin

■ As one who has been helped to greater creativity by teachers, I have been interested in trying to understand how I’ve been aided and to make the methods explicit in the process of working with my own students. I’m sure all teachers have experienced the feelings of frustration as promising students give one glimpses of creativity which never matures or is never fully realized. For the purposes of this discussion, I have defined creativity as — that kind of self expression in one’s own medium that results in constant growth and synthesis of experiences essential to the continual production of new and original work.

While I have been primarily concerned with the creativity which produces original thinking in my own specialty of psychiatry, and while my attention to the obstacles to creativity has been centered on my own students who show promise, I’ve also had the opportunity as a psychotherapist to work with several writers, painters, sculptors and photographers, where these obstacles have been of primary concern in the treatment. My own avocation of photography has widened my horizons further and provided additional opportunities to see other teachers in another field try to deal with the same problems in their students.

These efforts to crystallize some of my thoughts of the past few years in writing are the result of reading two recent papers.

The first is Walter Rosenblum’s ' Teaching Photography”, published in APERTURE, Vol. 4, No. 3, 1956. 7’he second is Irving Sarnoff’s "Some Psychological Problems of The Incipient Artist”, published in MENTAL HYGIENE July, 1956. Both articles stimulated trains of thought which had not quite crystallized and helped me make these thoughts more explicit. Sarnoff in his paper reviews his experiences as a psychotherapist in a University Health Service with a number of promising students in the arts. He discusses three fears which prevent creativity. The first is the fear of ass/nning a position of authority which permits the artist to place the stamp of his perceptions on the world. In my own words this means to accept one’s role as a mature adult, who can assert his ideas authoritatively and is thus the equal of others in the same field and especially the equal of authoritative persons from one’s childhood, one’s parents.

The second fear is the fear of talent, the anxiety about committing one’s self to the unremitting work of developing one’s creative capacities, to bearing the frustrations, hard work and responsibility of seeking self-fulfillment. Sarnoff points out that many young artists are dismayed when they do discover glimpses of their talent. They would rather continue to be promising aspirants in their fields rather than be committed to the development of clearly evidenced talents.

The third fear Sarnoff mentions is the fear of inner emptiness or the anxiety that there are few inner resources, that they will soon run dry and leave the artist without any foundation for further work. In Sarnoff’s clinical examples, the artistic production is felt as a loss of substance by students who still feel the need for continual gratification from others.

My own point of view on creativity and the hindrances to its realization is in large part the result of training, research, teaching and practice of child psychiatry or more accurately, family psychiatry. My particular research interest in childhood schizophrenia has both provided opportunities to work with children whose creativity is almost non-existent, whose capacities for learning are stunted, and with their parents who in several instances were talented people with creative potential never fully realized. It was in such a setting that the problems around creativity, and the inhibiting factors which result from the child’s experiences with the adults in his life became vivid to me.

Perhaps the conflict most evident in the schizophrenic child can be seen in his very attitude, the stiff awkward movements, the frozen demeanor, the paucity of speech and the general inhibition of emotion except for destructive rages. As one works with such children and their parents one becomes aware of the dove-tailing conflicts in the parents about their freedom to be aware of ail feelings. Such conscious and verbal awareness of feelings gives one the conscious choice about how any feelings could be expressed non-destructivcly. These parents feel it dangerous to experience freely and fully many emotions. One usually learns that in their childhood such feelings as anger, hate, acute disappointment, or sensual and sexual feelings were forbidden verbal expression. Or that such suppression increased the possibility of imminent discharge of such feelings into destructive or forbidden behavior and aroused massive anxiety. Thus these parents who were talented and even successful in earning their living in graphic arts, writing, etc., were usually unable to consciously feel emotions so that their work failed to breathe of life. They tended to do acceptable, fairly stereotyped not very imaginative work from which they made their livelihood, but which never gave them a feeling of selffulfillment. In the course of psychotherapeutic work with both the children and their parents, it became clear that the unconscious conflicts which result in repression of feelings consumed a tremendous amount of energy. Thus they were constantly fatigued, their productivity was reduced and even their perceptivity was markedly diminished.

Obviously there are many other aspects of conflict which inhibit creativity and were evidenced in these children and their parents. Another aspect of the conflicts which resulted in the massive inhibition of feeling were those conflicts which centered around learning. In the child, often learning such things as self-care and later learning in school, was markedly inhibited. All aspects of learning at every developmental stage can be viewed as preparation for the fullest living and learning in the next stage of development so that in adult life one functions as an individual with other persons but is not parasitically dependent upon them forone’sbeing able to live. The schizophrenic child especially evidences a great fear about learning. Learning seems to mean to him to "grow up’’, that is, to cease being a helplessly dependent child and thus to preclude forever, obtaining the gratifications he has not yet received. It is clear that in this area these children have not had the experience of participating with their parents in the mutual pleasures of infancy around feeding, daily care, playing and learning. The parental conflicts reduce markedly the parents’ tender assistance to the infant and child in learning and in physical and emotional development. These conflicts resulting from their own unmet needs in childhood greatly diminish the parents’ enjoyment and thus their ability to behave as parents with their child. In their living as adults these parents seek satisfactions from other adults not as coequals, but as helpless dependent children whose needs often must be met, so that they can continue to function as adults in other aspects of their living. Thus such parents not having been helped by their own parents to mature adulthood are not free to explore the resources both within themselves and in the world around them. They are inhibited and restricted by their conflicts from childhood, from freedom in thinking and feeling. To both the parents and the child independence continues to portend the loss of satisfactions from others.

These observations substantiate the conflicts Sarnoff describes in his art student patients. The fear of asserting one’s own thoughts, beliefs, insights, feelings seems to meto be essentially a conflict about learning to learn for one’s self, for to feel the constant urge to grow, develop, explore and create means to give up parasitic dependence on parents, parent figures, teachers and others. The anxiety about accepting one’s talent and the hard work which its full development entails is in my thinking related both to the desire to continue to be fed and supported by others rather than going on alone as well as the anxiety about consciously experiencing within one’s sell the full gamut of human emotion. Having never learned that it is possible to feel fully all feelings without their eruption into destructive behavior, it is difficult to live with these feelings and permit them full conscious, verbal awareness so that they can be translated into creative work. Sarnoff’s third conflict about the fear of inner emptiness and lack of sustaining resources, I would also ascribe in its origins to the fear of exploring the gamut of emotions in all their violence, turmoil, and loving tenderness with consequent repression of these anxiety provoking feelings. Such repression often results in feelings of void and emptiness, a sense of something missing, a feeling of looking for something usually from others and a continuing belief that one’s inner resources are limited. To begin to explore those resources in order to find within one’s self, fullness of feeling and unlimited creative capacity, continues the anxiety about loss of sustenance from someone else, for the anxious tension does not abate until one has learned, over a period of time, the perseverance necessary to make one’s own resources available to one’s self.

Case illustration*

A successful commercial photographer consulted me because of recurrent tension headaches, continuous feelings of hate and anger with frequent explosive rages which just stopped short of physical violence. His feelings and behavior inhibited his effectiveness with clients, his relations with coworkers and, threatened his marriage. The recurrent severe headaches and a constant tired feeling also markedly reduced his productivity and each job was completed with great effort. Since he was aware of my interest in photography he occasionally brought in examples of his work. These were invariably well thought out, meticuously executed advertising photographs of the same caliber as those found in then current magazines. It was only after many months of work together that he began to describe his impulses in each job to make photographs which expressed more fully his ideas and feelings. At such times he experienced massive anxiety. He felt that such departures from the usual commercial work would be deprecated and rejected by his clients and thus might call forth his uncontrollable rages. He felt safest although tense, unhappy, discontented and unfulfilled when he

*The work here presented was done so long ago that the

person cannot be identified.

made the "slick, run-of-the-mill" photographs. At such times he also had severe, and almost intractable headaches. During this period of our work he began to bring in occasional "Sunday" photographs. These gave hints of his creative ideas and feelings, but they gave me a sense of being inhibited and restricted as if on Sundays he were trying desperately to make up for his weekday dissatisfactions. My patient expressed his continued dissatisfactions with these pictures too. In addition it became clear that Sunday photography added to the tensions of his already strained relationship with his wife. In time he began to work through some of his problems which centered around his very prosperous and domineering father, who although financially successful failed to achieve the eminence and recognition he felt was due him for his processional achievement. His father violently disapproved of his early leanings towards Art and of his eventual decision to seek training in photography. My patient had vivid memories of the many times in childhood that he brought his pictures to his parents only to face his father's scorn and ridicule and his mother's extravagant praises and idolization. These conflicting attitudes and their effect on him were a recurring theme in our work. Gradually he was able to dissociate his clients from his feelings about his parents. His fear of their scorn, hope for their adulation and praise. At the same time he began to see his wife in a new perspective. He saw her originally as the person he hoped would sustain him with admiration, uncritical praise and constant attention to his needs. Thus her often valid and constructive evaluations of his work my patient felt as his father’s scorn and deprecation. When she voiced her needs in their relationship he could only feel hate and rage at being asked to "give" when he was in such dire need himself.

In time he began, first in a few instances, to present clients with both the standard photographs and those which expressed his own creative ideas. To his surprise and satisfaction a few clients preferred his creative ideas. Thus encouraged he began to present more freely his own ideas, to follow his own creative urges with increasing success and contentment. His relationship with his wife improved, his headaches markedly reduced and his rages were more and more infrequent. The ' Sunday'' photographs that he brought reflected his increasing freedom of seeing and feeling.

As my patient gained more perspective about himself as an adult and felt easier about himself and his relations with-people, he was able to show his father some of the photographs which were most satisfying to him. To his surprise his father expressed admiration and appreciation of the work he was able to do.

How then can the teacher help those students who show promise of creativity and to some degree, in various proportions some of the inhibiting factors just mentioned. First the teacher must be aware that he may not be able to be very helpful to some students no matter how hard he tries. Their obstacles to creativity are of such degree that another kind of help, as just illustrated, may be necessary. But he could be of much assistance to many students.

Walter Rosenblum in his beautiful article gives a clear example of how a teacher may behave in such a way with his pupils so that they identify with his attitudes towards his work, and towards life. It is both through the process of identification and the teacher’s consistent help to the student in achieving mastery of the subject that new learning occurs and some of the old conflicts and fears somewhat resolved. To quote Rosenblum, "Through past experience I have learned that the teacher cannot push, he cannot provide pat answers, he cannot anticipate problems before they arise, . . . The guidance must be gentle and never hurrying. This development can only proceed under self-propulsion.”

Here, I feel, Rosenblum is saying that he is behaving with his students not as their parents may have, parents who want the child to succeed for the sake of the parents own lack of achievement, to make up for their own frustrations. The parents in living through the child may prevent the child from developing his resources for his own satisfactions. Thus the patience, the lack of an attitude which says I know all the answers helps the students gradually to begin to find them within himself and for himself.

Rosenblum’s emphasis on helping the student to become aware of the emotional impact of his environment bespeaks of his own freedom to react freely without shame with his own feelings to everything about him. He thus provides a model for the student groping towards self-expression.

I’m particularly struck by the succinct and beautiful way in which Rosenblum points to the heart of the teaching relationship. That is helping the photography student become consciously aware of his world. The emphasis on conscious awareness is indeed the touch stone as he points out. "The word conscious is the keyword, for if his feelings remain on an unconscious level, it then becomes impossible for him to grow, on the basis of his past experience.” Rosenblum thus makes the effort to help the student verbalize his feelings, hunches, and ideas. I’m certain that Rosenblum himself must give evidence to his students that it can be done and thus help them to feel free to put into words nebulous feelings, ideas, presentiments until they become crystallized. The atmosphere provided by the teacher must make this possible. In addition, the teacher must provide a model for the student in terms of what can be done by this means. He must himself be a creative practitioner of his art. The atmosphere of respect for the individual humanness and potentialities of his pupils is an absolutely essential ingredient of the teacher’s attitudes. This attitude is implicit in the writing of Rosenblum.

I had a recent experience with another great artist and teacher of photography which further crystallized my thinking about the teachers’ role. In a recent workshop with Ansel Adams the students were of varied capabilities, talent, maturity and even basic photographic knowledge. My own first feeling was how much could be done with so variegated a group. I was interested in Adams’ belief that they could all be helped no matter where they were in their development to take a further step. This basic respect for the individual and his potential was perceived by everyone and was an important factor in promoting their learning of material difficult for many to grasp. The attendant enthusiasm and endless patience, a willingness to repeat material, to give examples until the student was clear, were also factors important to the students learning. Another important factor was the completely honest but gentle criticism of the students’ work. Helping the student face the reality of his present state of development and the work necessary to proceed to realize one’s self further is an absolute essential in freeing students to be more creative. They are helped to divorce themselves from pretenses, and selfdeceptions which permit them to go on without self-realization. Such self-deceptions have often been fostered by parents, husbands or wives who themselves have never been able to face the realities of both their present accomplishments and the work necessary to really satisfy themselves. Such parents often dissemble with their children about their school work, art, writing, music, etc., fearing to hurt the child. They are aware of how they too would feel if the actual truth about their own accomplishments were told them and a course of work laid out. Parents who have not learned to work for themselves, regularly, and persistently can’t believe that it can be done by others and they often know of no solution but unreal, deception of the child. Thus the teacher who has achieved his creative stature by just such regular, persistent work and self exploration can honestly face the student with his present status at the same time expresses his confidence in the student’s potential and his readiness to help. His own example that it can be done is a vital factor in the learning of the student.

The teacher’s attention to all the small and seemingly minute details of the student’s work is often protested against and felt as unfair by the student. He often believes the teacher is failing to recognize the worth of the idea or general concept. However, such attention to small details, the teacher knows, is essential for the student’s complete mastery of his medium and his self-mastery. Sloppy work, unfinished details bespeak of the old conflicts about doing work with all one’s energies and to one’s own complete satisfaction. It indicates the tendency to start many times with ideas which are then left in a state of incomplete fruition. The student may thus deceive himself and others about the worth of the work. The readiness to do a complete piece of work also bespeaks of one’s readiness to do the work alone without the overseeing of a teacher or parent which is a final evidence of creative maturity. -

The meticulous attention to small details even of matting a print, and the lighting of a finished photograph by a master like Adams was a constant source of wonderment and delight to many of his pupils.

The process of learning through identification is basic to all learning. The child begins to learn through the identification with his parents’ attitudes. The student learns much through his identification with his teacher. Such learning when coupled with the complete mastery of subject material is not imitation, it is the integration of attitudes about the self, about how one finds self satisfaction and self fulfillment, it is the integration of a philosophy of growth and creativity which permits one to explore one’s own potential rather than imitate others. One can often see in the students the attitudes of the teachers. Thus in

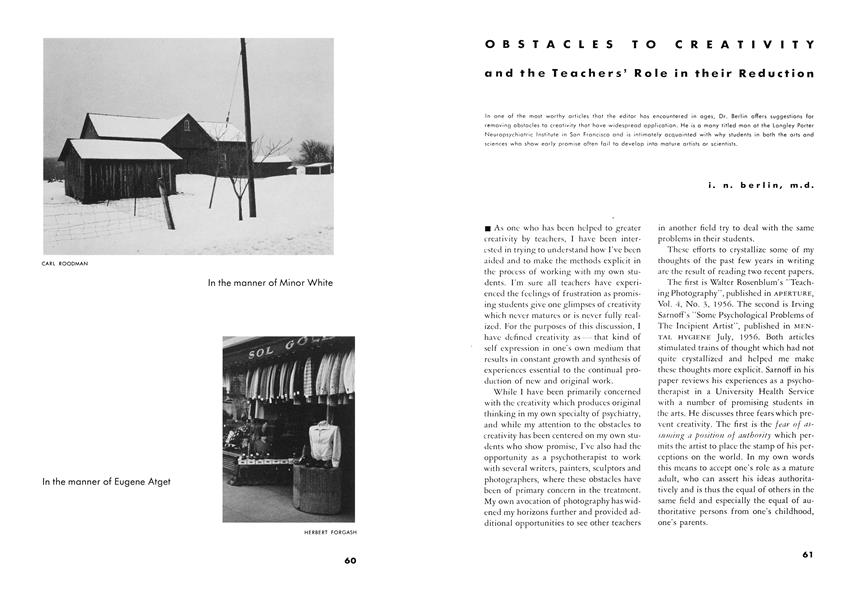

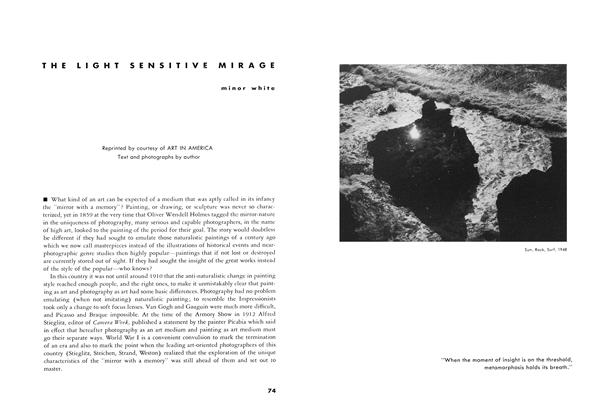

the issue of APERTURE in which Rosenblurn’s article appeared, there was another article with similar breath of approach to the philosophy, teaching and learning of photography and I was not surprised to find that the author, Jerome Liebling, was a student of Rosenblum’s. Although I know Minor White only through his photographs and writing, I have often been able to guess correctly who his students were because their attitudes revealed in their work, conveyed some of his general philosophy toward life and toward creative seeing. This is true of students of Ansel Adams who give evidence of a particular kind of perception, perhaps best described in their efforts to unify the elements in a photograph to present a beautiful and cohesive whole whether the subject be macro or micro-cosmic in nature. They also have the same basic respect for people and their work. It is also true for the students of my own teacher and I hope of my own students. In conclusion, here is a quotation from THE PROPHET by Kahlil Gibran which we inscribed in a compilation of my teacher’s writings presented to him at an anniversary of his work with us. The teacher .. . if he be indeed wise, does not bid you enter the house of his wisdom, but rather leads you to the threshold of your own mind.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

The Light Sensitive Mirage

Summer 1958 By Minor White -

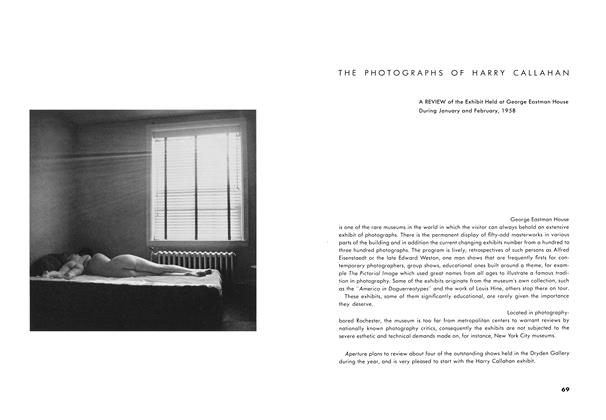

The Photographs Of Harry Callahan

Summer 1958 By Minor White -

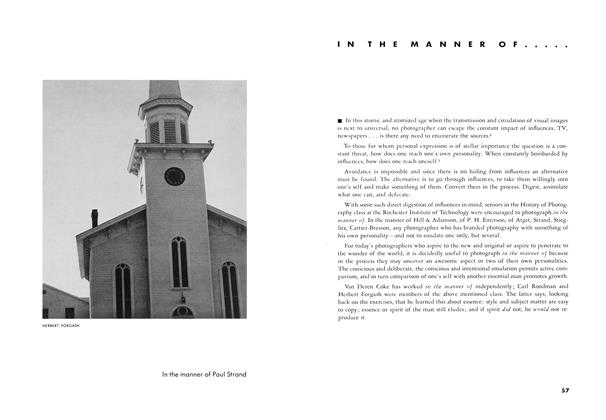

In The Manner Of.....

Summer 1958 -

Group 15 — Portland, Oregon

Summer 1958 By Gerald H. Robinson -

Application Of A Formal Method For Reading Pictorial Photographs

Summer 1958 By James Durrell Jr. -

Notes And Comments

Notes And CommentsVarieties Of Response To Photographs

Summer 1958