CONTROVERSY AND THE CREATIVE CONCEPTS

nancy newhall

Nancy Newhall, biographer, historian of contemporary photography, curator of the Photography Department of the Museum of Modern Art during the war, and since then closely connected to the George Eastman House at Rochester, outlines the men and ideas that are prevalent in photography today. The essay will be published in two parts.

Last fall, in Paris, I found myself involved in hot defense of the ideals and methods of photographers in the West; this spring, in San Francisco, I found myself involved in equally hot defense of the photographers in Paris. Convinced of its own passionate logic, each group refuses to believe the other has any logic at all, and condemns its philosophy, or its subject matter, or its technique, or its motives, or its concepts in toto as full of error and headed for limbo. And then there are the men apart, monolithic on the horizons, whom both extremes misunderstand with irritated affection and respect. In all this there is little animosity; there is bewilderment and concern—WHY do the others stick so stubbornly to ideas so obviously mistaken?

Perhaps it is time that a few of the most controversial concepts were set forth side by side so that they may be seen for what they are—vital, thorough-going principles. Each, for at least its chief protagonist, is a whole way of living and working so as to attain an ideal in photography.

The following is a catalogue of concepts and the men who have generated them; it is not complete. There are others that should be here, and,

I hope, will be here, set forth by their creators and believers who know them better than I; aperture is a forum for the ideas and images of creative photography. Each of the individuals briefly outlined here has opened for many of us a region unknown before. I have tried to set them down as I have seen them; the words I ascribe to them I have heard them say. I have tried to present their concepts from the inside out, with justice and without favoritism.

There is no need for any photographer with a different concept to agree; there is great need to recognize the intensity and integrity of such concepts, and to rejoice that now, in our medium, there are such ardent beliefs and strong individualities. In flaccid periods the work is flaccid too. In spite of its failures, its waste and its unsolved problems, NOW (the 1950’s) is one of the important periods in creative photography. And the force of the emerging future is behind it.

I—THE EUROPEAN PHOTO-JOURNALIST; HENRI CARTIER-BRESSON.

To take Europe first: Europe, as Henry Miller said, is "art-ridden.” Photographers walk humbly between walls weighted with a thousand or two thousand years of overwhelming art—even when they have thrown any rivalry into the gutter and have dedicated themselves to what only photographers can do. Photography in Europe is an eye, a magic eye, an incredible and incontrovertible eye. Delacroix said no man could paint great "machines”—canvases like his—unless he could sketch a man falling from a fourth story window before he hit the ground. European photographers feel they must be faster still: present a totality in an instant, an instant almost beyond the human eye.

Of course there are still in Europe, as Ín America, photographers who emulate painting. Some, as here, follow the Genre and Impressionist styles favored by the older Pictoriaiists; most of them now, since Man Ray and Moholy-Nagy in the 1920’s led the onslaught of the "new vision,” followed the forms of the Abstract and Surrealist movements, making photographs, negative prints, double printing, and so forth. But along with the "new vision,” which hit Europe a little later than America, came a delight in the unique revelations of the camera. Man Ray discovered the strange juxtapositions of reality in the photographs of Atget; Moholy-Nagy discovered the weird shapes and movements seen in trick photographs, scientific photographs, press photographs. At the peace conference Erich Salomon was photographing people, unposed, in dim, available light, using a small camera with a huge aperture lens; with the same approach and type of instrument Alfred Eisenstadt was making informal and moving stories. A new concept grew up and crystallized behind Henri CartierBresson and his uncanny gift of seeing, as someone said, almost on the inner eye.

Cameras and Seeing.

View cameras, and big cameras generally, were regarded as impossibly slow, cumbersome, and conspicuous. Only the 35-millimeter and the twinlens reflex were in repute. Fast and little and light, the new cameras were for seeing; they were for people. Loaded with lengths of inexpensive film, they led to a new way of working. You found your subject and merged as far as possible with its background; if you could, you became invisible. If not, you got accepted, and took photographs until you were forgotten. Then you photographed the developing action until the climax was reached and you achieved the ONE picture out of the whole roll, or even several rolls,which summarized the whole. For this kind of picture-making you must be forever alert. The action happens just once in all time. There is no retake ever. No prearrangement, no direction will ever bring the same unmistakable flash of insight into actuality.

The little cameras became a part of the man using them. I am sure Henri Cartier-Bresson puts on his Leica as automatically as he puts on his shoes.

He is never without it. He carries no parcels ever, so that he may always be instantly ready. At any moment the worn case may appear open; without looking down, without haste, he sets the shutter and the stop. With a slow flow of a hunter anxious not to attract the gaze of his wild game, he raises the camera to his eye, clicks, and as slowly lowers it. No one has noticed so quiet and natural a motion. He seldom uses a light meter. It attracts attention. He has learned to "feel” the light as the old photographers did. He dresses inconspicuously; who would look at a slight fair man in an old raincoat? He can vanish from your side in a street only moderately crowded; you can scan it carefully and not see him. Then, just as suddenly, his camera back under his arm, he reappears smiling, at your elbow. He drinks a little wine, and that liberally doused with water; he lives for the strange revealing flash, the magic moment, and he refuses to miss it because his timing is slowed by wine or anything else. In a busy restaurant he will stand up and sit down again; he has made a portrait of a man at another table. But he loves night, because the houses become transparent; he does not need to vanish, he can just wait and look, and his presence in the shadows will not disturb what is happening within. "Isn’t it marvelous?” he asks with a shining face when what he has seen fills him with affectionate delight and often a wry humor. He characterizes the best French photography as "sharp, dry, and kind,” but his own often goes beyond his definition when his pity or anger is stirred.

His seeing of an apparently unpredictable accident is as precise as that of Weston or Strand with an 8 x 10 and a relatively static subject. He never crops, nor allows editors to do so. He paints to make his sensitivity to plastic forms and values more acute, as well as for the private pleasure painting gives him. Line, tone and form interest him; textures do not, and he scouts the idea held by Americans that a mastery of texture is a sign of maturity.

The Print is a Step Between Seeing and Publication.

The print, to him as to most European photo-journalists, is just a transition between the seeing and the publication. It is something to toss by the dozen into the laps of editors; it is nothing by itself. The one aspect of technique which engrosses Europeans is how to increase speed in photographing indoors or at night. Developing and printing they usually leave to a technician in a laboratory. Enlarging is routine, the technician following the photographer’s indications on the contact sheets. The image—the seeing—is important; the print is not, and to American eyes is execrable— not even half "realized.” The print to a European is only a proof; his image is not complete until reproduced where a million eyes can see it. If his intention then appears clear and forceful, he is content.

When a print is required for exhibition, Cartier-Bresson works directly with the technician, and works for a quality much like that of a good gravure. He chooses semi-matte paper, he enlarges to 11 x 14 or 16 x 20, and insists on tones like those of a wash or charcoal drawing. He wants his image sharp enough to be convincing, but the sharpness Americans find requisite seem to him a fetish, beyond and apart from what is necessary.

For Cartier-Bresson, as to most Europeans, there is just one endless and multiform subject: people, and the places and events they create around themselves. For him, they alone have significance; their gestures light up vistas sometimes exquisite, sometimes amusing, sometimes tragic or appalling. He feels that in his own early works he often paid too much attention to the astounding designs and mysterious appearances created by chance, and he censures others who succumb to such meaningless and egotistical pyrotechnics. The merely pretty horrifies him: "Now, in this moment, this crisis, with the world maybe going to pieces—to photograph a landscape!” He has no doubt of the sincerity or the stature of Weston or Adams or Strand, but, although he feels closer to Weston, they mystify him; looking at their work: "Magnificent! — But I can’t understand these men. It is a world of stone.” To the explanation that through images of what is as familiar to all men as stone, water, grass, cloud, photographers can make visual poetry and express thought beyond translation into other media: "Do they think that by photographing what is eternal they make their work eternal?” To photograph a house instead of the man in it seems to Cartier-Bresson inconsistent, and to find meaning in such images seems to him dangerously personal and close to mysticism. The further idea that, in the American West, man appears trivial and civilization a transient litter: "It is, I think, philosophically unsound.” Man to Europe and to many in the American East, is still the proper study of man. The earth, the universe, eternity?—"They are too big, too far away. What can we do about them?”

Devoted to this European concept of a photographer’s function there are individuals as different from Henri Cartier-Bresson as Bill Brandt, wandering with his Rollei like a pleasant spirit through the nostalgic and romantic byways of Britain, or Brassai, with his immense gusto for the human comedy just as it stands, and his ability to become by osmosis a natural part of any milieu that interests him.

II—THE AMERICAN PHOTO-JOURNALIST.

Beyond question, the concept of photo-journalism dominant in America is that developed at LIFE. That concept is a composite. No one individual produced it; no one photographer is its arch type. The LIFE photographer may have become a type in the popular consciousness—extrovertial, hasty, hung with gadgets—but in actuality such characteristics are common to a wide range of violent and specialized individuals.

Forming the style of LIFE at its inception were photographers as different in approach as Alfred Eisenstadt, bringing his warm and human version of the European concept, Margaret Bourke-White, who had studied with Clarence White, with her magnificent interpretations of industry, and Peter Stackpole who, in photographing with a Leica the building of the Golden

Gate Bridge in San Francisco, tried to combine the brilliant print quality of Group f-64, then at its peak, with the human directness of the Documentarians, then just forming.

Behind the LIFE concept as it evolved was a nation for whom photography and its developing forms has been for a century the most satisfying visual communication. Behind the American photo-journalist there were the battles led by Stieglitz and the Photo-Secession for photography as an art; the journalist inherited a conviction that his medium is important and quite possibly, in the future, second to none. From Stieglitz, Strand, Weston, Adams—the so-called Purists—he acquired standards unmatched elsewhere for precision of technique and intensity of statement, standards that never fail to stagger and upset the European who is required to conform to them. And from the Documentarians—another name that needs re-examination—he absorbed a sense of dedication to coming to grips with whatever was before him; from Walker Evans, an approach to architecture, from Dorothea Lange, an approach to people.

For the American photo-journalist, what he does is no sketch of such actualities as happen to be beyond human eye and hand; it is the total presentation. And probably the most important presentation, not only to the present but to the future. He feels a duty to the idea or the people he photographs, to the men and women who will see his interpretation now, and to history. He resents any falsification or distortion of what he tries to interpret. His work is heavier and more complete than that of his European colleague; the grace and wit that help Europe to put up with history are not yet his concern, nor his country’s.

The concept developed at LIFE centers about the subject and how it may best be interpreted. When there is time, the photographer who in the editor’s opinion is best suited to the assignment is sent forth; when there is an emergency, any photographer who happens to be nearest, no matter what his specialty, is expected to handle it capably.

The American is much more versatile than his European colleague. He rarely limits himself to one camera, because that implies limitation of subject matter. He will use a miniature with the fastest known lens, load it with the most sensitive film made, and instruct the lab to use special developing techniques, when he is working with people in available light. The next night he may string up a hundred flash bulbs down some vast dark area and make a carefully calculated exposure with a view camera. And be out before dawn the next morning with color on his mind. He will use all cameras, all techniques, all gadgets known to him in order to present his subject properly.

He is a much better technician than the European. The exigencies of time, space, and publication impose laboratories and technicians upon him. He insists on the finest possible processing; he is grateful that the burden of that inevitable disappearance into the darkroom is lifted from him. But he still feels frustrated, resentful, and a little guilty when he does not lift his own negatives out of the hypo, make his own choice and print it himself. When he does make a print for exhibition, it is a good print, if not a great one by American standards.

But the contact sheets and the enlargements are still dumped wholesale into the editor’s lap. The selection, the layout and the slant given to the story are still the editor’s. The photographer may provide the most dynamic reason for the magazine’s existence; he may get a salary in the upper brackets, but he is trusted only as a kind of remote control eye. Individually and collectively the photo-journalists complain about this, and gradually they make progress.

Like advertising and fashion photographers, the journalist gets sick of the endless stuff he spins out of himself on celluloid and more sick of fast and superficial coverage on assignments he does not have time to penetrate and absorb. Special privilege is pleasant and so are large expense accounts; the drive, the pace and the contact with strange people and vivid places is exciting. But the life of the journalist is a life without roots, without family, except as glimpsed, married and begotten between assignments. A life in constant motion, at top speed, in which he is forever both the hunter and the hunted. A life in which a man can soon be worn out, burned out, and bored out, even when he is thoroughly aware of the occupational hazard.

The American photo-journalist is not particularly bothered by painters; the great gage that lies dimly or strongly on his consciousness is that of the great Purist photographers. He may not agree with them any more, he may feel they are limited or misled, but by God they did—and do— what they believe in to the utmost that is in them, and they live—somehow —and die still creators. He plans to save so that he can stop next year and do his own work; he plans to take half the year off; he announces he will take only assignments he believes in. If he is powerful and indispensable, he may get the magazine to sponsor his personal projects. Magnificent essays have been born of this approach, and through them a new concept of the photo-journalist’s stature and function can be seen emerging; the photo-journalist as creator, planning and directing his projects, and assuming ultimate responsibility for his interpretation. Towards this new concept many leading photographers are working, including individuals as diverse as Eliot Elisofon, indefatigable explorer of primitive cultures and of the potentials of color, and W. Eugene Smith, whose identification with his themes is so intense that he and we become participants as present and unseen as the wallpaper or a shadow in the street.

III—EDWARD WESTON.

Photography can get infuriatingly complex; entangled in wires and batteries, in straps and cases, in miles of celluloid, and fragile mechanisms persistently a little out of kilter, the photographer has moments when he feels like Laocoon. Living can be another endless coping with illusions of leisure, and to any American photographer reflecting on the entanglements he endures in order to earn further entanglements, there is apt to occur the image of a quiet little man named Edward Weston.

A little man from whom there issued, as from a volcano, immense forms and concepts. A little man with a big camera and a bare simplicity in his living and working. In the Twentieth Century, Weston is as startling an apparition as he is logical. And of all the challenges that haunt the conscience of the creative American photographer, Weston’s lies perhaps the most uneasily.

From the moment when, at fourteen, Weston was given a box camera he lived for the hours when he could be alone with his camera. It was his companion in delight, and if he could have earned his living thus, he would have been content. But no creative photographer can, as yet, live by the sale of his personal work. Any passable painter does, but in photography men with the stature of a Picasso or a Roualt get so meagre a return that they must depend on something else for a livelihood.

Weston chose portraiture, because he would then at least own the tools he needed. Press, journalistic, fashion and advertising photography were all embryonic around 1910, but if they had been full grown Weston would probably still not have chosen them. He was active; he chafed at being tied to a studio, all day; he loved expeditions with his camera. But the core of his being was meditative and apart; he rose early to be alone and pour forth in his daybook the molten stuff inside. He was not a man who liked to be hired. Something in him broke even his own harnesses. He had wanted a home; he welcomed each of his four sons. In portraiture he achieved a decent living and high professional and salon honors. But increasingly he hated pandering to human vanity; increasingly he hated dodges and respectable false fronts; increasingly he desired the time and energy to create. He was sick of illusions, even his own. Perhaps especially his own grand gestures as an artistic personality. At thirty, when most men who have made an early success settle in, Weston began to grow.

It wasn’t easy; probably it has never been easy. Nor were the sacrifices necessary all his own. But he felt that without the integrity and power creative photography gave him, he would have nothing to give to anyone.

The Years of Decision.

During the years of his growth, he was alone. There was then no other photographer on the West Coast with the same concern in creation. Rumors of Stieglitz in New York reached him, and articles about Stieglitz helped him think, but a few hours with Stieglitz, during a brief journey East, seemed merely to confirm what he already knew. What, for Edward Weston, lay beyond, he would have to find for himself. And what lay beyond was difficult to define. He worked towards it through the sudden flashes of vision and the unreasoning responses every photographer knows. The acute senses of his friends among the painters and writers probably helped him most; in his daybook he meditated on their comments as he reviewed his new work.

An instinct for the simple and vital, and a disgust for artificiality and waste helped him both in his work and his living. Yet so strong is tradition and so slow is growth it took him years to husk away old habits of thought and get down to his clear concept. He fought his way through impressionism, through haze, soft focus, papery surfaces; through the arty arrangements and fragmentary angle shots of the cubist fringe.

Artificial light he discarded as a nuisance and a crudity; the subtleties of natural light engrossed him. More and more he found himself using his enlarger only for his portrait work; a diffuse enlargement, he found, was the simplest way to avoid horrifying his sitters by their own faces. His own work he printed by contact. More and more he wanted nothing— no tone, no tactility of surface, not even the impress of himself—between him and the sharp forms and textures of reality. But reality for him was not the ordinary peeling of a picture from an object. He came to realize that what moved him most was form—the unseen forms hidden in the commonplace, forms of force, growth, tension, erosion. He found them in smoke stacks, in rocks and faces, in shells and vegetables; he saw them in a cloud, a hill, a naked body, a wave, a tree. "How little subject matter counts!” he wrote. A nude back like a pear, a cypress root like a livid flame, feathers in the wing of a dead pelican seen as barbs of light in a dark sky, a stone like lace—he discovered them with amazement.

He found that, for him, everything—his life, his work—was a matter of dynamics and of focus. Now and then he sold enough prints to dream, fleetingly, of being free from portraiture—"If only I could live by the sale of my personal work!” But since he could not—and for only three and a half years out of nearly fifty did he achieve freedom—he determined to be as free as possible. If he eliminated everything unessential, everything that cost too much in cash, time and energy, then he would not have to earn it; more hours of daylight would be his and more strength to create with. His thinking went much like that of Thoreau: a hunk of excellent cheese costs little and can be eaten in the hand, but a poor steak costs a lot and besides you have to cook it and clean up afterwards. He evolved a housekeeping simple as an Arab’s; no cookery during daylight except a pot or two of superb coffee.

The Technique.

His technique was equally bare and vital. An 8 x 10 view camera for his personal work; a 4 x 5 Graflex for people. Negatives developed in a tray, in pyro, by inspection. Contact prints, on glossy paper, made under a frosted bulb hung overhead to facilitate any necessary dodging. A drymounting press and a stack of smooth white mounts. That was all. The classic and ancient tools of his trade, essentially the same during the century of photography’s existence, were what he chose as the most potent and flexible. He made some of his best early things with an old Rapid Rectilinear he picked up for five dollars; later he had fine new lenses, but, as he said, when people remarked that he must have a marvelous lens, "Good photographs, like anything else, are made with one’s brains.” His use of a light meter—urged on him by friends—was also independent; he used it all over the sphere of vision to help him in what he had done so many years — "feel the light.” Then, after adding everything up, he usually doubled the result; he likes a massive exposure. And natural light only. He used it to do extraordinary things—full sun for a body outlined by shadow or for a head seen against the sky or the black of an open door; foglight for his huge sculptural forms; skylight for his sitters as they moved and talked, sitting in some old chair, in front of his waiting lens. He even got to the point in his professional work where he could hang out a sign UNRETOUCHED PORTRAITS and get away with it. He had really learned to see. Props and devices were quite unnecessary.

He could never wait to develop a batch of exciting new negatives. Printing was something else; the day before was spent in scrupulous cleansing, organizing, mixing; this is true of all major American photographers; for Americans, the print is the test of both negative and photographer. For Weston, there was a special emphasis: in his early years, he had seldom been able to afford more than one sheet of expensive platinum or palladio paper for his own work and he had had to learn to gauge his exposure so accurately that the first full sheet, or at most the second, was worth exhibiting.

You don’t toss prints like this wholesale into the laps of any audience. Weston, like most creative Americans, keeps his prints with tissues between them, to protect the delicate surfaces from abrasion. He shows them one by one, on their immaculate white mounts, on an easel, under the skylight by day, under a photoflood by night. He has learned that twenty to twenty-five prints are about all the sensitive spectator can see with his full intensity—a far cry from the hundred or so expected from the photojournalist by an editor and shuffled through in five minutes.

Mass Production Seeing.

Yet in actuality Weston has evolved, and proved to his own satisfaction, by his own example and that of others, notably Ansel Adams, the theory that photography is the medium above all others for "mass-production seeing.” The painter, in Weston’s opinion, is slowed by his hand. In the course of a long lifetime, the painter can realize only a fraction of what he conceives. For the photographer, conception and execution can be and usually are almost simultaneous, and sometimes so fast that they go beyond conscious thought. At the present moment—in the summer of 1953 —Weston is engaged in trying to make a great and lasting demonstration of this idea: with the help of his son, Brett, he is printing the thousand negatives he considers the best. There will be eight prints from each; from albums, museums, collectors and individuals can choose and order by negative number what they wish. Probably no more startling idea was ever proposed to museums, traditionally conditioned to the small output of painters and the high cost of even a slight sketch. For the price of one so-so contemporary piece of painting or sculpture, the entire masterwork of one of the greatest photographers is for sale. And for less than a bad watercolor or scratchy etching, the massive and sculptural images of a man who could write, with a laugh, "The painters have no copyright on modern art!” And who again,when somebody wrote an article about him titled, "Edward Weston, Artist,” circled the "artist” with a heavy pencil and wrote, "Delete, or change to 'photographer,’ of which title I am very proud.”

Purism.

Nevertheless, Weston was annoyed when, thanks to some dramatic statements he published, and to the spectacular crusade of Group f-64, of which, with Ansel Adams and Willard Van Dyke, he was a founder, he found himself in a niche labelled the Great Purist. He refused to be shackled even by his own hard-won concept, the subjects he had made his own, or the dismay of his friends. He reserved for himself the right to "print on a doormat if I feel I can make a better print that way.”

One tenet held by Purists is never to touch or arrange; Weston had always arranged his shells and peppers, and now he composed satires out of people and objects. Threatening to return to soft focus, he took the idylls so often attempted by the Pictorialists and did them with enormous mastery. At the last of his hours with his camera, before Parkinson’s disease made seeing and coordinating too difficult, he was tackling with pleasure a new kind of vision for him—color. And in black-and-white, he was pursuing his huge forms through their disintegration and their sinking back into the matrix of the earth.

Interpretations and the Wilderness.

Freudian interpretations of his work infuriate Weston. If the same forms recur throughout creation, and people can see in them no more than sexual symbols, he feels that is a pathetic and possibly pathological reflection of the people. And like other Western photographers, he has been accused of theatricality—a charge any good Westerner whether born or made (Weston was born in Chicago) puts down to pure envy. For in judging the work of the West, facts unfamiliar to the East and to Europe must be taken into account, and the basic fact is wilderness. In the West there are immense distances where any track of man is either invisible or ridiculous. The oldest civilizations on this continent are there, in the Indian pueblos and the Spanish foundations; so are some of the most advanced manifestations of the newest civilization. None of them seem more than trivial and transient in the face of the vast spaces and the stark and monumental forms of the earth. The proper study of man in the West is the powers and functions of the earth, and how he may live with them during his brief tenancy. This is the philosophy reflected in Weston’s photographs; that in man, as in the rest of nature, the same forces are at work. With amazement, with humility and a sense of unlimited resource Weston pursues them through the strange beauty of their endless metamorphoses.

Weston is probably the most tolerant of the major photographers; he expects no one to follow his personal concept, knowing that every creator makes his own concept as inevitably as a river makes its own course to the sea. His recognition of the electric quality of achievement in others is instant and generous, no matter how different from his own. But few of Weston’s followers follow him in this, and most of them recoil at the slightest deviation away from the concept. They cannot see an image that is not printed on cool and glossy paper; enlargement distresses them. A blur or a patch of soft focus is like a speck in the eye. A miniature camera is a toy, and its results miniscule, inconsequential and a nuisance to look at. People seldom interest the Weston followers as subjects, apart from an occasional portrait. And they would rather earn their living as carpenters or masons than turn their cameras on what does not interest them and sully their delight for mere cash. Yet with the majority of them, this rigidity is a temporary phase; they emerge with a strong discipline from the silent dominance of Weston’s vision, and begin to evolve their own approaches. For themselves, there may be fallacies and limitations in his concept, but it still stands monumental in its simplicity, a challenge and a catalyst.

(To Be Continued)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Letters From France And Italy

Fall 1953 By Paul Strand -

Criticism

Fall 1953 By Minor White -

Notes & News

Notes & NewsThe Graphic History Society Of America

Fall 1953 -

Has Photography Gone Too Far?

Fall 1953 By James Thurber -

The Search For A Story To Tell

Fall 1953 By Elizabeth Bowen -

Editorial

EditorialThe Creative Approach

Fall 1953 By M W

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Nancy Newhall

-

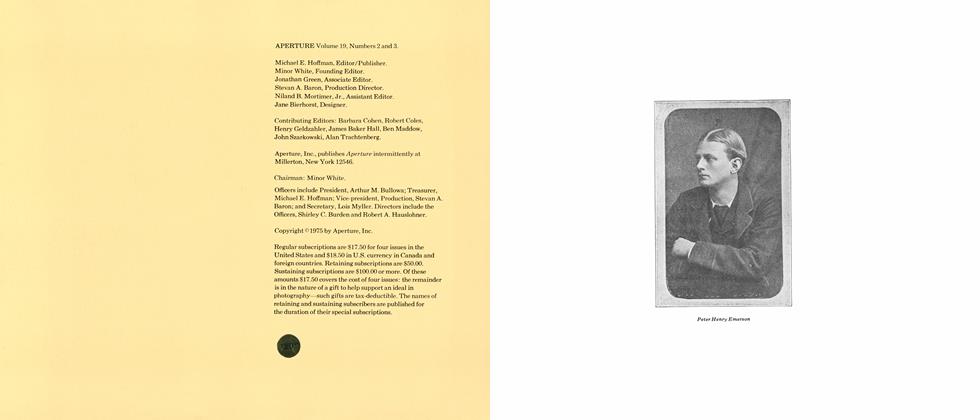

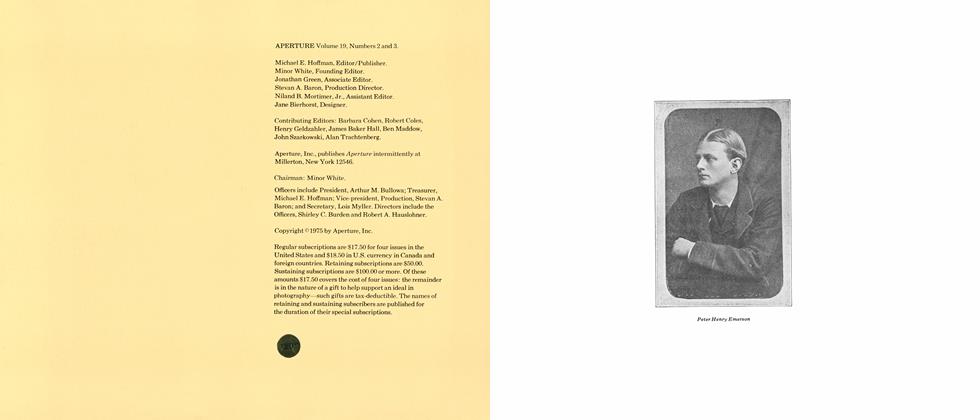

P. H. Emerson

Spring 1975 By Nancy Newhall -

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine Art

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine ArtII. Mr. Robinson’s Tea Party

Spring 1975 By Nancy Newhall -

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine Art

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine ArtVII. "Truth To Nature"

Spring 1975 By Nancy Newhall -

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine Art

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine ArtXIII. "The Death Of Naturalistic Photography"

Spring 1975 By Nancy Newhall -

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine Art

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine ArtAfterlife 2. Oblivion And The Strumpet

Spring 1975 By Nancy Newhall -

Part Two P. H. Emerson: His Photographs Accompanied By Excerpts From His Albums And Naturalistic Photography

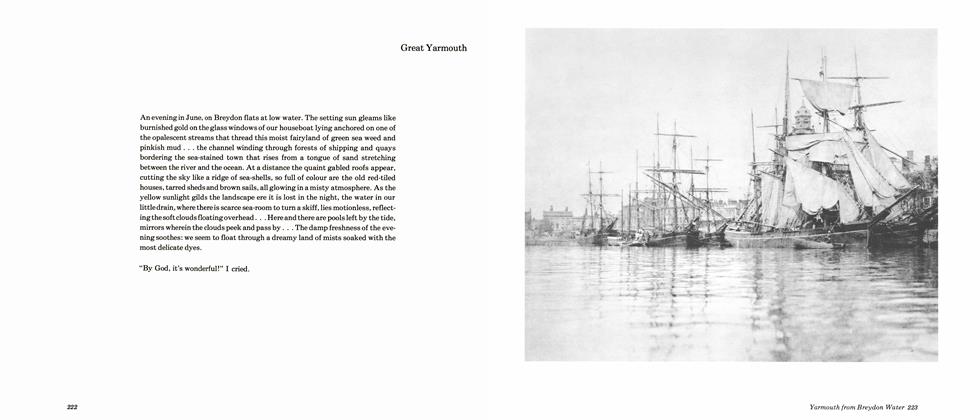

Part Two P. H. Emerson: His Photographs Accompanied By Excerpts From His Albums And Naturalistic PhotographyGreat Yarmouth

Spring 1975 By Nancy Newhall

Nancy Newhall

-

P. H. Emerson

Spring 1975 By Nancy Newhall -

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine Art

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine ArtII. Mr. Robinson’s Tea Party

Spring 1975 By Nancy Newhall -

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine Art

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine ArtVII. "Truth To Nature"

Spring 1975 By Nancy Newhall