SUBSTANCE AND SPIRIT Of Architectural Photography

THROUGH THE FACTS TO WHICH CAMERA WORK IS LIMITED, SOMEHOW SPIRIT

Alfred Stieglitz might have strung the above words together in that very order some time during his talks with people about the essence of picture-making photography. Since the "quote" concerns the essence of camera work, it must also apply to architectural pho tography. To see how we need only ask "what spirit ?" and answer, "the animus of the building, the street, the city"; or, from a sufficient body of photographs, "the life of architecture".

Spirit or essence is not caught on hooks, nor netted like butterflies; not trapped like mice and bears, nor is it copied, nor imitated; nor is it hypodermically inj ected as photog raphers wistfully hope. Greater preparations than any of these are necessary: perhaps only through a constantly growing personal stature on the part of the architectural photog rapher may essence be reached. These pages are pointed at growth, aimed at the everyday business of preparing mind and feelings for photographing architecture rather than tech niques which are amply covered elsewhere as are the warnings to make sure a ladder is in good repair before climbing.

Resemblance reproduces the formal as pects of objects, but neglects their spirit; truth shows the spirit and the substance in like perfection. He who tries to trans mit the spirit by means of the formal aspect and ends by merely obtaining the outward appearance, will produce a dead thing. CHING HAO

ABOVE ALL ELSE THE ARCHITECTURAL PHOTOGRAPHER MUST HAVE FAiTH THAT SURFACES REVEAL INNER STATES

FAITH IN HIS MEDIUM, HOWEVER, IS NOT ENOUGH: INSIGHT MUST BE HIS SO THAT HE MAY DISCERN THE ARCHITECT IN THE MORTAR, THE UNSEEN INHABITANTS IN THE ROOMS AND BEYOND THAT THE SEPARATE LIFE OF ARCHITECTURE

Architecture is environment, the stage on which our lives unfold.

BRUNO ZEVI

Too many photographers turn to architectural photography, either occasionally or professionally, with no more than a nest-building instinct to guide them. While we yield to this instinct its due respect, we, the audience of the architectural photographer, have a right to expect more, especially from the professional. We can expect that his pictures stem from study: that he knows why historian Sigfried Giedion can say that "Architecture has a life of its own” ; why Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius can write "Modern Architecture is not a few branches from an old tree—it is new growth coming right from the roots” ; we can expect that he recognizes the academicism Frank Lloyd Wright scolds when he writes "Time was when architecture was genuine construction, its effects noble because true to causes”.

Above is the intellectual side of the architectural photographer’s preparation. On the emotional or feeling side we can expect that his pictures originate in a heightened ability to stand still in a room, hall, porch, walk quietly in a garden, street or courtyard and feel the breathless breathing of architecture. Or, in our present, ride just fast enough over a cloverleaf interchange to feel space-time through the seat of his pants. We should expect and even demand that his pictures help us sense the heart-beat which an architect, or community of cathedral builders, gave to stone, wood, glass, steel because he has felt that pulse in his own veins.

We have every right to ask these ideals because just as there is good and bad architecture —good when it ennobles, bad when it degrades—so do we have good and bad architectural photography and for the same reasons and the same effects.

Pertaining to ethics: should an architectural photographer make an ennobling photograph of an example of degrading architecture? Assuming that he had the inner stature to photograph a piece of jukebox architecture so that the photograph was an affirmation of ascending spirit, can he afford the lie?

Each must make his own decision.

We are more or less aware that recently the history of architecture is influenced in a dozen subtle ways by what can be photographed ; yet it seems desirable to discuss the subject with more of an eye on the responsibilities of the architectural photographer to his contemporaries, to architecture, to history, to good and evil.

On the Intellectual Side

The architectural photographer should learn to approach his mystique of interpretation with a lively interchange between intellectual knowledge and a craftsmanship of feeling. The intellectual side is mainly conceptual, expressible in words and usually indirect. Knowing where a given example fits in history, or in the economics, or the technical features will help slant the photography ; whereas the feeling side is direct, wordless, a way of evoking the insight needed on the spot to reach essence. The more experience he has the better he knows how and when to bring his intellect into play and how and when to let his feelings take over.

Architecture is a social art. It becomes an instrument of human fate because it not only caters to requirement but also shapes and conditions our responses. . . . It modifies and often breaks earlier established habit.

RICHARD NEUTRA

Good architecture should be a projection of life itself and that implies an intimate knowledge of biological, technical and artistic problems. But then—even that is not enough. To make order out of all these dißerent branches of human activity . . .

WALTER GROPIUS

To maintain that internal space is the essence of architecture does not mean that the value of an architectural work rests entirely on its spatial values. Every building can be recognized by a plurality of values: economic, social, technical, functional, spatial and decorative. The reality of a work of art, however, is the sum of all these factors; and a valid history cannot omit any of them.

BRUNO ZEV1

Architecture is illuminated not only by light but by sound as well; in fact it is brought into relief for us through all our senses

RICHARD NEUTRA

• The fourth dimension (time) is su/JI cient to define the architectural volume, that is the box formed by the walls which enclose the space. But the space itselfthe essence of architecture-transcends the limits of four dimensions.

BRUNO ZEVI

Louis Sullivan spoke of the building (or the ornament) as growing organically, unfolding from the procreant power of the germ idea. He said FORM FOLLOWS FUNCTION. But he also said The best of rules are but flowers planted over the graves of prodigious impulses." He said FORM FOLLOWS FUNCTION: and be spoke not of the functions of the sailing ship and the broad-bit axe, as had Horatio Greenough, but of the functions of the rosebud and the eagle's beak. . .

JOHN SZARKOWSKI

Architecture as the unending sum of pos itive gestures. The whole and its details are one.

LE CORBUSIER

Chartres is the flower of a time, having its roots in the deeper emotions of a people who were sharply focused upon religion and ivho sought the relief of outward expression. Religion was a great mass consciousness, and by the projection of the cathedral the welcome oppor-

tunity was given them. Every age manifests by some external evidence ... it may be true, as has been said, that our factories are our substitute for religious expression.

CHARLES SHEELER

Good organized architecture depends just as much on an understanding public as on its creators.

WALTER GROPIUS

Architecture sums up the civilization that it enshrines, and the mass of buildings can never be better or ivorse than the institutions which have shaped them.

LEWIS MUMFORD

On the Feeling Side

Once early in his career the architectural photographer must "live” with a great building: bridge, skyscraper, park or other until the essence of it has seeped into him. And changed his life! With the unforgettable experience of even a great barn—these rural cathedrals that are occasionally seen—he will always know what to wait for when he starts to photograph a building new to him.

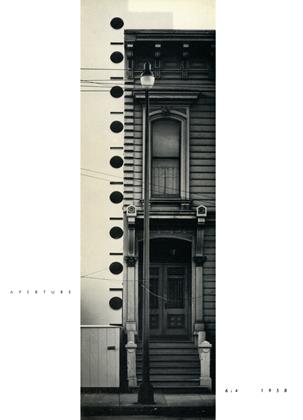

The photograph on the opposite page seems to originate in a heightened feeling for architecture. Englishman Fredrick Evans at the turn of the century had a reputation for achieving a remarkable state of harmonious affinity with the cathedrals that he sought out in Britain and the Continent. Something of this rapport enlivens his photographs. Such a reputation is downright important to the dependent spectator who has never seen, say, Kelmscot Manor and so can not compare his feeling aroused by the photograph with that evoked by the attic.

When a photographer has earned a reputation for insight and for honestly knowing when the feeling aroused by his photograph is equivalent to that aroused by the original, the spectator is free to accept the feeling evoked in him by the photograph as true to essence—so far as that is humanly possible. When a photographer has earned a reputation for a more personal approach to architecture his pictures are valuable for other reasons. According to art historian Bernard Berenson honest photographs by men of perception and taste are certain to give the spectator viewpoints to which by his own temperament he is blind. Architectural historians are often avid consumers of all photographs, good and bad alike, of architecture of the stature of a Notre Dame or a Massachusetts Turnpike because a wealth of opinions temper their own. What photographer is so universal that he can hear all the echoes of a Chartres or an Empire State Building ?

Today’s professional architectural photographer has the responsibility of achieving a reputation, a reputation for a feeling for architecture. Is there any reason why his reputation should not be equal to that which Fredrick Evans earned in his lifetime ? And beyond a feeling for architecture he should know how to make the feeling evoked in the spectator (not in himself) by the photograph be equivalent to (not equal to) what the spectator would have experienced in the original. This part of his camera work is not expressive, not insight, not art, but a hardy craftsmanship of feeling.

Chartres became one of the outstanding experiences of a lifetime. . . . The approach to the town, with the cathedral seen towering over it from its elevation —the increasing detail upon drawing near with an ever increasing emotional response—arrival at the portal—then the moment of entering—a sense of peace— the brief illusion that by accepting the religion that brought it into being this sense of union could be per petratedthe realization that this was a moment not to be made captive.

Out into the sunshine again—ivalking and looking: but no photographs. Something of the ego of the artist must be restored before the illusion of equality could be re-established, and work could become possible.

CHARLES SHEELER

It should not be assumed that a photographer—or a critic!—can grasp in five or ten minutes what took the sculptor or architect months or years to create.

HELMUT GERNSHEIM

... A building is not merely a sight; it is an experience! And one who knows architecture only by photographs does not know it at all.

LEWIS MUMFORD

CONFLICT

Even though photographs cannot substitute for the actual experience of architecture certain advantages lie within photography’s limitations. In its ability to record only a small segment of the total impression is the advantage of abbreviating to the point of clarity—in pointing out and intensifying the essentials of any impression.

NORMAN CARVER, JR.

ASSUMING THAT MUMFORD IS RIGHT, THEN THE ARCHITECTURAL PHOTOGRAPHER GOES TO WORK WITH FAILURE IN HIS CAMERA. HIS STRENGTH LIES IN THE BELIEF THAT THE EXPERIENCE OF A PHOTOGRAPH CAN BE THE ECHO OF AN EXPERIENCE OF A BUILDING HE THRIVES BECAUSE HE NEVER UNDERESTIMATES THE VALUE OF AN ECHO!

According to Frank Lloyd Wright architecture is not bounded by four dimensions but more, many more: Alfred Stieglitz claimed that camera work is dimensionless. When camera work is employed to record architecture, however, the dimensions are sharply reduced. Time is their common denominator. Three dimensional space is an illusion in photography—though Baroque buildings exploit the same illusion. Light, as Le Corbusier says, is the loudspeaker of architecture. Common denominator though time seems, though they share the present, time is not identical for photography and architecture.

SPACE & TIME ARE OF THE ESSENCE OF ARCHITECTURE. TO ECHO ARCHITECTURE THE PHOTOGRAPHER USES A MEDIUM WHOSE ESSENCE IS TIME & LIGHT

On one hand the present is the exact instant, never to be repeated : for example the long shadow at precisely 7:19 A.M. March 19 which magically reveals the essence of a building in such a way that the camera can see it. But morning and March come again, and again ; and the building may change so little meanwhile that to our gross senses the exact moment of revelation repeats. On the other hand the present is also longer periods ; the revealing moment endures in some instances for hours on every grey day and night after night. Under these conditions a fraction of a second is the same length of time as an hour and camera work experiences time as buildings do.

Observe last year’s photograph of a building now bombed out and another dimension is experienced: one is aware of the life of buildings and then of the separate life of their photographs.

Time is the least comprehensible, the most elastic of all the curious qualities of photography—this medium at once commonplace and sur-realistic, familiar and esoteric.

TO INTERPRET OR TO RECORD

Though some writers on the subject take definite sides, to interpret or to record is not at all like living between the devil and the deep blue: the best architectural photography is always something of both. Author after author says in one way or another that the ideal architectural photograph is a record of an interpretation of facts. Yet some favor factual reporting and others interpretation and stake their claims. We feel that both have a definite and logical place: one is more appropriate to geometrical architecture, the other to asymmetrical architecture—if we may make such sweeping generalizations.

We propose to follow in the footsteps of Heinrich Wölfflin, German art historian who developed a set of concepts for analyzing modes of vision in the arts and architecture. We propose a range or scale of balance between interpretation and record. On one side the balance shifts in favor of interpretation, on the other the shift is in favor of record. The six photographs which follow illustrate the scale including the excesses of what can be included in the definition "the architectural photograph is a record of an interpretation of facts”. As we shall see the interpretative mode carried too far becomes exploitation of subject matter, and conversely the record mode carried too far becomes witless.

While the terms are not fully descriptive, we will call one side of the scale "interpretative” and the other "making facts speak for themselves”. As any architectural photographer will agree, making facts speak for themselves is a highly interpretative act! The creative energy necessary to interpret is exactly the same as required to make facts speak for themselves.

A SCALE OF MODES: The Interpretive Mode (Romanticistic, organic)

Starting with the interpretative side of the balance, the above photograph seems to be an obvious example of interpretation that exceeds the bounds of architectural photography. The information given about the cobble stone house in upper New York state is incidental to the statement that a house has relations, normally invisible, to land and seasons. Some persons may argue, however, that showing such relations, because rarely seen, is no cause for excluding the photograph from the class. The boundaries of architectural photography will remain hazy. Coburn’s photogravure of St. Paul’s in London is on the borderline between exploitation and interpretation. Again the spectator can decide for himself whether this is more Coburn than Cathedral, or, only a little more Coburn than the evocation of the very living

spirit of Christopher Wren’s church.

Like architecture its photographs may be considered from more than one viewpoint. These two photographs also illustrate the style of two photographers working about fifty years apart. Both are romantics, Coburn in a style prevalent at the beginning of the 20th Century and White in the manner of the mid-century straight photographers. Something of the period affects photographers as well as architects; hence the spectator of photographs must learn to make allowances. The influence of period is one more veil that must be pushed aside to see the architecture.

The detail by Norman Carver, Jr. is rendered factually enough, yet out of context as here may seem exploitation of subject matter. In its place in a book on Japanese Architecture it crystallizes many pictures and symbolizes the feeling that photographer and architect Carver has towards one of the most integrated traditions of architecture in the world. In another direction this symbol reflects his convictions about modern architecture, "the need to find in architecture those abstractions that approach the essence. ...”

Chodzkiewiez in his long series on Fontainebleau achieves an almost even balance between interpretation and letting facts speak for themselves. For those spectators willing to project themselves into the photograph the spirit lies just beneath the surface.

But relate the pictures on these two pages ! Half a world apart in space, five decades in time, two cultures, yet thought of together and some kinship is felt that goes far deeper than similarities of a few shapes.

THE THINGS-SPEAK-FOR-THEMSELVES MODE (Classicistic, geometrical)

On the side of the scale called ' facts speak for themselves” the photographer makes a great effort to be the thinnest possible ghost between the spectator and the architecture.

Observe the qualities: substance almost everywhere, the light gives form to the buildings instead of changing form, the formal position of the camera is impelling—the frontal position frequently promotes the feeling of integrity that comes from looking at things for what they are. This position is appropriate to the Round House, arresting in the monastery wall.

Both of these pictures are comfortably within the limits of architectural photography. Beyond this, which is not illustrated, stands the witless record. The document fails when things can not speak for themselves because they are gagged by a lack of perception.

Throughout history there persists two distinct trends—the one towards the rational and geometrical; the other towards the irrational and the organic: two different ways of dealing with or of mastering the environment.

SIGFRIED G1EDION

In the quotation above Giedion also follows Wölfflin. And since they divide mankind as a whole into two temperaments, architectural photographers can probably be included as well as the builders and architects. The two trends have several opposite qualities: intellectual as opposed to emotional ; a regard for things as they are as opposed to a fascination for things as they are seen in relation to each other and to environment—or as Wölfflin says "things in the process of becoming”. There are more opposites. The photographers such as Coburn and Evans favor interpretation and so belong to the organic trend ; photographers such as Chodzkiewiez or Nickels belong to the geometrical trend. As Aaron Siskind says the latter group practice "an aesthetic restraint, which is after all basic to all documentary photography.” The temperamental differences are deep and rarely to be crossed. For example the very assets of the organic temperament, his "romanticism”, is hurled back at him as an epithet by members of the opposite camp: and he, not slow at adding insult, declares that the desire of the rational minded photographer to say out of the picture, to let things speak for themselves is evidence of a lack of insight.

Spectators also belong to one trend rather than the other and, as might be anticipated, this has a bearing on how they respond to architecture, to architectural photographs and to vision. And here like is sympathetic to like. The organically oriented spectator is uncomfortable when viewing photographs unless they show a positive interpretative bias and will call dead pictures which the geometrically oriented spectator finds a gate to spirit. The "rational” spectator welcomes the opportunity to read the facts for himself and relishes the assurances that if he brings his own insight to act he will reaach the essence of the sample photographed. The temperamental differences are just as deep here as in the photographers—the "rational” kind often resents and rejects off-hand photographs which show a veil of personality.

Romanticistic---Classicistic

The baroque neutralizes line as boundary, it multiplies edges, and while the form in itself grows intricate and the order more involved, it becomes increasingly difficult for the individual parts to assert their validity as plastic values; a (purely visual) movement is set going over the sum of the forms, independently of the particular viewpoint. The wall vibrates, the space quivers in every corner.

Classic taste works throughout with clearcut, tangible boundaries; every surface has a definite edge, every solid speaks as a perfectly tangible form; there is nothing there that could not be perfectly apprehended as a body.

HEINRICH WOLEELIN

The spectator is rarely as involved as the photographer and so with some training can be brought to an awareness of his own temperamental direction and later to enjoy photographs made in the mode to which he is not naturally sympathetic. The professional photographer, on the other hand, has to learn to expand his natural leanings because he must photograph an organic glass block one day, a Greek revival house the next and poured concrete Gothic later on. He has to learn to cross over at will from the great class of what Wolfflin names "classicistic” architecture to its opposite "romanticistic” (Baroque, organic modern, etc.) If the photographer is able to reveal with assurance the essence of the mode of building to which he is sympathetic, as a professional he must be able to evoke the spirit of the other mode with equal competence. To do this he must learn a craftsmanship of feeling by which he can expand his own temperament as far as possible.

Our appreciation is conditioned by the photographer’s interpretation much in same way as intelligent enjoyment of music is dependent on the interpretive powers of soloist or conductor. HELMUT GERNSHEIM

In the ideal case, recording accuracy is blended with sensitive interpretation of the meaning of a three dimensional work of art and with the creation of an independent work of two dimensional design. NIKOLAUS PEVSNER

Our photographs are based on an objective study of meaning of the architecture —at least four specialists explained to us at one time or another the important aspects of Sullivan’s work: we heard opinions and examined other architectural photographs—not on private preference.

. . . an esthetic of restraint came out of this group work, which is after all, basic to all documentary photography. AARON SISKIND

Sculptor Pevsner in the quotation above champions the classicistic mode. Photographs which are independent units in their own right, in a general way, are appropriate to the architecture which stems from the same mode. This ideal, however, with which Pevsner would blanket all of architectural photography is not appropriate to architecture that organically grows from the site, or architecture that embodies the idea that Louis Sullivan found in Asa Gray’s BOTANY "Seeds are the final product of the flower, to which all its parts and offices are subservient”. Another kind of photograph is appropriate: those which are less independent, more fragmentary, those which reach out beyond the picture frame for suggestions and for space. Especially the contemporary organic architect and his idea of space-time: space-time is best echoed with two or more fragmentary photographs that lock into a whole in the mind of the spectator. (See pages 168, 169.)

In an attempt to minimize this barrier [printed page) to understanding I have restricted my written commentary and re lied primarily on the uninterrupted /10w of visual images, interpretive in their own right, to recreate the particular atmos phere of Japanese architecture.

NORMAN CARVER, JR.

Paired these photographs, which are in themselves fragmentary, form a unit. When experienced one after the other and interlocked in his mind the spectator has a photographic echo of space-time. These two photographs further illustrate Sullivan’s passion to make the exterior an organic outgrowth of the interior.

Does the photo graph show precisely what is there? And does it make a good, an esthetically good, pattern in form and tone? These questions will be answered much more confidently than the other: Is the photographer’s a legitimate presentation of the architect’s or sculptor’s intentions?

NIKOLAUS PEVSNER

CONFLICT

When an architect looks at his building he sees the myth in his mind instead. In this situation the photographer who thinks himself an artist cannot cope as well as one who is clairvoyant.

ARTHUR SIEGEL

ARCHITECTURE AS AN ORGANISM

Ruskin’s discovery in the last century that stones have tongues and building life was one upheaval among many which marked a revival of projecting, by introspective means, the human being into the inanimate. Freud’s introduction of the objective scientific method to romantic introspection was another undulation of this underlying current of anthropomorphism which makes itself felt in many fields today, organic architecture not the least.

For example our determination to identify buildings or city planning with individual architects : compared to the cathedral builders who anonymously raised stones to the glory of God our own collective efforts are crystallized in the architect.

"You mean there is a good piece of architecture for me to look at?” No. I mean, here is a man for you to look at... 1 mean that stone and mortar here spring into life and are no more material and solid things . . . wholesomeness is there, the breath of life is there, and elemental urge is there.

LOUIS SULLIVAN

Never fear. We are all poets. You do not see things now; but, a little later on, things will begin to see you and beckon to you; and you will understand. So, when I tell you that this wretchedly tormented structure, this alleged railway-station, this alleged terminal railway-station, is in the public-be-damned-style, is degenerate and corrupt, 1 repeat to you only what the building says to me.

LOUIS SULLIVAN

Our architects in turn speak of buildings as being alive; the metaphor that a building is born, lives and dies seems natural to us. The architectural historian projecting pastward thinks he can discern the opening, crescendo and decline of groups of buildings or cities and speaks of "periods”, cultures. When we project human qualities into stone and steel and time architecture indeed seems to be an organism with a historical continuity.

The architectural photographers—the fifth generation of them are at work today—have an ambiguous, because shifting, relation to architecture as organism. This is so partly because the objectivity of camera work hides a central indeterminacy and partly because time pertaining to buildings passes differently than time perceived by man. As the life of a cat is to a man, so a man to a building: to a cat a man must always seem to be the same age. Charles Sheeler, painter and photographer, bullseyes the situation when he writes, "Even though I have so profound an admiration for the beauty of Chartres, I realize that it belongs to a culture, a tradition, a people of which I am not a part. I revere this supreme expression without having derived from the source which brought it into being.”

Fredrick Evans, a period or two closer to Chartres than Sheeler, appears in his pictures to agree that for all his rapport he can not return to the source. If this is true a Gasparini can photograph a chapel by Le Corbusier with greater insight than he could a Gothic cathedral because the chapel was "invented” in his own lifetime. Or a Szarkowski can photograph the idea of Louis Sullivan because of the sympathy of a young man for a young architecture, though he never met the man and the buildings are rapidly disappearing.

ANTHROPOMORPHISM:

SUSPICIOUS TO MANY IS CATALYST TO ARTISTS, ARCHITECTS INCLUDED. HENCE THE ARCHITECTURAL PHOTOGRAPHER MUST UNDERSTAND ITS USE-AND USE.

Centuries old is the practice to let fall into ruin those buildings that we have ceased to understand : today we bomb them into basements for taller buildings or bulldoze them into parking lots.

The relation of the architectural photographer to architecture as an organism is also affected by the spirit of the times or period. Fredrick Evans, for all his insight and perception of the significance of the ancient cathedrals, may have to admit that he is bound to see with the same eyes that his contemporaries use. Compare the photographs representative of the style of seeing prevalent a century ago, Frith, Du Campe, the unknown master of the Round House with the contemporaries, Siskind, Carver, Baer. The difference seen is due in part to the influence of the times or period ; part of the difference is ascribable to how a period looks at its heritage. The first generation of photographers recorded the great buildings of Europe with respect and sufficient familiarity to be conscious of feeling. The contemporary generation of photographers records buildings known to be built to last only twenty years. An amazing and organic interchange has happened between photography and architecture in five generations : the great buildings first recorded were made for men not photographs ; today architecture is camera conscious and often new buildings and their sites look as if lifted from the pages of the ARCHITECTURAL RECORD.

Thus do I insidiously prepare the way for the notion that creative architecture is in essence a dramatic art, and an art of eloquence: of subtle rhythmic beauty, power, and tenderness.

LOUIS SULLIVAN

TO PHOTOGRAPH GREAT ARCHITECTURE OR HUMBLE, THE POET IN THE PHOTOGRAPHER MUST BE ACTIVATED -WITH BAD ARCHITECTURE, THE SAINT

The architect is a restless observer. He is always active and eßective in the investigation of Nature. He sees that all forms of Nature are interdependent and arise out of each other, according to the laws of creation. It is the poet in him that is the great quality in him.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT

But he would have warned that man's desire is the most basic of building materials, and that a framework for his psychic needs is the greatest structural problem. For the function of ivhich Sullivan spoke was the spirit in search of substance, fohn had called it the Word.

JOHN SZARKOWSK1

NOW, THIS STONE IS CHRIST

St. Jerome

THE AGONIZING RESPONSIBILITY

The manifestation of poet in the photographer must match the poet in the architect, or the collective poetry of a community of builders, neither more nor less. A great photographer can expand to a soaring essence. He can exceed the spirit of a lesser architect: he will feel the shortcom ings; know that he can supply the lackand be torn. He has in his power the gen erous gift. We can measure his integrity by how far he will let the essence of a build ing make or break his photographs.