nancy newhall / THE CAPTION

THE MUTUAL RELATION OF WORDS / PHOTOGRAPHS

nancy newhall

Perhaps the old literacy of words is dying and a new literacy of images is being born. Perhaps the printed page will disappear and even our records be kept in images and sounds. Perhaps the new photograph-writing — so new we have no word for it — is a transition form, and perhaps, instead, it is, in embryo and by virtue of principles now being discovered and applied, the form through which we shall speak to each other, in many succeeding phases of photography, for a thousand years or more.

We are not yet taught to read photographs as we read words. Only a few thousands, among our hundreds of millions, have trained themselves like photographers and editors to read a photograph in its multi-layered significance. Yet more and more photographers have discovered that the pow'er of the photograph springs from a deeper source than w'ords — the same deep source as music. At birth we begin to discover that shapes, sounds, lights and textures have meaning. Long before w'e learn to talk, sounds and images form the w'orld we live in. All our lives that world is more immediate than w'ords and difficult to articulate. Photography, reflecting those images with uncanny accuracy, evokes their associations and our instant conviction. The art of the photographer lies in using those connotations, as a poet uses the connotations of words and a musician the tonal connotations of sounds.

The number of those for whom really great photographs speak a language beyond words is steadily increasing. But most of us still need verbal crutches to see with. And the most explicit photograph may not reveal to the most omniscient eye of editor or historian the precise place and day it w'as made. Therefore the association of w'ords and photographs has grow n to a medium with immense influence on what we think, and, in the new photograph-w'riting, the most significant development so far is in the "caption.”

What is a caption? The word itself is old, but in its new photographic usage it is so new' it has not yet reached the dictionaries. (In the old newspaper glossary, the caption w'as the headline or title over a picture and wffiat we now call the caption was known — with a pungency captionwriters will appreciate — as the cutline.)

How does caption differ from title and from text? How does it function with them? How does it influence the photograph, and what are its common contemporary forms and its future potentials?

Let us begin with what everybody knows, and propose that something like the following be added to the usages listed in the dictionary:

Title: (Photographic usage, in the United States): an identification, stating of whom or what, where and when a photograph was made. A title is static. It has no significance apart from its photograph.

Caption: briefly stated information, usually occupying no more than four short lines, which accompanies a photograph, adds to our understanding of the image, and often influences what we think of it.

A caption is dynamic; it develops title information into why and how along a line of action. It makes use of the connotations of words to reinforce the connotations of the photograph. It loses half of its significance when divorced from its photograph.

Text: main literary statement accompanying a series of photographs, usually presenting information about the theme and its background not contained in photographs and captions.

Text, no matter how closely related to the photographs, is a complete and independent statement of words.

There appear to be four main forms of rhe caption. There is the Enigmatic Caption, a catchphrase torn from the text and placed under a single photograph. The sequence of interest runs like this: the eye is caught by the photograph, then by the caption, and then the irritated owner of the eye finds himself, hook, line, and sinker, compelled to turn back to the attached article and read it. This type is found in full classic purity in Time.

Then there is the Caption as Miniature Essay. This again usually accompanies a single photograph and comprises with it a complete and independent unit. Life’s "Picture of the Week" and "What’s in a Photograph?” series offer examples, and a glance at any Illustrated London News will provide dozens more. (It is probably the most ancient form of caption; it has survived since the monumental bas-reliefs of Babylon and the wall-paintings of Egypt.)

The NARRATIVE CAPTION is, of course, overwhelmingly the common contemporary form and is familiar to everybody through magazine journalism. It directs attention into the photograph, usually beginning with a colorful phrase in boldface type, then narrating what goes on in the photograph, and ending with the commentary. In a photo-story, it acts as bridge between text and photograph.

The ADDITIVE CAPTION appears to be the newest form, risen into prominence to answer a new need. It does not state or narrate some aspect of the photograph; it leaps over facts and adds a new dimension. It combines its own connotations with those in the photograph to produce a new image in the mind of the spectator — sometimes an image totally unexpected and unforeseen, which exists in neither words nor photographs but only in their juxtaposition. A fine early example occurs in La Revolution Surréaliste; the photograph shows three men bending to look down an open manhole and the caption reads: The Other Room. Indeed, the Additive Caption may be one of the many rare and fantastic forms those intrepid explorers, the Surrealists, domesticated for the rest of us.

Recent domesticated and photographic examples can be found in the late flood of "zoo” books, wherein snatches of ordinary conversation transform photographs of animals into acute burlesques of human behavior, and in Philip Halsman’s wildly successful The Frenchman, where between the printed questions and the photographs of one man’s facial expressions surprising answers come to mind. The Additive Caption already has performed what seemed the impossible: giving a means of applying the light touch of wit and the penetration of humor to a medium as essentially tragic as what it reflects and which records the unconscious pathos of an attempt to be funny as it records the humor in deep tragedy.

The first two forms, the Enigmatic Caption and the Caption as Essay, are more literary than visual in their aims and techniques. The Narrative and Additive Captions, however, involve a host of problems in the new language of photo-writing.

THE NARRATIVE CAPTION belongs to journalism, and journalism is a collective art. Editor, writer, photographer, researcher, art director, publisher, and, to a surprising degree, the public, are all involved in the production of a single photo-story. Who should ivrite what how? is the crucial question. For the caption does influence the photograph. John R. Whiting, in his Photography Is a Language, ( 1 946), pointed out that, "It is the caption that keeps you moving from one picture to another. It is very often the caption you remember when you think you are telling someone about a picture in a magazine.” The caption can call our attention to one detail and cause us to ignore others. It can be so slanted that different captions can cause us to feel rage, tenderness, amusement or disgust towards one and the same photograph. We all remember how photographs from the files of the Farm Security Administration, made to arouse our active sympathy towards a huge tragedy happening among us, were slanted by the Nazis to convince Europeans that all Americans were or would be as destitute as the Okies. Again, where the public itself has been slanted, the caption also takes on a different meaning. The Communists lifted from the pages of Life a photo story about a race riot where the text honestly expressed the indignation felt by the majority of Americans. Reprinted, with scrupulously literal translations, it became to foreign eyes a damning proof of our much advertised fine-speaking and evil-doing.

The basic trouble about captions, according to editors and writers, starts with the photographer. His aim is to get a photograph so expressive no words are necessary. Indeed, the editors and writers suspect, he regards words as a nuisance. Take the news photographer, for example. After rushing to drama or catastrophe (or having it happen to him on a routine job), after pushing, persuading, performing acrobatics of body and brain until he somehow manages to sum the situation up in a single picture, or at least squeeze out a poignant angle of it, then rushing back to develop and in five minutes get a dry print on the editor’s desk, the photographer feels he has accomplished a minor miracle and is entitled to at least a cup of coffee and a hamburger. He should now sit down and peck out the essential data on a typewriter? What are the rest of you guys hired for — decoration?

Spot news is spot news; drama and disaster break forth anytime, anywhere, uncontrollable and usually unpredictable. The nearest staff photographer will always have to jump and the responsible staff reporter or editor will have to do what he can. But a fury of haste has descended even on magazines which never handle spot news and which, allowing for major fluctuations in public opinion, might plan nine-tenths of each issue more than a year in advance.

The magazine photographer also has his woes. There is the frantic story conference with the editor, not infrequently by transcontinental or transoceanic telephone, inciting you to photograph a story of terrific importance. By superhuman effort you get it — then more recent events crowd it into a back page or two, or throw it outright into the morgue. There is the story which you personally believe to be absolutely essential to the world’s understanding, which, either by editorial whim or publisher’s policy, or merely by poor layout and inadequate captions, gets distorted or emasculated.

On a more humble level, there is the new staff researcher, just out of school, whose ideas for stories are as impossible to the camera as to the gorge of the average citizen. There is the "name” writer who arrives before or after you do, when the situation you are working on together has changed, so that photographs and story don’t jibe. There is the caption writer who calls you up an hour before your plane leaves for Africa for more details on a story you did on a biscuit factory a year ago. There is the caption material you peck out in mad split seconds in madder places, which arouses yells of "inadequate.”

There is the business of becoming what Henri Cartier-Bresson once called a "silkworm” — of endlessly loading, exposing, and unloding him, of writing data, of loading the lot on a plane for New York, and not knowing until you are three weeks and two thousand miles away from the subject whether the second strobe went off. And, finally, there is the magnificent oncc-in-a-lifetimc shot, developed and printed by the magazine’s laboratory on a contact sheet with seven others, seen by an editor in a hurry, cropped to its detriment, and used as a visual footnote.

Turning the above recital inside out, the trouble a photographer can cause an editor or writer concerned with text and captions may be clearly seen. First, catch your photographer. If you succeed, try to get his sympathetic ear about your need for more words.

But the editor or writer has his own peculiar woes. According to AÍ Hine, whose "Look, Jack, I’m Busy,” appeared in December, 195 3, in the American Society of Magazine Photographers Netes:

In the first place ... he (the writer) is engaged in fighting a rear-guard action in defence of literacy and the written word. Second, he is not infrequently entangled with his superiors over both the function and the format of the caption itself. Third, he is subject to continuous terrorism, flank attacks, surprise raids and nerve warfare from photographers who consider getting any more information than "somewhere around Biloxi" an asinine imposition by chair-bound freaks . . .

. . . the caption turns into a headlinish appendage of the picture, instead of an editorial unit designed both to help the photograph and be helped by it. Our hero, who, if he is conscientious, may spend some time working out a proper caption scheme for a picture or picture sequence, suddenly finds that his importance has become that of a display typographer. The integrated captions of his series are forcefully replaced by punchier, shorter, bold-type legends, lending themselves to such comic-created sure-fire words as WHAMM! WHOOSH! ZOWIE! and the like . . .

Fighting our editor alongside these forces is the type of art direction which lays out a page with admirable attention to visual beauty, attention so admirable, in fact, that no space is left to explain what the photographs represent. Or which, due to arbitrary values of photo display, gives the caption writer a space of sixty-four characters in which to list the names of six people and describe the function they are attending, and then allows a space of 960 characters to caption a photograph for which, perhaps, the simple legend "Dawn" would be more than sufficient.

For your best caption writer is by no means always a fighter for more caption space. Rather his interest is in fitting the best caption to each picture, and since this may sometimes mean four lines for one photograph and two words or none for another, his pleas become the despair of the tidy mind of the art director. Particularly of the art director who follows the well-nigh universal trend of demanding that all captions fit precisely flush into box-like squares or rectangles.

Needless to say, the art director is convinced the others are bent on the destruction of their own best interests as well as his best ideas, and the researcher knows that he is the forgotten man or woman.

Small wonder that most photostories emerge with the marks of this brutal confusion still upon them. The miracle happens when out of this minor hell a really great photostory is born. On one such as W Eugene Smith’s "Nurse Midwife,” (Life, December 3, 1951), the photographs, words, and layout seem natural and inevitable to each other. The photographs are so intense that the photographer and his means of photographing have become invisible. The words are so sensitive an extension of the photographs, and the layout so clear and quiet that we ourselves are there, looking with our own eyes and hearts upon these people.

Another extraordinarily poignant series by Smith, his "Spanish Village,” was published by Life in four different forms, and a comparison between them illuminates certain aspects of the value and functions of captions. The first presentation was five spreads (10 pages) in Life, April 9, 1951; the layout had space and the text and captions were kept sharp and quiet to let the photographs speak. Then Life brought out, as a prestige item, eight more reproductions from the one hundred and fifty photographs Smith had made, and published them in a folder with text on the inside cover, but with neither titles nor captions. Compare these eight, which were not used in the first publication, with those which were and a strange fact leaps forth: those first selected were generally incomplete without captions whereas the eight needed neither titles nor captions. Here new light is cast on the photo-journalist’s ancient sob that his best stuff is seldom if ever used. Yet of those I have seen, the three greatest did appear in that first presentation; the Guardia Civil received a dominant position in a spread, the Threadmaker became a kind of major footnote, the Mourners for the Dead Villager was given a full spread. Then the Mourners appeared as a subject for a "What’s in a Picture” caption essay; sincerely the writer tried to extend our participation in the photograph— and still the photograph spoke more strongly than the words. Finally, in the Memorable Life Photographs exhibition, all three of the dominant photographs were shown, with bare titles. And here the Threadmaker could be seen in its full stature, at once a village woman at work and an image haunting and eternal as a drawing by Michelangelo of one of the Three Fates.

The main conclusion to be drawn from these comparisons seems to be that a great photograph outlives any w'ords that may from time to time be attached to it, just as a great book outlives many attemps to illustrate it.

To make "Spanish Village” Smith read long and looked long before opening his cameras. In other words, he worked like an artist and a professional. If the trouble with photo-journalism actually does begin with the photographer, then the solution seems obvious: make the photographer solve it. While photographing, he has within hand’s reach the raw material needed for text and captions. He knows the situation from both inside and outside, because he has to be both in order to photograph. Often he has a vivid, if immature and untrained, sense of words, and the spontaneous phrases embedded in the chaos of his notes express an experience more succinctly than the best deliberations of a writer remote from the event. No one is more concerned about his work than the photographer; until he sees his negatives and prints them, he feels half blind. Why not make him responsible for the whole photo-story in its preliminary state? Give him the time to conceive and realize his job completely. Let him sketch out what is to happen on the pages allotted to his subject. Then editor, writer, and art director will have an integrated whole, however raw, to polish and perfect, instead of a jigsaw puzzle to initiate and assemble.

Just suggest this to an editor, even the most sympathetic, and the chances are he will turn to you in shocked surprise. The photographer??? Responsible for text? Why, an editor, so editors say, thanks God when he finds a photographer with intelligence enough to cover a story and bring back photographs of it, let alone one who can put two words together without falling over them. The photographer responsible for picking out his own best work, as other professional artists do? Why, the photographer, in the editor’s opinion, has ridiculous attachments, generally either technical or sentimental, to the least interesting pictures. His ideal layout is one photograph to a page or even to a spread, either bled or with an acre of white paper around it. (And his most brilliant suggestion for magazine makeup is usually that a whole issue or at least a half be devoted to his latest story — no captions; the pictures don’t need any. Just a short introduction about the subject and how he managed to photograph it.)

Well, what is wrong with photographers that this libel is uncomfortably true? Are we people with a profession to measure up to, or are we a set of mechanical eyes unfortunately attached to egos?

Let us not lose sight of the editor, however. As the conductor of this mad orchestra, assembling the photostory and fitting it to the printed page is his job and his form of expression. Perhaps he enjoys the power of x-ing out sheaves of contact prints, greening the captions, reslanting the text, recasting the layout. Perhaps he likes the battering of a multitude of deadlines. Yet the real power and joy of his job lies in developing his human and physical material and orchestrating it into a balanced scheme and program. Often the original idea for a story is his, and his the inspiration that gives impact to its final presentation. He fits the job to the man, he helps the photographer realize his individual gifts. The young medium itself, huge as it is, opens up because of his sensitivity to its needs. In giving the photographer the challenge of full responsibility for his job, the editor helps the medium expand and himself to eliminate a source of frenzy.

This matter of the photographer’s resistance to words, however, deserves further examination. Few good photographers are without it; it seems almost instinctive with them. Stieglitz, for example, never permitted so much as a title to appear with its photograph. Actually, the photographer objects to words only when they distract from or duplicate what is said in the photograph. We have already stated that to photographers, and a growing number of others, certain photographs need no words because they speak a more immediate language.

THE ADDITIVE CAPTION

What kind of photograph, then, needs a caption?

Obviously, one that is in the general as well as the specific sense documentary, where the photographer is primarily an eye witness and secondarily a creator. Where the photograph completely expresses its subject, it scarcely needs a title. Where it transcends its subject, words of any kind become slightly absurd. Such photographs, of course, occur in every one of the manifold branches of photography, from snapshot to scientific. Sometimes they are pure accident. More often they represent a culmination of actuality and personality. When enough photographs whose power can be ascribed neither to chance or fact emanate from one man, we call him a creative photographer; he has mastered the medium.

What happens, then, when the caption, or title, is omitted?

Howls of dismay go up from those who feel lost without their verbal crutches or who are too impatient to read anything longer than a caption. In making Time in New England, (1950), Paul Strand and I were working out an additive use of text and photographs. Deliberately we confined the titles, which were only handles for reference anyway, to the table of contents in the front of the book. One reader carried his protest against this system so far as to write every title under its photograph — until he discovered that the page numbers were in the table of contents too.

David Douglas Duncan omitted even titles from This Is War! and raised a storm of criticism. Those who grumbled at no title for a Strand were outraged to lind no identification whatsoever in a whole bookful of "journalistic” photographs of the war in Korea. À lodern Photography leaped to Duncan’s defense, asking, in effect, "Why don’t you want to read about these pictures, read what the photographer has written about them in the book?” Duncan, whose purpose was to describe what war is, rather than the fluctuations of one campaign, wrote from Tokyo:

. . . your review is the first, among the magazines, which tries to understand ... as you pointed out, it makes no difference whether it is one hill, or another; this bend in the road, or that; one man, or his brother. It is every man who ever carried weapons in actual line combat . . . the combat of no glory. ... It is a story, and as such one must read it all the way through. It's strange, you know, but I thought it was so obvious!

Which points out the curious divided state of our literacy at present. Some of us, even professional critics, will not read and neither will we look for ourselves. In watching people look at Time in New England, I observed that the visually-minded skipped from photograph to photograph throughout, then went back to the text, while the word-minded skipped through the text, completely ignoring the photographs. Those who read both as they came, for whom one medium was as clear as the other, and who could follow the sequence as it was made, were rare. Yet reading the two mediums so that they coalesce into one is difficult at first only because the form is unfamiliar; as in listening to strange music, the strangeness soon disappears, leaving only the music.

Wright Morris, in his first book, The Inhabitants, (1946), eliminated titles, wrote verbal equivalents for his photographs and tried to tie them together with a thread of narrative in caption form. The book received the critical acclaim the first book genuinely created in two mediums by one man deserved, but it stands as a valiant rather than a successful attempt to weld the two into one. Time and intensity are as much to be reckoned The touch of invisible things is in snow, the lightest, tenderest of all material. I have lain in the calm deep of woods with my face to the snowflakes falling like the touch of fingertips upon my eyes.

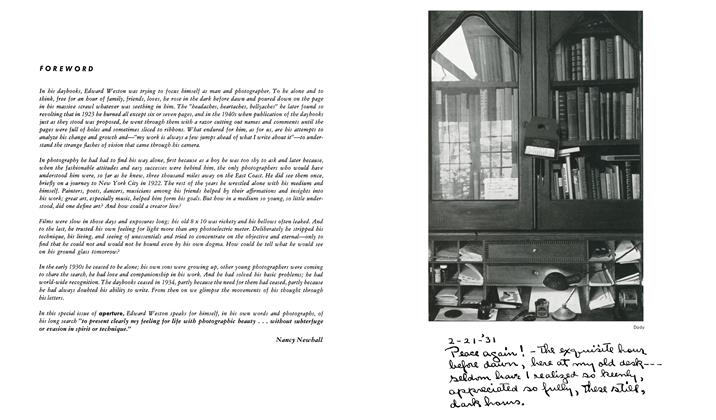

A sample page of Ansel Adams’ illustrated edition of lohn Muir's Yosemite and the Sierra Nevada, (1948), is reproduced on pages 26 and 21. The Additive Caption serves a dual purpose. Phrases from the text, which is presented by itself in the first half of the book, appear opposite each photograph in the last half of the book. These phrases recall the text and accentuate the mood of the photograph.

29. Fresh snowfall, Yosemite Fall and orchard.

with in a book as a film; you cannot remember a thread of narrative when you have a photograph to understand, a condensed paragraph or two to read, and the relation between them to consider before you turn the page to pick up the next wisp of narrative. In his second book. The Homeplace, (1948), Morris wrote a consecutive novel wherein the action in the text, which appeared on the left, seemed concerned with the images appearing on the right. The caption form he eliminated completely.

In the Additive Caption, the basic principle is the independence — and interdependence — of the two mediums. The words do not parrot what the photographs say, the photographs are not illustrations. They are recognized as having their own force. Archibald MacLeish felt this when he wrote of his Land of the Free, (1938), that it was

a book of photographs illustrated by a poem. . . . The original purpose had been to write some sort of text to which these photographs might serve as commentary. But so great was the power and stubborn inward livingness of these vivid American documents that the result was a reversal of that plan.

In Land of the Free, the poem becomes what MacLeish called a "sound track.” It employs the additive principle so that the reader seems to hear the thoughts of the people in the portraits. Other images also become winged, as, with a view across mountaintops: "We looked west from a rise and we saw forever.”

Dorothea Lange, who took most of the photographs used in Land of the Free, has, as the social scientist Paul Taylor, her husband and colleague, wrote, "an ear as good as her eye.” She listened to the actual words of the people she was photographing and put their speech beside their faces. This direct and deceptively simple technique is perhaps even more powerful in the early "job reports” she and Paul Taylor submitted to various government agencies than in their book, An American Exodus, (1939), where the typography and layout do not fully implement their intention. But here the Additive Caption rises to real dramatic stature. A worried young sharecropper looks at you . . . "The land’s just fit fer to hold the world together.” A gaunt woman, worn with work, smiles wryly as she clasps her head ... "If you die, you’re dead — that’s all.”

Barbara Morgan’s Summers Children, (1951), is the most imaginative integration of images, words and layout I have yet seen. Perhaps this is because it is, to its least detail, her own expression; she not only photographed, listened, wrote, and assembled her sequence — she also designed the format, the layout and the typography, even to setting the type herself. Each photograph has been cropped and sized until it is clear as a note in music in its relation to the spread and the sequence. Each spread expresses in its layout the dynamic tensions, rhythms or moods of its images. The text is handled with a freedom and a lack of formula unusual in photobooks. Here the additive principle is used as a thread of continuity, appearing or disappearing at need. A title may serve as a pivot for a spread, or as a launching-platform for several spreads. A phrase caught from the children’s speech suddenly evokes perspectives into our own memories. Many spreads convey their message through images only — and then there is a section where tiny images of children serve as visual gracenotes to their own songs, chants, and riddles.

The additive principle at this stage looks like a whole new medium in itself. Its potentials seem scarcely explored, like a continent descried from a ship.

To sum up this inquiry: a new language of images is apparently evolving, and with it a new use of words. There are now photographs complete without words as there have for thousands of years been books complete without pictures. Where the two mediums meet, they demand that each complement and complete each other so that they form one medium. They demand also that they shall be arranged so that their visual pattern is clear to the eye, or, when the words are spoken, that what is heard is timed and cadenced with what the eye sees. And we are only beginning. Photography is a young medium, and we who work in it are still pioneers.

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Nancy Newhall

-

Letters To The Editor

Letters To The EditorLetters To The Editor

Fall 1959 -

Foreword

Spring 1965 By Nancy Newhall -

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine Art

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine ArtI. Image In The Ground Glass

Spring 1975 By Nancy Newhall -

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine Art

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine ArtII. Mr. Robinson’s Tea Party

Spring 1975 By Nancy Newhall -

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine Art

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine ArtV. Rome And Reformation

Spring 1975 By Nancy Newhall -

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine Art

Part One P. H. Emerson: His Life And The Fight For Photography As A Fine ArtVIII. "A Reformer Needed"

Spring 1975 By Nancy Newhall